'Messengers of Goodwill': America’s Tokens of Friendship and Power

In spring 1927, an American teacher named Lillie Newton Douglas traveled from Los Angeles to Tokyo to initiate an exchange of visual materials between Californian and Japanese schools. Sent by the Visual Education Department of the Los Angeles school system, which was at the forefront of a growing movement to teach internationalism to young people, Douglas’s mission was to make arrangements with the Japanese to exchange “student-made school work, handicrafts, drawings and objects” to illustrate the “home life, school life, and play life of the two countries.” Conducting such an exchange with Japan was important, educators believed, to counter the anti-Asian rhetoric that had led to the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, which barred Asians from immigrating to the United States.

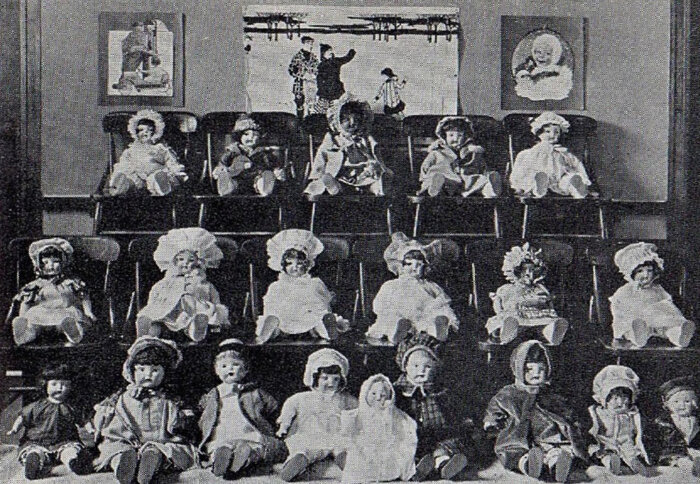

Yet while she was in Japan, Douglas encountered a similar program that was already underway on the ground — involving not an exchange of visual aids but rather a shipment of 13,000 dolls. Dubbed “messengers of goodwill,” the American dolls had been outfitted by thousands of schools, scout troops, and churches in the U.S., and sent by steamship to Japan under the auspices of the Committee on World Friendship Among Children (CWFC), a nonprofit peace education organization based in New York City and supported by the Federal Council of Churches, an ecumenical association of Protestant denominations.

While its 1927 shipment of friendship dolls to Japan was the first and most widely publicized of its projects, the CWFC went on to conduct several more campaigns on an even larger scale, including sending 30,000 schoolbags to Mexico in 1928, 28,000 treasure chests to the U.S.-occupied Philippines from 1929 to 1930, 6,000 treasure chests to U.S.-occupied Puerto Rico in 1931, and 20,000 paper albums, or “friendship folios,” to China in 1932. The CWFC members selected the destinations and token objects (also referred to as “symbols”) based on their assessment of which peoples were most in need of “an assurance of our friendly interest and our goodwill,” and which objects would carry “special meaning” for the children of that place. Children were encouraged to raise small amounts of money to order the gifts and then personalize them with their own “goodwill messages” and accessories before sending them to the organization’s headquarters for shipment abroad.

Though the tokens were welcomed and enjoyed by educators and children alike, they also carried a subtext of American superiority and power.

The CWFC projects offer insight into how interwar missionaries and peace educators conceived of toys and material objects as potent instruments for fostering international understanding. Part of a wave of peace-building and cultural exchange initiatives that emerged in the U.S. and Europe in the wake of World War I, the projects advanced a belief that teaching younger generations to communicate with each other across borders could engender international amity and prevent future conflicts. When planning the doll exchange in 1926, for example, the CWFC agreed in meetings that “the dolls are not to be sent as gifts, with the idea of giving something to Japan, but they are to be representatives of the children of America, bearing messages of friendship and goodwill.”

To play up the notion of the dolls as living messengers rather than dormant objects or playthings, the CWFC launched a public relations campaign — “Say It with Dolls” — to portray the dolls as pint-size emissaries of the United States. After securing a miniature passport, visa, and travel ticket for their dolls from the CWFC headquarters (temporarily named the “Doll Travel Bureau”), children were instructed to creatively outfit their dolls with regional clothing and luggage, attach a written “message of goodwill” and return address signed by each child, and involve their communities in hosting “a ‘farewell party’ to say ‘goodbye’ and to wish the doll ‘bon voyage’ as it starts its long journey and success in delivering the message.”

Though subsequent CWFC projects featured nonanthropomorphic objects, such as schoolbags, folios, and treasure chests filled with trinkets, the program officials described them all in various turns as “ambassadors” or avatars for the children who sent them as well as vessels of their heartfelt goodwill. In preparation for the Friendship Project to Mexico in 1928, for instance, the CWFC chose schoolbags as the symbol of friendship “to carry the good wishes of the children of America to the children of Mexico.” The handsome bags, manufactured in the United States with Fabrikoid, a synthetic leather used in automobile upholstery, featured an embossed message of “Goodwill Greetings” in Spanish and English on the exterior, framing a playful image of children holding hands. The notion that material goods could ferry sentiments of goodwill across oceans and borders was the organizing principle behind each CWFC project, and according to its reports, was echoed back by the officials and children who received them abroad.

Elaborate reception ceremonies for the CWFC tokens were presided over by dignitaries in each country, including the imperial family in Japan, the president of Mexico, and ambassadors and educational authorities. The participation of high-level officials in these events lent legitimacy to the notion that token exchanges among children were effectively an extension of state diplomacy. It was an idea that would later gain the full backing of the U.S. government during the Cold War, as “citizen diplomacy” initiatives such as pen pal and “sister city” programs, facilitated by the People-to-People program formed by the Eisenhower administration, instrumentalized cultural exchange as a means of extending American influence and soft power around the globe.

When children received the CWFC dolls and other tokens, many used the attached return addresses to send letters of thanks to the American senders, initiating countless correspondences and pen friendships. Observers noted that for the young receivers, the significance of the materials lay not only in their novelty or intrinsic value as playthings but also in the idea that they had traveled great distances and with friendly intentions from the children of America.

In one message of gratitude to the CWFC reported by the New York Herald Tribune, Moisés Saenz, assistant minister of education in Mexico, described the lengthy journey made by a single CWFC schoolbag to reach the remote Tiburón Island. There, indigenous children reacted with such enthusiasm that they immediately worked to reciprocate the gesture using the meager materials they had on hand:

The bag was carried eighty miles across desert by auto, then by car, horseback and rowboat to Tiburón Island, “then on the back of an Indian for several miles to the Indian camp, where the bag was opened and the ‘good will’ things distributed to the Seri children, who were made very happy to receive them, as they rarely receive any gifts, except persecution and ill will. These primitive people, wild as coyotes, appreciate kindness, generosity and thoughtfulness. A number of children immediately went along the shore of the gulf and one hundred feet distant and in half an hour returned with lovely shells washed up by the surf. These are sent [to] you as a small token of appreciation from one of the wildest tribes in America.”

Such accounts testified to the symbolic power of traveling objects — whether elaborate schoolbags or humble seashells — to build a palpable sense of connection among far-flung children. But Saenz’s comments about the Seri children being “primitive” and “wild” people in need of the “kindness” emblematized by the American schoolbag also highlight the salience of colonialism and racism in such programs.

By mobilizing young Americans to send toys and supplies to children abroad and in U.S.-occupied territories, the CWFC worked in alignment with the Junior Red Cross, missionary networks, and other service organizations to promote sanitation, education, and economic growth in the “developing” world. As historian Julia Irwin has argued, the economic as well as material aid dispensed by such organizations became a key mechanism through which Americans interacted with the wider world and understood their country’s role in international relations in the 20th century. Several CWFC campaigns encouraged children to pair their token gifts with basic hygienic and school supplies, such as drinking cups and soap in the Mexican schoolbags, books in the treasure chests to the Philippines, and vouchers to sponsor lunches from a local charity in Puerto Rico to accompany the chests that were sent there.

From one campaign to the next, by coupling their messages of goodwill with specific materials intended to promote hygiene, literacy, and nutrition in the receiving countries, the CWFC Friendship Projects seemed intent on conflating a peer relationship of friendship with a paternal relationship of providing aid and developmental assistance. Despite the committee’s professed attempts to strip its projects of any “missionary flavor,” and package the outgoing materials as gestures of equitable friendship rather than gifts or aid, their fraught contents and mass, unsolicited shipment overseas conveyed a subtext about the economic might of the United States, and presumed neediness of recipient nations and territories for “assurance” of its generosity along with specific modern products and supplies.

The committee decided to include instructions in the official literature that stated that the dolls should “look like attractive and typical American girls,” which, they concluded, would “indirectly suggest that the dolls should be white.”

Indeed, the CWFC encouraged American children to prepare their tokens in a manner consistent with the ideology that the United States had a responsibility to help or at least to model modernity for the people of other industrializing nations. Children sending dolls to Japan, for example, were instructed that their dolls “should be new and should be carefully dressed in every detail, since they will serve as models in a country where habits and customs are undergoing rapid changes.”

Tellingly, in order to model modernity for Japan, the CWFC decided that it was important for the American dolls to be white. In its internal discussions about whether to allow children to send “colored” dolls, the committee decided to include instructions in the official literature that stated that the dolls should “look like attractive and typical American girls,” which, they concluded, would “indirectly suggest that the dolls should be white.” Such blunt assessments underscore the extent to which white reformers’ efforts to teach “world friendship” were infused with the ideology of white supremacy.

From pen pal programs to exchanges of goodwill tokens, advocates of peace education commonly excluded African American and other children of color from both participation and representation in their programs, and quietly reinscribed notions of white racial superiority into activities that professed to teach about the importance of eradicating prejudice and building “friendship” among all peoples.

Indeed, adopting the terminology of “friendship” made it possible for Americans to avoid discussions of equality. Reflecting the image of the U.S. as a rising and benevolent world power, the CWFC literature depicted the receiving countries as grateful to the point of being overwhelmed by the influx of generosity from America.

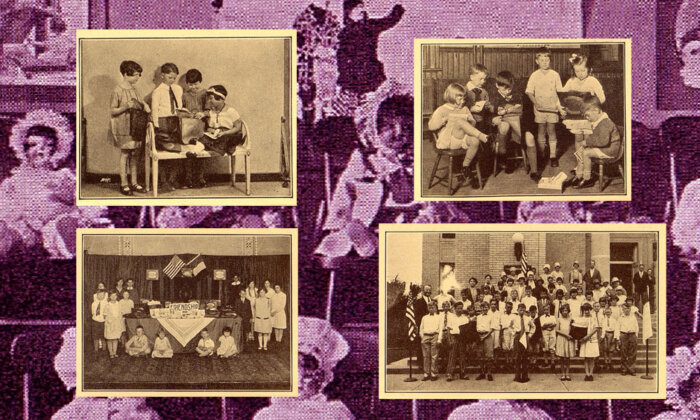

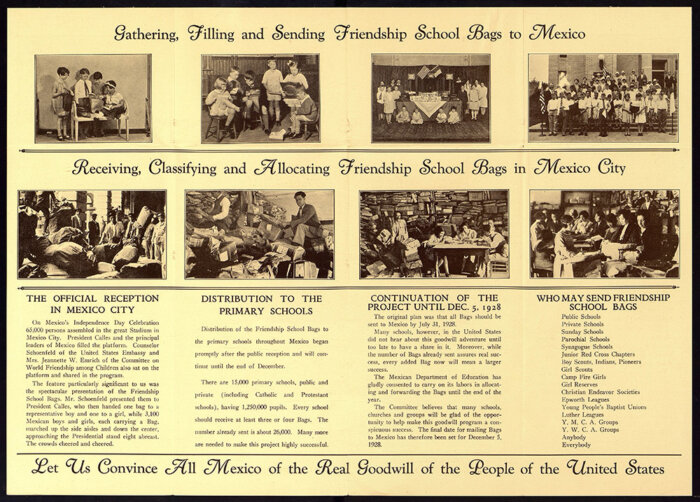

A 1928 pamphlet publicizing the success of the Mexico project, for example, offered a stark visual contrast between images of American children preparing the schoolbags for shipment and the Mexican educational officials receiving them. In the top row, photographs of white American children showcased the orderly assembly and ceremonial send-off of schoolbags from the United States. In the bottom row, in contrast, Mexican educational officials were depicted in a chaotic scene — captioned, “Receiving, Classifying and Allocating Friendship School Bags in Mexico City” — in which they appeared to be swamped by mountains of schoolbags delivered from America.

The disorderly abundance of the schoolbags, heaped floor to ceiling in a facility in Mexico City, simultaneously suggested the tremendous and organized generosity of the United States, and lack of infrastructure in Mexico to adequately handle and distribute such aid. While the pamphlet urged the American readers, “Let us convince all Mexico of the real goodwill of the people of the United States,” the project seemed to be less intent on commemorating equitable friendship with the people of Mexico than it was about reasserting the image of the United States as a land of order and material abundance, and the dominant figure in U.S.-Mexican relations. As historian Elena Jackson Albarrán has written, the shipment merely reinforced the stereotype of “Mexico as infantile, Indian land requiring U.S. charity to transform its residents into productive citizens.”

Adopting the terminology of “friendship” made it possible for Americans to avoid discussions of equality.

Despite the CWFC’s aim to distribute tangible symbols of American goodwill around the globe, the material nature of its exchanges indirectly foregrounded the socioeconomic, technological, and infrastructural inequalities that existed between the United States, its occupied territories, and other countries. Some of the recipient nations and territories responded to the American gifts by sending their own “goodwill greetings” in return. These gifts — which included 58 dolls from Japan, 49 handicraft exhibits from Mexico, and a children’s radio address from the Philippines — provided an opportunity for the recipient countries to speak back to their U.S. counterparts and gently correct what they perceived to be American misconceptions about them.

In Welcome to the Doll Messengers, a 1927 booklet published by the Committee on International Friendship among Children in Japan, a group formed in response to the CWFC doll project, the Japanese thanked the American children for the shipment of friendship dolls. Writing in the voice of the Japanese dolls it would send in return, the Committee utilized the same concept of the doll as messenger to convey a rejoinder that subtly asserted Japan’s modernity and status as a comparable industrial power:

Do you know what kind of country Japan is? We are quite sure that you will say, “yes,” but we . . . wonder if you really know the modern Japan. . . . We wonder what your doll-messengers said when they arrived in Yokohama after their long voyage across the Pacific. Perhaps they talked together in amazement and said: “Why, is Japan such an enlightened country as this? Before we left America we heard many things about Japan, but we did not believe that Japan was so far advanced in civilization. We were talking of the ancient Japan of Perry and his followers, and imagined it to be like the island empire of fairy stories. But this new country is like America. We shall never be homesick here.

The passage highlights how countries on the receiving end of the United States’ goodwill used tokens to convey their own messages and represent themselves on their own terms, reciprocating a gesture of friendship, on the one hand, while demonstrating their own national and cultural wealth, identity, and power, on the other. It also testifies to the larger point that the CWFC’s token objects could be interpreted not simply as vessels of goodwill but also as oblique reminders of what the United States perceived to be its advanced socioeconomic state in comparison to other countries.

Though the tokens were welcomed and enjoyed by educators and children alike — and seemed successful in generating meaningful moments of intercultural connection and correspondence between children in the United States and other countries — they also carried a subtext of American superiority and power that reinforced the notion of the United States not as a friend or equal but instead a magnanimous “global parent charged with bringing up a family of nations,” to quote historian Sara Fieldston.

Mediated intercultural exchanges in schools were, by many accounts, deeply meaningful and memorable lessons. They gave scores of American students a personalized perspective on different cultures through unprecedentedly direct communications with far-flung peers. But while these practices were widely celebrated for breaking down stereotypes and building mutual understanding, their message of youthful amity was frequently undercut by their entanglement with larger nationalist and imperialist ideologies and policies.

Paradoxically, the activity of crafting and sending messages abroad in an expression of international friendship often doubled as an opportunity for white American children to rehearse and reinforce narratives about their own cultural superiority and national exceptionalism. Openly embraced as a form of junior diplomacy, such exchanges frequently mirrored the dominant geopolitical priorities of the United States, and blurred the lines between equitable practices of exchange and paternalistic policies of Americans providing aid, assistance, and advice to the rest of the world.

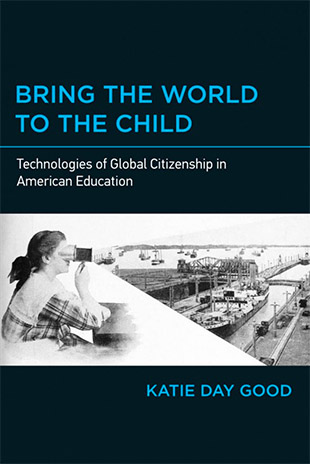

Katie Day Good is Assistant Professor in the Department of Media, Journalism, and Film at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and the author of “Bring the World to the Child,” from which this article is adapted.