Calypso Confusion

After Harry Belafonte scored a hit in 1956 with his best-selling album “Calypso!,” almost overnight, calypso became the top-selling music in North America. Belafonte, although from New York, had spent time in Jamaica while growing up because both his parents were from the West Indies. His celebrity status — singer, Broadway and television performer, film star — helped propel calypso into mainstream U.S. consciousness. Hollywood chipped in with films such as “Calypso Heat Wave” (1957) and “Bop Girl Goes Calypso” (1957).

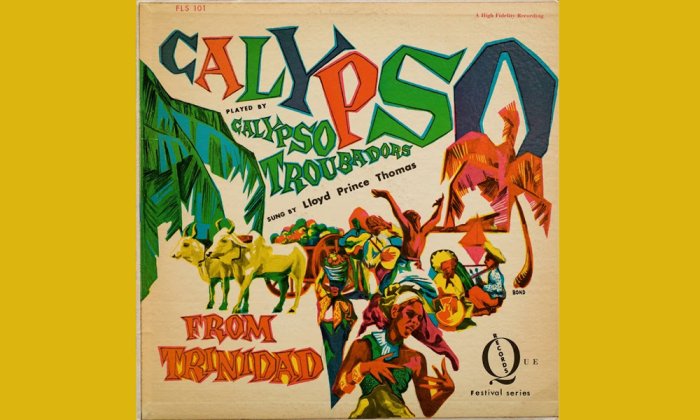

Where is calypso really from, though? Belafonte’s Calypso album celebrated Jamaica and sold more than a million copies. “Day-O” immediately became associated with the genre. Not a simple marketing challenge, then, to address a fundamental error: Calypso is from Trinidad, not Jamaica.

As Carnival music from Trinidad, calypso is not limited to a particular dance or set of steps. It certainly houses rhythms, sometimes for marching and dancing through the streets but also for carrying stories, spontaneous lyrics, and commentary — sometimes layered with meaning, sometimes straight-up political in message. Calypso “battles” form a kind of popularity contest for choosing the best numbers. Detailed liner notes on “Calypso!” (1957) by the Duke of Iron and the Fabulous Steel Bands describe this process: “Calypsoians are chosen under the stiffest possible competition. Their acceptance is passed upon by the older masters who select the most talented young singers of the Lenten Carnival. The winners of these battles of humor, wit and invective emerge as true Calypsoians, who must create their songs on the spot. It is said they must be Trinidadian.”

Calypso evolved from West African musical forms, including Kaiso. The liner notes for “Calypso from Trinidad” (1957) provide insight: Calypso “grew out of slavery, when the Spaniards brought Africans to Trinidad in the 17th century. Slaves couldn’t talk while they worked, but the overseer let them sing because they worked better that way. So, singing in their native dialects, the slaves exchanged news, gossip, and even acid opinions about their masters.” The notes also address origins: “Many theories have been advanced by devotees concerning the origin of this music with its African beat and witty lyrics reminiscent of the French troubadours. However, all agree that it was rooted in the early days of slavery and colonization.”

Calypso songs tell tales of adventure and avarice, using wordplay, exaggeration, and puns, often with sexual innuendo. The catchy calypso standard “Rum and Coca-Cola” offers critical commentary on the U.S. military’s presence in Trinidad. According to researcher Michael Eldridge, when popular singing trio the Andrews Sisters recorded their version in 1944, “it was banned from the major U.S. networks and became one of the most popular hits in the country. If the words seem clear enough in print, few who hum along to the tune today seem to notice that ‘working for the Yankee dollar’ means prostitution.” The development and evolution of calypso tunes and lyrics presented complications for those attempting to claim songwriting credits and copyrights, and “Rum and Coca-Cola” was infamous for legal squabbles over authorship and royalties.

As for how to dance calypso: Calypso dancing is Carnival dancing. As scholar Cynthia Oliver describes it: “Calypso, a product of Carnival, is a dance where the feet sometimes shuffle, sometimes lift gracefully off the floor as the upper body remains stoic and the waist and hips twist and bounce.” Major U.S. record labels had been releasing calypso records since the 1930s. In dance-craze America of the 1950s, calypso morphed into a popular, mainstream dance style. Not surprisingly, Calypso as danced by most Americans was an amalgam of earlier ballroom styles and had little connection to West Indian Carnival dance.

In 1957, the hot question was, Will Calypso doom Rock ’n’ Roll? “An incredible number of Calypso records were rushed to the market, nightclubs around the country switched to an all-calypso policy, and many in the industry came to believe that rock ’n’ roll was dead and that calypso was taking over,” write music historians Ray Funk and Donald R. Hill. Rock and roll rumbled on, however, and calypso never reached the success hoped for by the recording industry. While it lasted, though, performers from across the musical spectrum tried their hand at making calypso records, including Latin musicians Joe Loco and Tito Puente, folkies Burl Ives and the Kingston Trio, jazz singers Dinah Washington and Ella Fitzgerald, West Indian natives Maya Angelou and Josephine Premice, and actor Robert Mitchum.

While one listens to and looks at midcentury calypso records, it is worth remembering that at the height of the calypso craze, the home of calypso was mired in struggles to break free from colonialism. There was an uneasy relationship between the American quest for new dances and new identities and a growing West Indian movement to establish independent states. For example, in Trinidad, amidst a growing nationalist sentiment, many wanted steel bands to play only “local” — instead of foreign (European classical) — music. Calypso music, however, proved adaptable and marketable, though it was surpassed by Caribbean reggae and subsumed into salsa.

Album covers offer compelling representations of cultural expectations, desirable experiences, and social interactions. Midcentury calypso record covers drew on a repertoire of powerful, pleasurable associations of island life, fueled by the travel industry’s images of tropical paradise. In turn, interest in traveling to the islands, the home of “Day-O,” sent American consumers to travel agents for resort holidays and Caribbean cruises. Embedded in national and international struggles over narrative control, dances and their origin stories reveal political positioning. What does it mean to claim affiliation and identities in such a context? Midcentury record albums express these struggles.

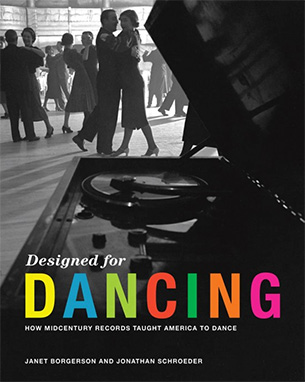

Janet Borgerson is Wicklander Fellow at DePaul University and coauthor (with Jonathan Schroeder) of “Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America” and “Designed for Dancing: How Midcentury Records Taught America to Dance,” from which this article is adapted.

Jonathan Schroeder is William A. Kern Professor in the School of Communication, Rochester Institute of Technology.