A City Cast in Concrete, Trapped Under Unbearable Heat

Sri Lanka is an island, 7.8731°N, 80.7718°E — that is to say, just below India, just above the equator. There are mountains, rainforests, beaches, ancient ruins, and — before we turn into a travel brochure — enough problems to last several lifetimes.

One of these problems is Colombo.

On the surface, Colombo is a good pitch. It’s a small city, roughly 38 square kilometers. It comes with a beach and a port. It has the most wealth and best infrastructure in the country. The weather is warm all year round, the food ranges between dirt cheap and pretentiously overpriced, and . . . you’re now picturing a sort of semi-idyllic tropical paradise where business deals are struck in a verandah overlooking the sea.

To those more familiar with it, Colombo is a baking patch of asphalt and concrete, staring out with drying eyes at an indifferent sea. It’s a tropical paradise to those who can afford to live in hotels, but for the majority of its residents, it is exhausting. To walk or cycle anywhere in Colombo, even up the lane, is to slowly succumb to a wet, sickly heat, to arrive dripping in your own sweat.

There is a peculiar humiliation in this heat. The cold you can button up against; this heat makes savages of us all.

Perhaps for this reason, walking anywhere is an activity reserved mostly for the poor. Those who can afford it shelter in private transport; those who can really afford it spend half their lives moving from one air-conditioned environment to another.

I learned this firsthand in 2020, when I moved from a fairly green suburb to the heart of Mount Lavinia, a dense seaside suburb into which Colombo spills. My logic was simple: I’d spent years locked away in my own rooms, staring at a computer screen, writing furiously. I needed to get out more, and the city beckoned. The beach was within walking distance, I had friends around, and Mount Lavinia’s lively streets offered much more than the small store to which I made my daily pilgrimage for cigarettes.

What happened was that I became even more shut-in. It was too damn hot to walk outside in the day; the beach, so close to my door, became a distant memory. Crossing the road felt like being a cut-rate vampire, cursing a sun that beat down on me like a crucifix.

To my surprise, nights were no different. Venturing out, even at midnight, felt like being hit by a wall of damp, rolling heat — this time from below and around me. As the year heated up, my bedroom began to feel like an oven.

I initially discounted this as an isolated phenomenon; maybe it was just my neighborhood. After all, the road I live on is a smattering of flats (built as cheaply as possible) and an upwardly mobile waththa (a Sri Lankanism for a mishmash of tiny dwellings, just a few steps above a slum). I live in a haphazard maze of sorts, the kind where cooling breezes go to die.

And yet, as I made my way around the city in all kinds of weather — riots and protests included — I began to recognize that Colombo was suspiciously hot. Too hot for a beach town.

There is a peculiar humiliation in this heat. The cold you can button up against; this heat makes savages of us all.

But here’s where things get odd. People I’ve spoken to over the past few months — particularly those in their 60s and 70s — recall a Colombo where they comfortably went for long walks and bicycle rides, a green city where the noise and bustle of the harbor gave way to cool glades and green paths. Over a much shorter time span, I had been coming to Colombo daily at least since 2010 — first for school, then for work — and once-walkable areas of the city had become scorching, difficult places to traverse.

But you know what they say: Anecdotal evidence is only evidence of an anecdote. Were these recollections true, or was it simply the rose-tinted lenses of nostalgia? And why do other coastal cities of Sri Lanka seem so much more comfortable than Colombo?

When I spoke about this to Nisal Periyapperuma, my good friend and cofounder of Watchdog (the open-source research collective that we run), he hit upon a simple but effective test. Nisal purchased a bunch of infrared thermometers, and, with our colleagues Sathyajit Loganathan and Ishan Marikar, we walked across a widely used section of the city in September 2022, between 2 and 3 p.m. As we walked, we logged the surface temperature, conditions (whether it was sunny or shaded), and the GPS coordinates.

This (admittedly low-budget and unsystematic) test gave us 158 observations. Figure 1 shows how they look when mapped, after a little bit of averaging.

The zone with the highest surface temperature, on average, read at 54°C,

or 129°F.

This might be odd to wrap your head around. Think of it as a composite indicator of temperature and humidity; it’s a better measure of heat as we feel it. For example, a bone-dry 32°C (90°F) is tolerable — something I’ve experienced firsthand; you sweat, and the sweat cools you off until you can get to shelter. But a muggy, humid 32°C is difficult to breathe in, and no matter how much you sweat, all you can do is slowly overheat.

Figure 1: Digital image of an overhead map of roads in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Image by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne.

Simultaneously, I began investigating the air. In his much-discussed 2020 novel “The Ministry for the Future,” Kim Stanley Robinson popularized the idea of the wet-bulb temperature. The concept originated when the US military sought to understand outbreaks of heat-related illnesses and eventually made its way into climate science. In a nutshell, wet-bulb temperature is the lowest temperature to which air can be cooled by the evaporation of water.

Let’s put this in perspective. The 2010 Russian heat waves, which killed some 56,000 people, saw wet-bulb temperatures of 28°C (82°F). The 2022 heat waves in the United Kingdom reached wet-bulb temperatures of 25°C (77°F). In Colombo, this is just another Tuesday. Our wet-bulb temperature stays steady at 26–27°C throughout most of the year.

Baking hot streets, heat waves in the air. It wasn’t just me and some anecdotes: We have an actual problem. How did this happen, and why?

This is where we must examine two converging phenomena. First, Colombo has been urbanizing rapidly over the past several decades. Sri Lanka came relatively late to the urbanization game — it used to be called “one of the least urbanized countries” on the planet — but once we got there, we set off for the races. UN-Habitat data suggests that between 1995 and 2017, Colombo’s urban area grew by 9.57 percent per year — a pretty high figure, even by global standards.

To my parents’ generation, there were only a handful of landmarks on the horizon: a smattering of towers, a single giant market (Pettah) where you could buy anything or get scammed out of every last cent at a few well-known shops. It was otherwise row upon row of homes. Fast-forward to today: I’m sitting in a cheap apartment, staring at miles of cheap apartments, office blocks, and the occasional glimpse of the oft-mocked Lotus Tower — a landscape my mother disdainfully calls the “concrete jungle.”

With this comes the second phenomenon. There’s a well-observed correlation between urbanization and higher surface temperatures. As people build — more roads, more apartments — they remove greenery to make space and replace leaves and earth with surfaces like asphalt and concrete, which trap and retain heat.

In a collaboration between Rajarata University of Sri Lanka and the University of Tsukuba in Japan, researchers used LANDSAT data to examine surface temperatures in Colombo at different moments during the decades-long process of rapid urbanization. Using temperature measurements from 1997, 2007, and 2017, the study tells the story of a cooler city by the sea, and how it went from a pleasant 25–27°C (77-80.6°F) to a staggering 31°C (87.8°F), or more. The heat maps created by the authors for 1997 are dominated by calming hues of green, but by 2017, a sprawling fungus of red heat spreads its tendrils in every direction. The old-timers weren’t just being nostalgic; in their time, it would indeed have been much, much cooler.

What happens when we have such an endless, uninterrupted mass of concrete and asphalt?

As urbanization spread, so did the loss of green spaces — especially trees. As the surface-temperature study’s authors point out, this happened across the central business district, near the harbor, across the coastal belt, and along the road networks. Greenery, which cools areas by providing shade and heat loss through evaporation, began to vanish, replaced by mounds of concrete, steel, and asphalt. These surfaces store heat during the day and release it at night, leading to the conditions I’ve been describing: unrelenting heat from above during the day and below after dark.

I wanted to understand just how much this effect might have intensified since the study’s measurements, because, frankly, 2017 feels like a distant memory. While I couldn’t replicate the entire study, I had a trick up my sleeve: Google and the World Resources Institute have a project called Dynamic World that provides detailed satellite imagery maps of land cover. Using deep learning, Dynamic World tries to figure out whether a given pixel is water, trees, grass, cropland, and so on. And unlike the LANDSAT imagery used in the paper, Dynamic World uses Sentinel-2, a newer satellite with better sensors.

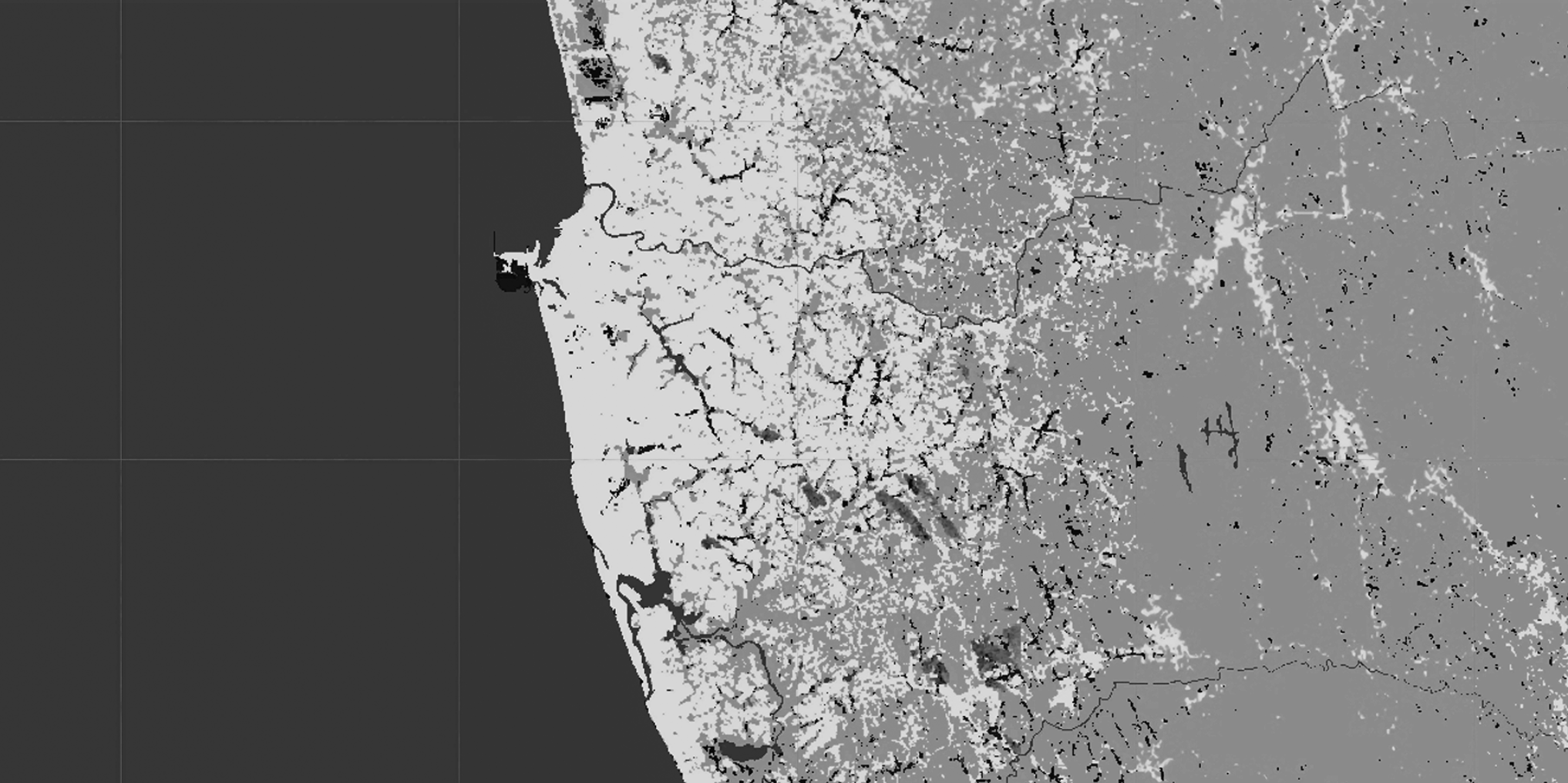

The results are disheartening. The darkest area on the left of the image is water. On land, the white areas are built up: a rising tide of artificial materials baking in the sun. The medium-gray regions inland are dominated by greenery and are as yet undeveloped. Figure 2 looks broadly at the same area that the LANDSAT maps did.

Figure 3 is a closer view, which shows just how much of the city has become a contiguous mass of artificial surfaces, unshaded and lacking green spaces. What happens when we have such an endless, uninterrupted mass of concrete and asphalt? This is where urbanization and temperature converge to create the urban heat island effect.

Figure 2: Satellite map of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Image by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, created using Dynamic World.

This dataset is produced for the Dynamic World Project by Google in partnership with the National Geographic Society and the World Resources Institute.

Figure 3: Satellite map of Colombo, Sri Lanka (detailed view of Figure 2). Image by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne,

created using Dynamic World. This dataset is produced for the Dynamic World Project by Google in

partnership with the National Geographic Society and the World Resources Institute.

The urban heat island effect was first described in 1818, although not by that name. Based on detailed temperature measurements collected in London, British chemist and meteorologist Luke Howard noted that urban areas tend to have higher temperatures than surrounding rural expanses. By the outbreak of World War II, researchers attempting to understand local climates were documenting the phenomenon all over the world and trying to figure out its effects. In general, they found that daytime temperatures between urban and rural areas tended to have differences between three and five degrees Celsius. At night, the differences were more intense: Urban areas cooled much more slowly. The difference between an urban area at night and a rural area could be as much as 12°C.

This doesn’t sound like much, and it isn’t if you’re in a cold country. An increase from 10 to 15°C might actually seem like a welcome change. However, if you’re living on a tropical island, especially one that’s quite humid, a five-degree increase is the difference between a comfortable day and heat-wave conditions. This is where that nasty foe, the wet-bulb temperature, kicks in. Past a certain point, body heat is no longer being effectively carried away by sweat.

The dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief.

How do the denizens of Colombo counter this? Why, air conditioning, if you can afford it, and opting for private transport. These are two of the great boons of Sri Lankan city life. But each dumps more heat into the environment.

The effect never stops in the hot months. Buildings heat up, they stay hot at night, and heat up again during the day. Houses with concrete-slab roofs, in tropical conditions, become miniature ovens.

And this is how you get to me, sitting out here on a cramped balcony at midnight because it’s too hot to sleep inside. Stick some soil in my apartment and call it a greenhouse. Now add the other negative effects of the urban heat island effect: elevated ground-level ozone, increased mortality, increased energy consumption, more greenhouse gases, increased hospitalization of children and the elderly, and less biodiversity, because of the death of urban plants and birds.

The dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief.

So, how do we get out of this mess? This is the moment where I ought to reach into my science-fictional imagination and pull out the grand ideas. Artificial clouds, or rockets heading for the sky, spreading reflective particles to block out the sun.

Before we blast into the stratosphere, let’s look at the approaches that exist today.

The first approach is the realm of ambitious makeovers. The push for greener cities has increased dramatically over the last decade. Serious funding and thought are being spent by big international movers and shakers — including the Asian Development Bank, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UN-Habitat, and the EU Commission — and this is to say nothing of the millions of smaller pushes that happen before something gets this big.

This kind of globalist, top-down push lends itself to elaborate visions of the future, ones in which the nation-state plays a central role. Take, for instance, China’s Liuzhou Forest City, designed by Stefano Boeri Architetti, which will supposedly contain a million plants built into almost every visible surface. The idea is that this will keep the temperatures down and the air much cleaner than in a typical city.

It’s not a bad idea, at least as far as the climate math is concerned. However, I’m skeptical of these grand ambitions. Grand plans never survive contact with reality, even in totalitarian regimes. The UK’s garden cities movement has seen its fair share of failures, and the same goes for high-tech “smart” cities. Large, centrally planned projects like these tend to encounter two problems.

One, they’re expensive and difficult to implement. Reorganizing Colombo to reduce the urban heat island effect would be a nigh-impossible challenge, involving billions of dollars and a nightmare of legislature and bureaucracy.

A complex system, once set in motion, is hard to change. Its inertia is greater than the sum of all moving parts. And a city is a complex system.

Two, they often ignore and brutally reshape local communities. We can turn to Jane Jacobs’s work in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” or to more recent documentation from Colombo, where poorer communities have been evicted and forced into government housing against their will. The incentives of large, top-down change are written by those who have power over such systems; as Jacobs argues, these empowered elites and their metrics for success tend to oversimplify and overlook the lives, cultures, and habitual patterns of people who actually live in the places being changed.

Colombo, in particular, has been on the receiving end of many ambitious and all-encompassing Plans. I capitalize the word here because these Plans are giant political projects, imbued with the character and values of those championing them, and because they never seem to evolve from Plans to Action; they’re too big-picture to become reality; they exist in an abstract well of good intentions and power plays.

There’s the Colombo Megacity project, an ever-mutating hydra often championed by Ranil Wickramasinghe, the president of Sri Lanka from 2022 to 2024, who also served as prime minister several times since the 1990s. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, the former president, had his “Vistas of Splendor and Prosperity,” apparently inspired by his former stint running the Defense and Urban Planning portfolios and getting armed soldiers to chase young couples out of parks.

Then there’s the Urban Development Authority’s rather optimistic Development Plans. Unfortunately, given how tightly coupled the bureaucracy is with family political control and personal visions of grandeur, what actually emerges is “white elephant” projects: wasteful delusions of grandeur maintained at significant taxpayer expense. A good example is the Lotus Tower, a largely useless phallic shape, an emblem of Rajapaksa branding and political signage, which may take half a century to pay off at its current income.

A complex system, once set in motion, is hard to change. Its inertia is greater than the sum of all moving parts. And a city is a complex system. The chaotic interactions of a city are the bane of a central planner — but those chaotic interactions are what make cities interesting, and bring a welcome measure of serendipity to our lives. They make our self-built panopticons bearable.

The second approach might be considered science fiction. Of solarpunk, at that — a particularly curious branch of science fiction that, like Janus, manages to look both forward and back at the same time. Solarpunk makes living sustainably an act of rebellion in a world that demands it die out; it sometimes professes a fondness for a simpler past, and sometimes it projects a simpler past onto the skeleton of a future, but either way, it says: The current way of doing things isn’t working. Let’s try something else.

The story of Colombo is about how we arrange our cities and how we idolize the endless sprawl.

This is where we, perhaps, ought to pay more attention to materials and design. Our ancestors, for example, built with stone, mortar, and lime, and had roofs with clay tiles. Large houses had madhamidhul — courtyards — prominently influenced by Dutch colonists. Adding to ventilation were narrow, brick-sized slots higher up, where shade from the overhanging roof could prevent them from letting in too much heat.

Much of what we have adopted as modern architecture — concrete boxes, glass facades, Le Corbusier’s leftover aesthetics — was designed for cooler climates, for dwellings that had to retain heat instead of release it.

We can build in ways that make more livable cities — from large-scale design to small-scale material choices. And we owe it to ourselves to critically question design trends imported en masse from colder countries, and to gaze upon the chaos we create for ourselves and dream better.

There’s a story here. As Terry Pratchett would say, at the heart of it all, we’re not Homo sapiens, the wise man — we’re Pan narrans, the storytelling monkey. Stories bind us to paths leading to the future.

The story of Colombo is about how we arrange our cities and how we idolize the endless sprawl. Which is to say, Colombo’s story is about growth, fueled by the construction boom that followed the end of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009. The mismanagement of this growth has left even the basics of city planning behind. Many cities have some level of zoning in play — this area is residential, this is commercial, and so on. In Colombo, we don’t.

But like any story, Colombo’s can be changed — from growth to comfort. This requires the carrot and the stick. And to understand what might be a carrot and what might be a stick, we have to start with measurements.

As I’ve shown multiple times here, the idea of comfort can be measured, as the studies and self-propelled experiments described in this essay show. Air pollution levels, surface temperature, the ratio of green space to so-called gray infrastructure, or human-built structures, wet-bulb temperatures — these are easily measured with today’s technology.

Here’s a carrot, then. What incentives can we hand out for developments that improve on these things? Some things might work at the scale of large projects, such as requirements for maintaining public green spaces or shading proportional to the project’s size. There are even things that might work on a small scale: An experiment in Florida showed that low-income households are more willing to participate in rebate programs that encourage them to change their lawns to low-input, more environmentally friendly landscapes. The poor were willing; the rich, not so much. What we might have to do is spawn a veritable zoo of research around incentives, tied to methods that improve comfort for the whole.

The second step is to regulate: not ambitiously, but competently, and in an enforceable manner. Sri Lankan housing regulations are a bit of a joke; theoretically, there is a process of approval involving architects — but in practice, most people build first, without waiting for approvals. Corruption is rife within the system, of course.

It will be chaotic. Changing a story isn’t as neat and easy as dreaming up a radical new city from scratch.

Enforcing regulations for smaller homes might be immensely difficult. But larger-budget, high-visibility projects like apartment complexes, roads, parking lots, and office buildings already require more extensive approvals and a great deal more prep work than waking up one day and deciding to build an extra bedroom.

So, we regulate the visible. This is the stick. Large projects may be required to maintain a certain amount of greenery for the volume and area they displace, or to implement other schemes that help counter the heat. Maybe they contribute to an urban heat island effect control fund; perhaps they agree to maintain trees or shade along a set of roads nearby. Meeting these requirements can be incentivized; they can also be baked into the approval process.

It will be chaotic. Changing a story isn’t as neat and easy as dreaming up a radical new city from scratch; it’s tough to deal with so many people, and the idea of comfort will need to be thoroughly tested, its methods of observation worked out to be as fair as possible while erring on the side of whatever chips away at the urban heat island effect. But done right, we might encourage petri dishes of experiments that can be observed, scaled up, and implemented elsewhere.

Colombo isn’t unique in this story. Much of the world I’ve traveled and worked in also fits this description: Cities in South and Southeast Asia, trapped under the relentless need to develop rapidly, to cater to large populations with barely enough time and money to build infrastructure. Famously, New Delhi — a city of dense smog and Kafkaesque traffic jams — needs to build 700 to 900 million square meters of urban space annually just to keep up with the continuous influx of people. That’s adding a new Chicago every year.

We might not have the budget or the political will for a “ministry for the future.” But with knowledge, with stories, we might end up with a million smaller such ministries, each trying out different things, stumbling upon old hacks, discovering new ways, exploring all the dimensions of change. And, as long as we’re heading for cooler, more walkable, more livable cities, it might be worth stumbling along. Indeed, I’d say it’s necessary.

Yudhanjaya Wijeratne is a data scientist, science fiction novelist, and tinkerer from Colombo, Sri Lanka. He is the editor-in-chief of Watchdog, a research collective for fact-checking, investigative journalism, and community tech. One of his essays was published in “Climate Imagination,” from which this article was adapted.