For the EPA, a Moment of Reckoning

In 2017, during an especially dark moment in the history of environmental regulation, Jill Lindsey Harrison embarked on a bold project: She began writing a book critical of the EPA. Is it fair to criticize the good guys when there’s no shortage of villains to expose? Absolutely, argues Harrison. Noble institutions aren’t impervious to faults. Uncovering the nature and extent of their dysfunction shouldn’t be seen as condemnation, but rather as a demonstration of support for their principles and an insistence they live up to them.

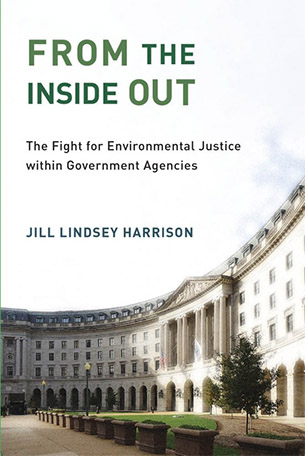

Drawing on more than 160 interviews, including dozens of conversations with current or former agency staff members and environmental justice activists, and more than 50 hours of participant observation of agency meetings (both open- and closed-door), “From the Inside Out” offers a unique account of how bureaucrats resist, undermine, and disparage environmental justice reform — and how environmental justice reformers within the agencies fight back by trying to change regulatory practice and culture from the inside out.

The Trump administration, whose attacks on environmental protections and other civil rights were devastating in scope and consequence, may be history, but Harrison reminds readers that even under the best of circumstances at the federal level — during the Obama administration, whose top leadership actively endorsed environmental justice (EJ), appointed high-level EJ staff, and assigned EJ training to all employees — EJ-supportive staff felt that their efforts were stymied by the ways some of their own colleagues responded to proposed reforms and treated EJ staff.

Criticism is not always well received and bureaucracies are not known for swift reforms. However, our conversation below reveals the power of candor and good faith when addressing difficult issues and trying to make real change.

Beth Clevenger: Some of your colleagues and allies expressed varying levels of surprise, admiration, and even trepidation when told you were writing a book critical of the EPA at a time when the agency was being dismantled and undermined by the Trump administration. Your frank response was that a crisis is not an excuse to abandon our principles, especially our commitments to equity and justice. What’s not revealed is the book’s origin story. How did you catch wind of the tension between Environmental Justice and the broader staff within the EPA, and at what point did you realize the scale and impact of the dysfunction?

Jill Lindsey Harrison: While other scholars have provided crucial insights into factors that undermine agencies’ EJ reforms, they give us very little insight into the experiences of those leading EJ reform efforts within the agencies. What do they feel are the primary constraints they face? I therefore designed this project to shine a light on what it’s like to work in support of environmental justice within these agencies that are such notoriously closed institutions. This requires talking to agencies’ EJ staff and observing them at work.

“Agency staff reject EJ reforms as conflicting with their ideas of ‘who we are’ and ‘what we do’ as a government agency. That is troubling.”

Because the work is so controversial, getting staff to be frank with me about conflicts they experience at work required that I assure them that I would not reveal their identities. In some of my earliest interviews with agency staff for this project, EJ staff made very clear that one of the primary barriers they face is pushback against EJ reforms by their own colleagues who see EJ principles as conflicting with their ideas of what it means to do good environmental regulatory work. That is, agency staff — who by all accounts largely identify as public servants and environmental stewards and could make much more money working in the private sector — reject EJ reforms as conflicting with their ideas of “who we are” and “what we do” as a government agency. That is troubling.

The diversity of thought about EJ within these agencies didn’t necessarily surprise me — I had observed and documented diversity of perspective among environmental regulatory agency staff in my first book, “Pesticide Drift and the Pursuit of Environmental Justice.” But what did surprise me was the pervasiveness and stridency of staff members’ resistance to EJ reforms, the fact that such resistance stems in part from popular and problematic colorblind ideas about what it means to be a fair or neutral public servant, and my growing understanding that agency staff could be doing much more to support EJ than they currently do, even with existing (and limited) resources, regulatory authority, and analytical tools. I knew I needed to document the forms and roots of that resistance to EJ reforms.

BC: As noted in the preface, “From the Inside Out” was written during a dark moment in the history of environmental regulation under the Trump administration. The preface also points out that regardless of who sits in the Oval Office, environmental justice has a history of being relegated to the shadows. On January 27th, the Biden-Harris Administration announced executive action that formalizes President Biden’s commitment to make EJ a part of the mission of every agency, not only the EPA. What do you think — will this time be different?

JLH: I certainly hope so. The Biden-Harris Administration’s investment into environmental justice is indisputably unprecedented, from executive orders, resources for EJ grants and programming, the new White House Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, political appointees with strong EJ track records, and more. But “From the Inside Out” shows that, ultimately, environmental justice will also require frank conversations within agencies about what it means to do good work and the need to center EJ principles in how we measure and assess the fairness and effectiveness of these agencies.

Movements for racial justice — and the massive protests in summer 2020 — have helped catalyze this work and brought considerable new attention to public institutions’ impacts on racial inequality and injustice. More and more agency staff are seeing the importance of EJ reforms and asking how they can help. This is so important. The question is: What will agencies do with all of this momentum of racial reckoning? Will agencies enact concrete reforms that will systematically improve material conditions in our nation’s most environmentally burdened and vulnerable communities, foster greater environmental equity across communities, and enable members of those communities to actually shape the regulatory decisions that so deeply affect their lives? Those are the key benchmarks of environmental justice — those are the metrics to which we need to hold agencies accountable.

BC: The executive order establishes a White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council and a White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. “From the Inside Out” claims that “to protect our most overburdened and vulnerable communities, we cannot restore our environmental regulatory system to its previous form.” So, the U.S. federal government is going to re-envision its agencies’ commitments and priorities. Now’s our chance. What recommendations would you lend the council members at this crucial moment of reform?

JLH: This council has a valuable opportunity to shape the ways this administration understands environmental justice. The council should elevate that environmental justice needs to be measured not only in terms of increasing public engagement but also in terms of substantially improved conditions in our nation’s most vulnerable and environmentally overburdened communities. The council should also emphasize that environmental justice requires cultural change within federal agencies — changing hearts and minds about the agency’s commitments – which agency leadership and management must foster through strongly endorsing environmental justice principles, requiring EJ trainings for all staff, and fostering dialogue about racial injustice and other elements of EJ. The council should also press the administration to institute concrete, structural changes to the ways nearly every member of federal environment-related agencies does their work.

These structural changes include conducting EJ analyses for all major permit reviews and reject permits that would worsen environmental conditions in the most overburdened communities; conducting EJ analyses for all major new rules and rule revisions and ensure that they improve environmental conditions in the most overburdened communities; focusing environmental enforcement resources on the most overburdened communities; prosecuting violators to the greatest extent possible under law; integrating EJ into all job description; devoting staff time to EJ reforms; holding all staff accountable for instituting EJ reforms; and publicly reporting on accomplishments and on areas needing improvement. That’s a lot. But it’s all within reach and so important. To facilitate this, agencies’ legal counsel should further clarify agencies’ regulatory authority to do these practices, and to further establish that authority, the council should emphasize the importance of legislation that would further authorize these practices (such as the Environmental Justice for All Act).

BC: How has the book been received by state and federal environmental staff? Any difficult or encouraging stories to relay?

JLH: The book is getting a lot of attention by state and federal agency staff. I am grateful for this, as I very much want them to read and discuss it. Many staff from different agencies have reached out to me about it, all saying that the book resonates with their experience, they are encouraging their colleagues to read it, and they are hopeful that things are changing given all of the racial reckoning their organizations are engaging in. It is gratifying to hear that I got the story right for so many folks, and also that more and more agency staff are expressing support for EJ. At the same time, it is difficult to hear about continuing ways that agency staff push back against proposed EJ reforms. In addition to these individual connections, I have been invited to give presentations to top agency leadership at numerous state and federal regulatory agencies in the past six months. I am heartened by their willingness to engage with these difficult findings, and to collectively think through what is needed to support environmental justice.

BC: Was anything — a quote from an interview, an observation, a radical proposition, personal commentary, anything large or small — left out of the book that you wish had been kept in? If so, do tell.

JLH: I had to omit a lot of detail about my research participants — their gender, race, ethnicity, Indigenous status, class, and more — so that they could not be identified by readers. Without doing so, most would not have been so frank and candid with me. But, as a result, some important nuance disappeared from view. One illustrative example that I kept in the book was a comment from Jim, a white, male, EJ-supportive staff person who said that he is taken more seriously than his Black colleague even when advocating for the same EJ reforms. This type of bias needs to be illuminated and grappled with, as does the importance of those with gender, racial, and other forms of privilege fighting for racial justice reforms. I would like to find a way to elucidate in more detail the ways that race, gender, class, and other forms of social status shape negotiations about social justice within these organizations.

“This moment of racial reckoning presents an incredible opportunity to create a world that is not only more sustainable but also more just.”

BC: Since the book was published, anti-racism and environmental youth movements have gained momentum and their principles have become prominent in the public discourse, sparking self-reflection and calls for systemic change. Central to these movements is the tenet that racism and environmental issues are not isolated issues; they manifest in all aspects of life. The isolation of EJ by environmental agencies staff is the root problem interviewees identified in the book. Might the messages and newfound prevalence of these social movements vindicate and empower the EJ staff and provide the much-needed push for cultural change within the agencies?

JLH: Absolutely. These social movements have indisputably forced government agencies, like so many other organizations, to confront and grapple with the ways they unwittingly contribute to racial injustice and environmental harm. Agencies’ EJ staff have never been busier or in higher demand. And yet the empirical question remains: What will come of all of this attention? To make good on their professed commitments to environmental and social justice, government agencies will need to change the ways all staff do their work – so that these agencies meaningfully improve environmental conditions in the communities of color, Indigenous communities, and working class communities that have been harmed the most. The reckoning is important – and it must lead to systematic, material change.

BC: 2020 was a momentous year. The COVID-19 pandemic, racist violence, and political upheaval left no one unaffected and the experiences have changed many people’s worldviews. What about yours — if you were to write a Coda to the book, what might it include?

JLH: I would want to honor the movements for social justice that have flourished in the past year and how much they have catalyzed. This moment of racial reckoning presents an incredible opportunity to create a world that is not only more sustainable but also more just. There is so much momentum and possibility right now. Let’s not squander it.

Beth Clevenger is an acquiring editor for the MIT Press.

Jill Lindsey Harrison is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is the author of “From the Inside Out: The Fight for Environmental Justice within Government Agencies.”