Frank Gehry and the Art of Drawing

Editor’s note: Everyone knows the distinctive curves and lines of Frank Gehry’s buildings. But where do they come from? Gehry, who died this week at 96, described drawing as his way of “thinking aloud.” The following essay, excerpted from “Gehry Draws,” explores how his loose, searching sketches informed the architectural language he became known for.

It is well known that the design phases of Frank Gehry’s architectural projects are worked out through numerous models constructed from a wealth of materials, such as paper, cardboard, Styrofoam, and wood. And it is equally well known that it would be impossible to construct the complex spatial bodies that result from that process without calculations made by computers. It is less well known, however, that Gehry draws incessantly.

This is not unusual. There are 20th-century architects who have produced great and most diverse drawings, but others, like Walter Gropius, for example, neither wanted nor were able to draw. Drawing and architecture do not necessarily go hand in hand. In Gehry’s case, the use of drawing is not a question of ability, nor really a conscious decision at all. Rather, in its interplay of thinking and hand movements, drawing is the creative ferment of his goals, so that drawing should be considered as much a part of his calling as architecture and sculpture.

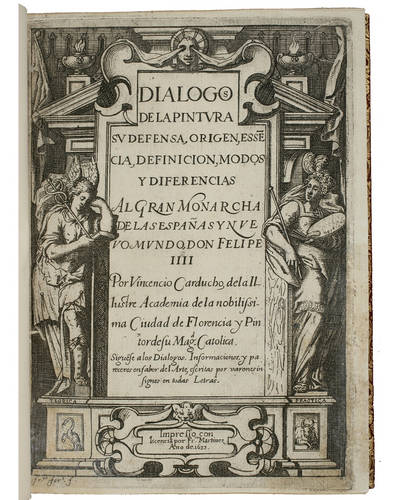

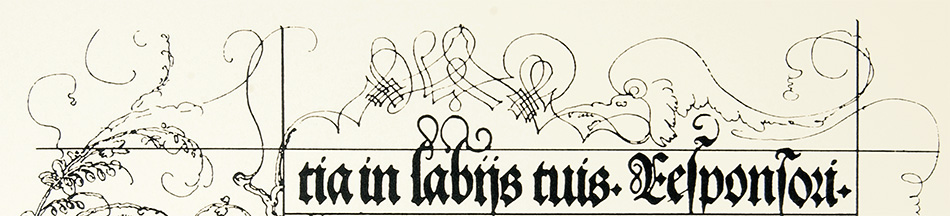

When Gehry was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1989, he confessed: “In trying to find the essence of my own expression, I fantasized the artist standing before the white canvas deciding what was the first move. I called it the moment of truth.” In paying homage to the application of the first line to a blank surface, Gehry was employing one of the oldest metaphors for the creative process. Countless treatises on painting — Carducho’s “Dialogos de la pintura,” published in Madrid (fig. 1) for example — discuss the approach to that crucial first stroke. A symbol of a self-referential art, which conceals within itself every conceivable formal possibility, the brush paints its own shadow falling downward to the left, an action triggering a decision that determines all the subsequent steps.

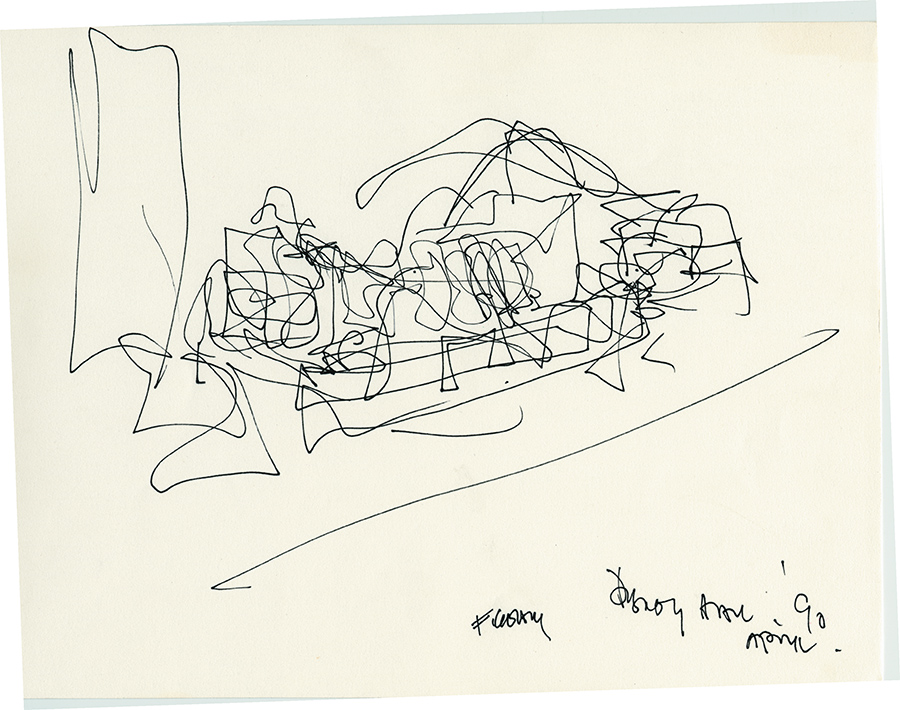

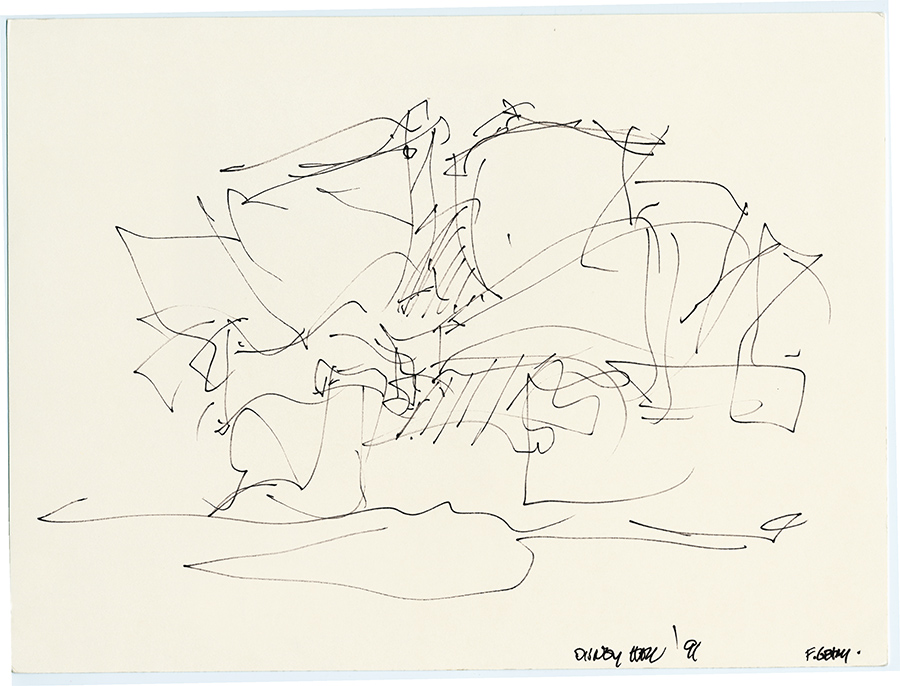

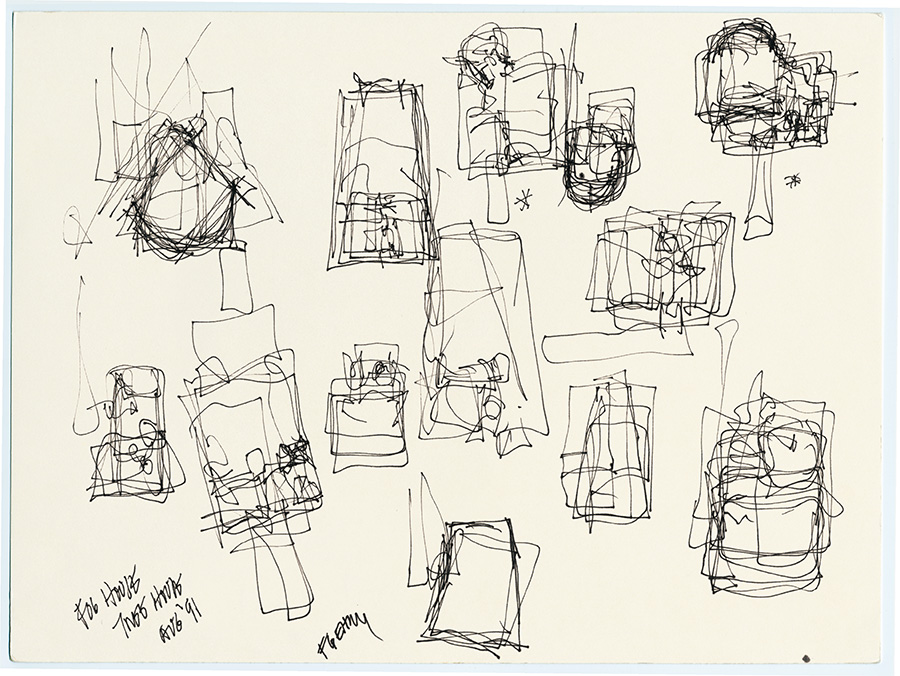

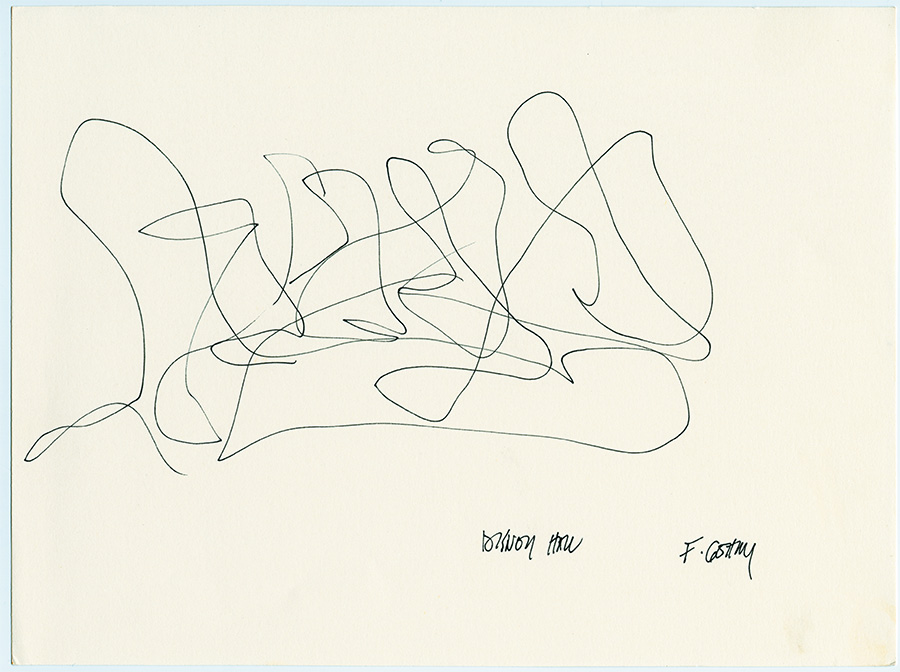

Subsequent versions of drawings by Gehry isolate or integrate the crucial fundamental lines [Grundlinie], as Gehry builds the tension between the white sheet, the first stroke, and the lines that follow. For example, one of the sketches for the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (fig. 2) programmatically reveals the initial line to be a liberated S shape. In another sketch for this project (fig. 3), three somewhat less isolated fundamental lines transform themselves by way of protrusions, wave shapes, and sharp bends into the curving, angular shapes — free in two dimensions, yet spatial in their crosshatching.

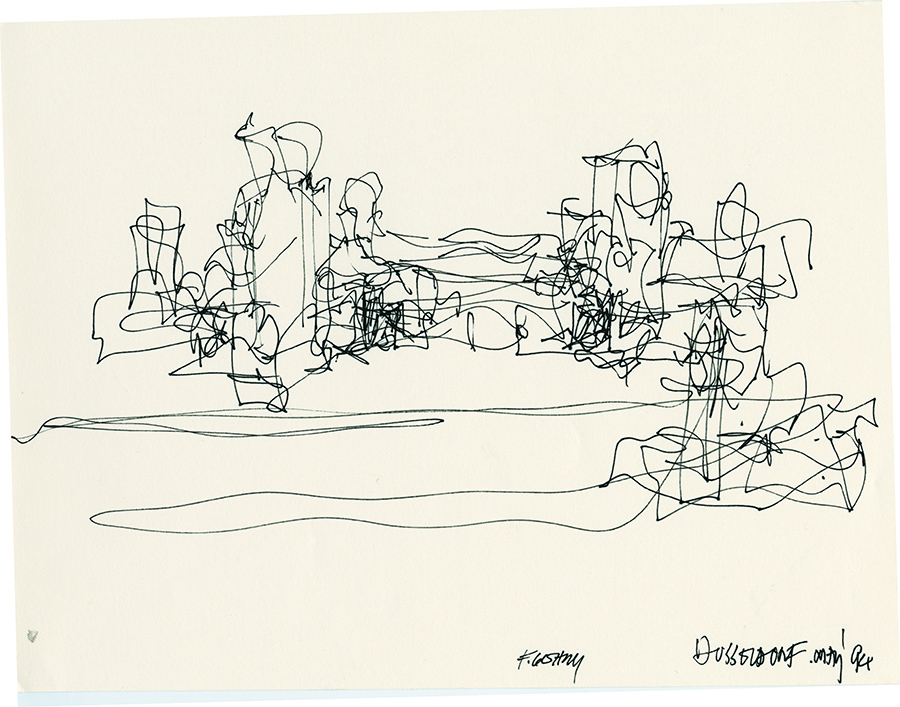

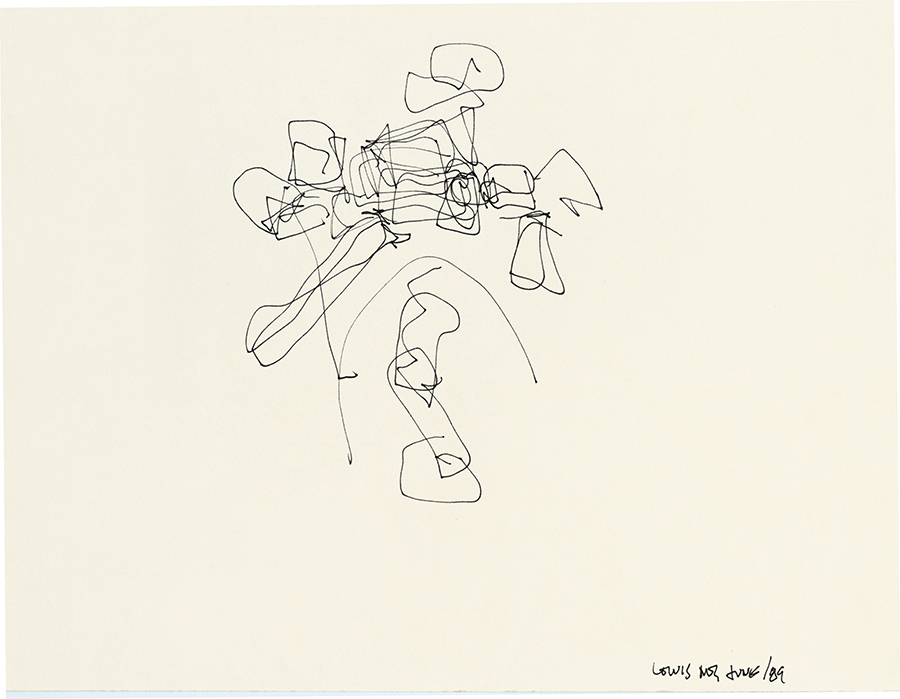

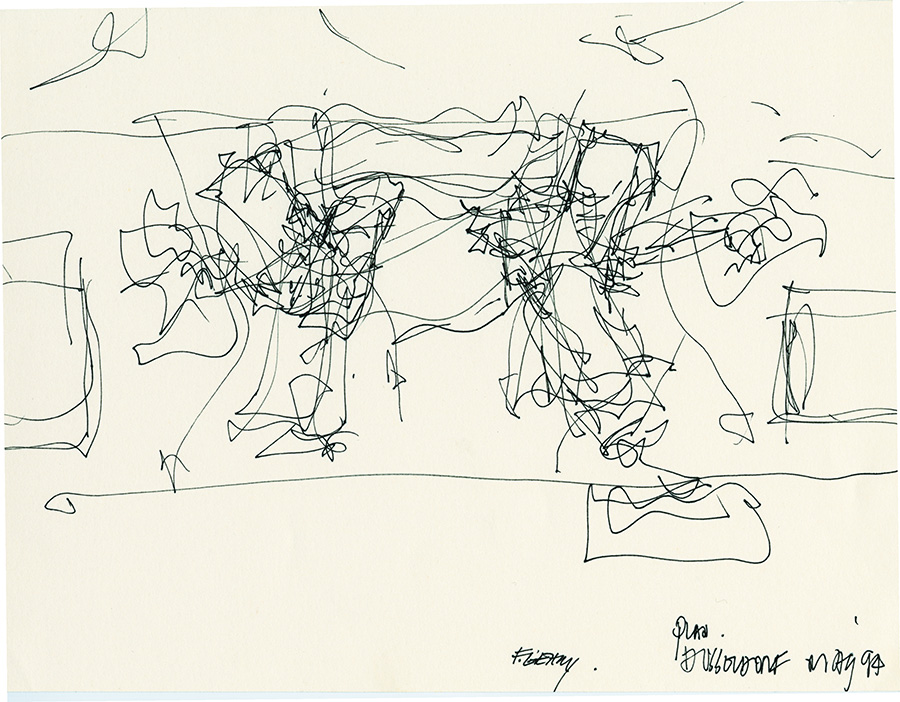

In one of the drawings for Der Neue Zollhof in Düsseldorf (fig. 4), these fundamental lines —horizontal forms that swing back and forth to open up into narrow surfaces — are connected to the building. Finally, the h-shape that leans diagonally to the left in a sketch of the Lewis Residence (fig. 5) is a form-constituting fundamental line integrated into a shape that not only suggests a landscape or a geological situation determining the ground plan but also evokes a mobile.

Tracing these variations on the “first move” of painting make it tempting to evaluate Gehry’s drawings in terms of the degree to which they are freed from an operative purpose. From the work of Giambattista Piranesi to the early Daniel Libeskind there has indeed repeatedly been a separation of architectural drawings from concrete building tasks. For example, Erich Mendelsohn, who may be considered one of Gehry’s most important inspirations, produced “architectural psychographs,” sometimes based on impressions derived from classical music, that lacked any reference to specific architectural projects.

Nevertheless, detaching Gehry’s drawings from the Hell of Purposes to make them products of the Heaven of Freedom would be a fundamental mistake. After years of experience with construction drawings and perspective views, the conditioning factors of terrain, of statics, and of means come so naturally to him that they are already integrated, even if they are not obvious at first glance. If the “first move” of painting formulates the primal conflict between constraint and freedom, it represents in a general form that which characterizes architecture in a particularly pointed way. In this respect, Gehry’s drawings are intertwined with every planning stage. From the first moment through the final state, and afterward as a reminder of the built complex, they help to fix still unfamiliar ideas, to grasp the essence of the stages of modeling, to free them from ossification, and to formulate new alternatives.

Gehry’s drawings are therefore a fully valid part of the history of the art of drawing, not because they have been freed from their architectural calling, but because they embody this tension between constraint and freedom. And Gehry’s confession that at the outset he is always like a painter before a white canvas should be understood in this sense.

The Framed Image

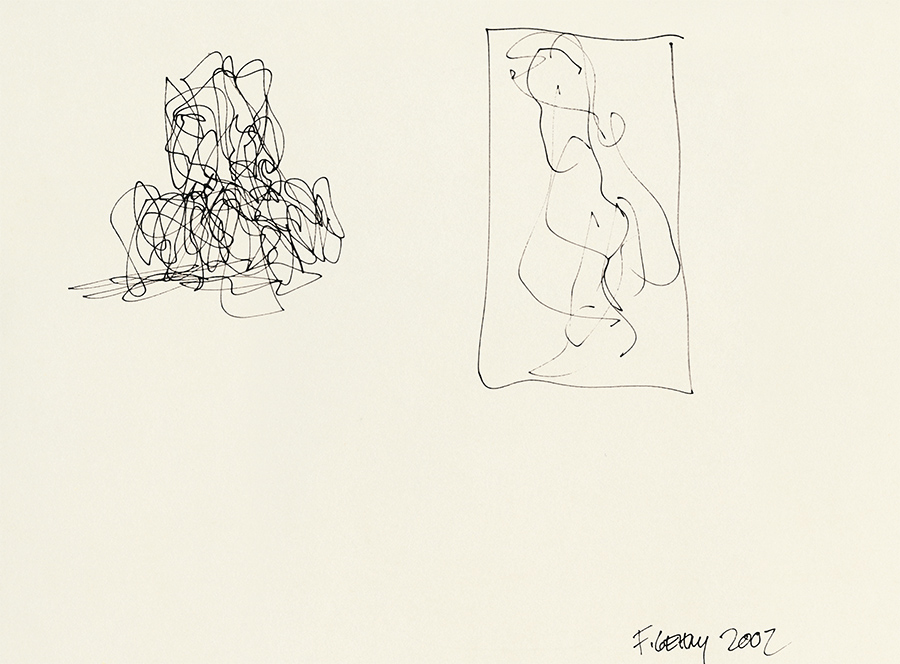

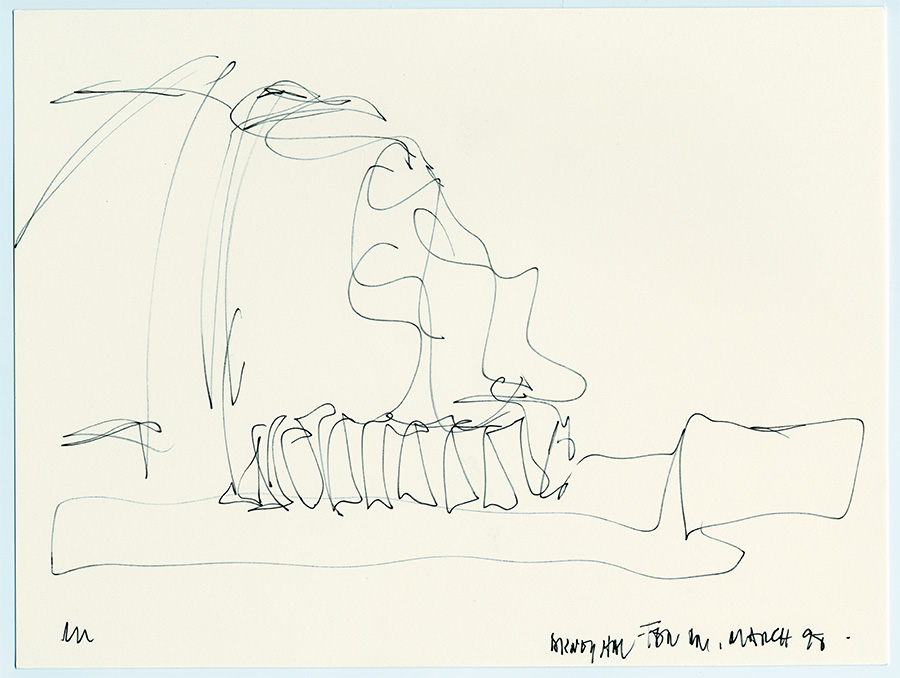

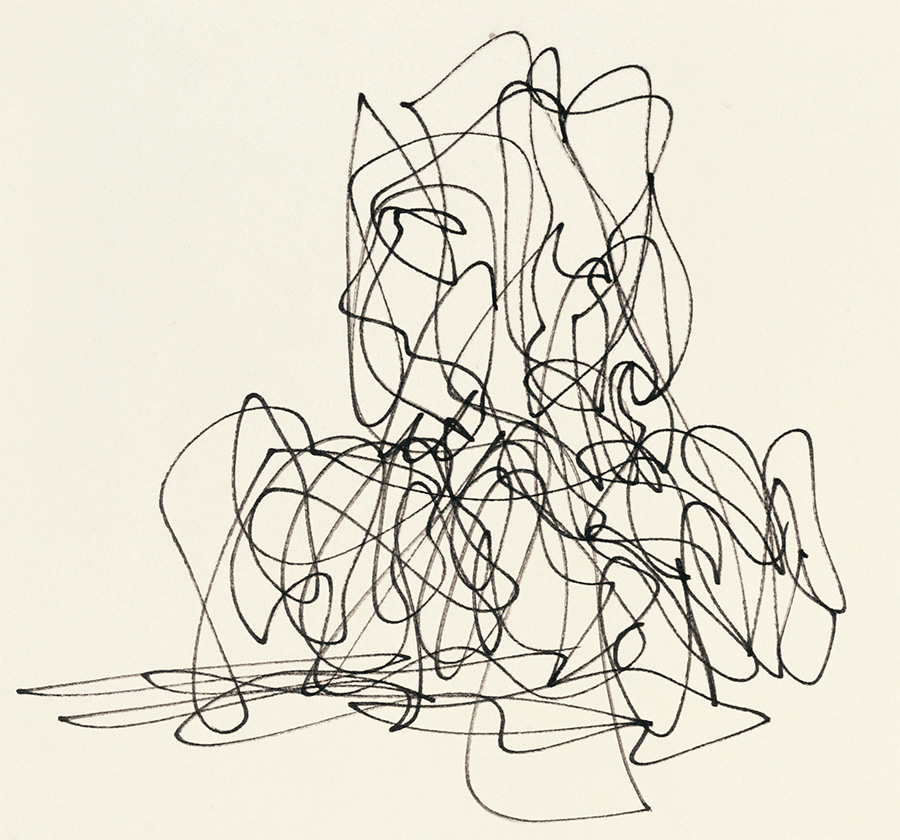

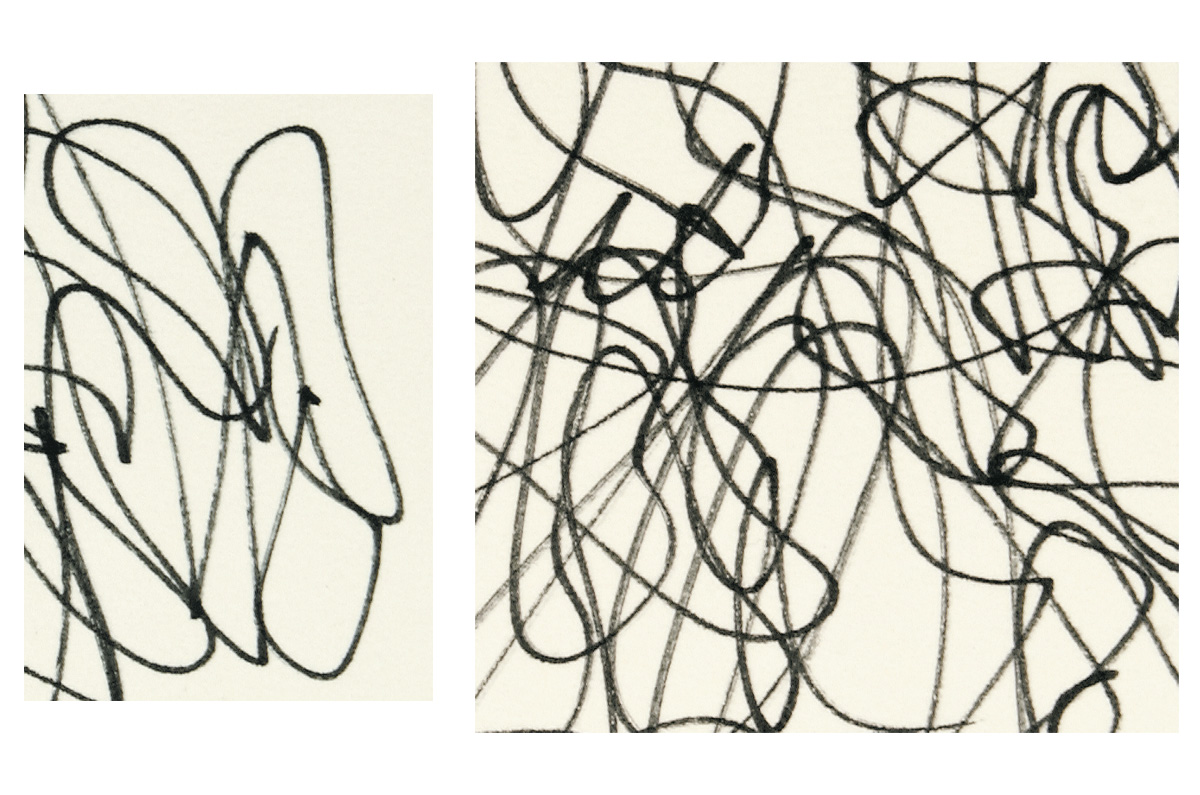

In 2002, in order to elucidate his drawing technique, Gehry made a sample sheet: He drew two sketches in black felt-tip pen on the same thin white card that he has used for years for his drafts and studies (fig. 6). Differences in placement and technique make the two drawings so crucially distinct that they clarify not only characteristics of Gehry’s own manner of drawing but also the fundamental motivations of architectural drawing in general.

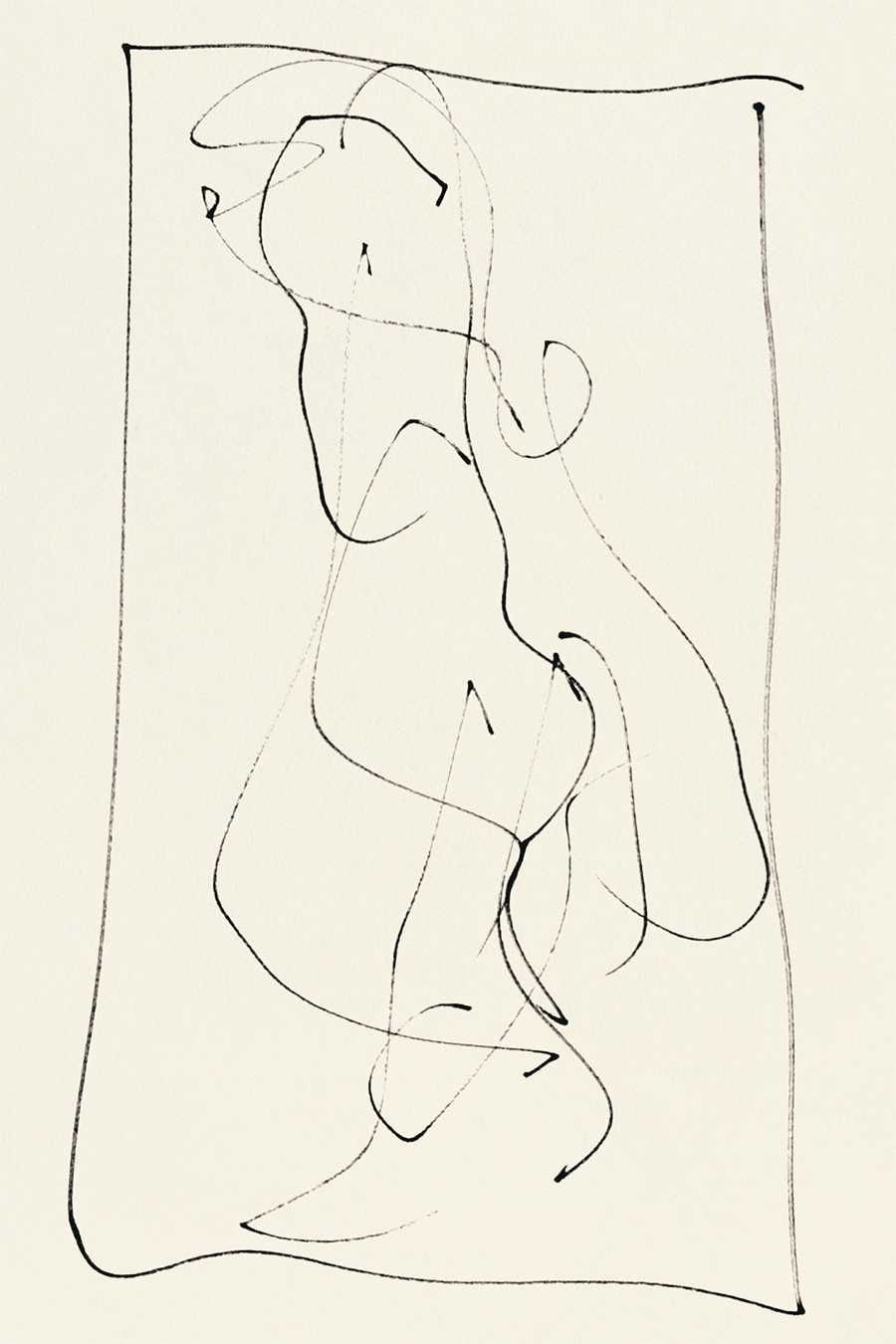

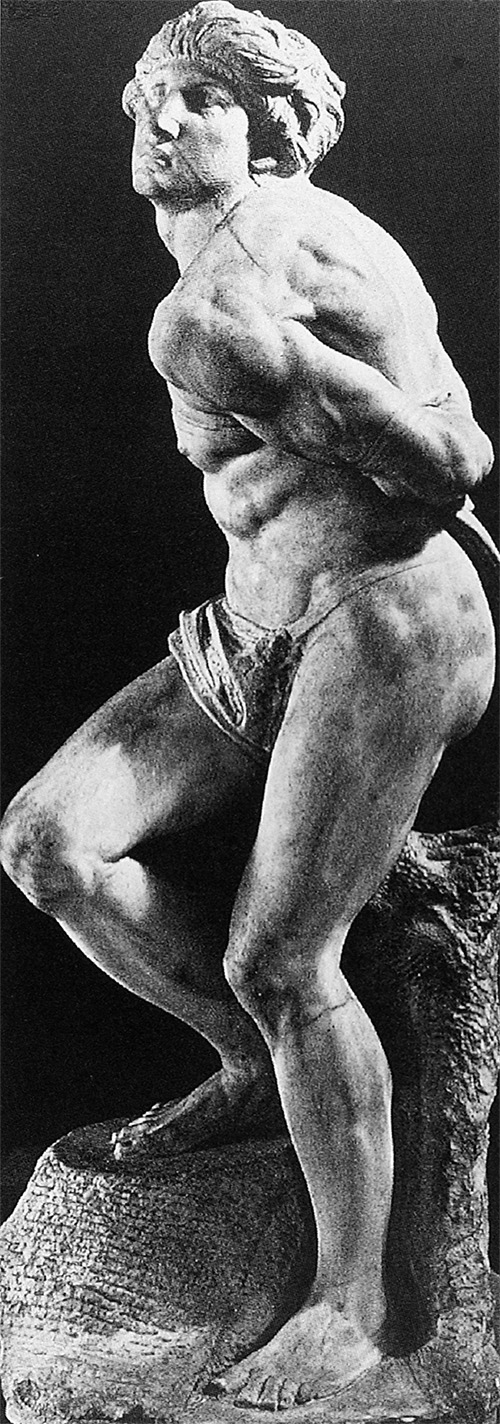

One difference between the sample sheet’s two shapes that immediately strikes the eye is that the form on the left is placed on the ground without a frame or base, and thus seems to be an undefined, atopic presence, whereas the one on the right has a frame and is thus defined as a picture. The framed sketch (fig. 7) relates to Michelangelo’s “Rebellious Slave,” which is now in the Musée du Louvre (fig. 8).

With its lines of different length, each starting anew, this sketch has its source in a free motion in which the whole arm participates, creating an impression of oscillation. Filling out the space to the upper and right edges, the diagonal orientation of the upper part emphasizes the inclination of the compact upper torso of the sculpture. The line that runs diagonally from chest to back is tangled, to suggest the fetters against which the body presses. An arc that curves back at lower right suggest the buttocks, while the curving lines in front indicate the drapery over the genitals and the balanced poise of the legs.

Drawn from memory and intended to capture the essence of the sculpture, these eight lines, running parallel or intersecting and playing with one another, exploit that fundamental principle of drawing according to which no mark is made until pressure is put on the pen, but without movement all that remains is a single point. Gehry’s individual lines range from those that have a powerful density to frail, diluted dots. Thus the sketch also elucidates the speed at which the lines were applied. Drawings are executed according to a rhythm that cannot be planned, alternating between acceleration and deceleration, rapidity and hesitating control, followed by pentimenti. Gehry’s eight lines are not corrected anywhere, and their smooth flow illustrates the constant speed with which they were drawn. Consequently they are products of an unprogrammed way of thinking whose statements, as unmistakable as handwriting, are inimitable.

The Universal Line

Even more revealing are the composition and style of the eight lines, which pass through 11 more or less well-defined S curves, characterized, as if by mottoes, by the lines sketched in the upper left and lower right corners. These S forms, which are only one element of Gehry’s highly complex arsenal of drawing techniques, can be taken as an example of the semantic wealth that is encapsulated even in seemingly unspectacular motifs. These curving lines offer themselves all the more as an example of Gehry’s manner since they run through his entire oeuvre of drawings. In contrast to the sketch for the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which isolated this form within the drawing (fig. 2), another drawing of this same project (fig. 9) plants the S shape in the middle of the building, as if it were at once its heart and its springy hinge.

These lines are part of a chain of efforts, stretching far into the past, to obtain a single pictorial formula for movements in nature and in thought. The naturalness with which Gehry uses this formula is the result of centuries-old reflection on this problem (not just in art but in philosophy and science as well) that informs this shape.

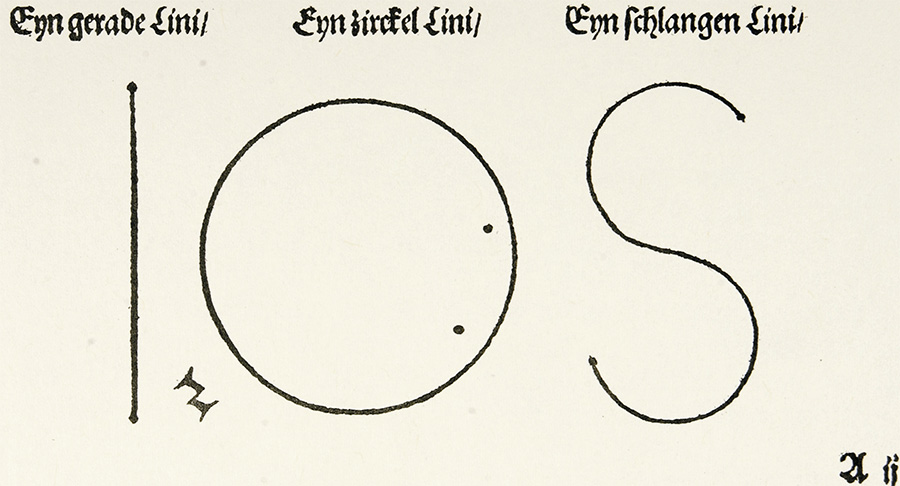

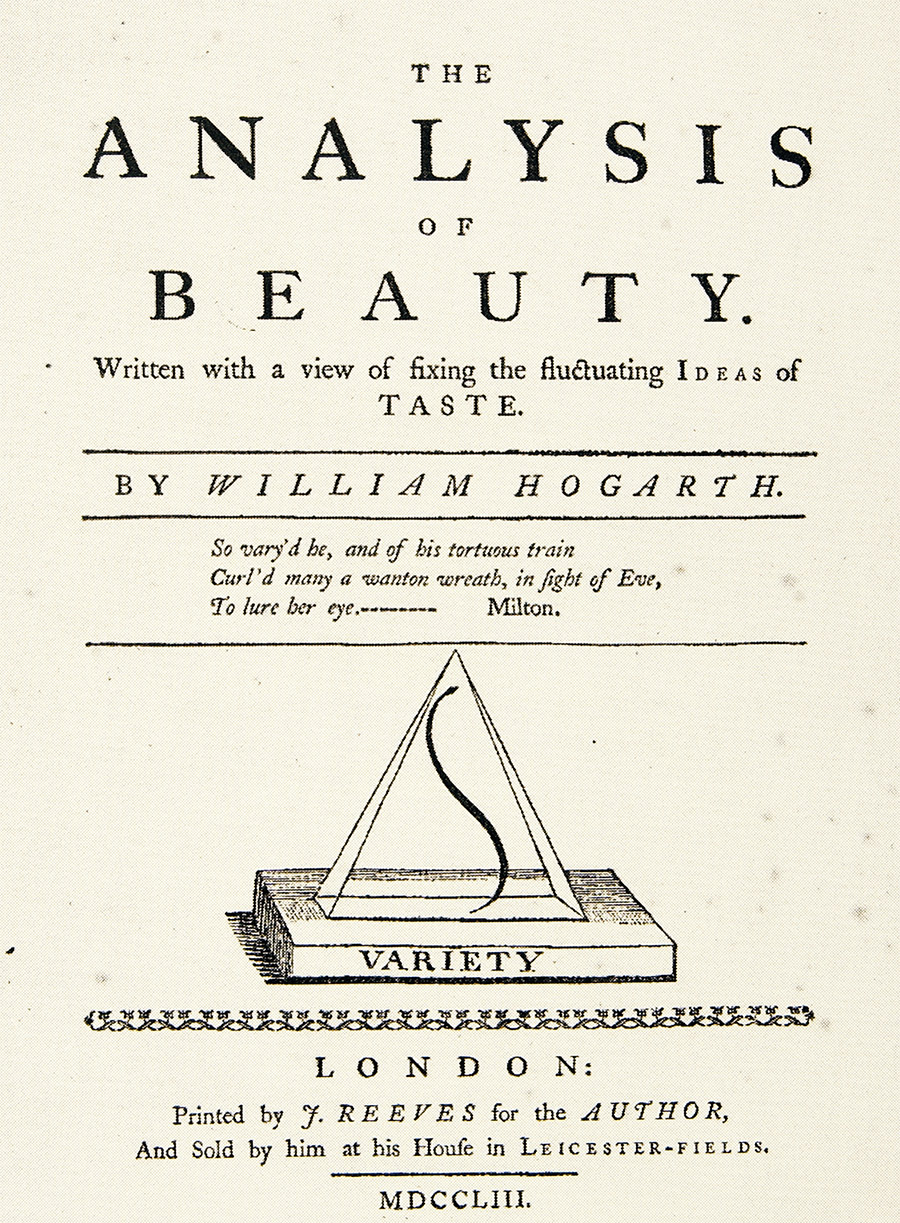

The idea of the serpentine line can be traced back to Leon Battista Alberti (1404‒1472), who compared the movement of hair to that of flames and snakes. This image was so suggestive that both the serpentine form and the flame became symbols of the creative line that stimulates the imagination. For example, in his “Unterweysung der Messung” of 1525 Albrecht Dürer asserted that the serpentine line perfectly embodied the dual purpose of drawing — both pointing back to nature and revealing the mind — because it could be pulled back and forth “according to one’s wishes” (fig. 10). After a series of analogous applications, in 1753 William Hogarth fixed the serpentine “variety” within a prism as the symbol of the summa of all forms of movement and depiction (fig. 11). And a good hundred years after Hogarth’s line of perfection the chemist August Kekulé picked up the topos of the serpentine line as art theory’s image of mobile nature and applied it to the sciences as well. Even the abstract model of the double helix created in 1953 by the artist Odile Crick seems to feed on the tradition of the S line.

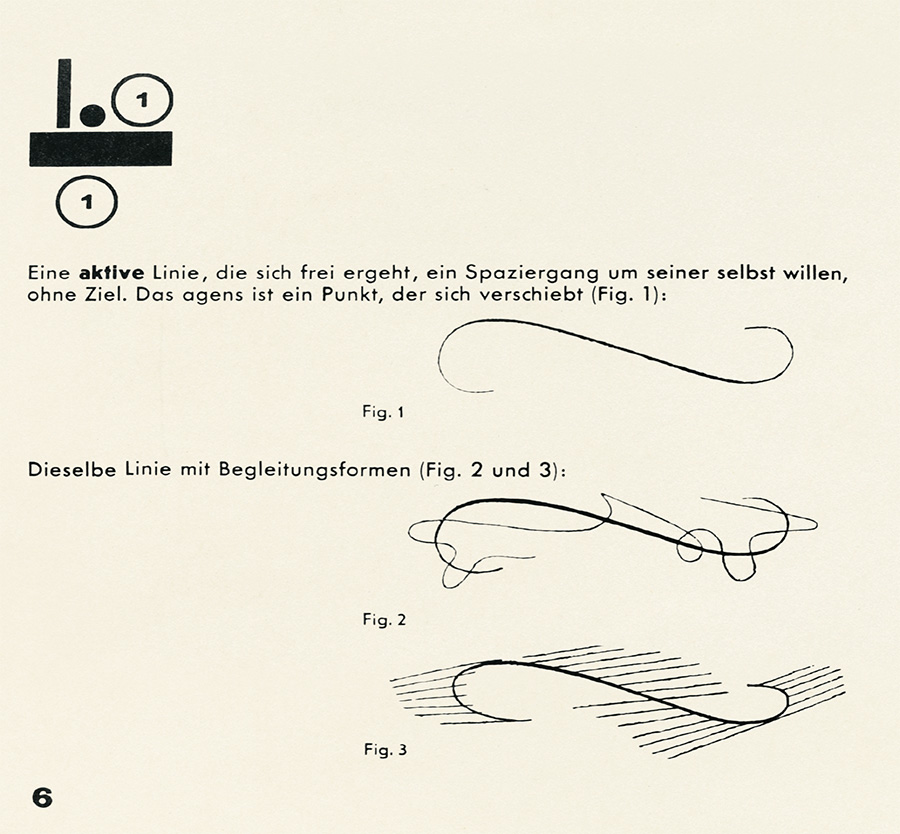

The validity of the linea serpentinata has not gone undisputed, and there have been repeated efforts to turn contour into the atmospheric effect of zones of spatial and misty light found in Impressionism. Because an art form without contours lacks the line’s double quality of being extremely precise as a line in motion while still permitting freedom, the artists of Expressionism and Fauvism, to say nothing of Art Nouveau, rehabilitated the contour line. Paul Klee assigned the serpentine line in particular to the highest rank of motoric energy for subsidiary lines, hatching, and self-twisting: “An active line on a walk, moving freely, without goal. A walk for a walk’s sake. The mobility agent is a point, shifting its position” (fig. 12). Developing Klee’s idea, Gilles Deleuze characterized the folds of the baroque and Klee’s serpentine lines as the essence of creative thought — an observation that had an enormous influence on architectural theory in the 1990s.

This return demonstrates the power of a universal form that Gehry developed independently, reflecting on the early drawings of Erich Mendelsohn, for example, which the latter first exhibited in Paul Cassirer’s gallery in Berlin and then pursued in his “Dune Architectures.” The sketches by the architect Hermann Finsterlin also stand in a tradition that Gehry’s draftsman-like, imaginative intelligence brought to a unique and unmistakable stage in the shaping of internal and external movement.

The Model of the Museum of Tolerance, Jerusalem

In contrast to the rather planar sketch of Michelangelo’s “Rebellious Slave,” the figure on the left side of the sample sheet (fig. 13) has a stronger spatial presence. The impression of depth is the result of applying the strokes in a single uninterrupted gesture, within the radius of a supported elbow, through a series of circling and spiraling movements. The unfolding of this form reveals the spatial quality of Gehry’s touch, which gives the form depth by continually circling and curving anew, bringing the elements of the S form into an organic continuum.

With no external borders or foundations, the shape floats in space without referent. Although the two loops at lower left that point outward might suggest a shadow falling on a plane, the dominant impression is of a two-tier form rising up without being tied to any ground. Above a cylindrical pedestal looms a tower that seems, at first, to be lashing itself in and is hardly less articulated and folded than the lower story. This is a sketch for the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem.

The uninterrupted line of the architectural model has its starting and ending points at the far right of the lower story (fig. 14). The curving, circling, scythe-like bending, eddying, meandering, and above all snaking lines produce a plexus in the interior (fig. 15), but their cumulative effect suggests vibrating, pulsing forms. This contrast reveals the crucial nature of architectural drawing.

The idea of “architecture as image” evolved from Ferdinando Bibiena’s stage designs and the architecture parlante of French architects. By contrast, Carl Linfert’s still unsurpassed theory of architectural drawing — without which Walter Benjamin’s conception of “distraction” would scarcely have been conceivable — resolutely emphasized that the physical shape of architecture can only be revealed successively; it cannot be assimilated in the single image alone. Interactions between architecture and bodily movements yield sensory events whose contingency eludes both static images and images that permit a simulated walk-through. This determination also defines the limits of central perspective, which relates the work of architecture to a single possible viewpoint. Perspective, which almost immediately came to dominate the construction of images in two dimensions, was employed in architecture far more hesitantly; even the Bauhaus rejected vanishing-point perspective in favor of axonometric renderings, so that buildings would not be fixed according to a particular point of view. Working against this sort of objective alienation, Gehry’s drawings do not attempt to tailor the building to the subjective viewer but instead try to conceive the autonomous objectivity of the building in the viewer’s imagination as a sum of possibilities. Hence his drawings avoid contours to which the lines projected from vanishing points could attach.

In a second drawing from 2002, a side view of the museum in Bilbao appears below an aerial view (fig. 16). Above the fundamental line of the lower figure is a single stroke that unfolds a continuous movement through Euclidean space, connecting the side and ground planes and rotating them into the third dimension. This quite commonplace method of projecting a side view and a top view into a single plane takes on an unusual quality in Gehry’s work: Although each shape is connected to the other by two lines, the side view is shifted to the right relative to the top view, by about a third of its length. This not only tips the building on its side toward the viewer but also makes it seem to spiral in space.

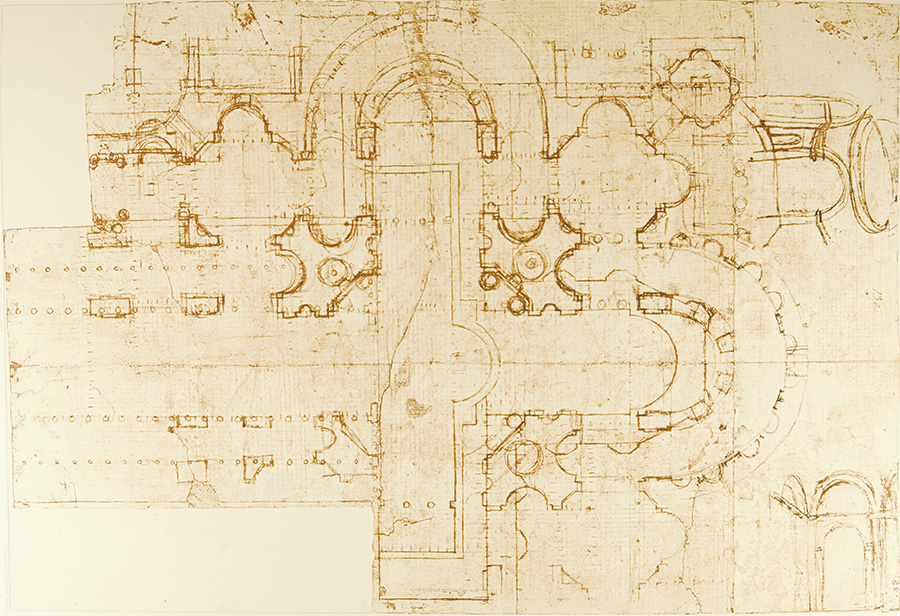

In their combination of different points of view and in their groundless and frameless indeterminacy, Gehry’s figures conform astonishingly well to Linfert’s call for an “unconstrained indifference of the foil” that avoids locating the building pictorially. If parchment — which has no fixed ground and whose translucent appearance seems to sublate the underlying surface, as it were — is the appropriate foil for architectural drawing, as, for example, Bramante’s magnificent floor plan for Saint Peter’s in Rome demonstrates, then Gehry’s drawings appear as though they had been sketched on parchment. Offering neither the certainty of the mathematical point of view nor the pictorial fixing of a ground, they show the models as the motoric imagining of the building’s entire complex. The sketch for the Museum of Tolerance (fig. 13) is exemplary in this sense because it avoids not only the simplifications of perspective but also the deficiencies of the visual. As an atopic dream shape, it imagines an architecture in a form that attempts to sublate pictorial reduction.

By juxtaposing on the sample sheet the framed image with the liberated architectural model (fig. 6), Gehry complies with the divergent agendas of two- and three-dimensional shapes. On the right, a sculpture is brought within the plane of a drawing by means of eight variations on the serpentine form; in the shape on the left, the single uninterrupted line creates an imaginary space out of circles and spirals, leading to the objective self-representation of architecture as the dream shape of the thinking hand.

Composition

The arrangement of the two figures on the first sheet makes it evident, thanks to its clear compositional principle, that Gehry is employing the transition from the image to the haptic imagination as a structural principle in all his drawings. Axially aligned, the figures appear in calm isolation, and because they are shifted slightly into the upper half of the sheet and displaced a touch to the left, the signature at lower right offers an optical point of orientation. Analogously, in the sketch for the Bilbao museum (fig. 16) a convulsion of lines is added at lower right to establish a contrapposto with the signature and thus balance the overall composition.

The history of drawn architectural models is filled with ground plans and perspective details that overlap and start again anew, as can be seenfrom one of the most enigmatic of examples: Bramante’s Uffizi-20a-plan for New Saint Peter’s in Rome (fig. 17). But even when his drawings fill the entire space, as with this sketch for his own house (fig. 18), Gehry allows the individual motifs to speak in isolation, permitting him to capture the self-determination of every architectural model in its totality, which transcends the image. In terms of composition his sketches retain a visual equilibrium, which lends a gentle rhythm to the tension between abundance and emptiness. In populating his sheets Gehry shows respect for the individual value of even the tiniest details. Each of his figures retains a halo of respect, protecting the presence of the building from the overlapping that becomes possible in its image. Thus Gehry’s compositions also illustrate an effort to preserve in the image architecture’s ability to transcend the pictorial.

The Line’s Autonomous Course

Gehry’s principle of positioning the imagination in order to allow it to wander freely is also evident in the first sample sheet (fig. 6), where both figures move along the border between abstraction and recognizable motif. This is because, while the overall form may permit us to discern a purpose, the activity of the lines follows its own inclination, which obeys inherent, independent laws and energies. Both figures give the impression that the draftsman was observing himself in the act of drawing. He becomes the object of their autonomous course.

This is the principle of the ceaseless scribbling, sketching activity of the hand, which Leonardo da Vinci, as an obsessive, was probably the first to employ. The pleasure Parmigianino took in allowing the stroke of his pen to be guided by the curving line, until the lines broke free of the content and began to oscillate freely, also helped to establish this tradition.

Dürer, however, gave it a particular stamp. The marginal drawings in “Das Gebetbuch Kaiser Maximilians I.” of 1515 are among the most valuable objects in the art of drawing, because here Dürer is at play, toying with ornaments, letters, and figures; he forsakes all semantics and embraces the principle that the creative imagination propels itself. Along the image’s upper edge are perpetual metamorphoses of vertical or horizontal S lines that, because of their indomitable mutability and interpretability, form an organ of the creative urge (fig. 19). It is as if they had taken Lucretius’s immortal evocation of the constantly mutating form of clouds and translated it into drawings: “Forming themselves in many ways, aloft, / Changing incessantly, fluent, volatile.” To the extent that nature itself is the generator of the images, it is one model for Dürer’s protean gesture: the theme enunciated by his highly artistic shapes is the stochastic effect of forms that seem to come arbitrarily from outside.

The courses of Gehry’s dynamic lines, which come together into an overall form seemingly against their will, offer a cosmos of related webs: this becomes clear, for example, if one superimposes one of the drawings for the Walt Disney Concert Hall (fig. 20) with the cross-hatching of a sketch for Der Neue Zollhof in Düsseldorf (fig. 21). Gehry belongs to a line of outstanding draftsmen for whom the creative principle does not involve, for example, the artist revealing himself as the lord of his creation: instead he controls the course of his imagination’s motor activity as if from the perspective of an observer. His drawings remain tied to construction, but they push us into regions devoid of articulated ideas. Therein lies what is perhaps their most important calling: not to obey their creator but to astonish him. In contrast to the great architectural drawings of Zaha Hadid, for example, who develops her shapes by means of a highly geometric, constructivist, and — for all their splintering — Ciceronian gesture, Gehry’s drawings are subtly Epicurean, as it were: they yield to the ideas and circumstances that affect a form. In contrast to a constructivism that turns perspectival or axonometric forms into brilliantly constrained shapes, Gehry’s figures preserve a subtle joy in a metamorphic dynamics.

Chance as a Principle of Form

Chance is also part of this motor activity, offering, in nature and in everyday life, an inexhaustible source for the powers of the imagination. In accordance with ancient theories of chance sources of inspiration, Alberti associated the artistic imagination with the ability to perceive lines, lineamenta, in irregular objects, like clumps of earth, which by means of slight alterations could then be endowed with a form, their shape perfect and complete. In mere spots on the wall Leonardo saw entire cosmoses of designs for paintings, indeed he endorsed Botticelli’s method of throwing a sponge soaked with different paints at the wall in order to obtain spots as a source of inspiration for landscapes, and even extended it to every other conceivable subject, such as battles, seas, clouds, and forests. By way of Alexander Cozens, who called his landscapes “a production of chance, with a small degree of design,” this principle continued to have an effect through such aleatoric artists of 20th-century art as Hans Arp and John Cage.

Gehry took it up in his own way. He takes chance not as an absolute principle but as an opening that frees him to react to unintentional forms of both the quotidian and associative arrangements, as well as the uncontrolled movements of one’s own thoughts. Already in Dürer’s marginal drawings, whose very value neutralizes the hierarchy of main and subordinate theme, there is a nonhierarchical mechanism at work that liberates the imagination from the strict meaning of the motifs.

The theory of chance images applies this method to the sources for the artistic imagination. Gehry’s drawings correspond to the curves of Dürer’s marginal lines as well as to Alberti’s systems of clumps and Leonardo’s sponges tossed against walls. As architectural drawings, they are never free of an awareness of the possibility of their realization. They do not constitute an immediate means of translation but instead an artistically created primal matter that stimulates the imagination like a gift from nature.

Drawings, like every form of art, must be understood in terms of their historical period, but they possess a dense, almost anthropological proximity to the ideas that formed them, so that they have an inherent, timeless modernity. When faced with drawings by Bosch, Callot, Tiepolo, Menzel, or Mendelsohn, viewers are so astonished by their immediacy that for a moment they forget these works derive from other ages and cultures. Gehry’s drawings belong to this same sphere.

The Problem of Drawing

Drawings are among the ephemeral products of the visual arts, but the frailty of their physical constitution is not a shortcoming; rather, their reduced materiality possesses a force that drives the imagination, which itself can overcome possible inhibitions. Among the strangest aspects of the human capability to perceive and process is the power of drawings, at times more powerful than stone. Onofrio Panvinio recounted the story of Bramante persuading Pope Julius II to tear down the Constantinian basilica of Saint Peter’s, an act as incomprehensible in 1505 as it is now: “He showed the Pope now ground plans, now some other drawings of the building, never ceasing to plead with him, ensuring that the project would bring him supreme fame.” The enormous late antique church was knocked down, because the imagination could not bear seeing its drawings go unrealized.

Describing this phenomenon in the language of art theory, Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) extols the superiority of the line over the building:“The designs for the latter [architecture] are composed entirely of lines, which for the architect is nothing less than the beginning and end of this art, for what remains to be communicated by models in wood, derived from these lines, is nothing but the work of stonecutters and masons.” The Neoplatonic, antimaterial basis of this argument would be alien to Gehry, but he would underscore the high regard for drawing in terms no less resolute.

Recent decades have been filled with a technical euphoria that has led some commentators, and even architects, to speak of the end of craft skills and all forms that are not technically mediated. Since, from the initial stages, the computer helps to lend ideas material form by calculating the spaces and statistics, and since it also makes sculptural models consistent by means of scanning processes, it has in fact taken over or replaced many of the functions of drawing. In its indispensable importance, the computer has become, in the spirit of the mathesis universalis, the generator of forms it produces of its own accord.

The inwardly curving spatial bodies of Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao could scarcely have been conceived and built if they had not been simulated and calculated using a computer program designed for the aviation industry. However, the possibility of imagining spaces that go beyond the limits of the human imagination is, for Gehry, irrevocably based on the drawing hand. From the earliest planning stages to the digital CATIA, disegno is placed within an extended continuum, and the “first move” of the hand remains the metaphor for the ur-line that determines all the processes to come. The choice between computer and drawing is thus wrongly put. The drawing hand and the modeling hand can only be eliminated at the cost of losing the body’s direct input in the process of forming the model.

There are new opportunities there but also impoverishments so clear that we should not expect drawing — an instrument of thinking tied to the body — to be eliminated, even over the long term. Rather, there is an interaction with the most advanced technologies that obtains its productivity precisely by means of sharpening the distinctions between drawing and the digital line. The events of recent times have not meant the end of disegno but rather its perpetuation on two planes: as a product and a medium of both craft skill and technology. Gehry’s communication of technological possibilities by means of the motoric potential of the thinking hand, using every mechanical innovation, but not neglecting any manual technique that might aid the imagination, was and is, in its imperturbable freedom, the embodiment of the more sophisticated avant-garde.

The magic of architectural drawing led Vasari to consider it more enduring than stones. Gehry’s oeuvre is an exemplary case of the mysterious validity of this conclusion.

Horst Bredekamp is Professor of Art & Visual History at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. This essay is excerpted from the 2004 volume “Gehry Draws.”