A Brief History of Secret Communication Methods, From Invisible Ink to Tattooed Heads

For centuries, secrecy was the backbone of espionage and of communications between case officers and agents. Despite the dangers, secret communication is at the heart of espionage operations and essential for spy work: Not only does it keep the agent and case officer connected but it allows information to be passed on from agent to headquarters.

The text that follows is excerpted from a chapter in Kristie Macrakis’s book “Espionage: A Concise History,” in which Macrakis outlines the major components of secret communication methods used by agents — from concealment and dead drops to photography and microdots. The focus here is on ancient trends and methods, such as employing invisible ink and concealing messages in animal carcasses, some of which are still used today.

Kristie Macrakis was Professor of History in the School of History and Sociology at Georgia Tech and the author of many books, including “Seduced by Secrets” (Cambridge University Press), “Prisoners, Lovers, and Spies” (Yale University Press), and “Nothing Is Beyond Our Reach” (Georgetown University Press). She passed away in November 2022.

–The Editors

Spies, or scouts, have had to communicate secretly since time immemorial. In ancient Greece, Histiaeus, the ruler of Miletus, shaved a slave’s head, tattooed it with a message, and waited for the hair to grow back. He then sent the messenger on the long journey from Persia to Greece to urge revolt. Upon arrival, the messenger’s head was shaved again to read the message.

It is not only the modern reader who will balk at the amount of time it took the message to reach its recipient. In the 17th century, John Wilkins, author of “Mercury; or, the Secret and Swift Messenger,” commented on the “strange shifts the ancients were put unto, for want of skill” and outlined the superior methods of communicating of his own time. He described communicating without a messenger using fire and signs; inanimate media like bullets and arrows; men, animals, birds, sounds, or angels to communicate with someone in a dungeon or besieged city or hundreds of miles away. Of course, even Wilkins’s methods seem impractical and slow to a reader living in the digital age in which communications can travel to the other side of the globe through satellites or fiberoptic cables almost instantaneously.

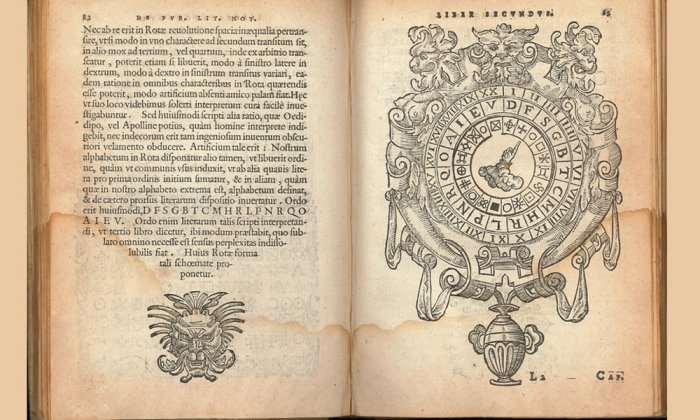

One thing that has not changed since the Renaissance is an obsession with secrecy when it comes to the methods of espionage. Giambattista della Porta, a renaissance man in every way, was a natural philosopher whose work spanned math, optics, alchemy, astrology, physiognomy, memory, agriculture, and cryptography. In his best seller, “Natural Magic,” as well as his influential and encyclopedic book on cryptography, “De furtivis literarum notis,” he searched for the secrets of nature while telling readers that the secrets of cryptography and invisible ink should be “concealed” for “great men” and “princes.” As one of the “professors of secrets,” della Porta also founded an academy of secrets.

It was during the Elizabethan period of secrecy and intrigue that the elements of modern espionage developed. Spies at court and diplomats abroad were recruited to warn of invasion and maintain power at home in the battle between Protestants and Catholics. Queen Elizabeth’s interest in, and appreciation of, espionage is reflected in the resplendent dress immortalized in a famous portrait by Isaac Oliver. In it, Queen Elizabeth’s gown is covered with eyes and ears to symbolize the state’s interest in spying. Francis Walsingham, her spy master, had eyes and ears throughout England and abroad.

It was during the Elizabethan period of secrecy and intrigue that the elements of modern espionage developed.

One of Walsingham’s most celebrated successes was catching Mary, Queen of Scots, a Catholic, in the act of plotting with her supporters to overthrow Queen Elizabeth, a Protestant. Elizabeth had placed Mary under house arrest in various castles and manors out of fear that she might try to overthrow her government and install Catholics. During the early years, Mary could leave the premises and communicate with her supporters. Later, however, Elizabeth cut off Mary’s contact with the outside world. Even so, Mary wrote secret letters in cipher or invisible ink and hid them in slippers or mirrors. She handed the letters to a friendly jailer who passed them on to a courier. But Walsingham soon began to intercept all the letters and pass them to his chief cryptographer. When Walsingham uncovered a plot to murder Elizabeth, Mary was moved into Chartley, an uncomfortable stone manor house surrounded by a moat. Her new jailer was a tough Puritan who placed her under constant, strict observation. It was almost impossible to communicate with Mary from the outside until one of her supporters came up with an ingenious communication system.

Gilbert Gifford, a young blue-eyed Catholic boy, proposed using beer barrels to pass on secrets. In the 16th century, beer, light in alcoholic content, was almost a substitute for water. Chartley did not have its own brewing facilities and had to bring in beer for the household. The Catholic brewer agreed to pass on secret enciphered letters written in invisible ink by placing them in a waterproof box stuffed through the bunghole of the beer barrel; the box would then float on the beer. Unfortunately, although the Catholic brewer was supportive of Mary, he was bribed by Walsingham. Before inserting the letters into the barrels, the brewer gave them to Walsingham, who had his master seal lifter open them. After he read the letters, his assistant resealed them and passed them on.

As if that weren’t bad enough, Gifford, the beer barrel courier, then became a double agent and acquired information about a plot to invade England, murder Elizabeth, and place Mary on the throne. The plan was spearheaded by Anthony Babington, who had assembled 13 co-conspirators. Babington proposed that six conspirators assassinate Elizabeth. Because their names were not mentioned in the intercepted message, Walsingham’s codebreaker forged a postscript asking for their names, which were then smuggled to Mary via the beer barrel express. Since the ciphers were simple nomenclatures — letters of the alphabet were replaced by numbers, symbols, or Greek letters — Walsingham’s codebreaker quickly deciphered the missives and uncovered the names of the conspirators: They were tortured, disemboweled, and then hanged. Mary was put on trial and beheaded. Her only friend at the end was her small dog, who emerged from her blood-stained petticoat and lay between her shoulders and her decapitated head.

Mary was not the first or the last person to lose her life because of intercepted communications. Although not known when they were convicted, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg’s communications with Moscow had been intercepted, the codes cracked, and the messages read before the Rosenbergs were sent to the electric chair.

More common, of course, was the interception of communication that led to the capture and imprisonment of a spy. Whether a spy is killed or imprisoned after being caught communicating, the fact remains that communicating is dangerous — but it is also at the heart of operations. Spies need to collect information, copy it, hide it, and pass it on secretly. They also need to communicate with their handlers about future meetings, danger signals, and instructions.

Concealing the content of a message via cipher can be insufficient; for additional security, the physical message must also be hidden. This is also a very old practice, including using dead animals as hiding places. When Harpagos, a sixth-century Median general, wanted to send a secret message to Cyrus, the king of neighboring Persia, where the roads were patrolled by guards, he slit open the belly of a hare to hide the secret message urging revolt against the Median empire. Harpagos then sewed up the incision and handed the hare to a trusted servant in a hunting net. After the servant, disguised as a hunter, arrived in Persia and reopened the hare’s belly, Cyrus looked inside and found the scroll. The ancients did not seem to mind the stench that the dead hare must have emitted by the time it reached its destination.

The CIA’s Office of Technical Services created fake rubber guts that spilled out of the dead animal.

If we fast forward to the 20th century, it turns out the CIA also used animal carcasses as hiding places. Dead pigeons and rats were favorite animals. After the animals were killed, they were gutted and treated to create a space inside the chest or stomach area. Some animals were freeze-dried or vacuum-packed in tin cans, thus solving the stinky problem of decay. Secret spy gear, money, documents, or instructions were then wrapped in aluminum foil before being placed in the artificial cavity. Then the animal was stitched up and placed on the side of a road. The CIA’s Office of Technical Services also created fake rubber guts that spilled out of the dead animal. To deter hungry scavengers from picking up the dead animals, operators often sprinkled them with Tabasco sauce.

Imagination is the limit when it comes to devising effective hiding places. During World War II, the Germans used a microdot, a tiny miniaturized photograph the size of the period at the end of this sentence, to communicate with agents. Agents hid microdots on a finger or under a toenail; in tie linings, jacket linings, cuffs, collars, shoulder pads, and seams; in suitcase locks, clasps, and handles; on the frames or lenses of glasses; under stones in jewelry; inside book bindings, split postcards, and the gummed flaps of envelopes; in razor blades and wrappers, fountain pens, penknives, watches, and clocks; and as the “full-stop” and letter “o” of writing material. German spies also hid invisible ink creatively. Nickolay Hansen, a German spy, agreed to visit a dentist to have a tiny bag with quinine-based secret ink placed under a capped molar. In the mug shot the British took after capturing him, he looks like he has a toothache.

This article is excerpted from Kristie Macrakis’s book “Espionage: A Concise History.”

Kristie Macrakis was Professor of History in the School of History and Sociology at Georgia Tech and the author of many books, including “Seduced by Secrets” (Cambridge University Press), “Prisoners, Lovers, and Spies” (Yale University Press), and “Nothing Is Beyond Our Reach” (Georgetown University Press). She passed away in November 2022.