Epigenetics and Speculative Research: In Conversation With Larissa Sansour

The premise of Larissa Sansour’s post-apocalyptic film “In Vitro” is simple and yet wholly original. It involves two people — one having seen the world before an apocalypse, while the other having been born in its wake — in dialogue with one another about the inherited nature of trauma. This conversation takes place in a bunker underneath the town that the younger of the two is destined to rebuild, but has never experienced firsthand. Like Sansour’s other work, the film — part of a larger installation called “Heirloom” that was presented at the Venice Biennale in 2019 — explores themes of collective and personal loss, cultural erasure, and the effects of trauma on the national psyche. In sum, it’s a multifaceted and extensively researched project that unfolds across different time zones and discrete spaces.

It was with this often eclipsed level of research in mind that I began to develop Research/Practice, a series of books that explores artists’ materials and their approaches to developing projects. One of the first volumes in the series is dedicated to “Heirloom” and the specific practices that went into its development over an extended period of time. On the surface, Sansour’s methodologies appear to be informal, but they prove to be more structured than that, focusing as they do on multidisciplinary approaches (with people from different disciplines working together), interdisciplinary approaches (where knowledge and methods from different disciplines are integrated), and transdisciplinary approaches (where you get a unity of frameworks beyond the disciplinary perspectives).

I spoke with Larissa about the research elements that went into “In Vitro,” the allure of sci-fi, what it means to grapple with complex issues of national representation, and how epigenetics, or inherited trauma, can be used as a tool to shape the future in the image of the past. A longer version of the conversation featured below can be found in “Heirloom.”

Anthony Downey: This has been a long-term project in terms of its gestation period. Can you talk a little about how the idea came about in the first place?

Larissa Sansour: Yes, although the works for “Heirloom” were produced on relatively short notice—in eight months total—the research and conceptual framework was established before I was appointed by the Danish Arts Foundation to represent Denmark at the Venice Biennale. It usually takes me about two years to complete a project of this magnitude, and luckily I was already in early development on a feature film when I was appointed. All basic research had been completed, and my artistic collaborator, Søren Lind, had written several drafts of the manuscript. As the deadline for Venice was so short, we decided to keep the existing conceptual framework and scale the increasingly plot-driven script back to its origins as a short art film, identify the core philosophical argument, and experiment formally in ways that aren’t possible with the feature-length format.

Set in Bethlehem, In Vitro is a postapocalyptic film that takes place thirty years after an eco-disaster. In previous projects, I had been using science fiction to explore the concepts of collective and personal loss, cultural erasure, and the effects of trauma on the national psyche. The conceptual framework for the feature continued this line of research by accelerating the climate dystopia we are all currently facing, with a focus on the local factors further aggravating the ecological crisis in a Palestinian context. As we started editing the script down for the film, it became clear that the most crucial aspects to explore were the psychological implications of this potentially complete erasure, a tabula rasa. What is left when everything vanishes? What part of the past do we rely on for survival? So the script for In Vitro was written as a dialogue between two scientists, a generation apart: one having seen the world before the apocalypse and the other being born in a bunker underneath the town she’s destined to rebuild, but that she’s never experienced firsthand. So the climate disaster eventually became a pretext for a debate about the effects of memory, nostalgia, and inherited trauma on personal and collective identity.

AD: Could you talk more about the role of your research into sci-fi tropes and how it works as a conceptual gambit—how it allows you to do things that relate to both historical speculation and historical fact. There is also an impending sense of catastrophe (imminent and past) in science fiction as a genre, specifically around ecological disaster.

LS: For me, the allure of sci-fi is to be able to talk about the present without being dictated by the current political jargon. By getting rid of the present-day context, the past and its consequences can be reframed. This is particularly helpful when dealing with the Palestinian question, I think. The distance provided by the imagined future grants an immediate and quite liberating perspective. It gives me the chance to single out neglected or overlooked details, enlarge them, and emphasize their importance. I can treat these details in as much of a vacuum as they deserve, cleanse them of their current meaning, so to speak. And I guess the ambition is to refine them and eventually return them to their present context, hoping they will add new meaning.

With no viable present to speak of, the Palestinian psyche is suspended between the traumas of the past shaping the ambitions for the future.

Sci-fi also lends itself well to the Palestinian situation in terms of modes of temporality. With no viable present to speak of, the Palestinian psyche is suspended between the traumas of the past shaping the ambitions for the future. This suspension is key to In Vitro’s dialogue.

While the older scientist, Dunia, hopes to shape the future in the image of the past and relies on her memories and nostalgia, the younger scientist, Alia, rebels against this thought, suggesting that the very idea is flawed and relies on, as she says, a history reduced to reductive symbols and iconography, a future built on nostalgia.

As for the eco-disaster aspect, sci-fi frequently turns to apocalyptic tropes to facilitate the clean slate, the tabula rasa, which clears the way for new structures and systems to emerge. Climate change presents the most imminent threat to our civilization at this point, and that makes the setting relatable, which is why it is important for the world-building element of sci-fi not to appear too farfetched and get in the way of the conceptual reworking I set out to accomplish.

AD: You spoke earlier of the main body of research that precedes this project: Could you expand on that? I am particularly interested in the science of epigenetics and how it differs from genetics. How do such ideas inform your understanding of historical trauma?

LS: Epigenetics studies genetic inheritance not associated with alterations in the DNA sequence, meaning changes passed on genetically through generations in addition to what is delivered by DNA. One item that epigeneticists are studying as potentially inheritable is trauma. So although trauma has no impact on the DNA sequence, it can still be passed on genetically, meaning that children born of parents having experienced significant trauma could themselves carry this trauma. I find this fact particularly interesting in a Palestinian context. One thing is the narrative of trauma and the natural impact of such a narrative on future generations.

This makes trauma a psychological factor. But if trauma is passed on genetically, it is present from birth. In “Heirloom,” this inescapability of trauma is taken one step further, now not only limited to trauma itself, but the burden of a troubled history in a wider sense. What is usually seen as nurture in terms of oral delivery of a historical narrative in a specific cultural or national context is now genetically manifest. In the film this is, of course, a sci-fi twist on advanced scientific research, and it is implemented in the film as a means to present history as a genetically inescapable circumstance. If the total sum of your ancestors’ accomplishments, traumas, ambitions, errors, and experiences is already with you from birth, what are the options for breaking away from this heritage and carving out a new direction? It’s the classic battle between determinism and free will played out in genetic terms, and it further accentuates the obstacles for the younger generations in their attempts to forge a better future.

If the total sum of your ancestors’ accomplishments, traumas, ambitions, errors, and experiences is already with you from birth, what are the options for breaking away from this heritage and carving out a new direction?

AD: Do you see epigenetics as a potential tool in forging precisely that future, or does it suggest a degree of fatalism?

LS: I’m certain that the potential of epigenetics will have far-reaching consequences, but I am as of yet not aware of the scope of the discipline’s ability to forge actual futures. Engineering genetic heritage to not only pass on trauma but also memories is something I utilize in In Vitro. In a crucial part of the film’s fiction, epigenetics is used as a tool to shape the future in the image of the past. It is a rational attempt to preserve what is worth preserving and to prevent repetition of past mistakes. Dunia argues that no viable future is possible without an intact past as its foundation. The entire argument unfolding between her and her younger successor revolves around this issue. While insisting on the importance of the past, Dunia also refutes all claims of fatalism by suggesting that it’s not only a matter of restoring what was lost, but also a case of rectifying past errors. Alia disagrees. She finds this historical baggage a deterministic hindrance for shaping a new and more fertile future.

AD: Could you describe the other elements of research that went into “Heirloom,” not just the epigenetic elements but the literary, historical, and filmic elements too?

LS: As is the case with most of my projects, “Heirloom” is part of a continuum of research accumulated and partially explored in previous works. Specifically, my focus is on the interplay between history, documentary, myth, and fiction, and has been evolving throughout the past decade and the three sci-fi films preceding In Vitro. National identity, historical, nationalist, and colonial narratives, nation-building, regional symbolism, and iconography have all played a major part in my work. The research going into these topics over the years is multifaceted, with the extensive syllabus counting key works by historians like Ilan Pappé’s The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (2013) and the more discipline-specific Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (2001) by Nadia Abu El-Haj. On a related note, I have always been very interested in the academic research and writing on my own and related practices, as the academic treatment of the topics at stake often uncovers new and exciting aspects and helps me crystallize evolving ideas for future projects. Chrisoula Lionis’s brilliant book Laughter in Occupied Palestine: Comedy and Identity in Art and Film (2016), for instance, inspired some of the ideas for the In Vitro script.

I have always been very interested in the academic research and writing on my own and related practices, as the academic treatment of the topics at stake often uncovers new and exciting aspects and helps me crystallize evolving ideas for future projects.

I was never really interested in science fiction in my younger years, so my transition into it came with a steep learning curve based on literary sci-fi classics by authors like J. G. Ballard, William Gibson, and China Miéville, and more recent books like Don DeLillo’s Zero K (2016), as well as a wide selection of films like Blade Runner (1982), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Solaris (1972), to more recent films such as Ex Machina (2014), as well as the increasing use of sci-fi in the art world, as seen in Afrofuturism and more recent productions. In terms of film directors, the influence of Stanley Kubrick always finds its way into my projects, whether I intend it to or not. His one-point perspective has inspired my own image composition, just as I often end up referencing one or more of his most iconic scenes in my own films, like the twin girls from The Shining (1980). But the two main cinematic inspirations were always Andrei Tarkovsky and Ingmar Bergman, most notably Stalker (1979) and The Mirror (1975) by the former and Persona (1966) by the latter. I am particularly intrigued by the intensity of the dialogue between the two main characters in Persona, and the suggestive imagery in The Mirror, the nostalgic scenes in the summerhouse and the burning flames in the middle of the forest.

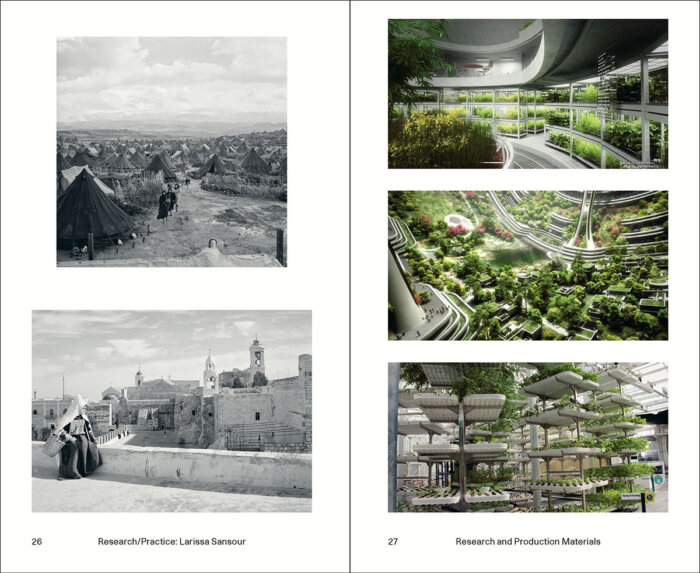

Talking more specifically about “Heirloom,” the first thing we developed was the narrative framework for In Vitro. The apocalyptic setting of the film took its initial cue from the looming climate catastrophe and its regional implications for Palestinian agriculture. Early research into preservation of native crops and heirloom seeds was followed by an interest in contemporary practices like aquaponics. This in turn led to the shaping of In Vitro’s underground orchard where high-tech botanists work to keep the regional vegetation alive for future replanting of the soil above ground.

The first thing we developed was the narrative framework for In Vitro. The apocalyptic setting of the film took its initial cue from the looming climate catastrophe and its regional implications for Palestinian agriculture.

Soon, the focus shifted from the apocalyptic foundations to the question of the psychological, political, and social implications of a people having undergone an all-erasing trauma. I then became interested in the nature of personal and collective memory along with an increasing fascination with the idea of inherited trauma, which led us to recent discoveries in epigenetics. While trying to get all of these topics and ideas to make sense as a manuscript, there were multiple research detours as well, at some point trying to understand the concepts of nothingness, voids, and absences through the properties of black holes.

AD: Could you talk about the production research; your trip to Bethlehem, for example?

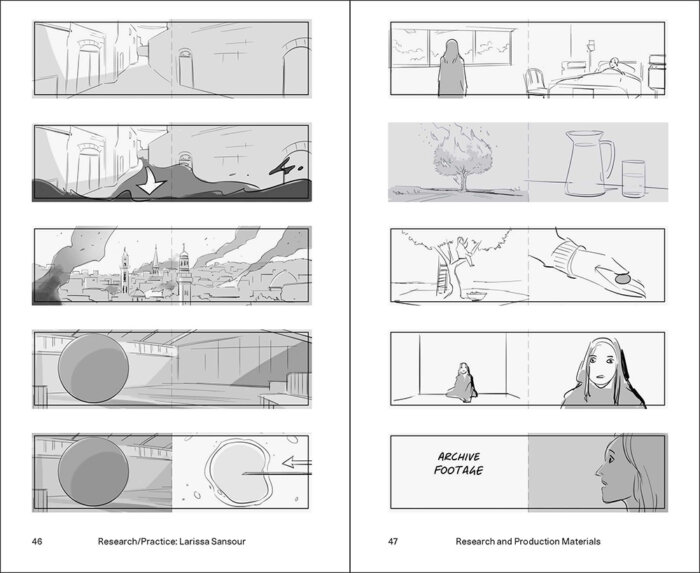

LS: The preproduction stage of the film was very condensed and comprehensive. During the few months available to us before going into production, we had to formulate the overall aesthetics, which had implications for our choice of shooting locations, costumes, set design, and director of photography.

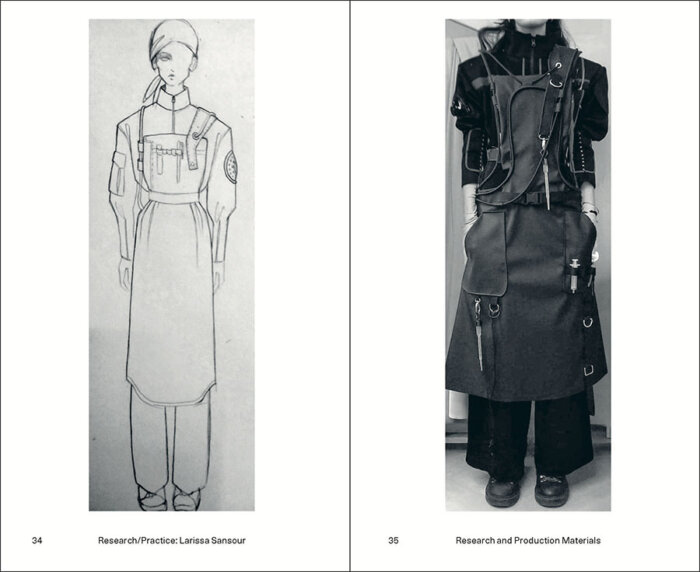

We explored a lot of different options for the costumes, from contemporary avant-garde designers with a postapocalyptic edge to steampunk and historical sci-fi designs. Since In Vitro consciously blurs temporalities, and sci-fi has a tendency to stop looking like sci-fi if you deviate too much from a retro-futuristic approach, we decided to appropriate design trends from the 1960s and ’70s, not only in terms of costume, but also hospital equipment and furniture design. For the underground compound, we landed on a Brutalist approach and spent a long time location-scouting, first online and then on actual recces to potential shooting locations. We went through a lot of Brutalist building options for the main location, but ended up choosing this amazing pyramid-shaped former art gallery at an abandoned boarding school in Oxfordshire. The place was vacated twenty years ago and looks completely postapocalyptic, with an empty indoor swimming pool, paint peeling off the pipes everywhere, and then this highly photogenic pyramid that we knew would make the perfect setting for In Vitro.

An early recce to Bethlehem with our director of photography and visual-effects (VFX) supervisor was also carried out. This was a crucial step because we needed to determine shooting locations and accessibility for camera crew, dolly tracks, and equipment, and our VFX supervisor had to map out the problems of each shot to determine the clean-up work needed in postproduction. Another vital task carried out in Bethlehem was the casting of the film’s young girl, who had to be local in order to avoid any logistical issues during the filming. We interviewed about ten girls, all extremely sweet and nice, but lacking in acting experience. On the final day in Bethlehem, we came across this young girl, Mimi, who had a passion for acting and her own YouTube channel. She blew us away immediately.

Developing sketches and approaches to the special effects was also an intense focus. We sat through endless simulations of liquid and researched 3-D explosions, fires, flames, insect plagues, draughts, DNA strings, egg cells, and other material for potential inclusion in the final edit. Another very interesting but time-consuming area of research was sorting through historical footage for the film in the archives of Imperial War Museum, British Pathé, and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency.

A crucial aspect of preproduction was the casting process. With two actors already in mind from the early stages of the script, we still sat through a lot of recent Palestinian and Arabic films to get a full picture of available talent. Listing multiple candidates along the way, we still ended up with our original selection, Hiam Abbass and Maisa Abd Elhadi, and fortunately they both agreed to participate. Once we had contracted them, we watched a lot of their previous performances to better identify which of their strengths to play to in the filming process.

While working on other aspects of the production and postproduction, including music composition and development of an overall sound approach and editing style, we were also involved in the production of the exhibition’s two other elements, namely, the hand-painted tiles from the tile maker in Nablus in the West Bank and the large-scale sculpture developed by the art production company Factum Arte in Madrid, with the latter element requiring significant research into sculptural materials, manufacturing processes, and, most importantly, the light-absorbing black paint to be applied to the sculptural surface to simulate a loss of its three-dimensionality. Further areas of research for the sculptural installation included cement-flooring options, casting procedures, tile laying, and lighting options. Overall, the short production period meant that there were many parallel dialogues and research efforts going on at the same time, but luckily I had a very solid core team to assist me throughout the process.

AD: Is a research-based methodology always relevant to your practice? I am particularly interested in the methodologies employed by artists. They tend, on the surface at least, to appear to be informal, but I think they are more structured than that, focusing as they do on multidisciplinary approaches (with people from different disciplines working together), interdisciplinary approaches (where knowledge and methods from different disciplines are integrated), and transdisciplinary approaches (where you get a unity of frameworks beyond the disciplinary perspectives). Do any of these define particular approaches in your work?

LS: It is probably a combination of them all. Despite merging film, sculpture, music compositions, installation, and architectural intervention, “Heirloom” sits quite comfortably within a contemporary art practice. Over the years I have gathered a core team of specialists from various disciplines: producers, VFX experts, composers, designers, and so on. I recently worked with an antique clock restorer, Julius Schoonhoven, who helped me devise a locking mechanism for a series of bronze sculptures, and I was very impressed by his skills. His workshop was full of old clocks, and while we were working together, he was also casting the missing pieces for the intricate clockwork in an eighteenth-century clock. It was very inspiring. The special-effects supervisor I work with on my films, Henrik Bach Christensen, has abilities reaching far beyond VFX, including 3-D modeling and printing. He’s a jack-of-all-trades and a tremendous resource. Like Søren, he has a background in philosophy, which also makes him a great partner for the conceptual aspects of the work we do. I also find it very inspiring to work with composers, and that feeling tends to be mutual because working with a visual artist often poses new challenges and gives them a freedom they are not used to when composing for theater or mainstream film. I’ve often worked with Iraqi electronica musician Aida Nadeem, and for “Heirloom” I teamed up with the Danish composer Niklas Schak, who does a lot of film and theater compositions. He searched long and wide for the right instrument to use for the film and the sculptural installation and finally found the amazing Cristal Baschet, a very distinct and bizarre wind instrument that has a deep trombone-like sound and was developed a half century ago by two French brothers. Schak played the instrument in a Paris sound studio and got the recordings he needed to compose the score for the film and the sound piece for the sculpture.

Despite merging film, sculpture, music compositions, installation, and architectural intervention, “Heirloom” sits quite comfortably within a contemporary art practice.

This gives me the freedom to conceptualize a project without the fear that it can’t be realized. I always have someone to go to for implementation, and it is always very inspiring for me to work with highly trained specialists in fields I personally have no practical skills in, like VFX, for instance, although I am getting more of an understanding of its possibilities and limitations, with the latter more often than not being financial.

Not only do I learn a lot from these people. Having access to their knowledge and insight also lets new ideas wander and develop more freely, as I don’t have to worry about transitioning them from idea to actual work. In that way, it’s sometimes a blessing not to know what can and cannot be done. I get to ask silly questions and suggest new ideas without knowing about the practical constraints, but somehow there’s always a solution. For “Heirloom,” for instance, we were inspired by Nessa Carey’s introduction to epigenetics, The Epigenetics Revolution (2012), and asked Bach Christensen for a very abstract visual representation of genetic material, which would also merge with the overall aesthetics of the film, and he came up with this amazing black-and-white DNA string gently twisting its way through dense liquid. It’s a really nice shot.

AD: There is also a level of serendipity involved in the research, isn’t there?

LS: Yes, of course. “Heirloom” was a major group effort with approximately 120 people contributing at various stages of the production, and this is not even counting all those involved in the formative stages. These are not always scheduled or targeted conversations, but often occur when I least expect it. When working on the early draft for In Vitro, for instance, a person introduced herself to me at a party and said that she had previously auditioned for a role in one of my films, so she wanted to offer her help for any future projects. I said that right now we weren’t looking for actors, but were in desperate need of a geneticist. She asked me if this was a joke, because she just happened to be a geneticist herself! Our conversation that afternoon led to new discoveries, specifically the idea of genetically inherited trauma, which is now key to In Vitro’s storyline.

Before that, the film project found its conceptual footing as part of a research collaboration with the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library. I was very interested in the impact of occupation on Palestinian agriculture and teamed up with my cousin Vivien Sansour, who does amazing work in Palestine and abroad with preservation of heirloom seeds. The vanishing of original Palestinian crops helped shape the overall approach to the kind of climate apocalypse I wanted to address in In Vitro, and it also defined the development of the film’s underground orchard. This line of research continued deep into postproduction of the film, as the design of the underground orchard relied on local crops, plants, and flowers, so I was in extensive botanical dialogue with our VFX team throughout that period.

The writing of the script also involved a lot of unexpected areas of research and interdisciplinary dialogues. Søren and I are both involved in the research and conceptualization stages. He then writes a first draft while I visualize the ideas, and that process is repeated until we’re both satisfied. Søren has a background in philosophy of the mind, and often revisits old philosophical texts or explores new ones in the process. For In Vitro, he spent a long time exploring memory and trauma, just as he got interested in philosophical, psychological, and astronomical approaches to the concepts of void, nothingness, and time. Sometimes a week of research ends up producing a single line of dialogue, while other times the tiniest of insights can suddenly inspire entire chapters. All of this accumulated knowledge stays with me and invariably forms the foundation for future projects. Epigenetics being one of the topics In Vitro generated an interest in, I am now involved in a new project continuing that line of research.

AD: Can we talk more about that new project?

LS: Søren and I are in early stages of a sci-fi opera on epigenetics commissioned by two art institutions and scheduled to premiere in the UK in late 2020. The opera will be presented as a three-screen installation featuring a single aria on inherited trauma performed in Arabic by a renowned opera singer. Her performance will be accompanied by VFX visuals and manipulated archival footage from Palestine. I was always intrigued by the idea of making an opera, the pathos, drama, and poetry of it. The primary commissioner of this new piece was interested in creating a dialogue between artists and geneticists, which I found really inspiring and just the right setup for the opera project that I had been contemplating for so long. So we are currently trying to familiarize ourselves with opera as a discipline and trying to understand how best to convert the scientific research into an aria.

Larissa Sansour (b. 1973, East Jerusalem) is an award-winning artist who lives and works in London.

Anthony Downey is Professor of Visual Culture in the Middle East and North Africa, within the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media at Birmingham City University. He is the series editor for Research/Practice, published by Sternberg Press, and the author of several books on the politics of visual culture.