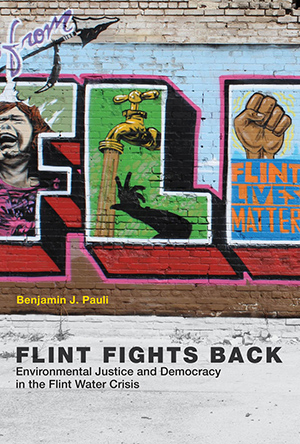

Flint Fights Back: In Conversation With Benjamin Pauli

When Benjamin Pauli moved to Flint, Michigan, for a teaching gig in 2015, he thought he knew what to expect. He was well aware of the discouraging statistics — among them, the high rates of violent crime and the astounding number of families living below the poverty line. He was only dimly aware, however, of another issue that was bubbling up, one that had not yet gained national attention. “When I turned on the bathtub faucet one evening to fill the bath for my son and brown, grainy water gushed out, I wrote it off as an anomaly,” he recounts in the introduction to “Flint Fights Back,” his powerful account of the Flint water crisis. “The resident voices pleading that the water was not safe were, from my perspective at the time, faint, drowned out by government authorities who said the water was fine and presumably knew what they were talking about.”

His new community, he found, was in a tense relationship with its government, stemming from water safety concerns that were hidden by their very own city representatives. Public organizers and protests gained momentum, and Pauli, animated by the upsurge of environmental activism, joined the Flint community’s fight for water rights and efficient democratic representation. His involvement allowed him to pinpoint numerous industrial and governmental actions that contributed to Flint’s water crisis, decisions that occurred behind bureaucratic red tape but came back to haunt citizens.

In an email exchange with the MIT Press Reader, Pauli discussed his relationship to the Flint water crisis and the ability of activism to inform — and transform — democratic institutions.

Zoe Kopp-Weber: In “Flint Fights Back,” you raise powerful questions about the intersection of knowledge and power: “Who decides what deserves to be known? Who decides who gets to know what is known, [and] who produces the knowledge that is known?” We’ve seen this struggle play out in Flint and also with the catastrophic BP oil spill. Besides obviously remedying the issue itself, how do you propose we bridge this knowledge/power gap?

Benjamin Pauli: I’m not sure that I see it as a “gap,” actually — rather, knowledge and power are intertwined in complex and not-always-obvious ways. What we call “knowledge” does not fall from the sky — it is a human product, and therefore it would be surprising if power dynamics didn’t play some role in how it was defined, created, and propagated. At the root of any truth-seeking enterprise are decisions about what questions deserve to be investigated, who gets to investigate them, how the resulting information is managed, interpreted, and communicated, and so forth. Not everyone has an equal amount of power over these kinds of decisions. That’s not necessarily a bad thing — as in the political sphere, we might decide that it is right or at least useful for some people to have more of this decision-making power (say, because they have more expertise, or more popular support, etc.). But just as we seek to ensure that political power is constrained and accountable, we should ensure the same is true of power in the realm of knowledge production and dissemination, especially when we presume to unite this kind of power with principles of social justice and enlist it in social struggle.

What we call “knowledge” does not fall from the sky — it is a human product, and therefore it would be surprising if power dynamics didn’t play some role in how it was defined, created, and propagated.

Z.K.W: In the preface, you explain that you initially didn’t register the resident voices that were saying the water in Flint wasn’t safe. You regretfully state that even despite your history of activism, it wasn’t until you received your own water test results and it became personal to you and your family that you started paying close attention and taking action. Did your neighbors, in what you acknowledge as a privileged, relatively affluent neighborhood, come to a similar realization or was this a point of tension once you joined the movement?

B.P.: In the summer of 2015, I was new to the community and in many respects still trying to get the lay of the land. There was no official “water crisis” yet, and I was oblivious at first to the activism that was going on. The way my family was affected personally by the water was one component of my awakening to the issue, but I wouldn’t say it was decisive. Like many other relatively privileged people, I have a sort of a knee-jerk tendency to think that things are probably not as bad as people say, and that everything will work out in the end, so even after our family experienced some problems I was slow to believe that the crisis was all that serious. It was more once I realized how important the issue was to the community as a whole that I decided to get involved. As for the perceptions of other residents in my part of the city, it’s important to remember that there was and still is a range of opinion in Flint about the severity of the crisis. I think some folks — a minority, to be sure — have always felt that the crisis was never much of a crisis at all, and certainly there are many who are eager to move on from all the talk about water and have been for some time. Whether those sentiments are more prevalent in neighborhoods like mine I can’t say with any certainty, but that is a common perception. Part of the challenge of doing this work has been navigating different subcommunities within the city and maintaining friendly relationships in all of them, which has indeed been a little tricky at times

Z.K.W: The water movement in Flint became as much about the denial of democracy as it was about environmental injustice. In the early stages of the crisis, how did you see Flint activism evolve from its beginning as a communal concern for residents’ well-being to the development of a new political consciousness?

B.P.: Because I was not living in Flint at the beginning of the crisis, I didn’t “see” it, but that theme emerged very clearly in my conversations and interviews with activists. In the book, I suggest that the water movement in Flint represented a fusion of a newly mobilized contingent of residents worried about water cost and quality with a “pro-democracy” stream of activists already experienced in political analysis. The concerns around democracy emphasized by the latter group, I think, helped residents to make connections between tangible experiences of contamination and harm and the more abstract and distant political institutions responsible for decision-making around water. Tracing the water crisis back to a crisis of democracy also encouraged a kind of structural thinking that linked originally isolated experiences back to the same system and, in so doing, fostered the development of a common identity and common struggle.

Z.K.W.: You describe your purchase of a lead filter which required replacing your kitchen faucet. This solution is one that you acknowledge many residents didn’t have the time or resources, to afford. In what other ways was class an issue during your involvement with the water movement?

B.P.: Residents have incurred numerous expenses during the crisis that some are better able to afford than others. Some of those expenses relate to filtration, some to bottled water, some to replacing appliances and pipes damaged by the water, some to medical bills, and others to factors we’re probably not even thinking about. I don’t think there’s any doubt that when everyday life is disrupted by environmental contamination, it is harder on poorer people. We should also remember that there are opportunity costs involved, too. It’s kind of painful to imagine all the things we could have been doing with our time and resources if we hadn’t spent the last five years worrying so much about water — and again, I think lost opportunity is probably most impactful on those who had fewer opportunities to begin with. So when we think about the effects of the crisis, I think it’s safe to say that class is a factor. Class has also been invoked by activists to explain why the crisis happened, or at least was allowed to go on for so long. For example, was Flint not worth “going out on a limb for” (as an EPA official infamously said) because it was a poor city? Finally, I’ve found that class is an important component of activist identities in Flint — partly because of the city’s proud history of organized labor, partly because of the feeling that shared class identity offers a useful basis for solidarity.

Class is an important component of activist identities in Flint — partly because of the city’s proud history of organized labor, partly because of the feeling that shared class identity offers a useful basis for solidarity.

Z.K.W.: There are narratives other than the “political” narrative of Flint’s water crisis, which you describe as the technical and historical narratives. So many different problems occurred to create this major issue that one can’t definitively point the finger at a single person or entity. What is your goal in activism when it is not as clear-cut as, say, firing a single official?

B.P.: When we approach the water crisis (or any similar crisis) as scholars, I think we have a certain duty to try and look at it in its totality. It is not enough to look at “technical” or “historical” or “political” factors separately — we have to take them all into consideration. This may lead us to conclude that the causes of the crisis are multifaceted and interconnected, with responsibility diffused in complex ways across a wide range of actors. Political accountability, however, often requires us to narrow our view to focus on particular people, institutions, and actions, so that we can decide who is most responsible and therefore most worthy of punishment or penitence of some kind. Should we point the finger, for example, principally at a few engineers making technical decisions, or should we point it at the architects of the political framework within which they were operating (or both)? The way we frame the crisis, and the story we tell about its origins and significance, will help to determine how we answer that kind of question, and I think social movements can play a significant role in shaping frames and narratives as part of the accountability work they do. Of course, activism has other roles to play, too — much of it in Flint has been focused on addressing immediate needs around the water, lifting up lingering resident concerns, and waging longer-term struggles for reparations and reconstruction.

Z.K.W.: In joining the Flint water movement, you used a sociological tactic known as “social shrinkage,” a technique implemented to minimize one’s difference in an unfamiliar social setting. Do you think increased application of this method could behoove scholars studying other movements?

B.P.: I took the term “social shrinkage” from Alice Goffman, a white, female sociologist who used the technique in studying the lives of mostly young black men in North Philadelphia. When you do ethnography, there is always the risk that your presence will alter the behavior of those you’re seeking to understand. “Shrinking” yourself so as to minimize whatever disruptions result from your presence is, I think, a useful strategy at the beginning of this kind of research because it makes it more likely that you’ll get an authentic sense of how the community under study operates. As explained in the book, minimizing myself at first was also a way of making it clear that I was not out to impose my own agenda on anybody and intended to respectfully follow the lead of other residents who were already mobilized. Gradually, I developed into more of a participant observer and became more visible within the activist community. But all along I have remained committed to letting others take the lead whenever possible and helping out where I can rather than initiating things. I think other researchers can find this tactic useful because it can help mitigate the power differential between academics and residents of marginalized communities, ensuring that the former stay in the back seat unless invited up front.

Z.K.W.: Do the recent no contest pleas by government officials provide any sort of healing for the community, or is it going to take substantial direct action for Flint’s government to regain the trust of its constituents?

B.P.: From the perspective of many residents I’ve spoken to, we are a ways from realizing “retributive” justice in the courts. You could say that the fact that so many people (fifteen total) were charged with crimes, all the way up to individuals in the governor’s cabinet, is in itself a kind of victory for accountability — it is certainly unusual, and regardless of the outcome of the cases it has brought many facts to light that probably would otherwise have remained obscure. But so far, we have had no trials (just preliminary hearings) and no convictions. One of the highest-profile defendants, former Director of the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Nick Lyon, will go to trial for a misdemeanor, but it’s possible that the most serious charges filed against him and other defendants will be thrown out during the appeals process. Furthermore, one often hears the sentiment around here that some weren’t charged who deserved to be — particularly former Governor Snyder. So while the charges themselves are notable, and in some ways unprecedented, I think the general feeling is that there hasn’t been much of a payoff yet. Certainly it will take a lot more to reestablish trust with residents.

UPDATE: Subsequent to the original version of this interview, the Michigan attorney general’s office made national headlines when it dismissed all outstanding criminal charges related to the water crisis, with the promise that it would conduct an even more thorough investigation and potentially re-charge some of the defendants. Pauli’s final answer has been updated below to reflect the Flint community’s reaction to this development.

My sense is that there is a good deal of concern and trepidation among residents afraid that this move is a prelude to dropping some, most, or even all of these cases entirely. Clearly the new attorney general and her team felt like they inherited a quagmire and wanted to press the reset button — in part because of new evidence that has come to light but also, I would guess, because they don’t believe some of these cases are winners, at least as presently constituted. Regardless of how one feels about any particular case, however, the (painfully slow) progress of the criminal cases in general was an important indicator for residents, I think, that some sort of retributive justice was in the works. Casting everything into limbo like this has, unfortunately, triggered longstanding fears of neglect and abandonment that one encounters regularly in Flint. A few people I’ve heard from are hopeful that this nuclear option will yield better results in the long run, but most are, I would say, cautiously pessimistic.

Zoe Kopp-Weber is a publicity intern at the MIT Press and a student in Emerson College’s Publishing and Writing program.