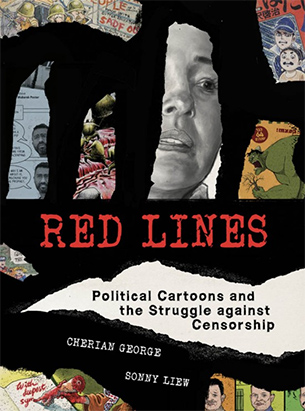

An Illustrated Guide to Post-Orwellian Censorship

The political cartoon is the art form of our deeply troubled world; a chimera of journalism, art, and satire that is elemental to political speech. Cartoons don’t tell secrets or move markets, yet as Cherian George and Sonny Liew show in “Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle against Censorship,” cartoonists have been harassed, sued, fired, jailed, attacked, and assassinated for their work.

As “drawn commentary on current events,” the existence and proliferation of political cartoons provides a useful indicator of a society’s state of democratic freedom: It shows that the system requires powerful individuals and institutions to tolerate dissent from the weak; and that the public is used to freewheeling, provocative debate. But that is not the norm. In most countries, political cartoonists — the guerrillas of the media — are vulnerable to multiple and varied threats. In the excerpt that follows, George and Liew examine China and Turkey to illustrate that while totalitarianism may be out of style, what remains is no less insidious.

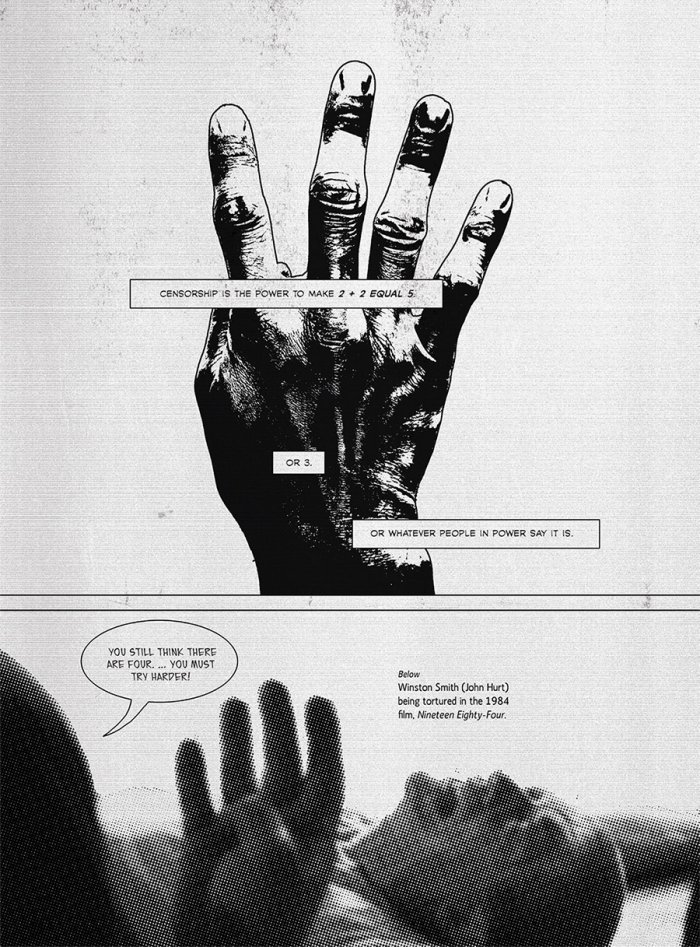

Censorship is the power to make 2 + 2 equal 5. Or 3. Or whatever people in power say it is.

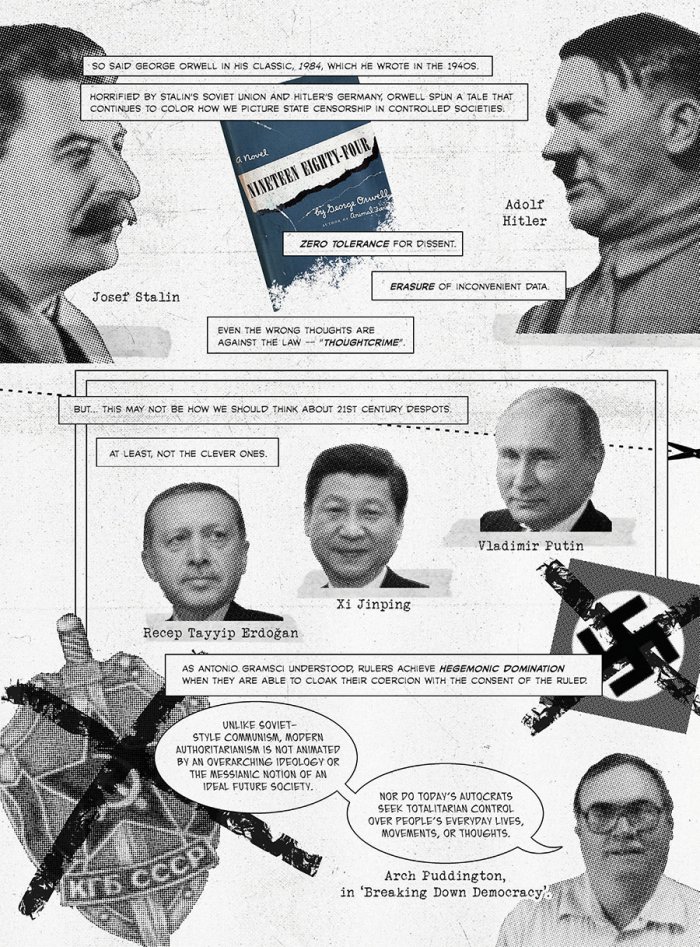

You still think there are four. … You must try Harder! So said George Orwell in his classic, “1984,” which he wrote in the 1940s. Horrified by Stalin’s Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany, Orwell spun a tale that continues to color how we picture state censorship in controlled societies. Zero tolerance for dissent. Erasure of inconvenient data. Even the wrong thoughts are against law — “Thoughtcrime.”

But this may not be how we should think about 21st-century despots. At least, not the clever ones. As Antonio Gramsci understood, rules achieve hegemonic domination when they are able to cloak their coercion with the consent of the ruled.

Hannah Arendt, a close observer of totalitarian regimes, realized that power needs legitimacy, which is destroyed when violence is overused.

In the 1980s, Miklós Haraszti in communist Hungary observed that arts censorship in a mature one-party state was quite different from the terror of Stalinism. Stalinism was paranoid, hard, and military-like. It required complete consensus, and loud loyalty — “Neutrality is treason; ambiguity is betrayal.” Art was forced into a propaganda role.

Post-Stalinist regimes were more confident, and therefore softer. They expanded the boundaries of the permissible. Make no mistake — modern authoritarians haven’t undergone a philosophical conversion to liberal values. They still use brutal methods. But paradoxically, if we overestimate their use of fear and force, we underestimate their power and resilience.

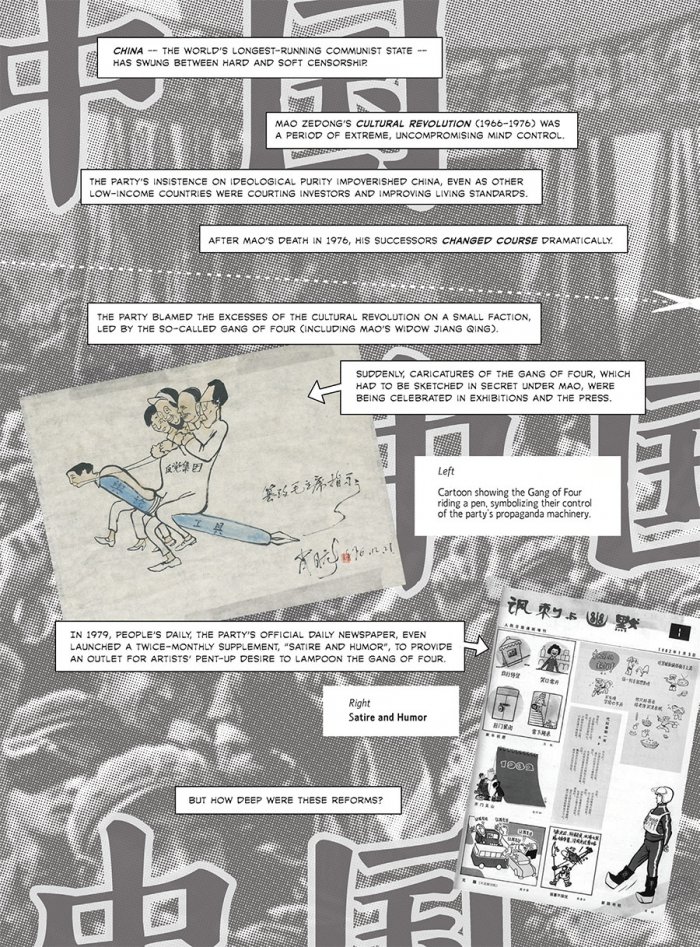

China — the world’s longest-running communist state — has swung between hard and soft censorship. Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution (1966–1976) was a period of extreme, uncompromising mind control. The party’s insistence on ideological purity impoverished China, even as other low-income countries were courting investors and improving living standards. After Mao’s death in 1976, his successors changed course dramatically.

The party blamed the excesses of the cultural revolution on a small faction, led by the so-called Gang of Four (including Mao’s widow Jiang Qing). Suddenly, caricatures of the Gang of Four, which had to be sketched in secret under Mao, were being celebrated in exhibitions and the press.

In 1979, People’s Daily, the party’s official daily newspaper, even launched a twice-monthly supplement, “Satire and Humor,” to provide an outlet for artists’ pent-up desire to lampoon the Gang of Four.

But how deep were these reforms?

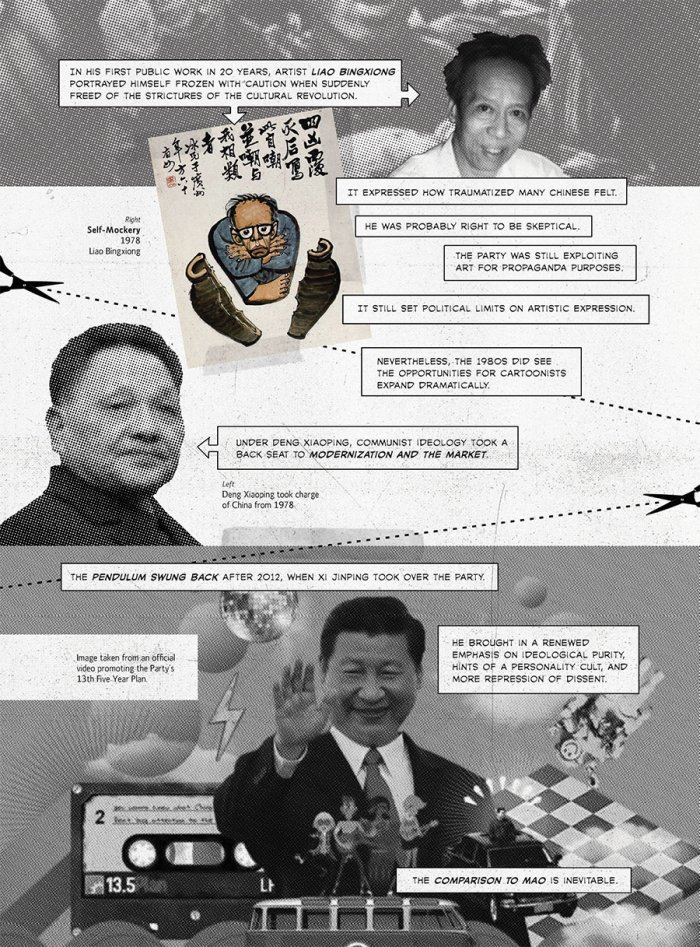

In his first public work in 20 years, artist Liao Bingxiong portrayed himself frozen with caution when suddenly freed of the strictures of the cultural revolution. It expressed how traumatized many Chinese felt. He was probably right to be skeptical. The party was still exploiting art for propaganda purposes. It still set political limits on artistic expression.

Nevertheless, the 1980s did see the opportunities for cartoonists expand dramatically. Under Dent Xiaoping, communist ideology took a back seat to modernization and the market. The pendulum swung back after 2012, when Xi Jinping took over the party. He brought in a renewed emphasis on ideological purity, hints of a personality cult, and more repression of dissent.

The comparison to Mao is inevitable.

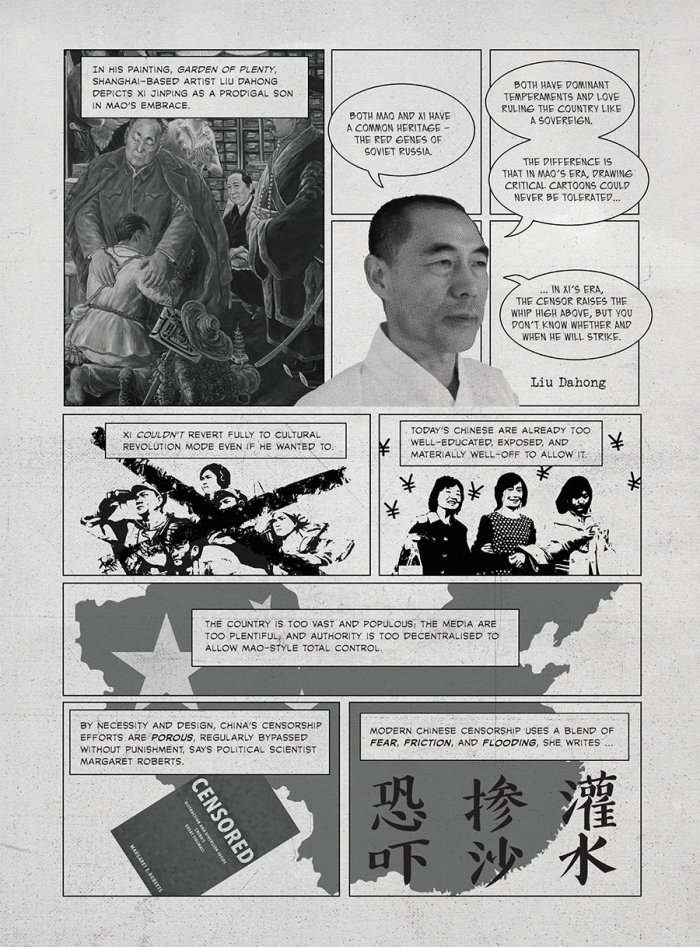

In his painting, “Garden of Plenty,” Shanghai-based artist Liu Dahong depicts Xi Jinping as a prodigal son in Mao’s embrace. Xi couldn’t revert fully to cultural mode even if he wanted today. Today’s Chinese are already too well-educated, exposed, and materially well-off to allow it.

The country is too vast and populous. The media are too plentiful, and authority is too decentralized to allow Mao-style total control.

By necessity and design, China’s censorship efforts are porous, regularly bypassed without punishment, says political scientist Margaret Roberts. Modern Chinese censorship uses a blend of fear, friction, and flooding, she writes.

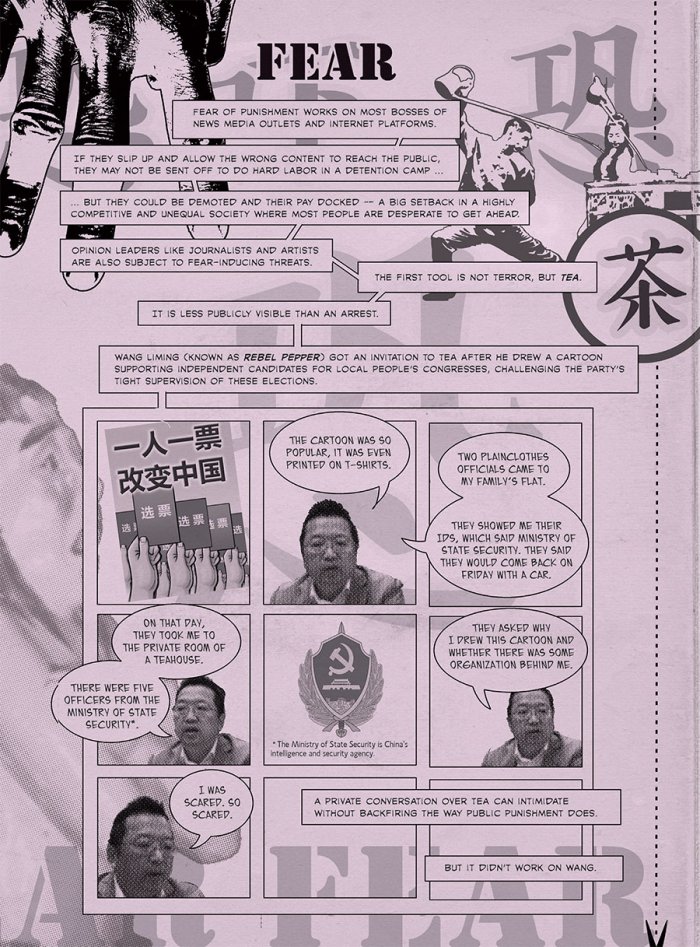

FEAR

Fear of punishment works on most bosses of news media outlets and internet platforms. If they slip up and allow the wrong content to reach the public, they may not be sent off to do hard labor in a detention camp, but they could be demoted and their day docked — a big setback in a highly competitive and unequal society where most people are desperate to get ahead.

Opinion leaders like journalists and artists are also subject to fear-inducing threats. The first tool is not terror, but tea. It is less publicly visible than an arrest. Wang Liming (known as Rebel Pepper) got an invitation to tea after he drew a cartoon supporting independent candidates for local people’s congresses, challenging the party’s tight supervision of these elections. A private conversation over tea can intimidate without backfiring the way public punishment does. But it didn’t work on Wang.

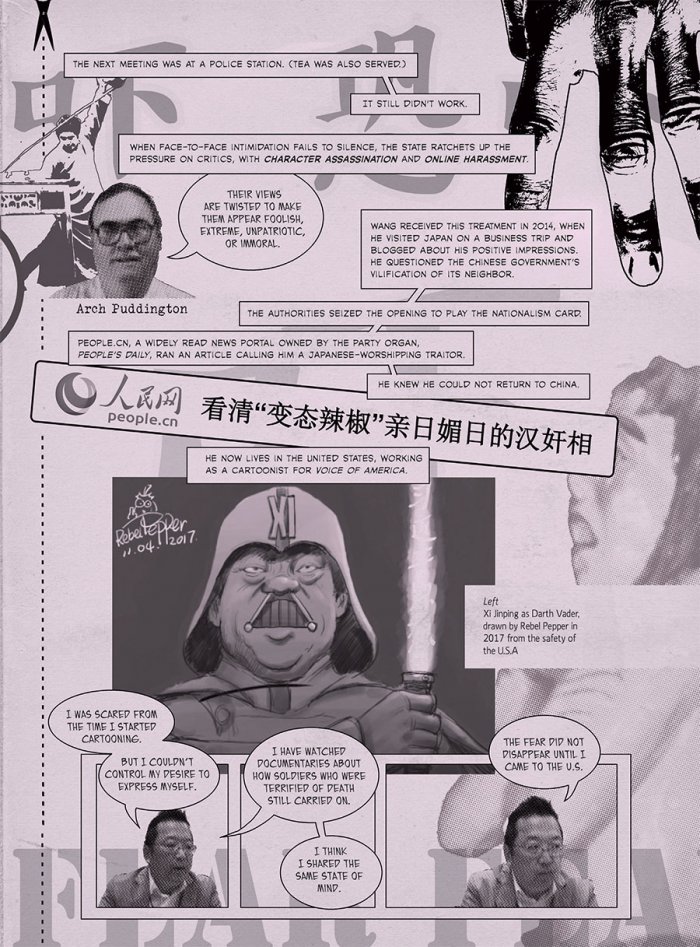

The next meeting was at a police station. (Tea was also served.) It still didn’t work. When face-to-face intimidation fails to silence, the state ratchets up the pressure on critics, with character assassination and online harassment.

Wang received this treatment in 2014, when he visited Japan on a business trip and bogged about his positive impressions. He questioned the Chinese government’s vilification of its neighbors. The authorities seized the opening to play the nationalism card.

People.cn, a widely read news portal owned by the party organ, People’s Daily, ran an article calling him a Japanese-worshipping traitor. He knew he could not return to China. He now lives in the United States, working as a cartoonist for Voice of America.

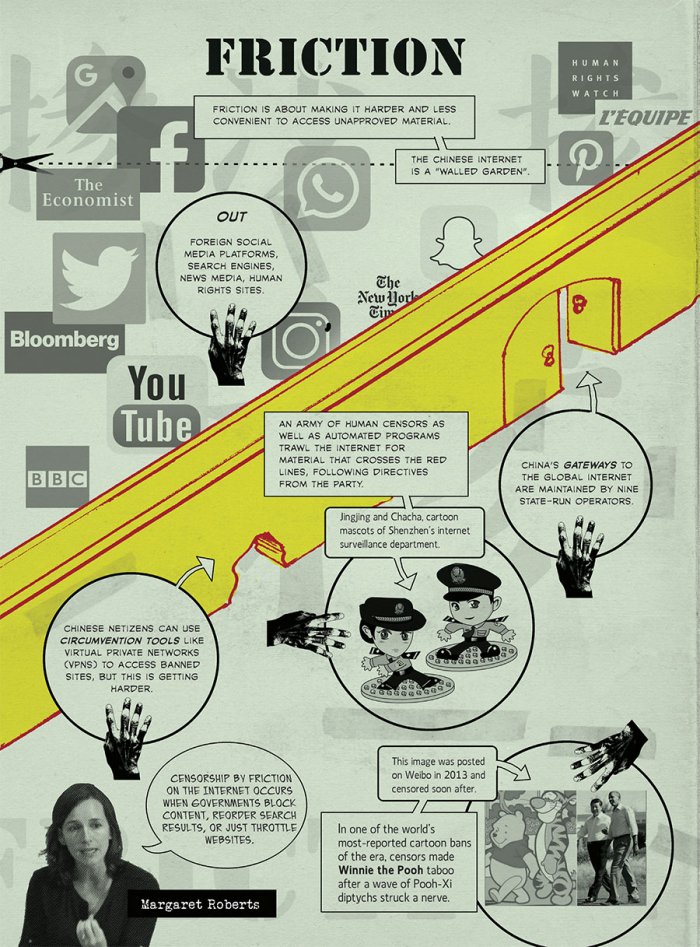

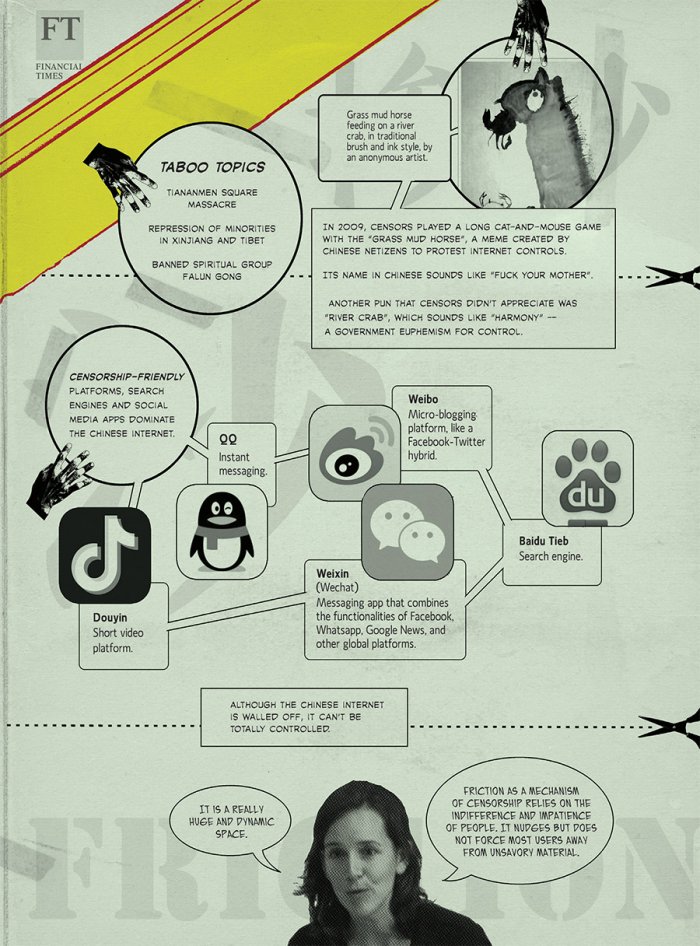

FRICTION

Friction is about making it harder and less convenient to access unapproved material. The Chinese internet is a “walled garden.” Out: Foreign social media platforms, search engines, news media, human rights sites.

An army of human censors as well as automated programs trawl the internet for material that crosses the red lines, following directives from the party. China’s gateway to the global internet is maintained by nine state-run operators. Chinese netizens can use circumvention tools like virtual private networks (VPNs) to access banned sites, but this is getting harder.

In 2009, censors played a long cat-and-mouse game with the “grass mud horse,” a meme created by Chinese netizens to protest internet controls. Its name in Chinese sounds like “fuck your mother.” Another pun that censors didn’t appreciate was “river crab,” which sounds like “harmony” — a government euphemism for control.

Although the Chinese internet is walled off, it can’t be totally controlled.

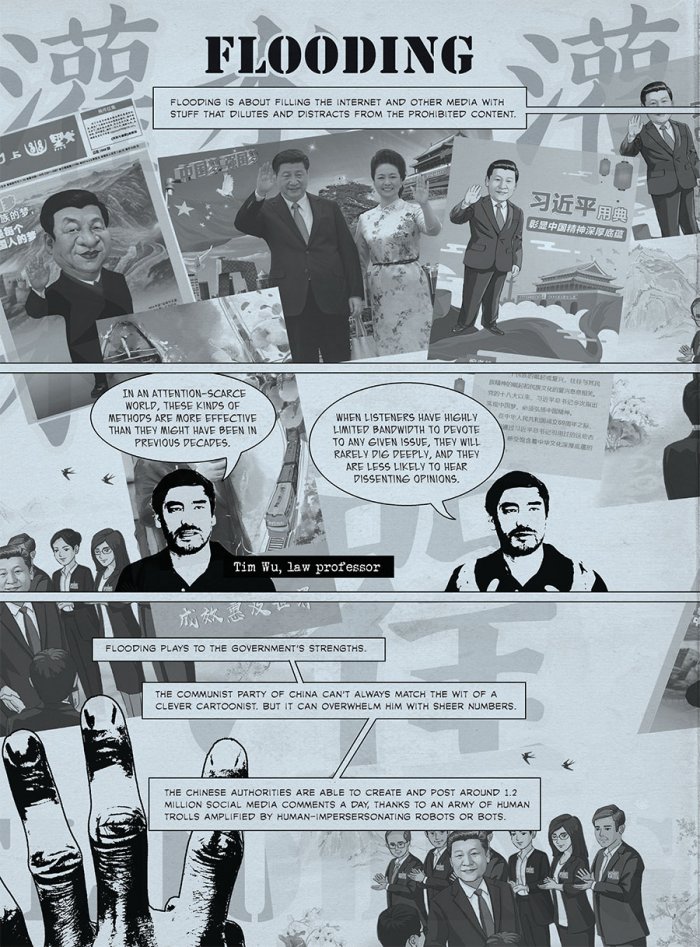

FLOODING

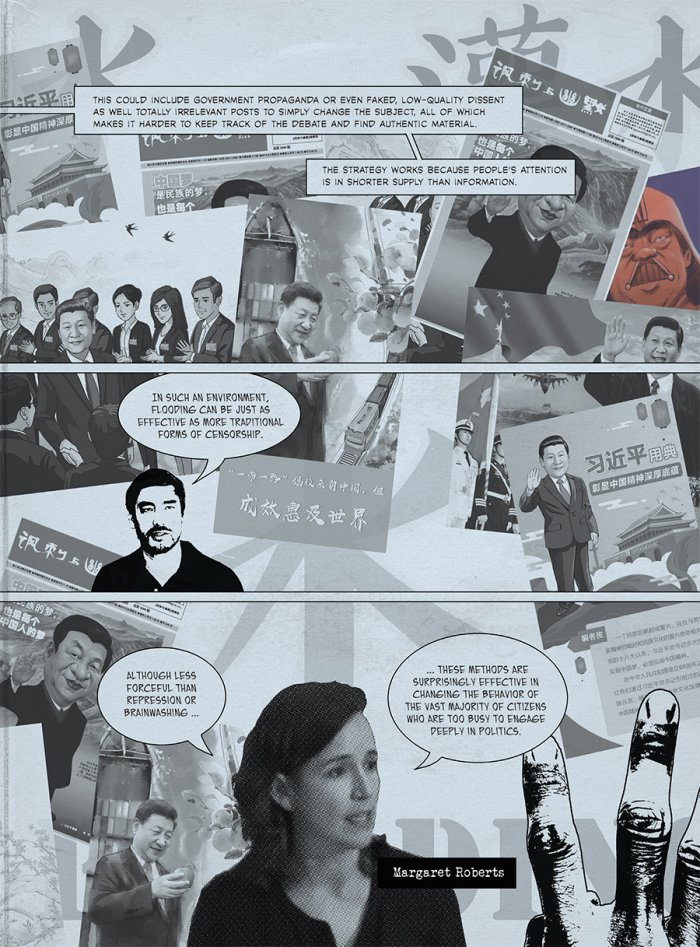

Flooding is about filling the internet and other media with stuff that dilutes and distracts from the prohibited content.

Flooding plays to the government’s strengths. The communist party of China can’t always match the wit of a clever cartoonist. But it can overwhelm him with sheer numbers. The Chinese authorities are able to create and post around 1.2 million social media comments a day, thanks to an army of human trolls amplified by human-impersonating robots or bots.

This could include government propaganda or even faked, low-quality dissent as well as totally irrelevant posts to simply change the subject, all of which makes it harder to keep track of the debate and find authentic material. The strategy works because people’s attention is in shorter supply than information.

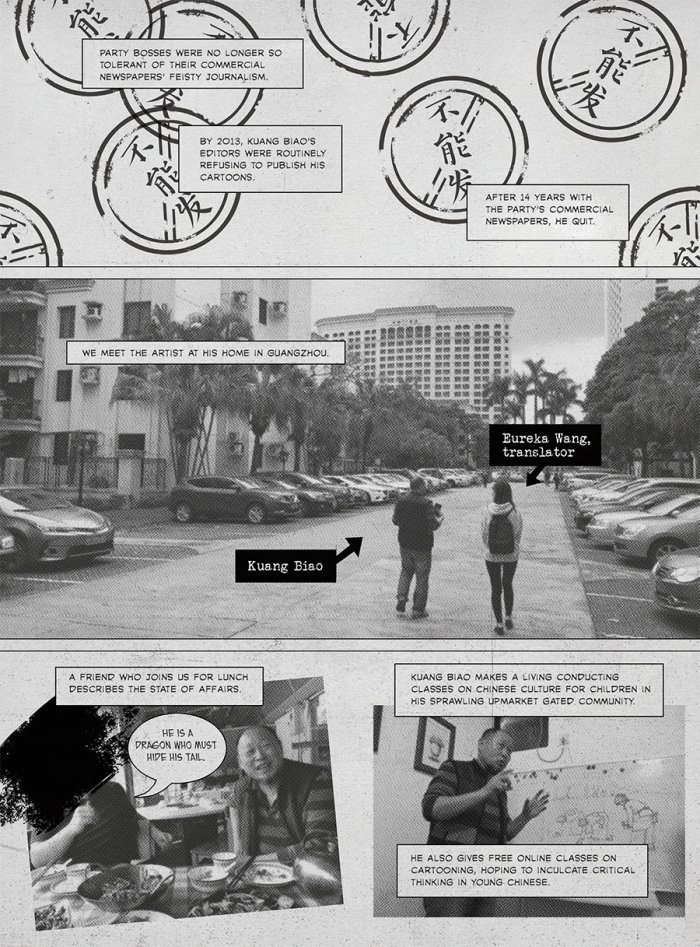

The shifting red lines of Chinese censorship are reflected in the career of Kuang Biao, one of China’s most famous political cartoonists. Kuang is a native of Guangdong Province, whose coastal cities were among the first to benefit from Deng’s economic reforms.

The Guangdong model was associated with more freedom for civil society, trade unions, and media. Kuang’s career as a newspaper cartoonist began at the commercially-oriented New Express, which he joined in 1999. In 2007, he was recruited by another commercial paper, Southern Metropolis Daily.

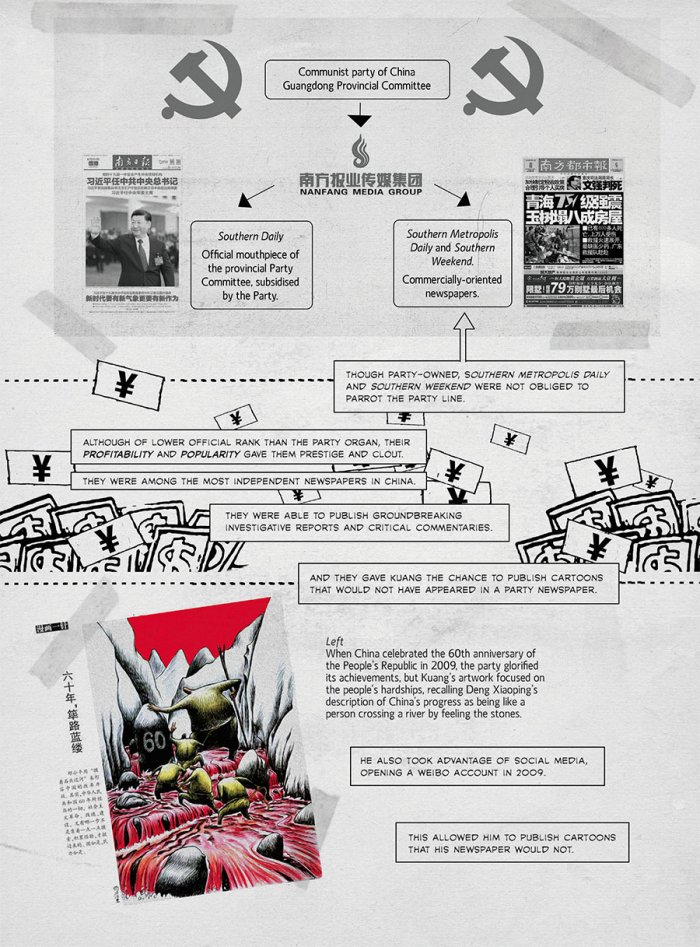

Though party-owned, Southern Metropolis Daily and Southern Weekend were not obliged to parrot the party line. Although of lower official rank than the party organ, their profitability and popularity gave them prestige and clout. They were among the most independent newspapers in China. They were able to publish groundbreaking investigative reports and critical commentaries.

And they gave Kuang the chance to publish cartoons that would not have appeared in a party newspaper. He also took advantage of social media, opening a Weibo account in 2009. This allowed him to publish cartoons that his newspaper would not.

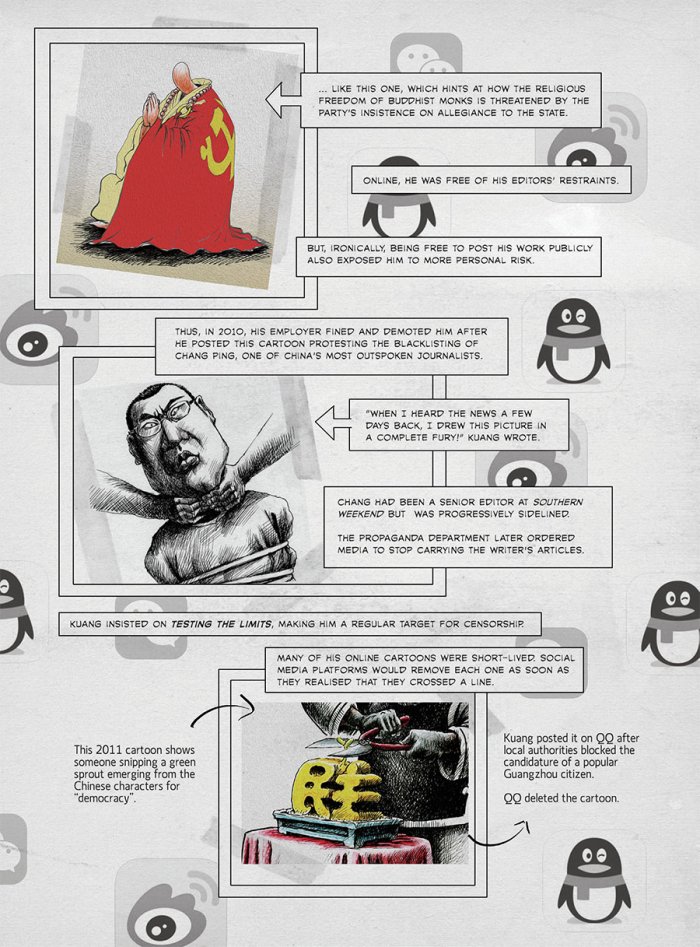

Online, he was free of his editors’ restraints. But, ironically, being free to post his work publicly also exposed him to more personal risk. Thus, in 2010, his employer fined and demoted him after he posted a cartoon protesting the blacklisting of Chang Ping, one of China’s most outspoken journalists.

Chang had been a senior editor at Southern Weekend but was progressively sidelined. The Propaganda Department later ordered media to stop carrying the writer’s articles. Kuang insisted on testing the limits, making him a regular target for censorship. Many of his online cartoons were short-lived. Social media platforms would remove each one as soon as they realized that they crossed a line.

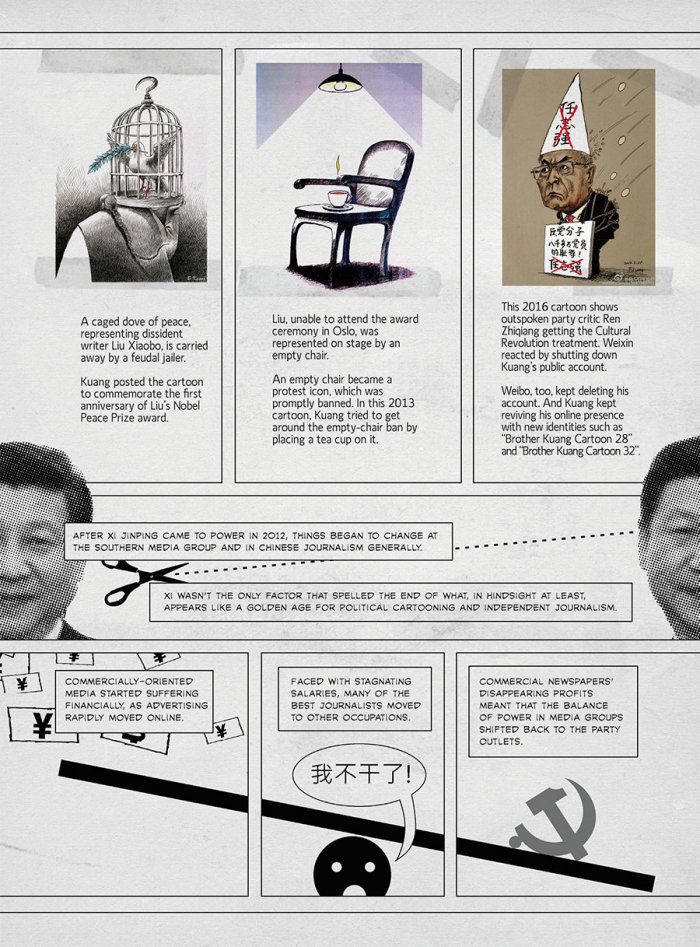

After Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, things began to change at the Southern Media Group and in Chinese journalism generally. Xi wasn’t the only factor that spelled the end of what, in hindsight at least, appears like a golden age for political cartooning and independent journalism.

Commercially-oriented media started suffering financially, as advertising rapidly moved online. Faced with stagnating salaries, many of the best journalists moved to other occupations. Commercial newspapers’ disappearing profits meant that the balance of power in media groups shifted back to the party outlets.

Party bosses were no longer tolerant of their commercial newspapers’ feisty journalism. By 2013, Kuang Biao’s editors were routinely refusing to publish his cartoons. After 14 years with the party’s commercial newspapers, he quit.

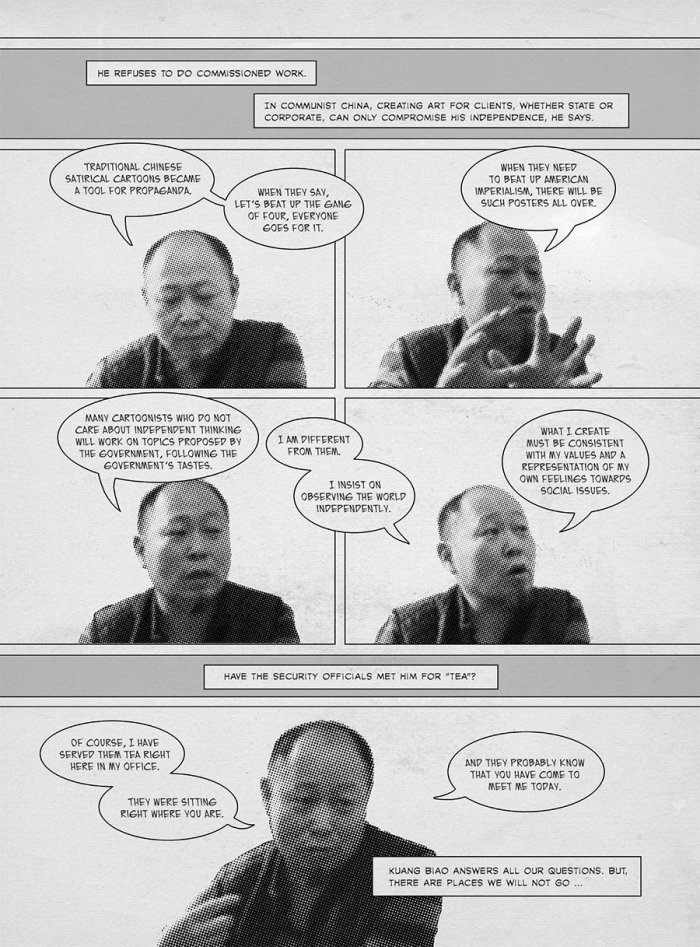

He refused to do commissioned work. In communist China, creating art for clients, whether state or corporate, can only compromise his independence, he says. Have the security officials met him for “tea”?

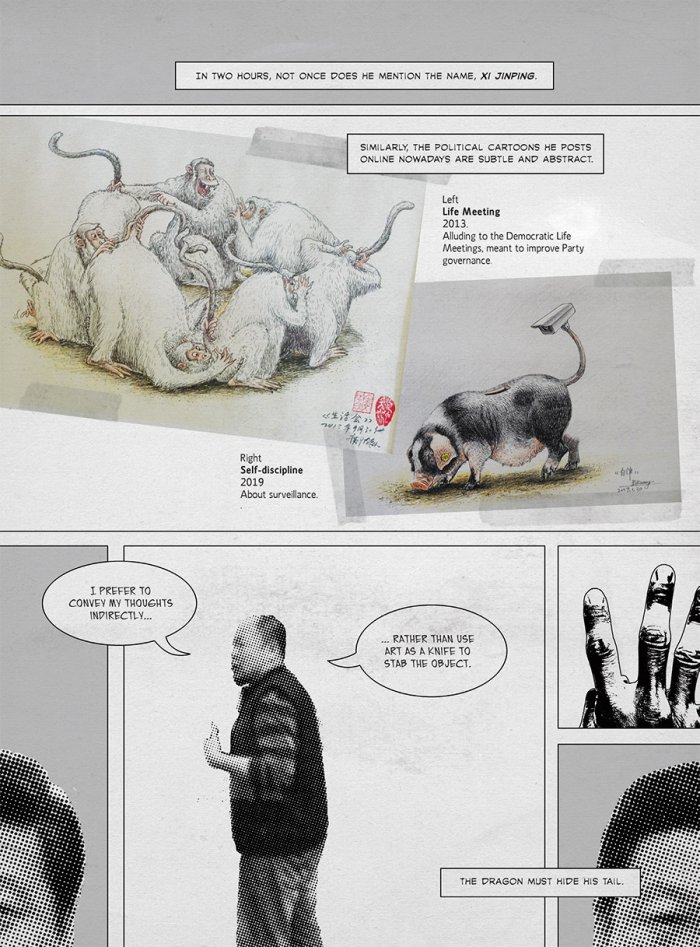

In two hours, not once does he mention the name Xi Jinping. Similarly, the political cartoons he posts online nowadays are subtle and abstract. The dragon must hide his tail.

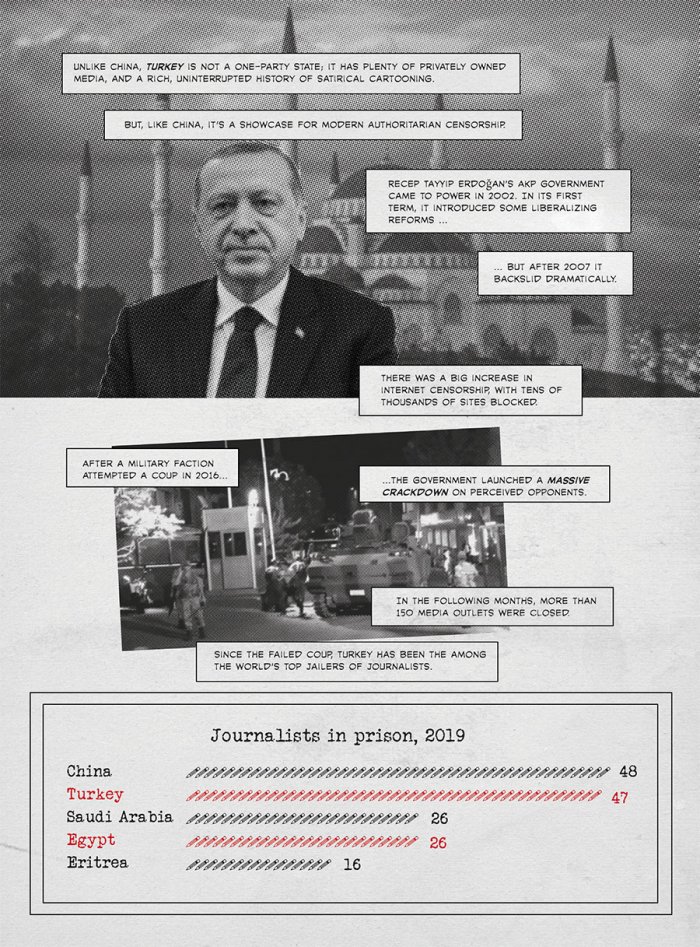

Unlike China, Turkey is not a one-party state; it has plenty of privately owned media, and a rich, uninterrupted history of satirical cartooning. But, like China, it’s a showcase for modern authoritarian censorship.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP government came to power in 2002. In its first term, it introduced some liberalizing reforms, but after 2007 it backslid dramatically.

There was a big increase in internet censorship, with tens of thousands of sites blocked. After a military faction attempted a coup in 2016 the government launched a massive crackdown on perceived opponents. In the following months, more than 150 media outlets were closed. Since the failed coup, Turkey has been among the world’s top jailers of journalists.

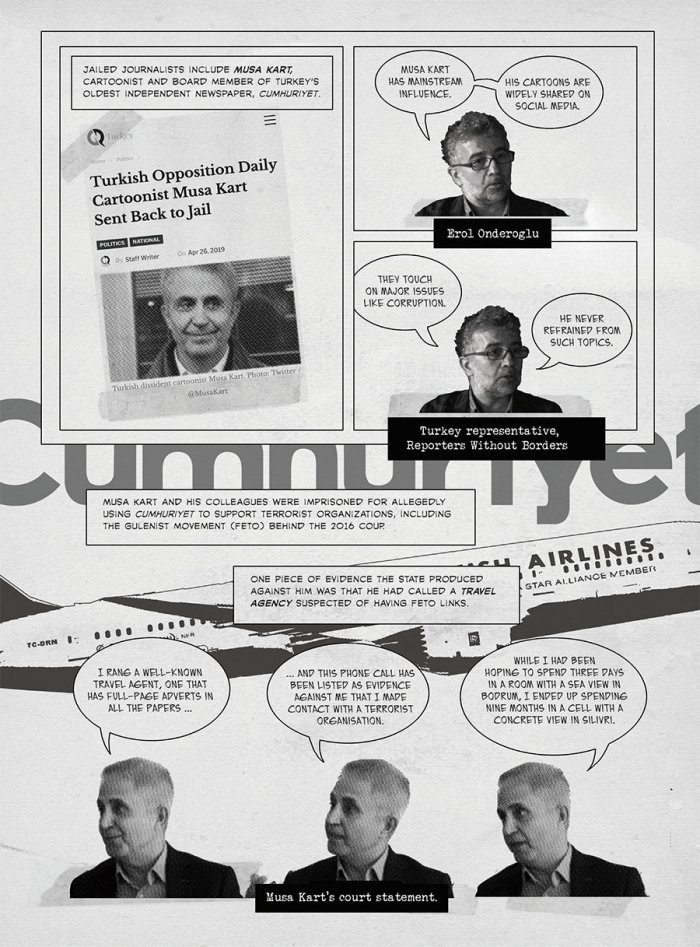

Jailed journalists include Musa Kart, cartoonist and board member of Turkey’s oldest independent newspaper, Cumhuriyet. Musa Kart and his colleagues were imprisoned for allegedly using Cumhuriyet to support terrorist organizations, including the Gülenist Movement (FETÖ) behind the 2016 coup. One piece of evidence the state produced against him was that he had called a travel agency suspected of having FETÖ links.

The charges were filed in the run-up to the April 2017 referendum to turn the country from a parliamentary to a presidential republic, which would greatly enhance Erdoğan’s powers. The timing was no coincidence, Kart told interviewers.

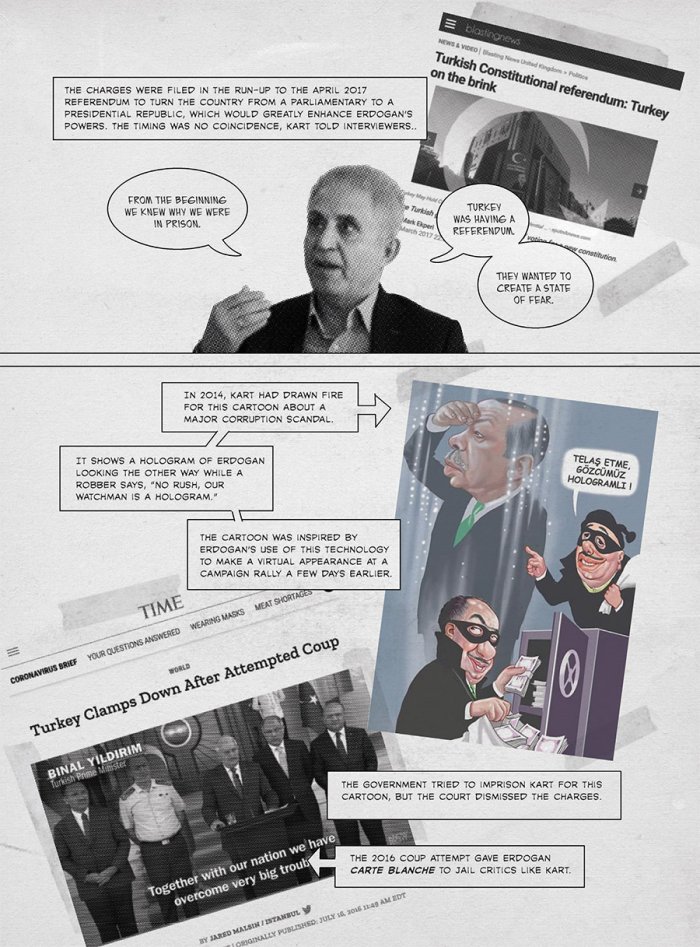

In 2014, Kart had drawn fire for a cartoon about a major corruption scandal. It shows a hologram of Erdoğan looking the other way while a robber says, “No rush, our watchman is a hologram.” The cartoon was inspired by Erdoğan’s use of this technology to make a virtual appearance at a campaign rally a few days earlier.

The government tried to imprison Kart for this cartoon, but the court dismissed the charges. The 2016 coup attempt gave Erdoğan carte blanche to jail critics like Kart.

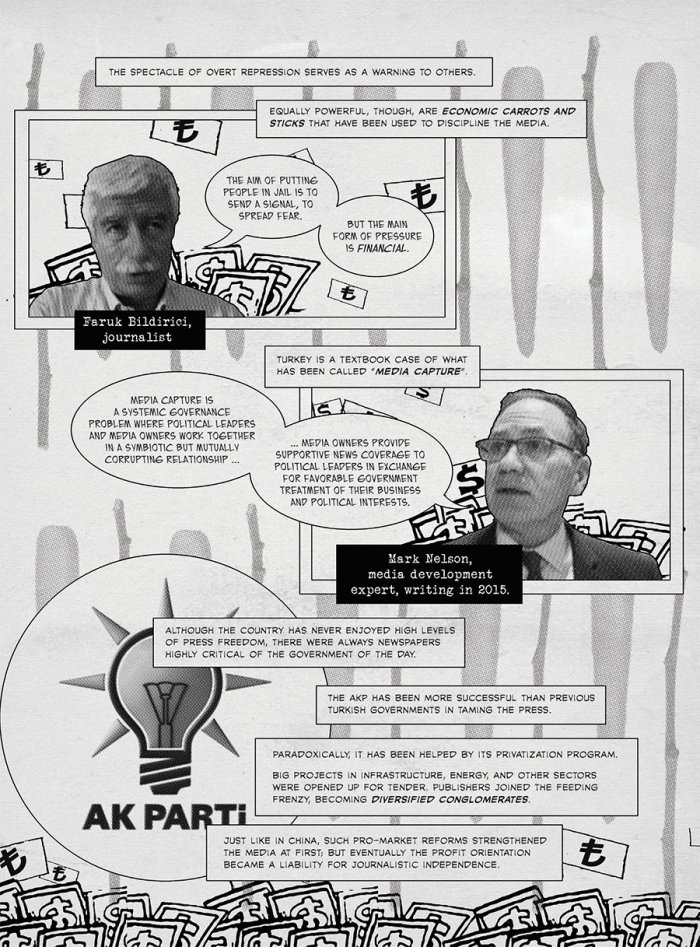

The spectacle of overt repression serves as a warning to others. Equally powerful, though, are economic carrots and sticks that have been used to discipline the media.

Turkey is a textbook case of what has been called “Media Capture.” Although the country has never enjoyed high levels of press freedom, there were always newspapers highly critical of the government of the day. The AKP has been more successful than previous Turkish governments in taming the press.

Paradoxically, it has been helped by its privatization program. Big projects in infrastructure, energy, and other sectors were opened up for tender. Publishers joined the feeding frenzy, becoming diversified conglomerates. Just like in China, such pro-market reforms strengthened the media at first; but eventually the profit orientation became a liability for journalistic independence.

Media owners’ interests in sectors such as mining, energy, construction, and tourism made them reliant on government licensing, contracts, and subsidies, thus exposing them to political blackmail.

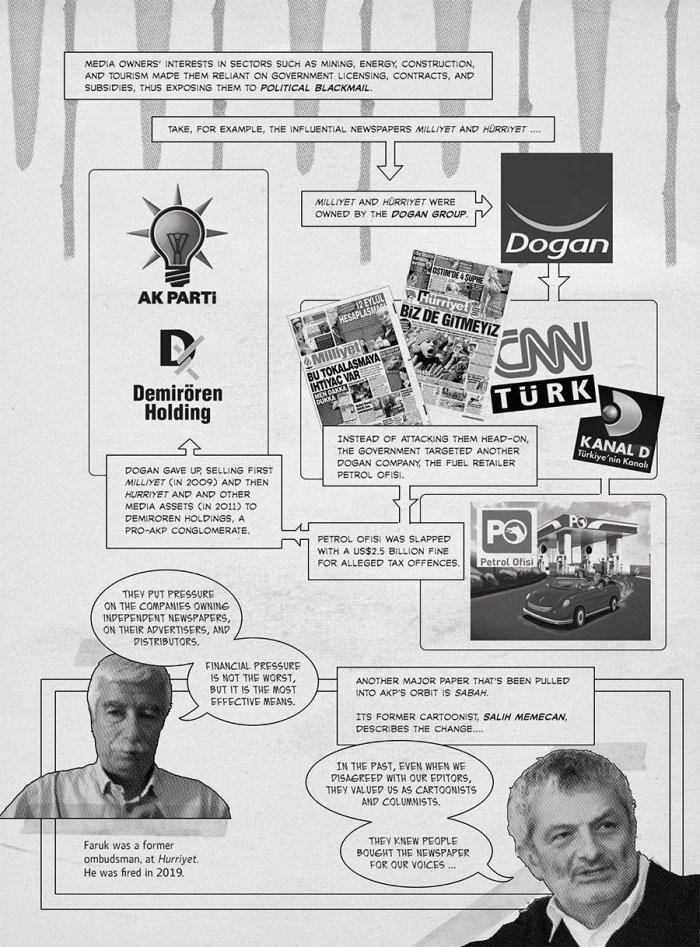

Take, for example, the influential newspapers Milliyet and Hürriyet, which were owned by the Dogan Group. Instead of attacking them head-on, the government targeted another Dogan company, the fuel retailer Petrol Ofisi. Petrol Ofisi was slapped with a $2.5 billion fine for alleged tax offenses. Dogan gave up, selling first Milliyet (in 2009) and then Hürriyet and other media assets (in 2011) to Demiroren Holdings, a pro-AKP conglomerate.

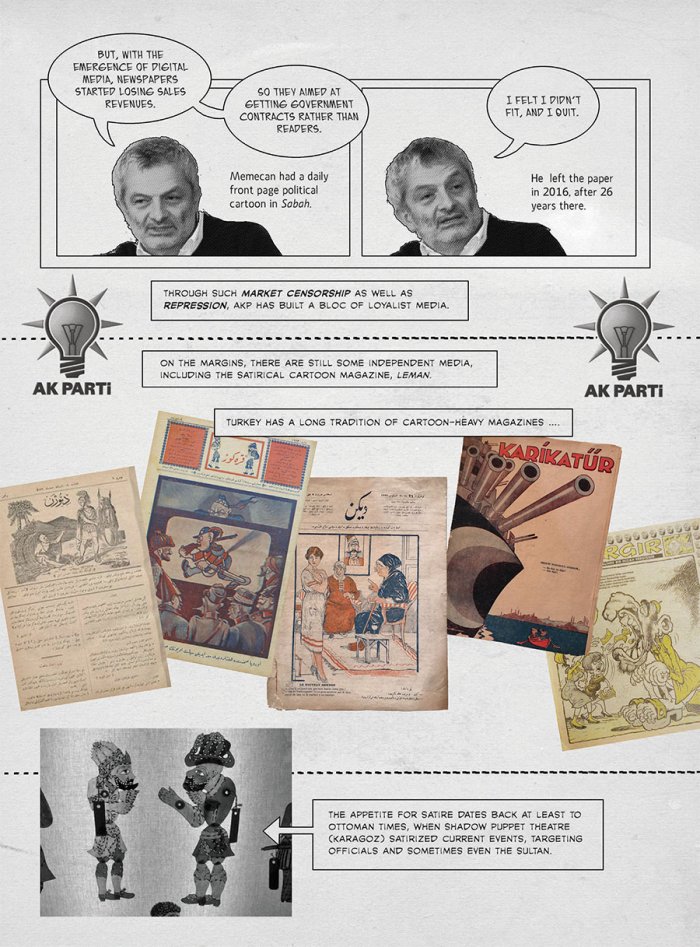

Another major paper that’s been pulled into AKP’s orbit is Sabah. Its former cartoonist, Salih Memecan, describes the change:

In the past, even when we disagreed with our editors, they valued us as cartoonists and columnists. They knew people bought the newspaper for our voices. But, with the emergence of digital media, newspapers started losing sales revenues. So they aimed at getting government contracts, rather than readers. I felt I didn’t fit, so I quit.

Through such market censorship as well as repression, AKP has built a bloc of loyalist media.

On the margins, there are still some independent media, including the satirical cartoon magazine, Leman. Turkey has a long tradition of cartoon-heavy magazines. The appetite for satire dates back at least to Ottoman times, when shadow puppet theater (Karagoz) satirized current events, targeting officials and sometimes even the Sultan.

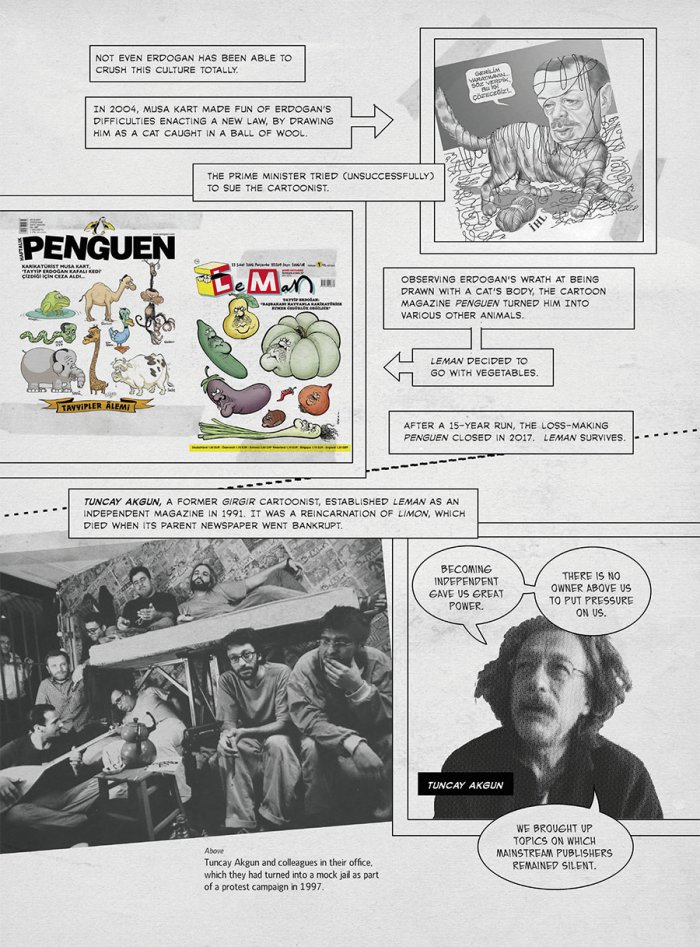

Not even Erdoğan has been able to crush this culture totally. In 2004, Musa Kart made fun of Erdoğan’s difficulties enacting a new law, by drawing him as a cat caught in a ball of wool. The prime minister tried (unsuccessfully) to sue the cartoonist.

Observing Erdoğan’s wrap at being drawn with a cat’s body, the cartoon magazine Penguen turned him into other animals. Leman decided to go with vegetables. After a 15-year run, the loss-making Penguen closed in 2017. Leman survives.

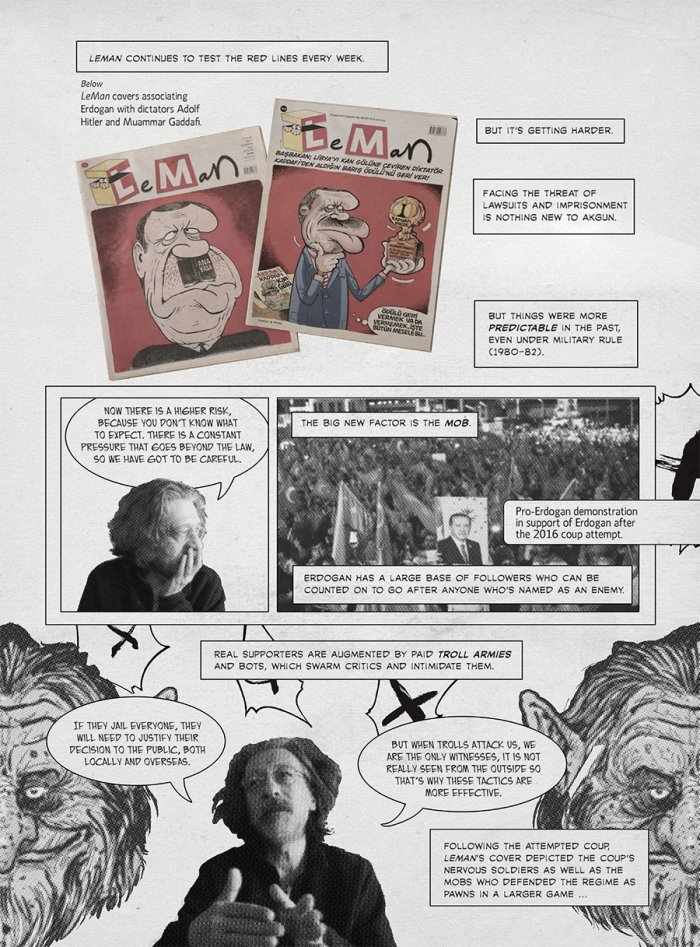

Tuncay Akgün, a former Girgir cartoonist, established Leman as an independent magazine in 1991. It was a reincarnation of Limon, which died when its parent newspaper went bankrupt.

Leman continues to test the red lines every week. But it’s getting harder. Facing the threat of lawsuits and imprisonment is nothing new to Akgun. But things were more predictable in the past, even under military rule (1980–82).

The big new factor is the mob. Erdogan has a large base of followers who can be counted on to go after anyone who’s named as an enemy. Real supporters are augmented by paid troll armies and bots, which swarm critics and intimidate them.

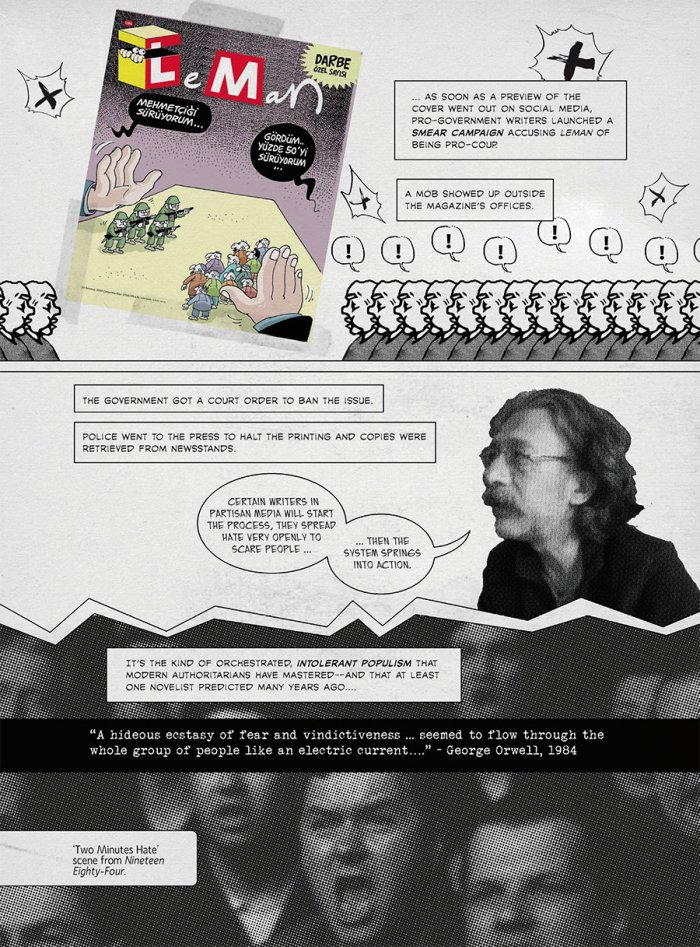

Following the attempted coup, Leman’s cover depicted the coup’s nervous soldiers as well as the mobs who defended the regime as pawns in a larger game.

As soon as a preview of the cover went out on social media, pro-government writers launched a smear campaign accusing Leman of being pro-coup. A mob showed up outside the magazine’s offices.

The government got a court order to ban the issue. Police went to the press to halt the printing and copies were retrieved from newsstands. It’s the kind of orchestrated, intolerant populism that modern authoritarians have mastered — and that at last one novelist predicted many years ago.

“… Big Brother seemed to tower up, an invincible, fearless protector… full of power and mysterious calm, and so vast that it almost filled up the screen. Nobody heard what Big Brother was saying.

It was merely a few words of encouragement, the sort of words that are uttered in the din of battle, not distinguishable individually but restoring confidence by the fact of being spoken.”

—George Orwell, 1984

Cherian George is Professor of Media Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University’s School of Communication. A former journalist, he is the author of “Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and Its Threat to Democracy.”

Sonny Liew is a celebrated cartoonist and illustrator and the author of “The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye,” a New York Times bestseller, which received three Eisner Awards and the Singapore Literature Prize.