For Brilliant Color: Packaging the First LSD Blotter

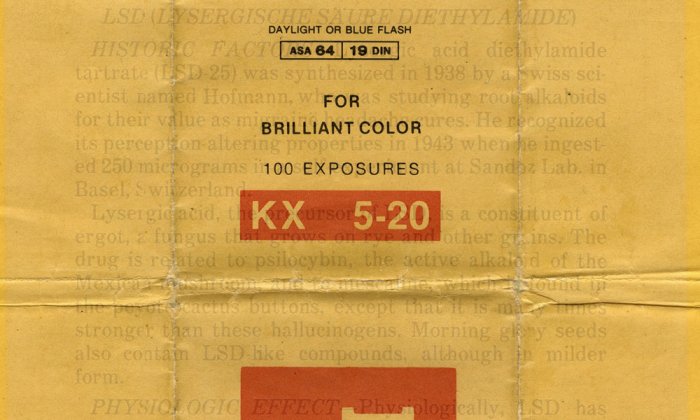

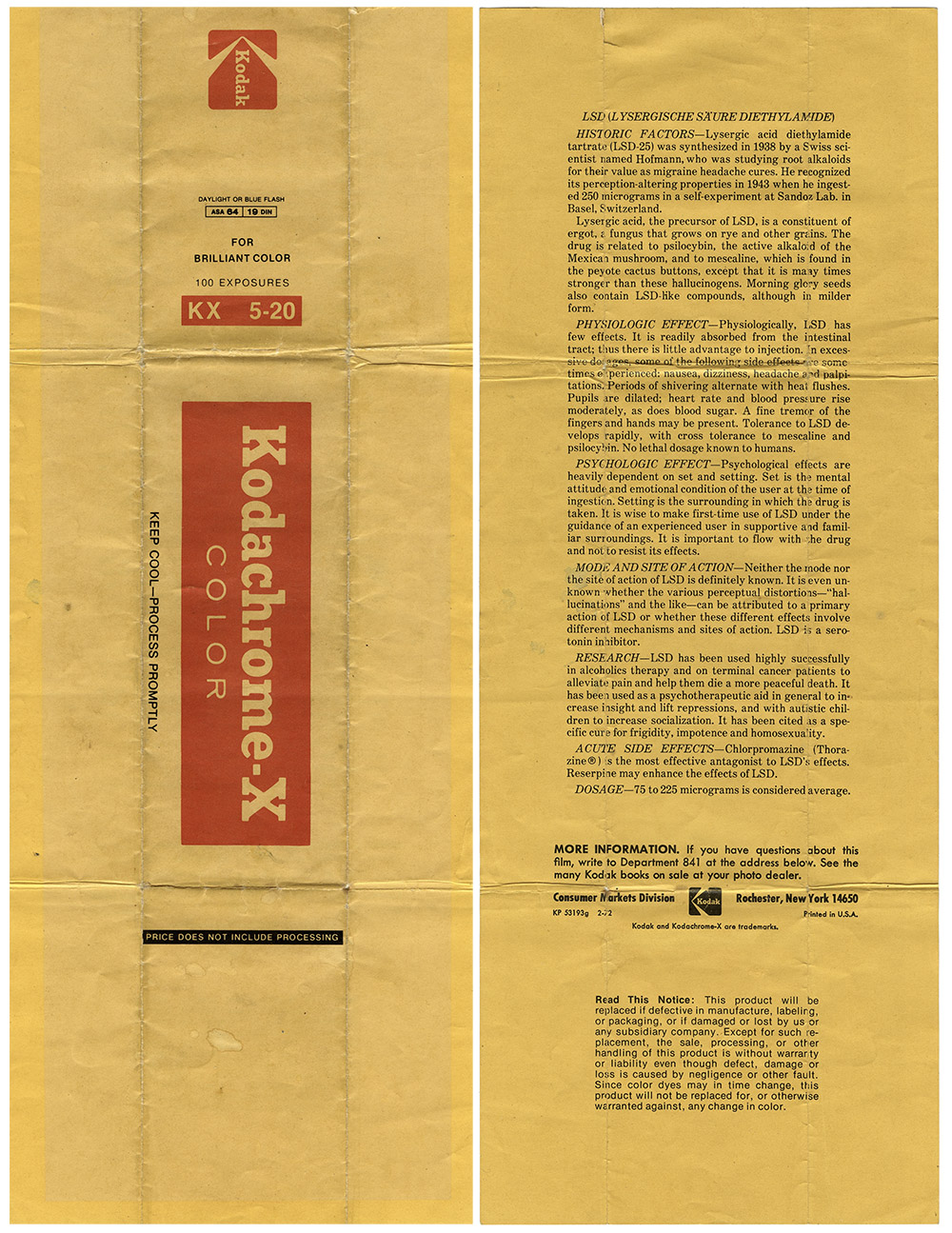

The image that follows is not of actual Kodak film but rather of a clever and gently satiric stealth packaging for underground LSD made by the New Yorker Eric Ghost — aka Eric Brown — in 1968. Ghost first took LSD in the Lower East Side around 1965, after a peripatetic life of military service, armed robbery, and prison. He swallowed nearly 4,000 micrograms, or mics, of pure Sandoz, smeared across a sugar cube, and the thermonuclear revelation occasioned by this enormous dose convinced him to co-found the Psychedelicatessen, a legendary though short-lived head shop that opened on 164 Avenue A in 1966. Like many acid people at the time, Ghost was messianic about the molecule and its potential to improve people and the world. Once LSD was banned, he decided to start cooking and distributing the material himself.

In contrast to today, when psychedelics are imagined to be medicines, party favors, or indigenous sacraments, many LSD users in the 1960s imagined their favorite substance as a kind of media. Like the increasingly technological media of the postwar world, LSD filters, transforms, and amplifies non-drug phenomena. Ghost played with this association by disguising his acid as film stock promising “brilliant color.” Each sheet was wrapped inside mylar, which not only protected the acid from damaging UV light, but also discouraged suspicious parties from opening the package on a whim, potentially destroying unexposed film. This “medium is the message” idea permeated acid discourse and marketing. Other examples include “Window pane,” “Clearlist,” and some of the first printed LSD blotters, which featured electric light bulbs.

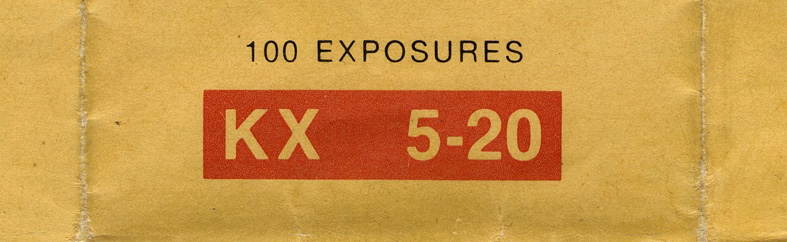

Ghost’s stealth packaging contained a novel and significant development in LSD distribution: the first mechanically produced examples of blotter paper dosed with drops of LSD. Liquid LSD had been placed on actual blotting paper and other paper products before, but these transfers would occur one drop at a time, using a pipette or eye-dropper. Ghost and a colleague accelerated this process by designing and building the Mark I, a device that allowed 100 pins to be dipped simultaneously into a pan of LSD in solution, and then moved as a single unit and impressed simultaneously onto a single absorbent piece of paper. The pins, and the dosed paper that resulted, followed a compact grid, which took the form of five tight rows of 20 columns each — the “5-20” pattern slyly referred to above. Each one of the Ghost’s drops contained a hefty 1,000 mics of LSD, which were left to the distributor or client to manually cut into four smaller hits, each packing a still solid 250 mic punch. This arrangement — the “four-way” — would recur throughout the history of blotter.

Opening Ghost’s package, purchasers would discover a handy information sheet that today gives us a sense of how some underground purveyors understood and promoted their wares. Rather than hippie mysticism or revolutionary cant, Ghost’s text presents LSD as a scientific product of a modern research lab run by a pharmaceutical corporation. Though LSD was related to an organic material — the ergot fungus on rye — part of the drug’s curious profile emerged from its origins at the heart of European technological modernity. Though some of Ghost’s information is off (LSD is not chemically similar to mescaline), it demonstrates the nerdy fascination that was always part of modern psychedelic culture.

The most dominant and consistent idea in postwar psychedelic culture and research, still widely used today, is the role of “set and setting” in influencing the experience. Though trumpeted by Timothy Leary and his co-authors in the 1964 book “The Psychedelic Experience,” the notion that LSD reflects and amplifies internal attitudes and environment cues had been recognized by researchers and users in the 1950s. This recursive effect helps explain the wide variety and plasticity of psychedelic effects, as well as the importance of the cultural stories that surround these compounds — expanded consciousness in the 1960s; cluster headaches and PTSD today. Even in those hedonistic and experimental eras, though, the important role of the guide was recognized.

Today’s clinical and therapeutic promoters of the “psychedelic renaissance” often present themselves as novel pioneers. Ghost’s text reminds us that the 1960s research community had already explored many clinical applications of LSD — for alcoholism, pain and anxiety among cancer patients, psychological repression, and even the challenges of autism. At the same time, the mention of LSD as a possible “cure” for homosexuality — something that was explored earlier in the 1960s by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, who later embraced his gay identity — reminds us of the distortion inherent in such research agendas, as well as LSD’s darker legacy as an agent of behavioral modification.

Erik Davis is a scholar, award-winning journalist, and speaker whose writing has ranged from rock criticism to media studies to creative explorations of esoteric mysticism. He is the author of, among other books, “High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies” and “Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium.”