The Uncanny Keyboard

“We learn with mingled emotions — transcending dismay and yet appreciably milder than despair — that Dr. Lin Yutang, our favorite oriental author … has invented a Chinese typewriter.” So began a 1945 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune that revealed to an American reading public the quixotic new pursuit of a celebrated cultural commentator, and beloved author of the bestselling titles “My Country and My People” and “The Importance of Living.” So allergic were they to this startling news, the authors explained, that at first they simply did not believe it. The news would have been “incredible,” they stressed, if it had not come directly from Lin’s publisher. “Seeking additional enlightenment,” the reporters continued, “we consulted our laundryman, Ho Sin Liu.”

“Tell us, Ho, about how big would a Chinese typewriter need to be to cover the whole range of your delightful tongue?”

“Ho, ho!” Ho replied, wittily punning his name into an English exclamation point. … How indeed shall I answer such an interrogation unless with another? Have you seen the Boulder dam?”

Lin Yutang was born in 1895 in Fujian province, the same year that Taiwan was lost to Japan following the humiliation of the first Sino-Japanese War. Raised in a Christian household, Lin entered St. John’s University in Shanghai in 1911, the year a republican revolution delivered the death blow to an already weakened Qing dynasty. His educational career was marked by distinction, continuing at Tsinghua University from 1916 to 1919, and then Harvard in 1919 and 1920. By 40 years of age, Lin was a celebrated author in the United States and beyond, becoming one of the most influential cultural commentators on China of his generation.

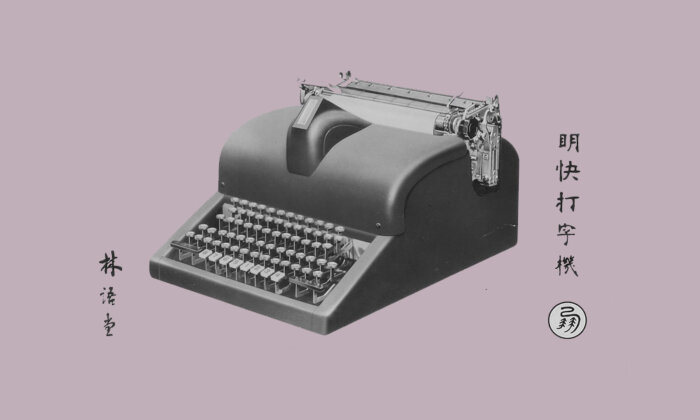

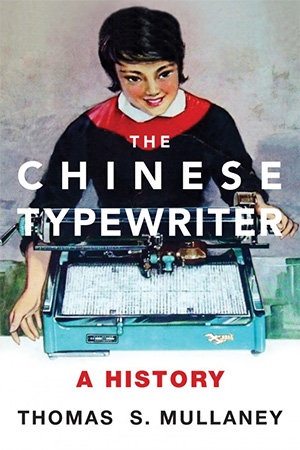

Years before his breakout English-language debut, Lin Yutang began to contemplate a question that exerted a magnetic pull on the minds of many: the question of how to develop a typewriter for the Chinese language that could achieve the scope and reputation of its Western counterpart. With these inspirations, Lin set off down a path that many years later would lead to perhaps the most well-known, but also most poorly understood, Chinese typewriter in history: the “MingKwai” or “Clear and Fast” Chinese typewriter, announced to the world starting in the mid-1940s.

When MingKwai made its first appearance, the writer at the Chicago Daily Tribune and his “laundryman” would be proven wrong: MingKwai was considerably smaller than the Boulder Dam. In fact, it looked uncannily like a “real typewriter.” Measuring 14 inches wide, 18 inches deep, and nine inches high, the machine was only slightly larger than common Western typewriter models of the day. More notably, MingKwai was the first Chinese typewriter to possess the sine qua non of typewriting, a keyboard. Finally, it would seem, the Chinese language had joined the rest of the world by creating a typewriter just like ours.

MingKwai may have looked like a conventional typewriter, yet its behavior would have quickly confounded anyone who sat down to try it out.

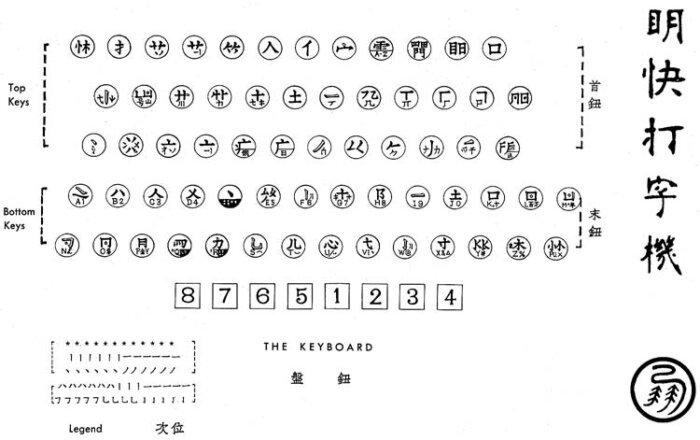

MingKwai may have looked like a conventional typewriter, yet its behavior would have quickly confounded anyone who sat down to try it out. Upon depressing one of the machine’s 72 keys, the machine’s internal gears would move, and yet nothing would appear on the paper’s surface — not right away, at least. Depressing a second key, the gears would move again, yet still without any output on the page. With this second keystroke, however, something curious would happen: Eight Chinese characters would appear, not on the printed paper, but in a special viewfinder built into the machine’s chassis. Only with the depression of a third key — specifically one of the machine’s eight number keys — would a Chinese graph finally be imprinted on the page.

Three keystrokes, one impression. What in the world was going on?

What is more, the Chinese graph that appeared on the page would bear no direct, one-to-one relationship with any of the symbols on the keys depressed during the three-part sequence. What kind of typewriter was this, that looked so uncannily like the real thing, and yet behaved so strangely?

If the fundamental and unspoken assumption of Western-style typewriting was the assumption of correspondence — that the depression of a key would result in the impression of the corresponding symbol upon the typewritten page — MingKwai was something altogether different. Uncanny in its resemblance to a standard Remington- or Olivetti-style device, MingKwai was not a typewriter in this conventional sense, but a device designed primarily for the retrieval of Chinese characters. The inscription of these characters, while of course necessary, was nonetheless secondary. The depression of keys did not result in the inscription of corresponding symbols, according to the classic what-you-type-is-what-you-get convention, but instead served as steps in the process of finding one’s desired Chinese characters from within the machine’s mechanical hard drive, and then inscribing them on the page.

The machine worked as follows. Seated before the device, an operator would see 72 keys divided into three banks: upper keys, lower keys, and eight number keys. First, the depression of one of the 36 upper keys triggered movement and rotation of the machine’s internal gears and type complex — a mechanical array of Chinese character graphs contained inside the machine’s chassis, out of view of the typist. The depression of a second key — one of the 28 lower keys — initiated a second round of shifts and repositionings within the machine, now bringing a cluster of eight Chinese characters into view within a small window on the machine — a viewfinder Lin Yutang called his “Magic Eye.” Depending upon which of these characters one wanted — one through eight — the operator then depressed one of the number keys to complete the selection process and imprint the desired character on the page.

In creating the MingKwai typewriter, then, Lin Yutang had not only invented a machine that departed from the likes of Remington and Underwood, but so too from the approaches to Chinese typewriting put forth by the many designers before him. Lin invented a machine, indeed, that altered the very act of mechanical inscription itself by transforming inscription into a process of searching. The MingKwai Chinese typewriter combined “search” and “writing” for arguably the first time in history, anticipating a human-computer interaction now referred to as input, or shuru in Chinese.

Thomas S. Mullaney is Professor of History at Stanford University and the author of “The Chinese Typewriter,” from which this article is excerpted.