Cinema and Cycling, Technological Twins

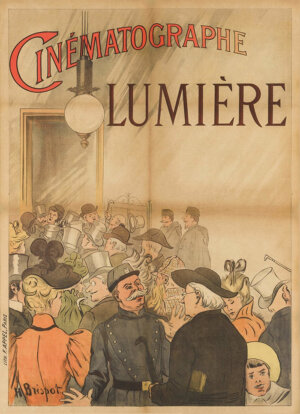

For many cinema historians, the screening held by Auguste and Louis Lumière in the Salon Indien of the Grand Café in Paris on December 28, 1895 marks the birth of cinema. Cinema emerged in multiple locations at different times and in different formats, such as Edison’s first Kinetoscope parlour in New York in April 1894, or the screening of large-format Bioscop films by Max and Emil Skladanowsky in Berlin in November 1895.

However, it was the Lumière screenings, and the practicality of their lightweight, all-in-one camera/film-developer/projector, the Cinématographe, that secured the medium’s success. The admission charge was a franc for a program of 10 single-shot films, each lasting less than 50 seconds, and within weeks spectators were waiting in long lines to catch one of the 20 shows a day the Lumières were offering. Thus, the entry of this new medium into global culture coincided with the cycling boom of 1895, and this coincidence is marked emphatically by the first film in the program.

The first screenings opened with the film “La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon,” which shows workers leaving the Lumières’ photographic factory, passing through the factory gates and heading off in different directions along the road outside the factory. There are three existing versions of the film, the first of which — the first film they shot — was filmed on March 19, 1895. The subject is bodies in motion, but, more specifically, we see scores of industrial laborers, the vast majority women, spilling out of the factory at the end of a shift. The film, which is itself an artifact of new industrial technology, presents us with a symbolic image of industrial modernity as a crowd of workers stream through the gates towards the camera. Film historian Tom Gunning has observed:

The twentieth century might be considered the century of the masses, introducing mass production, mass communication, mass culture. We could redescribe this transformation as the entrance of the working class (putatively the driving force of any age, but often eclipsed in the realm of official representation) onto a new stage of visibility.

The cinema is a crucial component of this ‘stage,’ and it is appropriate that the film shows us a photographic factory, a crucial infrastructural component of the emergent mass culture. The other nine films include shots of a baby being fed, trick horse riding, a practical joke, a street scene and blacksmiths at work, but it is the factory-gate film that condenses the accelerating social changes into a single moving image. One rarely noted detail is that, as well as pedestrians, dogs and horse-drawn carts, all three versions of the film feature cyclists pushing through the crowd.

One rarely noted detail is that, as well as pedestrians, dogs and horse-drawn carts, all three versions of the film feature cyclists pushing through the crowd.

The composition of the image is roughly the same in all three versions, the camera placed at head height across the street from the factory gates. In the first film, among the workers on foot, a man wheels his bicycle through a doorway to the left of the gates, and begins to mount it, while a horse and cart emerge from the gates, followed by another cyclist pedaling behind it. In the second version, a younger cyclist in a flat cap squeezes through the crowd and cycles quickly off to the left, followed shortly afterwards by another man in a straw boater who is trying to ride through a group of women; he is forced to dismount, though, and pushes his bicycle out of the frame on the right-hand side, talking to one of the women behind him. A third cyclist, again sporting a straw boater, then emerges from the gates in front of a horse-drawn cart, and cycles across the frame from right to left, smiling at the camera as he passes in front of it.

In the third film, a man in a straw boater runs out of the crowd, steering a bicycle on which an identically dressed young boy is mounted precariously. Shortly afterwards another man wheels a bicycle through the doorway on the left, this time with a colleague perched on it. While they wheel cautiously along the pavement and out of the frame, a man in a flat cap cycles confidently off to the left on a bike with drop handlebars, and another cyclist peels off to the right. Just before the end of the film a fifth cyclist comes through the gates and is slapped vigorously on the back by one of his workmates, causing him to wobble unsteadily, and, as he moves out of the frame, the factory gates begin to close behind him.

Film historian Richard deCordova has argued that early cinema constituted a radical, disorienting distortion of familiar representational conventions, “a violent decomposition of the perspectival system that had been dominant since the 16th century in painting (the system upon which photography had been modelled).” What was disorienting for audiences about these first film sequences was not simply the illusion of movement but that figures moved towards the camera: ‘The workers do not just move: they move in perspective,” writes deCordova. For deCordova, this is shown most clearly by the way that the cyclists in “La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon” are initially hidden but then emerge from behind members of the crowd — an effect impossible to produce in painting or photography. In pushing their way past their co-workers and riding out of a photographic factory, the cyclists introduced 19th-century viewers to three-dimensional cinematic space, showing them the new ways of seeing the world offered by the cinema. Cycling is not an incidental element here; rather, the presence of moving bicycles in this film demonstrated the unique formal properties of this revolutionary medium: it is cycling that makes this film a film. In short, the first film is a cycling film.

It is unlikely that viewers of “La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon” realized they were witnessing a new order of pictorial space and the beginnings of a cultural revolution. However, there are enough anecdotal accounts of audiences’ confusion and anxiety at the uncanny spectacle of moving images to suggest that viewers felt intensely that they were seeing something more than just a diverting novelty, something radically new. By contrast with a static painting or still photograph, the film image undergoes continuous transformation. As deCordova observes, “the elements are in constant flux — in a mechanical movement,” but, in retrospect, it is clear not just that this film is an early example of the visual spectacle of mechanical movement, but that it is also a document of a society undergoing radical transformation through mechanical movement — a high-tech, industrialized, globalized society in constant flux.

This film is not only an early example of the visual spectacle of mechanical movement, but also a document of a society undergoing radical transformation through mechanical movement.

The bicycle is an ideal subject for the first film since, in western Europe in 1895, it was an increasingly ubiquitous, visible and thrilling example of mechanical movement, as well as a harbinger of the ways in which modern life would become progressively dominated by mechanical motion.

Indeed, enthusiasm for both cinema and cycling coincided with the height of the second industrial revolution in Europe and the United States, which was marked by the development of the steel industry, chemical manufacturing, electrification, the refinement of mass production techniques and the expansion of the railway system. Cycling and cinema were products of this interval of intensive technical innovation and rapid, disorienting change, made possible by new developments in engineering. They were particularly visible signs of the economic, social and cultural transformations that swept violently across the globe during this period, altering the ways that people interacted with one another and experienced their own bodies, and the ways in which they understood and represented their place in the world.

Bruce Bennett is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies in the Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts (LICA) at Lancaster University, and the author of “Cycling and Cinema,” from which this article was adapted.