The Mega-Wars That Shaped World History

While trying to assess the probabilities of recurrent natural catastrophes and catastrophic illnesses, we must remember that the historical record is unequivocal: these events, even when combined, did not claim as many lives and have not changed the course of world history as much as the deliberate fatal discontinuities that historian Richard Rhodes calls man-made death, the single largest cause of non-natural mortality in the 20th century. Violent collective death has been such an omnipresent part of the human condition that its recurrence in various forms conflicts lasting days to decades, homicides to democides, is guaranteed. Long lists of the past violent events can be inspected in print or in electronic databases.1

Even a cursory examination of this record shows yet another tragic aspect of that terrible toll: so many violent deaths had no or only a marginal effect on the course of world history. Others, however, contributed to outcomes that truly changed the world. Large death tolls of the 20th century that fit the first category include the Belgian genocide in the Congo (began before 1900), Turkish massacres of Armenians (mainly in 1915), Hutu killings of Tutsis (1994), wars involving Ethiopia (Ogaden, Eritrea, 1962-1992), Nigeria and Biafra (1967-1970), India and Pakistan (1971), and civil wars and genocides in Angola (1974-2002), Congo (since 1998), Mozambique (1975-1993), Sudan (since 1956 and ongoing), and Cambodia (1975-1978). Even in our greatly interconnected world, such conflicts can cause more than one million deaths (as did all of the just listed events) and go on for decades without having any noticeable effect on the cares and concerns of the remaining 98 to 99.9 percent of humanity.

By contrast, the modern era has seen two world wars and interstate conflicts that resulted in long-lasting redistribution of power on global scales, and intrastate (civil) wars that led to the collapse or emergence of powerful states. I call these conflicts transformational wars and focus on them next.

Violent collective death has been such an omnipresent part of the human condition that its recurrence in various forms conflicts lasting days to decades, homicides to democides, is guaranteed.

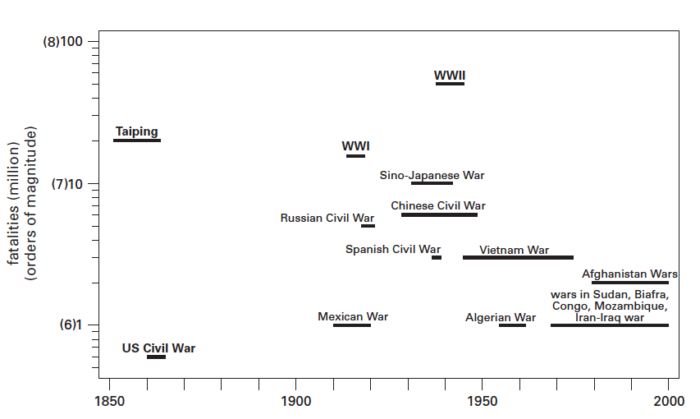

There is no canonical list of transformational wars of the 19th and 20th centuries. Historians agree on the major conflicts that belong in this category but differ as to others. My own list is fairly restrictive; a more liberal definition of worldwide impacts could extend the list. A long-lasting transformational effect on the course of world history is a key criterion. And most of the conflicts I have called transformational share another characteristic: they are mega-wars, claiming the lives of more than million combatants and civilians. By mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson’s definition, based on the decadic logarithm of total fatalities, most would be magnitude 6 or 7 wars (figure 1). Their enumeration starts with the Napoleonic wars, which began in 1796 with the conquest of Italy and ended in 1815 in a refashioned, and for the next 100 years also remarkably stable, Europe. This stability was not basically altered, either by brief conflicts between Prussia and Austria (1866) and Prussia and France (1870-1871) or by repeated acts of terror that killed some of the continent’s leading public figures while others, including Kaiser Wilhelm I and Chancellor Bismarck, escaped assassination attempts.

The next entry on my list of transformational wars is the protracted Taiping war (1851-1864), a massive millennial uprising led by Hong Xiuquan.2 This may seem like a puzzling addition to readers not familiar with China’s modern history, but the Taiping uprising, aimed at achieving an egalitarian, reformist kingdom of heaven on earth, exemplifies a grand transformational conflict because it fatally undermined the ruling Qing dynasty, enmeshed foreign actors in China’s politics for the next 100 years, and brought in less than two generations the end of the old imperial order. With about 20 million fatalities, its human costs were higher than the aggregate losses of combatants and civilians in World War I.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) should be included because it opened the way toward the country’s rapid ascent to global economic primacy.3 GDP surpassed that of Great Britain by 1870; by the 1880s the United States became the technical leader and the world’s most innovative economy, firmly set on its rise toward superpower status.

World War I (1914-1918) traumatized all European powers, utterly destroyed the post-Napoleonic pattern, ushered in Communism in Russia, and brought the United States into global politics for the first time. And — a fact often forgotten — it also began the destabilization of the Middle East by dismembering the Ottoman Empire and creating the British and French Mandates whose dissolution led eventually to the formation of the states of Jordan (1923), Saudi Arabia and Iraq (1932), Lebanon (1941), Syria (1946), and Israel (1948).4

World War II (1939-1945) is, of course, the quintessential transformational war, not only because of the sweeping changes it brought to the global order but also because of the decades-long shadows it cast over the rest of the 20th century. Virtually all the key post-1945 conflicts involving that war’s protagonists — the USSR, the United States, and China in Korea; France and the United States in Vietnam; the USSR in Afghanistan; superpower proxy wars in Africa — can be seen as actions designed to maintain or challenge the outcome of WWII. Arguably, other conflicts might seem to qualify, but closer examination shows that they did not fundamentally alter the past but rather reinforced the changes set in motion by transformational wars. Two cases are the undeclared but no less fatal wars waged by a variety of means from outright mass killings to deliberate famines against the people of the USSR by Stalin between 1929 and 1953, and against the Chinese people by Mao between 1949 and 1976. The actual toll of these brutalities will be never known with any accuracy, but even the most conservative estimates put the combined death toll at above 70 million.

Objections can be made to the durations of the listed transformational wars. For example, 1912, the beginning of the Balkan wars, and 1921, the conclusion of the civil war that established the Soviet Union, may be more appropriate dating of World War I. And one could say that World War II started with Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1933 and ended only with the Communist victory in China in 1949.

Even a rather restrictively defined list of transformational wars adds up to 42 years of conflicts in two centuries, with conservatively estimated total casualties (combatant and civilian) of about 95 million (averaging 17 million deaths per conflict).

Even a rather restrictively defined list of transformational wars adds up to 42 years of conflicts in two centuries, with conservatively estimated total casualties (combatant and civilian) of about 95 million (averaging 17 million deaths per conflict). The mean recurrence rate is about 35 years, and an implied probability of a new conflict of that category stands at roughly 20 percent during the next 50 years. All these numbers could be reduced by including the wars of the 18th century, a time of remarkably lower intensity of all violent conflicts than the two preceding and two subsequent centuries.5 On the other hand, most of that century belonged distinctly to the preindustrial era, and most of the then major powers (e.g., Qing China, enfeebled Mughal India, and weakening Spain) were nearing the end of their influence. Thus the exclusion of 18th-century wars makes sense.

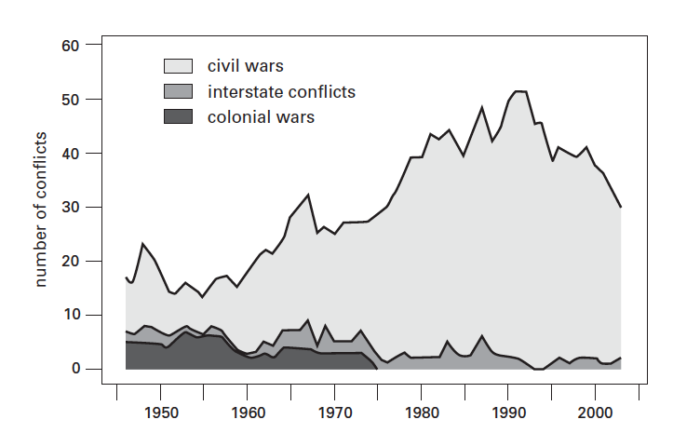

Three important conclusions emerge from the examination of all armed conflicts of the past two centuries. First, until the 1980s there was an upward trend in the total number of conflicts starting in each decade; second, there was an increasing share of wars of short duration (less than one year).6 Implications of these findings for future transformational conflicts are unclear. So is the fact that between 1992 and 2003 the worldwide number of armed conflicts declined by 40 percent, and the number of wars with 1,000 or more battle deaths dropped by 80 percent (Figure 2).7 These trends were clearly tied to declining arms trade and military spending during the post-Cold War era; it is thus unclear if the decade was a welcome singularity of reduced violence or a brief aberration.

The most important finding regarding the future likelihood of violent conflicts comes from Lewis Fry Richardson’s search for causative factors of war and his conclusion that wars are largely random catastrophes whose specific time and location we cannot predict but whose recurrence we must expect. That would mean that wars are like earthquakes or hurricanes, leading scientist Brian Hayes to speak of warring nations that “bang against one another with no more plan or principle than molecules in an overheated gas.” At the beginning of the 21st century it could be argued that new realities have greatly diminished the recurrence of many possible conflicts, thus, to continue the metaphor, greatly reducing the density and the pressure of the gas.

The European Union is widely seen as a near-absolute barrier to armed conflicts involving its members. America and Russia may not be strategic partners, but they surely do not take the same adversarial positions that they held for two generations preceding the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The Soviet Union and China came very close to a massive conflict in 1969 (a close call that prompted Mao’s rapprochement with the United States), but today China buys the top Russian weapons and would gladly buy all the oil and gas that Siberia could offer. And Japan’s very constitution prevents it from attacking any country. This reasoning would negate, or at least severely undercut, Richardson’s argument, but it would be a mistake to use it when thinking about long spans of history. Neither short-term complacency nor understandable reluctance to imagine the locale or cause of the next transformational was a good argument against its rather high probability.

In 1790 no Prussian high officer or Czarist general could suspect that Napoleon Bonaparte, a diminutive Corsican from Ajaccio, who became known to his troops as le petit caporal, would set out to redraw the map of Germany before embarking on a mad foray into the heart of Muscovy.8 In 1840 the Emperor Daoguang could not have dreamt that the dynastic rule that had lasted for millennia would come close to its end because of Hong Xiuquan, a failed candidate of the state Confucian examination who came to think of himself as a new Christ and who led the protracted Taiping rebellion. And in 1918 the victorious powers, dictating a new European peace at Versailles, would not have credited that Adolf Hitler, a destitute, neurotic would-be artist and gassed veteran of the trench warfare, would within two decades undo their new order and plunge the world into its greatest war.

In 1918 the victorious powers, dictating a new European peace at Versailles, would not have credited that Adolf Hitler, a destitute, neurotic would-be artist and gassed veteran of the trench warfare, would within two decades undo their new order and plunge the world into its greatest war.

New realities may have lowered the overall probability of globally transformational conflicts, but they have not surely eliminated their recurrence. Causes of new conflicts could be found in old disputes or in surprising new developments. During 2005-2007 the probabilities of several new conflicts rose from vanishingly low to decidedly non-negligible as the North Korean threat led Japan to raise the possibility of an attack across the Sea of Japan; as the chances of a U.S.-Iran war (nonexistent during the Pahlavi dynasty, very low even after the Revolutionary Guards took the U.S. embassy hostages) were widely discussed in public; and as China and Taiwan continued their high-risk posturing regarding the fate of the island.

Richardson’s reasoning and the record of the past two centuries imply that during the next 50 years the likelihood of another armed conflict with potential to change world history is no less than about 15 percent and most likely around 20 percent. As in all cases of such probabilistic assessments, the focus is not on a particular figure but rather on the proper order of magnitude. No matter whether the probability of a new transformational war is 10 percent or 40 percent, it is 1-2 OM higher than that of the globally destructive natural catastrophes that were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Before leaving this topic I must note the risks of an accidentally started, transformational mega-war. As noted, we have lived with this frightening risk since the early 1950s and during the height of the Cold War. Casualties of an all-out thermonuclear exchange between the two superpowers (including its lengthy aftermath) were estimated to reach hundreds of millions. 9 Even a single isolated miscalculation could have been deadly. Lachlan Forrow and others wrote in 1998 that an intermediate-sized launch of warheads from a single Russian submarine would have killed nearly instantly about 6.8 million people in eight U.S. cities and exposed millions more to potentially lethal radiation.

The probabilities of such mishaps escalating out of control rose considerably during periods of heightened crisis, when a false alarm was much more likely to be interpreted as the beginning of a thermonuclear attack.

On several occasions we came perilously close to such a fatal error, perhaps even to a civilization-terminating event. Nearly four decades of the superpower nuclear standoff were punctuated by a significant number of accidents involving nuclear submarines and long-range bombers carrying nuclear weapons, and by hundreds of false alarms caused by malfunctions of communication links, errors of computerized control systems, and misinterpretations of remotely sensed evidence. Many of these incidents were detailed in the West after a lapse of time, and there is no doubt that the Soviets could have reported a similar (most likely, larger) number.10

The probabilities of such mishaps escalating out of control rose considerably during periods of heightened crisis, when a false alarm was much more likely to be interpreted as the beginning of a thermonuclear attack. A series of such incidents took place during the most dangerous moment of the entire Cold War, the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Fortunately, there was never any accidental launch, either attributable to hardware failure (crashing nuclear bomber, grounded nuclear submarine, temporary loss of communication) or to misinterpreted evidence. One of the architects of the Cold War regime in the United States concluded that the risk was small because of the prudence and unchallenged control of the leaders of the two countries.11

The size of the risk depends entirely on the assumptions made in order to calculate cumulative probabilities of avoiding a series of catastrophic mishaps. Even if the probability of an accidental launch were just 1 percent in each of some 20 known U.S. incidents (the chance of avoiding a catastrophe being 99 percent), the cumulative likelihood of avoiding an accidental nuclear war would be about 82 percent, or, as the scholar Alan Phillips rightly concluded, “about the same as the chance of surviving a single pull of the trigger at Russian roulette played with a six-shooter.” This is at once correct reasoning and a meaningless calculation. As long as the time available to verify the real nature of an incident is shorter than the minimum time needed for a retaliatory strike, the latter course can be avoided and the incident cannot be assigned any definite avoidance probability. If the evidence is initially interpreted as an attack under way, but a few minutes later this is entirely discounted, then in the minds of decision-makers the probability of avoiding a thermonuclear war goes from 0 percent to 100 percent within a brief span of time. Such situations are akin to fatal car crashes avoided when a few centimeters of clearance between the vehicles makes the difference between death and survival. Such events happen worldwide thousands of times every hour, but an individual has only one or two such experiences in a lifetime, so it is impossible to calculate the probabilities of any future clean escape.

With more countries possessing nuclear weapons, it is reasonable to argue that chances of accidental launching and near-certain retaliation have been increasing steadily since the beginning of the nuclear era.

The demise of the USSR had an equivocal effect. On the one hand it undoubtedly diminished the chances of accidental nuclear war thanks to a drastic reduction in the number of warheads deployed by Russia and the United States. In January 2006, Russia had approximately 16,000 warheads compared to the peak USSR total of nearly 45,000 in 1986, and the United States had just over 10,000 warheads compared to its peak of 32,000 in 1966.12 Totals of strategic offensive warheads fell rapidly after 1990 to less than half of their peak counts, and the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, signed in May 2002, envisaged further substantial cuts. On the other hand, it is easy to argue that because of the aging of Russian weapons systems, a decline in funding, a weakening of the command structure, and the poor combat readiness of the Russian forces, the risk of an accidental nuclear attack has actually increased.

Moreover, with more countries possessing nuclear weapons, it is reasonable to argue that chances of accidental launching and near-certain retaliation have been increasing steadily since the beginning of the nuclear era. Since 1945 an additional nation has acquired nuclear weapons roughly every five years; North Korea and Iran have been the latest candidates.

This article is excerpted from “Global Catastrophes and Trends: The Next Fifty Years.”

Vaclav Smil is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Manitoba. He is the author of over forty books, most recently “Growth.” In 2010 he was named by Foreign Policy as one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers. In 2013 Bill Gates wrote on his website that “there is no author whose books I look forward to more than Vaclav Smil.”

References:

- Richardson, L. F. 1960. Statistics of Deadly Quarrels. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Boxwood Press.; Singer, J. D., and M. Small. 1972. The Wages of War, 1816–1965: A Statistical Handbook. New York: Wiley; Wilkinson, D. 1980. Deadly Quarrels. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Spence, J. D. 1996. God’s Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Jones, H. M. 1971. The Age of Energy: Varieties of American Experience, 1865–1915. New York: Viking U.S.

- Fromkin, D. 2001. A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: Henry Holt.

- Brecke, P. 1999. Violent conflicts A.D. 1400 to the present in different regions of the world. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Peace Science Society, Ann Arbor.

- Kaye, G. D., D. A. Grant, and E. J. Emond. 1985. Major Armed Conflict: A Compendium of Interstate and Intrastate Conflict, 1720 to 1985. Ottawa: Department of National Defense.

- Human Security Centre. 2006. Human Security Report 2005: War and Peace in the 21st Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zamoyski, A. 2004. Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March. New York: HarperCollins.

- Coale, A. 1985. On the demographic impact of nuclear war. Population and Development Review 9: 562–568.

- Sagan, S. D. 1993. The Limits of Safety. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.; Britten, S. 1983. The Invisible Event. London: Menard Press.; Calder, N. 1980. Nuclear Nightmares. New York: Viking.

- Bundy, M. 1988. Danger and Survival: Choices about the Bomb in the First Fifty Years. New York: Random House.

- Norris, R. S., and H. M. Kristensen. 2006. Global nuclear stockpiles, 1945–2006. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 62 (4): 64–66.