A Dark History of the World’s Smallest Island Nation

Lying between Australia and Hawaii, the island of Nauru is as far from Europe as any place on earth. It wasn’t until November 8, 1798, when a British ship called the Snow Hunter was passing en route to the China Seas, did any European record seeing the island. Hundreds of Nauruans canoed out to greet the sailors. The captain of the Snow Hunter, John Fearn, did not permit his men to disembark. Nor did any Nauruans venture aboard. Still, the welcome charmed Captain Fearn, as did the warm winds, the island’s green central plateau, the swaying palms, and the white-sand beaches — so much that he named it Pleasant Island.

The sight (and wafting stench) of the Snow Hunter’s motley crew must have come as quite a shock to the Nauruans. At the time, life on the small island was mostly peaceful and predictable. Tensions among Nauru’s 12 clans did run deep, and now and then disputes did turn deadly. Any year with light rainfall would cause great suffering too, as the island’s only surface water is a brackish and shallow lagoon. Still, for thousands of years, Nauruans had managed to live largely in balance with nature, isolated but self-sufficient, with societal acrimony more or less kept in check. Captain Fearn’s naming of the island for the English-speaking world did not upset this stability. But it was an omen of dark times ahead.

Murder and Mayhem

William Harris touched ground in Nauru in 1842, after escaping from Norfolk Island, a British penal colony about 900 miles east of Australia. He did not go there in search of pearls or diamonds or gold. Nor was he looking to trade spices or log sandalwood. He went to live a carefree and easygoing life as a beachcomber, one of many convicts and deserters then hiding out in the South Pacific. The first beachcombers had come to Nauru in the early 1830s; for them, life was not as happy-go-lucky as they were likely imagining. During the 1830s John Jones, like Harris a fugitive from Norfolk Island, had ruled the Nauruan beaches with brutality, murdering at least a dozen beachcombers. Jones stayed on the edges of Nauruan society, brokering deals with passing ships to trade pigs and coconuts for tobacco, liquor, and rifles. Eventually, however, Jones fell out with the Nauruan chiefs (after he blamed them for his murders), and in 1841 they exiled him to Banaba, a neighboring island 185 miles to the east of Nauru.

William Harris was lucky, then, to arrive in Nauru after Jones had been cast off the island. Like other beachcombers, Harris helped the Nauruans to barter with passing Europeans. But he took a different tack with the Nauruans, integrating into their society by marrying a Nauruan and raising a large family. Harris would live on Nauru for nearly 50 years and witness island life change in ways unimaginable to any past generation of Nauruans.

By the 1870s, guns were in homes across the island, and Nauruans were smoking and drinking heavily (especially sour toddy, made by fermenting coconut flowers). After a chief was shot and killed during a drunken quarrel, Nauru began to spiral into violence. Retaliations were swift and deadly. Traditions for resolving conflict did little to slow the escalating feuds among clans and families. Neighbors slew each other, and skirmishes turned into bloodbaths. In 1881, the British Royal Navy dropped anchor off Nauru, and Harris boarded the flagship to inform the captain that a civil war had broken out on the island: “An escaped convict is king,” the captain communicated to his fleet. “All hands constantly drunk: no fruit or vegetables to be obtained, nothing but pigs and coconuts.”

At the time Nauru was of minor strategic value for the colonial powers jockeying in the Pacific. Then one day in 1899 the geologist Albert Ellis inspected a rock-like object that was propping open a door in the Sydney office of the Pacific Islands Company, a trading and plantation firm. He had been told it was a piece of petrified wood from Nauru. But this did not seem right to Ellis, and he would soon discover that it was actually high-grade phosphate ore, a super-fertilizer worth a potential fortune if he could locate the source.

The Phosphate Rush

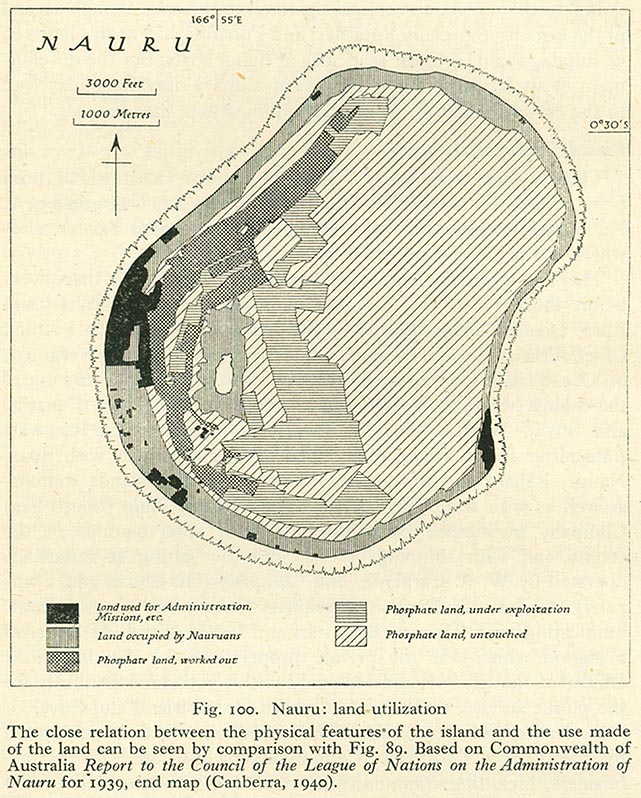

Sailing to Nauru in 1901, Ellis found that 80 percent of the entire island — the raised central plateau Nauruans call “Topside” — was rich in phosphate of lime. The Pacific Islands Company was renamed the Pacific Phosphate Company, and in 1905 a deal was made with Germany to mine Nauru. A year later the first boatload of Nauruan phosphate would sink in a storm off Australia. But this setback did little to deter miners and, over the next decade, Nauru would export hundreds of thousands of tons of phosphate.

Nauruans had never built homes on Topside, preferring the cooler shoreline; but Topside was home to wild almond and planted pandanus trees, as well as flocks of birds, including terns, noddies, and frigatebirds. Miners cleared the scrub, ferns, and trees, scraped away the topsoil, and then dug the ore out of the pits and crevices of the ancient coral underneath. Little care was taken. Photographer Rosamond Dobson Rhone, writing in 1921 for National Geographic Magazine, describes the aftereffects: “A worked-out phosphate field is a dismal, ghastly tract of land, with its thousands of upstanding white coral pinnacles from ten to thirty feet high, its cavernous depths littered with broken coral, abandoned tram tracks, discarded phosphate baskets, and rusted American kerosene tins.”

“A worked-out phosphate field is a dismal, ghastly tract of land … its cavernous depths littered with broken coral, abandoned tram tracks, discarded phosphate baskets, and rusted American kerosene tins.”

By this time Australia was ruling Nauru, having captured it from Germany at the start of WWI. It declared the island as an offshore mining site and began to focus on building mining infrastructure, mechanizing mining, and ramping up exports. By the early 1920s, Nauru was exporting some 200,000 metric tons of phosphate a year; two decades later it was more than four times that — all priced well below the world average to subsidize farmers in Australia, New Zealand, and Great Britain, a triumvirate of nations organized as the British Phosphate Commissioners and given mandate by the League of Nations.

Phosphate mining would briefly grind to a halt after Japan invaded Nauru in 1942. Japanese troops were merciless — with beatings, summary executions, deportations, forced labor camps, and mass drownings (such as of people with leprosy). At war’s end in 1945 fewer than 600 Nauruans remained on the island and a quarter of the Nauruan people had died. The United Nations put Nauru under a “trusteeship” of Australia, Britain, and New Zealand, with Australia once again administering the island.

The Nauruan phosphate industry was almost immediately revived, and a few years later exports were higher than ever. Over the next two decades exports would rise steadily, with Australian and New Zealand farmers continuing to pay far below market prices until 1963. By the time Nauru gained independence in 1968, more than 35 million metric tons of phosphate had left its shores — enough phosphate to fill dump trucks parked end to end from New York City to Los Angeles, and back again.

Independence

By 1968, one-third of Nauru had been strip-mined, and Nauruans were living on a narrow ring around a plateau of jagged, spiky, razor-sharp coral and limestone pillars. During the interwar years and again after WWII, Nauruan landowners did receive token royalties, and small trust funds were set up. The mining of Nauru’s phosphate was not outright theft; however, the Nauruan share was tiny considering the profits, damage, and cost of restoring mined land. After independence the Republic of Nauru chose to cash in its remaining phosphate, increasing exports despite knowing that supplies would run out within a generation or two.

By 1968, one-third of Nauru had been strip-mined, and Nauruans were living on a narrow ring around a plateau of jagged, spiky, razor-sharp coral and limestone pillars.

On paper, at least, Nauruans became wealthy over the next two decades. In 1975 Nauru’s Phosphate Royalties Trust was valued at well over A$1 billion and the country’s per capita gross domestic product was second only to Saudi Arabia. Most Nauruans certainly did not live in luxury. But the government did not tax incomes, provided free education and health care, and was the main employer for Nauruans (immigrants generally worked in mining). The government also bought cruise ships, aircraft, and overseas hotels, while politicians were known to charter flights to shop and vacation abroad. Curiously, during this time sports cars became a prized possession in Nauru, even though driving leisurely around the island takes 20 minutes. One police chief even imported a Lamborghini only to discover that he was too bulky to squeeze behind the wheel. “A lot of stupid things happened,” recalled Nauruan Manoa Tongamalo in 2008. “People would go into a shop, buy a few sweets, pay with a $50 note, and not take the change. They’d use money as toilet paper.”

During this time Nauru was also seeking compensation from Australia, New Zealand, and Britain for the damage done by mining before July 1967. As administrator, Australia knew well that mining was decimating Nauru. By the early 1960s Australia was proposing to resettle Nauruans in Australia, including an offer in 1963 of citizenship and limited self-rule on Curtis Island, just off the coast of Queensland. Yet after independence, Australia was unwilling to consider compensating Nauru and, after decades of delays and indifference, in 1989 Nauru took Australia to the International Court of Justice. Australia could see that Nauru had a strong case, and the parties settled out of court, with Australia agreeing to pay A$57 million in 1994 as well as another A$50 million over the next 20 years (later, the U.K. and New Zealand each contributed A$12 million to reduce Australia’s burden). To some extent, this settlement was a moral and legal victory for Nauru. But considering the damage, the compensation was a financial pittance.

The End of an Era

Trying to diversify the economy before phosphate supplies ran out, Nauru turned to offshore banking, licensing around 400 foreign banks by the early 1990s. Tony Audoa, in 1991 in charge of licensing banks, explained his government’s reasoning to The Australian: “After the phosphate industry comes to a close, we have to go into other areas that are sustainable and renewable each year.” But “illegal” would be a far more accurate adjective than “sustainable” or “renewable.” To open a bank it was not even necessary to visit Nauru, let alone open a branch on the island; even keeping bank records was optional. By the mid-1990s Nauru was also offering “economic citizenship”: selling Nauruan passports with little scrutiny. The Nauruan government did earn millions of dollars a year in fees. But these schemes turned Nauru into a haven for tax evasion and money laundering, with tens of billions of dollars of criminal profits washing through during the 1990s.

Offshore banking and selling passports could not fix Nauru’s economic woes. Desperate for revenue and jobs, with cruel irony Nauru agreed in 2001 to allow Australia to establish a detention center on Nauru to process asylum seekers who’d been trying to reach Australia by boat. By 2002, some 1,000 asylum seekers — mostly Afghan and Iraqi — had been ferried to Nauru, and for a few years Australian aid and processing fees added millions to Nauruan government coffers. Even this scheme, however, could not patch the gaping hole in Nauru’s economy as primary phosphate reserves ran out. Through the 1990s, phosphate exports had been in steady decline. In 2000, Nauru did manage to export another 500,000 metric tons. But by 2004 Nauru’s phosphate boom was truly over, with exports tallying just 22,000 metric tons.

During the 1990s, Nauru became a haven for tax evasion and money laundering, with tens of billions of dollars of criminal profits washing through it.

By then Nauru’s economy was in tatters. The government still wasn’t collecting income tax, while the public service was by far the main employer of Nauruan nationals. State investments had gone awry, and with years of recurring deficits the government had been borrowing heavily from Nauru’s sovereign wealth fund to stay afloat. Struggling to pay public service wages and defaulting on loans, in 2004 the Nauruan government agreed to allow Australia to step back in to manage the country’s finances.

At the time Australian economist Helen Hughes did not see much complexity behind Nauru’s fiscal woes: “They have blown close to two billion.” From 1968 to 2002, phosphate earned Nauru A$3.6 billion, with about A$1.8 billion in profits. Invested judiciously, Hughes estimated that Nauru’s Trust Fund could have been worth A$8 billion by 2004, with each Nauruan family pocketing A$4 million. Yet by 2004 Nauru’s Trust Fund was worth A$30 million at most. Hughes did not lay all the blame on local corruption and incompetence. “There’s always the sharks that swim in the Pacific,” she would tell The Australian in 2010. Nauruans “have a long history of being taken to the cleaners by crooks.”

Worse economic news was still to come. In 2005, phosphate exports fell to a record low of 8,000 metric tons. That same year Nauru began to require a “physical presence” to license a bank in the country, effectively ending offshore banking. Nauru had been under intense international pressure to stop money laundering and the granting of economic citizenship — the U.S. government even went as far as using the 2001 Patriot Act, which gives it the power to prohibit American banks from dealing with “rogue state” institutions, to go after Nauru for selling its passports.

Today, Nauru is still searching for a place in the world economy. Since 2006 it has upgraded mining equipment and refurbished mining infrastructure to dig out harder-to-reach phosphate. But its phosphate industry, mining around 45,000 metric tons a year, is producing nothing like in the past. Below the sprinkling of primary surface phosphate still left on Topside, Nauru does have secondary reserves of phosphate — perhaps as much as 20 million metric tons. Plans are underway to mine this last remaining phosphate. But no one sees this as a long-term solution for its economic troubles.

A Colony of Refugees

In 2007, Australia shut its detention camp on Nauru, only to reopen it again in 2012. “I’ve been to Nauru and Nauru is quite a pleasant island,” then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott said on Australia’s “Lateline” in 2013. “Nauru is by no means an unpleasant place to live.” Another time Abbott even talked of expanding the Nauru camp to hold as many as 15,000 asylum seekers — this, on an island with no natural water supply. By 2014 there were more than 1,200 asylum seekers — Afghans, Sri Lankans, Pakistanis, Iraqis, Iranians — living in tents fenced in on Topside. Dusty and parched in the dry season, the detention and processing center is muddy and miserable in the wet season.

Detainees have gone on hunger strikes and sewn their lips together; in July 2013 a riot broke out, destroying much of the detention facility. It was quickly rebuilt. Amnesty International’s Graham Thom describes the camp as “not only extraordinarily ill-conceived, but cruel.” Marianne Evers, an Australian nurse who worked at the camp for three weeks in 2012, broke her confidentiality agreement and spoke out on Australian TV in 2013: “There is absolutely nothing to do. There are no trees. There is no grass. There is not even that many birds there. So we live in that heat without air conditioning in tents. It is just desperation that I can’t get out of my head. Of all of them.”

The processing of asylum seekers is once again winding down in Nauru. There were around 350 people awaiting processing in early 2019, according to the Refugee Council of Australia. Life is far from pleasant for them, even for those able to move freely about the community. One of the women originally from Iran, after nearly seven years in Nauru, attempted suicide in May 2019. “It is like a slow death for me. I don’t want to come to Australia any longer. My only desire is death,” she told the Guardian Australia.

Desperation seems to pervade all of Nauru. High unemployment is endemic. With few restaurants and only a handful of hotels, Nauru has little tourism. Landing by air the island looks alluring; up close, you find rusting cars, rundown houses, and rotting garbage. “Nauruan homes are very basic and often seem partly built,” Australian journalist Kathy McLeish wrote in 2013. “Rubbish litters roads and yards, while decades-old infrastructure is broken and left to decay.”

“There is absolutely nothing to do. There are no trees. There is no grass. … So we live in that heat without air conditioning in tents.”

Australian aid has long been propping up the Nauruan economy. Offshore fishing licenses provide some government revenue, too — as does selling the remaining phosphate. In recent years bingo is the only private sector activity that’s been thriving — and the government is finally trying to tax the game. But it is visa fees that have been injecting millions of dollars into the country’s budget, as Australia pays a monthly charge for each asylum seeker detained in Nauru.

Excluding asylum seekers, some 10,000 people now reside on Nauru. Almost all food is imported; even fresh water is shipped in when the desalination facility fails to meet needs. Processed and canned food makes up much of a diet heavy in salt, sugar, and artificial ingredients. Nauru has one of the world’s highest obesity rates, with more than two-thirds of Nauruan men and three-quarters of Nauruan women obese, as well as one of the highest rates of smoking. And around a quarter of all Nauruan adults suffer from diabetes. Alcoholism is endemic too, contributing to domestic violence and frequent drunk-driving offenses, even though all of the country’s roads cover just 19 miles (30 kilometers).

Turning Back Time

Since the early 1900s, Nauru has lost at least 80 percent of its original vegetation. Over this time Nauru has exported around 80 million metric tons of phosphate. If dump trucks could fly, this amount of phosphate could fill enough trucks to link them bumper to bumper from New York City to Tokyo — and then go back. All of this phosphate came from an island one-third the size of Manhattan.

James Aingimea, a minister of the Nauru Congregational Church who in 1999 passed away at the age of 88, dreamed of turning back time in the last years of his life. Speaking in 1995 with Philip Shenon of the New York Times, he lamented: “I wish we’d never discovered that phosphate. I wish Nauru could be like it was before. When I was a boy, it was so beautiful. There were trees. It was green everywhere, and we could eat the fresh coconuts and breadfruit. Now I see what has happened here, and I want to cry.” Minister Aingimea’s wish will never come true. But he knew that. Already in 1995 he was pondering whether it was finally time to abandon the island. “It would be very sad to leave our native island,” he said. “But what else can we do? The land of our ancestors has been destroyed.” And climate change is bringing even more troubles to Nauru.

Droughts and storms are intensifying, and rising seas are eroding the coastline. One day Topside may be all that remains, a reminder of the folly of greed and the irony of Captain Fearn naming the Nauruan land Pleasant Island.

Peter Dauvergne is Professor of International Relations at the University of British Columbia. He is the author of several books, including “The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment,” “Eco-Business: A Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability” (with Jane Lister), and “Environmentalism of the Rich,” from which this article is adapted.