Chekhov and Memory

The peculiar nature of human consciousness allows us to reflect on ourselves. We can see ourselves in the moment, as we read this page or walk down the aisle of the grocery store, or see ourselves in the mirror washing our face in the morning. But we can also picture ourselves retrospectively when we think back on our childhood, and prospectively when we anticipate lying on the beach next month, giving birth in three months, or finding a new job in the new year. Nothing is more certain than that I exist, unique from all others who live, have lived, and ever will live. How are these separate selves all recognizable as “me,” given how much “I” change over the course of a lifetime?

The neuroscientist Anil Seth proposes that the apparent continuity of selfhood is to some extent a fine and useful trick that keeps us alive. The body knows itself through a continuous communication between brain, gut, limbs, and the senses. Seth explains that the biological functions of this misperception are critical to self-preservation. The continuity of self doesn’t require conscious effort. It just requires memory. Our ability to keep our multiple selves integrated is the bedrock of our resilience in a world that constantly changes.

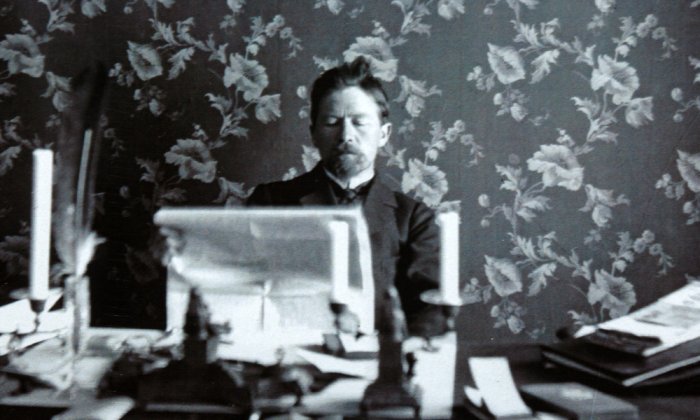

In his stories and plays, Anton Chekhov depicted memory as the vital link that not only keeps people physically and mentally whole, but at a deeper level is the source of having hope not despair, knowledge not ignorance, and kindness not cruelty. Memory is the great sifter of human values. Chekhov was a physician who began writing when young to earn money for his tuition, and then to support his large family — his despotic, bankrupt father, long-suffering mother, devoted sisters, and importunate, feckless brothers. He frequently complained about needing money but on occasion would turn down a commission. While in Nice in the winter of 1897, Chekhov received a request from his editor at Cosmopolis for a story taken from his life abroad. He declined. “I can write only from memory,” he replied, “and have never written directly from nature. I must have my memory process a subject, like a filter that leaves only what is important and characteristic.” That winter, instead of writing about the sunlit pleasures of life on the Mediterranean, he turned out stories about young women and men living deep in the Russian provinces with little prospect of escaping from the tedium of their lives — all this from memory.

Chekhov’s great subject was memory itself, with its power to endow a life, no matter how humble, with meaning and, on occasion, states of pure bliss.

At first, this insistence on letting time do its work seems paradoxical, given how vividly Chekhov’s stories incorporate extremely precise, well-observed details that come from everyday life — the way a farm smells of hay, warm manure, and steaming milk in June; that moment of transformation when a singer goes to the top of her range and sounds more birdlike than human; the violet glow of the sea at sunset in the Crimea. These details are not bits of journalistic color, nor are they mere word-count padding (Chekhov got his start by cranking out comic stories and gags for newspapers that paid by the word). These details were elements of the world that bound his characters in time and place and from which they could not escape.

Chekhov made his observation about memory when he was 37 years old. He wintered in the south of France to give his tubercular lungs a rest from the dry frigid air of Moscow. Chekhov was born in 1860, when life expectancy was somewhere in the mid-40s. Atul Gawande has remarked that in 1900, “old age was not seen as something that increased your risk of dying, as it is today, but rather as a measure of good fortune.” Chekhov was not apportioned that measure of good fortune. He died of tuberculosis when he was 44, after years of suffering symptoms of weakness, insomnia, irregular heartbeat, chills, and fevers. He first noticed ruby-red sputum coughed up from his lungs when he was only 25. There was no cure for his disease, but his symptoms could be somewhat relieved by spending time in the south, so he wintered in the Riviera or Crimea.

Chekhov read deeply in Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and others who articulated a revolutionary view of human nature. In this view, humans are thoroughly naturalized, subject to the large-scale evolutionary forces that respond to random events in the environment — a fire that destroys a thriving habitat, a new bacterium that infects a population, a decade of drought. The fate of humanity is no different from the fate of other species. There is no special destiny set out for it. Chekhov was a thoroughgoing Darwinian who spoke with equanimity about outbreaks of cholera as the way that nature culls the weak, even as he was working 20-hour days in his clinic to alleviate the pain and suffering of those affected by the disease. His task as a writer was identical to his task as a doctor and man of science. A writer, he wrote in a letter to Maria Kiselyova, is

a person with an obligation, bound by his awareness of his duty and by his conscience; once he has taken up the pen, there’s no turning back, and no matter how terrible something seems, he is obligated to overcome his squeamishness and sully his imagination with the filth of life. . . .

To a chemist, nothing on earth is unclean. A writer must be as objective as a chemist; he must renounce ordinary subjectivity and understand that the dung heaps on the landscape play a venerable role, and that evil impulses are as much a part of life as the good ones.

That said, his great subject as a writer was not the dung heaps on the landscape. It was memory itself, with its power to endow a life, no matter how humble, with meaning and, on occasion, states of pure bliss. In his plays and short stories, memory becomes more than a noun. It is a verb, an action fleeting and ephemeral, that makes sense of the otherwise random and senseless lives people lead.

Chekhov is said to have been tender, kind, compassionate. As a man, he may have been these things to his friends and patients, but never as a writer. In his stories and plays he depicted people without flattery. Given his acumen as a physician and diagnostician, he made observations that were precise and unsparing. This frankness was not intended to shock, dismay, or dishearten his readers. “The artist is not meant to be a judge of his characters and what they say; his only job is to be an impartial witness.” Few of his characters are masters of their own fate, and even fewer are eager to take responsibility for themselves, let alone others. Chekhov had a dim view of humans’ capacity for self-understanding. Time and again, his characters meet misfortune and are degraded by it. They cheat and are cheated. They lie to themselves and they lie to others. Angry and despairing, they drink to excess. Or they live in indolence, out of cowardice, and keep quiet when they should speak up. We read of people who are offered a chance at happiness and don’t notice it. Or if they do notice it, they turn it down, out of vanity or a passing spasm of spite, or they fret and grow anxious about change and take to their beds. Above all, they succumb to self-pity. They dwell in the past, enumerating their regrets. They worry about the future, paralyzed by anxiety. They stand still and life passes them by.

Yet his stories are studded with moments of gratuitous grace, fleeting as meteors in the moonless night sky, leaving traces long on the retina and even longer in memory. Where do these moments of grace come from? They are always the fruit of a memory stimulated haphazardly and appearing full-blown as a feeling and a vision. The character time-travels to a happier moment, is suffused with contentment, and catches a glimpse of paradise lost, perhaps, but nonetheless real in the moment. It reminds the reader (though seldom the character) how mysteriously, ineluctably, events in the present are linked to the past. Hopes crushed by life, buried beneath layers of disappointment and bitter experience, can return to us in a flash as emeralds or sapphires hardened into crystalline perfection under the tectonic pressures of the earth. For Chekhov, only with the passage of time can we grasp the meaning of an event or a feeling. But we must be patient and bear much pain before anything becomes clear to us.

For Chekhov, only with the passage of time can we grasp the meaning of an event or a feeling.

Among Chekhov’s most affecting works are those that walk right up to the mystery of life’s bitter unfairness and stand still to let us gaze at it. We know it intimately through the unadorned imagery of his prose and unexplained behaviors of his characters. Then, depending upon Chekhov’s mood, he either slaps us in the face (thus making it a comedy) or he steps away and leaves us in a state of wonderment, looking through the door he leaves open for us as he disappears.

In “The Lady with the Little Dog,” the married protagonist Gurov casually starts an affair while on vacation in the Crimea. It wasn’t out of boredom or restlessness, but just his habit of checking out the women wherever he happened to be and making one the target of his seduction. He chose someone he spotted walking on the seaside promenade with her dog. Anna Sergeevna was no more interesting and certainly no more beautiful than any other woman he had dallied with. But for some reason he couldn’t account for, when they parted, he couldn’t forget her. After he returned to his habitual life in Moscow, her image “would be covered in mist in his memory.” Over time, “the memories burned brighter and brighter.” Then they would “turn to reveries, and in his imagination the past would mingle with what was still to be. Anna Sergeevna was not a dream, she followed him everywhere like a shadow and watched him.”

What does the filter of memory reveal to Gurov that he could not otherwise know? As time did its work, sifting through the moments of his life, it left behind the one thing that meant anything to him—the strange, unprepossessing woman without whom he could not live. “Closing his eyes, he saw her as if alive, and she seemed younger, more beautiful, more tender than she was; and he also seemed better to himself than he had been then, in Yalta.” Perhaps these images were a trick of memory, but they revealed the truth to him. There was no escape in the end; his fate was attached to hers. He came to the tormented realization that he loved her. He had never expected to love, he never wanted to love, he didn’t know how to love. Through no power of his own, he became attached to her, and through her, he became attached to the world, something he had never looked for, never wanted, and that he knew was only going to make his life more complicated: “And it seemed that, just a little more—and the solution would be found, and then a new, beautiful life would begin; and it was clear to both of them that the end was still far, far off, and the most complicated and difficult part was just beginning.”

Only in Chekhov can we read that lovers are finally united and that is when the difficulties begin. Only in his tales about the vanity of human ambition and the emptiness of people’s promises can we find so much happiness overtaking a poor soul that he feels it almost as an affliction. What does this mean? It was through the work of memory that Gurov found his place in the world. That place was with Anna Sergeevna.

Abby Smith Rumsey is an intellectual and cultural historian. She chairs the board of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University and is the author of “When We Are No More: How Digital Memory Is Shaping Our Future” and “Memory, Edited,” from which this article is excerpted.