“I did it for the uplift of humanity and the Navy”: FDR's Gay Sex-Entrapment Sting

On March 16, 1919, 14 Navy recruits met secretly at the naval hospital in Newport, Rhode Island, anxiously awaiting instructions for their new assignment. The senior operatives explained that the volunteers were free to leave if they objected to this special mission: a covert operation to entrap homosexual men under the authority of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

By the end of the sting, investigators had apprehended more than 20 accused sailors and imprisoned them aboard a broken-down ship in Newport harbor. Anxious and afraid, the suspects remained in solitary confinement for nearly four months before they were officially charged with sodomy and “scandalous conduct.” The incident also foreshadowed laws and policies that the future President Roosevelt would put in place.

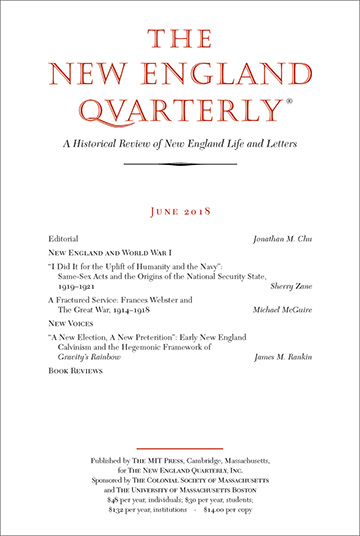

In this episode of the MIT Press podcast, podcaster Chris Gondek talks to Sherry Zane, the associate director of the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies program at the University of Connecticut, about her article, “‘I did It for The Uplift of Humanity and The Navy’: Same-Sex Acts and The Origins of The National Security State, 1919–1921,” published in the June 2018 issue of The New England Quarterly. A stream and transcript of the podcast, which was originally recorded in 2018, can be found below.

Chris Gondek: Hello and welcome to the MIT Press Journals podcast. I’m your host Chris Gondek. Today, I’m speaking with Sherry Zane, the author of, “I Did It for the Uplift of Humanity and the Navy: Same Sex Acts and the Origins of the National Security State, 1919 to 1921,” which was published in the June 2018 issue of The New England Quarterly. Dr. Sherry Zane is Associate Director of the Women’s, Gender, and sexuality Studies program at the university of Connecticut. Her current work focuses on how intersectional constructs of gender, sexuality, and race shaped national security concerns before the cold war. Stay tuned after the interview for more information about the show.

Sherry Zane, thanks for being on the MIT Press Journals podcast today.

Sherry Zane: Thank you very much for having me.

Chris Gondek: Now your article looks at investigations by the Navy of same-sex activity after the end of the First World War based around the mysterious section which is headed by then under-secretary of the Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Could you take us back to the time and explain why the Navy thought it was necessary to investigate these acts?

Sherry Zane: Sure. Let me start by giving some context of how this happens, because it’s one man that starts off the investigation, but there are already national concerns over moral corruption in society. There are a lot of anti-immigrant and anti-Bolshevik rhetoric that blames moral corruption on immigrants, African Americans, radicals, anarchists and women. It’s within this context of cleaning up moral corruption, this concern over what types of people corrupt society, that one man, a chief petty officer named Irvin Arnold — who is from Connecticut, but he was stationed in San Francisco — he comes to Newport in February of 1919, and he’s receiving some therapy at the Naval hospital there. He starts to witness some of the men who are patients putting on lipstick and makeup, other makeup powder puffs, wigs. And he starts asking them questions about their gender, about their sexual activity, and he’s keeping notes the whole time he’s in the hospital.

And then he decides that Newport is corrupt. Much like other people in the Navy are talking about the corruption of urban centers and port cities, there’s concern over the Navy being stationed in some of these port cities because of vice, drugs, prostitution.

“I think they should be investigated, let me do an informal inquiry, and then we should go to higher-up Naval officials.”

Irvin Arnold really takes it upon himself to initiate this first court of inquiry. He does so by going to the doctor at the Naval Hospital, Dr. Erastus Hudson, and tells him, “I think they should be investigated, let me do an informal inquiry, and then we should go to higher-up Naval officials,” which he does. In April of 1917, there were only 86,000 Naval personnel, and President Woodrow Wilson increases this number to almost 532,000 personnel in November of 1918.

Mothers, actually, during World War One are writing to President Wilson saying, “How are you going to protect our sons? They’re going to be exposed to all of these fights. They’re going to be exposed to drugs, and what are you going to do about it?” The Navy really joins in with other progressive era reformers, preventative societies, and anti-vice organizations to clean up these port cities where they’re going to be stationed.

As they begin to do that, they begin to get concerned about what type of men actually make up the Navy. After the war ends, you have a lot of the really experienced Naval personnel leave, and they have to bring in new personnel. They used this during World War One and after to think about, “How can we remake the American sailor?”

One of the things that they do is they start questioning not just what do they mean by physical fitness, but what do they mean by moral fitness, as well as using a Stanford-Binet IQ test, which is supposed to determine whether these men actually have good character, whether they have good morals. And they impose an Americanization of their forces as well, because they believe that if they make an effort to recruit white non-immigrant sailors from the heartland, from the Middle and the Middle West, this is going to help bolster their reputation.

So many white Americans feel that non-white immigrants and hyphenated Americans embodying these inherent elements of a criminal type, and are not going to be able to protect the country, or have an invested interest in protecting the country. And so they might be easily swayed to join forces in a campaign to destroy the country from within.

The Navy really takes on a lot of what these preventative societies and anti-vice organizations are already trying to do. And those reformers are made up of a white upper-middle-class group of people who are very concerned about stabilizing the traditional heteronormative American family structure. That’s why when Irvin Arnold comes in and he says, “This needs to be investigated,” there are already some systemic concerns over moral corruption in American society as a whole. And the Office of Naval Intelligence then agrees to go ahead with the inquiry, and then later on, about two months later, FDR gets involved.

Chris Gondek: It sounds like there’s almost the same kind of moral fervor that was going on at the same time regarding moving into prohibition. And it’s the same basic rough theory, but I’m hearing like the same kind of progressive ideals about, this is how we can clean up America. It seems like the same energy was kind of going on there.

Sherry Zane: Yes, absolutely. I think so. I think one of the things that the secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels does is he’s very committed to no alcohol in the officer’s quarters. And this is a big disruption in many of this… Many of the officers are really upset by this. And there’s also some ongoing, I guess, contention between the civilian-led administrative offices of Daniels and FDR and the admirals who feel that the civilians don’t know what they’re doing.

But again, you’re right, it is the same thing. It’s the anti-prostitution campaigns, the temperance movement. You also have concerns over women who want the vote, the suffrage movement. These are all disrupting more traditional American values. And that the men who are supposed to protect the country are going to be exposed to these things. And so if we want them to protect the country, then we need to protect them.

Chris Gondek: So in order to do this investigation, the Navy needed to recruit people to investigate the same-sex sailors. Could you talk about how they went about recruiting agents and what exactly what these agents expected to do?

Sherry Zane: Sure. So Irvin Arnold begins the initial recruiting in March of 1919. And he States in his later testimony when he’s asked this exact question, how did you recruit people? So he says that what he was looking for was men of good character and good looks. And he put a lot of emphasis on physical appearance. He said they must be honest, reliable, faithful, young, good looking. And the reason he keeps emphasizing good-looking is that he says that they need to be men between the ages of 19 and 24, because so-called perverts are not going to be interested in men over the age of 30 because by the time you’re 30, you lose your good looks.

So the age range of men that he recruits, he has 14 men that he recruits in March of 1919. And there are about… In the end, Arnold’s the oldest. He’s 41 years old, but 10 of the men are between 16 and 19 years old and the rest of the men are between the ages of 21 and 32.

So he also suggested that it would be best if they were not trained because they would get better results without training. So initially, he asked these first 14 that he recruits to meet him in the basement of the Naval hospital at the Newport Training Station, it’s in the x-ray room. And it’s all very secretive and they come into the room and Arnold begins by saying, “You’re free to leave at any time. There’s not going to be any retaliation if you choose not to do this special assignment.” And then he hands them a 14-point document. And the 14-point document says a variety of things. In the beginning it says that they are supposed to investigate moral corruption in the city of Newport, Rhode Island, and they’re looking for drugs, they’re looking for alcohol, they’re looking for female sex workers, and they’re also looking for men who engage in same-sex acts with other men. But most of the attention is put upon the idea that these men have to allow themselves to be solicited by other men. And the way in which they do this, he suggested in the document is that they have to be jolly, they have to be good-natured, they have to make dates with them, and they have to allow themselves to be solicited.

So nowhere in the document does it say what acts, what sex acts the men have to engage in. But through the conversations that the men have in that meeting and then later with FDR and then in the testimony done by the Senate subcommittee investigators, it comes out that there were discussions, and the men were told that they should individually decide which sex acts they wanted to engage in or they needed to engage in to be able to convict these men and incarcerate them. So each man was supposed to make his own determination.

And at one point FDR did contact an attorney to make sure that the men would be protected if they engaged in sex, same-sex acts. And the attorney suggested that they would be safe because they were engaging in so-called criminal behavior in order to catch criminals, and so that was okay.

Chris Gondek: So that’s how the men were recruited. What happened to men who were charged with the crimes?

When the Senate subcommittee investigates, they hold FDR morally responsible for the investigation and say that he should never hold public office again. And this is in 1921.

Sherry Zane: The men who were charged with the crimes were rounded up and imprisoned on an old broken down ship in Newport, the USS boxer. And they were held there for longer than they should have been without criminal charges. So what they did was, Arnold and his men took an ambulance and they raced around Newport one evening and just gathered up all these men, brought them onto the USS boxer, and then interrogated them through the use of third-degree methods. And the third-degree methods were questioning them for hours on end without food and water, sometimes using physical violence. And then after that, there were several complaints by people in Newport who heard that these men were imprisoned on this ship and many family members of the men who were entrapped and then imprisoned. And they were writing letters to the Navy office.

And what happened is, they were brought up on general courts marshals and each man after about, I think it took them more than 120 days to finally bring them up to a general court-martial hearing. One man ended up deserted, five were acquitted and 14 of the men were sentenced to between 20- and 30-year sentences for anal penetration and oral sex.

Chris Gondek: So what happened to the people in the Navy who are involved with this? Both Arnold and then other people further up the chain who approved this? Was this investigation when all was said and done considered a positive thing for the Navy or was it controversial even at the time?

Sherry Zane: It was controversial at the time because of the methods and because they used volunteer sailors. So in the end, what happens is, once the Senate subcommittee gets wind of this, because the Providence journal editor, John Rathom, is really taking FDR and Daniels to task in the paper. He’s exposing all of this. And he certainly has an ax to grind with FDR. So it’s not necessarily that they shouldn’t be investigated, but it was using what they called innocent boys to investigate it and allow themselves to be contaminated by engaging in these acts, that if you want to investigate so-called perversion, then you should use trained detectives to do so instead.

And so when the Senate subcommittee investigates, they end up blaming FDR mostly. They hold him morally responsible for the investigation and they say that he should never hold public office again. And this is in 1921.

So the operatives are honorably discharged. Nothing happens to them. The entrapped men are released from prison between 1921 and 1922 but they’re dishonorably discharged. So this follows them for the rest of their lives. They can’t get any military benefits, they can’t have a military funeral. And many of them, through tracing them through their personnel files, at different times, like 10, 20 years later, they contacted the department of veterans affairs to find out if someone was going to do a background check on them for a new job, would they find out. And they wouldn’t find out if the men… There were a couple of men that were acquitted so they were fine. But if the men were dishonorably discharged, they would have gotten this report from the Navy.

I think that clearly his privilege allowed him to whitewash his involvement, and the accused men can’t even get a military funeral 40 years later.

And FDR in the end, he’s morally responsible, but all know that he goes on to become the president of the United States. So he escapes any real consequence in the end.

Chris Gondek: Did he ever revisit the decision publicly years later or was it just like, this is something where he said, “This was a close run thing. I don’t need the center brought up. Let’s never talk about it again,” and just swept it under the rug.

Sherry Zane: He had to visit it again because he was concerned in his later gubernatorial and presidential campaigns, prior to that, he was running for the vice presidency under Cox in 1920. And people were questioning his manliness based on his moral character in the 1920s, but because Rathom — John Rathom, the Providence journal editor, John Rathom — dies in 1923, and the Navy wants to forget about the whole thing. So there’s really no one to challenge FDR after John dies. However, when he contracts polio in the summer of 1921, right after he has to give testimony to the Senate subcommittee, he contracts polio that summer. Questions about FDRs manliness are associated with his disability. And so he’s concerned about that when he’s running for the presidency. And in 1931, he accepts a challenge by a Republican writer Earl Looker to have a committee of respected physicians selected by the New York Academy of Medicine, examine him to see if he is competent enough to withstand these duties.

So Looker prints in Liberty magazine, that as far as he could see, FDR could take more punishment than many men 10 years younger. And as more magazines and books start to focus on him in 31, Looker contributes to a biography called “This Man Roosevelt.” Half the pages of the biography are devoted to his time as assistant secretary of the Navy, with the intent to whitewash FDRs reputation with respect to Newport.

So it’s just interesting because FDRs whole history, like he’s writing a biography of him, and half of it is devoted to the issue of Newport and proving that FDR had nothing to do with this. All he did was sign documents.

So I think that clearly his privilege allowed him to whitewash his involvement, and the accused men can’t even get a military funeral 40 years later. But he did have to revisit it. But I don’t think it ever came up, as far as I can tell during his presidency.