“Funes the Memorious" and Other Cases of Extraordinary Memory

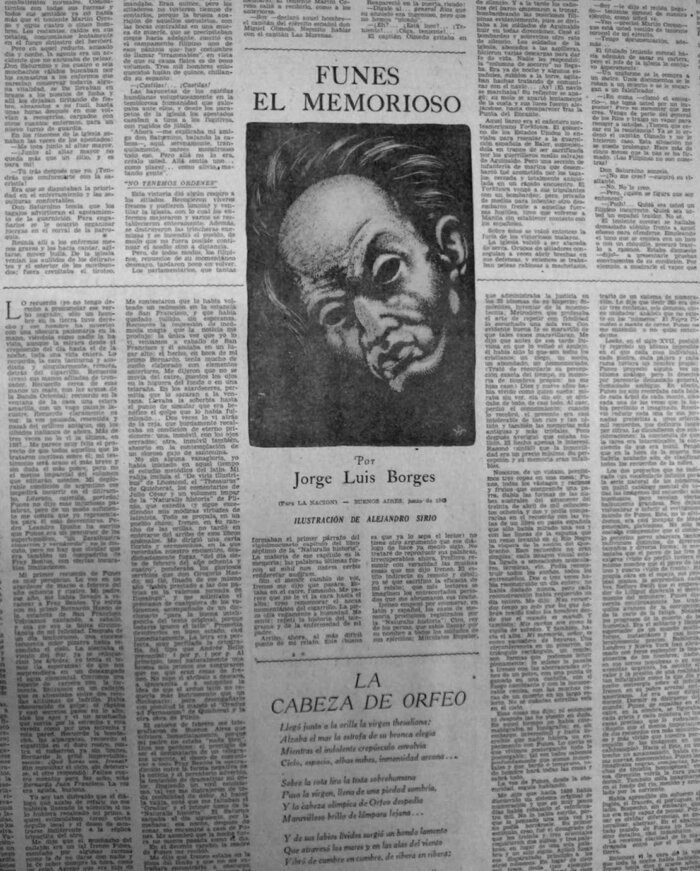

June 7, 1942, was a Sunday like any other amid the altered routine of the Second World War. The front page of the newspaper La Nación reported on the British onslaught, which continued with a bombing campaign over the German industrial area in the Ruhr. On the same page, one could read about the casualties inflicted on the Japanese fleet at Midway and about British infantry tanks’ attacking German positions in the desert. Pages five and six of the paper, in between advertisements for Eno’s “Fruit Salt” (a digestive aid selling at 70 cents per vial) and Fernet Branca (a beverage that should be brought home as one brings a friend), give an account of an earthquake without victims in Mendoza and announce that tire factories can start restoring used tires. In sports, Argentinos Juniors beat Sportivo Alsina by four goals to one in their campaign to reach the premier league, and the entertainment pages promote Pirates of the Caribbean, in Technicolor, and a new movie starring Olivia de Havilland and Henry Fonda at $1.50 a seat.

June 7, 1942, a day like any other according to La Nación, except for a short story appearing in the Arts and Letters section that would turn this issue of the newspaper into a historic document. The first page of this Sunday supplement features a story by Stefan Zweig; the second page contains an essay by Ernesto Sabato praising Galileo; and on the third page, almost hidden in plain sight, for the first time appears “Funes the Memorious,” Jorge Luis Borges’s monumental short story, with an illustration by Alejandro Sirio.

“Funes the Memorious” tells the vicissitudes of Ireneo Funes, a peasant from Fray Bentos, who after falling off a horse and hitting his head hard recovers consciousness with the incredible skill — or perhaps curse — of remembering absolutely everything.

Says Borges of Funes:

Nosotros, de un vistazo, percibimos tres copas en una mesa; Funes, todos los vástagos y racimos y frutos que comprende una parra. Sabía las formas de las nubes australes del amanecer del 30 de abril de 1882 y podía compararlas en el recuerdo con las vetas de un libro en pasta española que sólo había mirado una vez y con las líneas de la espuma que un remo levantó en el Río Negro la víspera de la acción del Quebracho.[We, at a stroke, perceive three cups lying on a table; Funes would see all the shoots and clusters and fruit comprised by a vine. He knew the shapes of the southern clouds at dawn on April 30, 1882, and could compare them in his memory with the streaks on a book of Spanish cover that he had seen only once and with the swirls on the foam raised by an oar in the Río Negro on the eve of the battle of the Quebracho.]

Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) has received universal acclaim for the depth with which he approached matters of philosophic and scientific import in his writings. In Borges’s hands, the topic of infinity comes alive either as a point that contains the universe (“The Aleph”), impregnable labyrinths (“The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths”), a library that is eternally repeated (“The Library of Babel”), stories that subdivide into innumerable possibilities (“The Garden of Forking Paths”), or an imperial map so perfectly detailed that it ends up having the size of the empire itself (“Of Rigor in Science”). In “Funes the Memorious,” a story of barely 12 pages that was eventually published as part of “Ficciones” (1944), Borges again plays with the infinite in a context no less fascinating: the vast labyrinths of memory and the consequences of having an unlimited capacity to remember.

Funes is first mentioned in an obituary of James Joyce, “A Fragment on Joyce,” published in 1941 in the magazine Sur. There, with some measure of sarcasm, Borges says that to read straight through a “monster” like Joyce’s “Ulysses” — a 400,000-word reconstruction of a single day in Dublin — requires another monster able to remember an infinite number of details. The strange thing about the obituary is that Borges barely refers to Joyce or his work and instead describes Ireneo Funes, the main character of the story he was writing at the time.

Entre las obras que no he escrito ni escribiré (pero que de alguna manera me justifican, siquiera misteriosa y rudimental) hay un relato de unas ocho o diez páginas cuyo profuso borrador se titula “Funes el memorioso”. . . . Del compadrito mágico de mi cuento cabe afirmar que es un precursor de los superhombres, un Zaratustra suburbano y parcial; lo indiscutible es que es un monstruo. Lo he recordado porque la consecutiva y recta lectura de las cuatrocientas mil palabras de Ulises exigiría monstruos análogos.

[Among the works that I have not written and will never write (but that somehow justify me, in however mysterious and rudimentary a way) there is a short story, some eight to ten pages long, whose copious draft is entitled “Funes the Memorious.” . . . Of the magical compadrito of my story I can state that he is a precursor to supermen, a suburban, incomplete Zarathustra; what cannot be denied is that he is a monster. I have remembered him because a straight, uninterrupted reading of Ulysses’s four hundred thousand words would require similar monsters.]

In the preface to “Artifices,” the second part of “Ficciones,” Borges argues that “Funes the Memorious” is a long metaphor of insomnia. In fact, toward the end of the story he mentions that Funes found sleeping difficult, because to sleep is to get distracted from the world. Borges gives more details on the way he conceived Funes during his own sleepless nights (perhaps during a sticky summer night at the quinta in Adrogué), in an interview published in the United States:

When I suffered from insomnia I tried to forget myself, to forget my body, the position of my body, the bed, the furniture, the three gardens of the hotel, the eucalyptus tree, the books on the shelf, all the streets of the village, the station, the farmhouses. And since I couldn’t forget, I kept on being conscious and couldn’t fall asleep. Then I said to myself, let us suppose there was a person who couldn’t forget anything he had perceived, and it’s well known that this happened to James Joyce, who in the course of a single day could have brought out “Ulysses,” a day in which thousands of things happened. I thought of someone who couldn’t forget those events and who in the end dies swept away by his infinite memory. In a word that fragmentary hoodlum is me, or is an image I stole for literary purposes but which corresponds to my own insomnia.

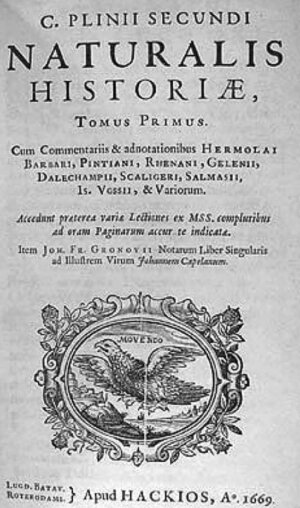

Already in the literature of the first millennium there are references to people with prodigious memory, particularly in the “Naturalis historia” (Natural History) of Pliny the Elder, a sort of encyclopedia that in 37 books describes everything from the geography, science, and technology to the agriculture, medicinal herbs, and insects of ancient Rome. In chapter 24 of book VII, on the topic of memory, Pliny mentions king Cyrus of Persia, who knew the names of all his soldiers; Scipio, who knew the names of all in Rome; Cineas, king Pyrrhus’s ambassador, who learned the names of all the Roman senators just one day after arriving in Rome; Mithridates Eupator, who administered justice in the 22 languages spoken in his empire; Simonides, inventor of mnemonics; or Charmadas the Greek, who could recite by heart any book from a library as though he were reading it.

Pliny considers it a blessing to possess an extraordinary memory. In fact, he starts chapter 24 of book VII saying: “Memoria necessarium maxime vitae bonum cui praecipua fuerit, haut facile dictu est, tam multis eius gloriam adeptis [As to memory, the boon most necessary for life, it is not easy to say who most excelled in it, so many men having gained renown for it].”

Pliny also describes the fragility of memory, arguing that it can be lost, in whole or in part, due to illness, injury, and even panic. As an example he tells the story of a man who lost the capacity to name letters after being struck by a stone, and of another who forgot certain people after falling from a roof. He also mentions Messala Corvinus, the orator, who lost recollection of even his own name.

Borges, it is known, was fascinated by encyclopedias and by the “Naturalis historia” (perhaps the first encyclopedia in history), which in fact he mentions in “Funes the Memorious”: Funes asks the narrator (Borges) for any Latin text, and Borges obliges with volume VII of Pliny’s encyclopedia and Quicherat’s “Thesaurus,” just so the rube will be rudely disappointed upon finding out that one cannot learn such a complicated language using only a book and a dictionary. On their next meeting, however, Funes welcomes Borges by reciting, mockingly, in perfect Latin: “ut nihil non iisdem verbis redderetur auditum” (which, literally translated, means: “Nothing that has been heard can be repeated with the same words”).

Through Funes, Borges, just like Pliny, enters the realm of memory, though his reaction differs from the Roman’s in a crucial regard: while Pliny considers it a virtue to have a prodigious capacity to remember, Borges looks beyond and argues that an extraordinary memory can become a curse. Says Funes, midway through the story:

Más recuerdos tengo yo solo que los que habrán tenido todos los hombres desde que el mundo es mundo. . . . Mi memoria, señor, es como un vaciadero de basura.

[I alone have more memories than all men may have ever had since the world exists. . . . My memory, sir, is like a rubbish heap.]

Given their historical significance, Pliny’s stories are of undeniable value. It is, nonetheless, impossible to judge their veracity, and in fact the characters described in the “Naturalis historia” seem more legendary than real (perhaps arousing Borges’s curiosity even more). To a large extent this is due to the fact that many of Pliny’s descriptions are based on word-of-mouth information, inevitably altered in the telling. For example, when he describes cases of astonishing eyesight in chapter 21 of book VII, Pliny writes that Homer’s “Iliad” was written in such small script that the complete manuscript could fit in a nutshell; he also mentions a man called Strabo, who could recognize objects 135 miles away and who, during the Punic Wars, could sight and even count the enemy ships docked in Carthage from a promontory in Sicily.

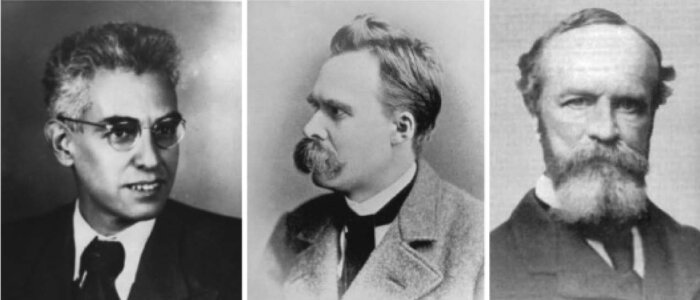

The first properly documented case of extraordinary memory is that of Solomon Shereshevskii, studied by the celebrated Russian psychologist Alexander Luria starting in the 1920s. As Luria reports in his book “The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book about a Vast Memory,” subject S. (as he refers to Shereshevskii to protect his name), unlike everyone else, had to make an effort if he wished to forget something. Shereshevskii possessed a very strong synesthesia — an involuntary link between different senses, like associating numbers with colors — that gave his memories a much richer content and thus made them easier to recollect. These associations, as well as the use of simple mnemonics, allowed Shereshevskii to remember long sequences of numbers and letters many years after first hearing them. After studying Shereshevskii for more than 30 years, Luria confessed his inability to find a limit to S.’s memory, a surprising statement considering that it comes not from an amateur but from one of the foremost psychologists of his time.

There are clear parallels between Shereshevskii and Funes, despite the fact that the former trained his memory based on his synesthesia while for the latter to remember everything was completely natural. It is, however, unlikely that Borges knew of Luria’s work, since Luria published his book (in English) only in 1968, more than 25 years after Borges wrote the story of Funes.

“Funes the Memorious” shows Nietzsche’s influence as well (as Roxana Kreimer describes in an interesting essay); in particular, Borges calls Funes “a precursor to supermen, a suburban, incomplete Zarathustra.” In a brilliant piece on the importance of forgetting, Nietzsche writes:

Imagine the most extreme example, a human being who does not possess the power to forget, who is damned to see becoming everywhere; such a human being would no longer believe in his own being, would no longer believe in himself, would see everything flow apart in turbulent particles, and would lose himself in this stream of becoming; like the true student of Heraclitus, in the end he would hardly even dare to lift a finger. All action requires forgetting, just as the existence of all organic things requires not only light, but darkness as well.

Borges’s fascination with the mind (in this philosophical context I again use “mind” rather than “brain,” though I make no distinction between the two) probably came from his father, a lawyer and psychology professor who introduced him to authors such as William James, considered by many to be the father of modern psychology. In “The Principles of Psychology” (1890), one of his foremost works, James says this about memory:

If we remembered everything, we should on most occasions be as ill off as if we remembered nothing. . . . “The paradoxical result [is] that one condition of remembering is that we should forget. Without totally forgetting a prodigious number of states of consciousness, and momentarily forgetting a large number, we could not remember at all.”

The relation to Funes, Shereshevskii, and Nietzsche is fascinating. Luria, for example, writes that Shereshevskii “was quite inept at logical organization.” Borges, in turn, says that Funes

había aprendido sin esfuerzo el inglés, el francés, el portugués, el latín. Sospecho, sin embargo, que no era muy capaz de pensar.

[had effortlessly learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, however, that he was not very capable of thinking.]

Again: I do not refer to Joyce, Pliny, Luria, Nietzsche, and James so as to question the originality of Borges’s story. On the contrary, these parallel writings provide a philosophical and scientific foundation on which Borges may have found part of his inspiration. Leaving aside the issue of whether Borges knew of Luria’s studies or not — I believe not — I cannot help noticing the uncanny lucidity with which he treats a topic as complex as memory in the context of a short story.

Going back to Funes and other people with extraordinary memory, we must mention Borges himself, who could quote whole passages in Spanish, English, German, and Anglo-Saxon, among other tongues. Though it is possible that blindness may have contributed to his incredible memory (not being distracted by visual stimuli, he could focus, like Democritus before him, on his thoughts and the stream of his remembrance), Borges’s youthful realization that he, like his father, would lose his eyesight took him on a monumental quest for knowledge while he could still see. María Kodama [his widow] remembers that, on one of her first encounters with Borges, he asked her to find an excerpt from a book. The fragment, the writer said, was on an odd-numbered page near the middle of the book. Kodama started to read a page at random and Borges, amazingly, guided her to the right page even though he had been blind for many years and — as he jotted on the first page — had read the book in 1916, decades before this encounter with Kodama.

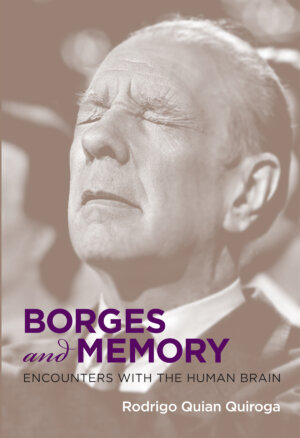

Rodrigo Quian Quiroga is Director of the Centre for Systems Neuroscience at the University of Leicester. He is the author of “Borges and Memory,” “Principles of Neural Coding,” “Imaging Brain Function with EEG,” and “The Forgetting Machine.”