The Prompt Engineer Is the Artist of Our Age

In 1839, the French artist Paul Delaroche reportedly looked at the first daguerreotype and declared, “From today, painting is dead.” He had seen the future, and like many who glimpse it too early, he mistook transformation for extinction.

Of course, painting didn’t die. It got weirder. Within a few decades, artists were flinging paint onto canvases, bending perspective, and painting clocks that melted like soft cheese. Freed from the burden of realism, painters dove headfirst into abstraction, expressionism, surrealism. The challenge of photography pushed painting toward its most radical innovations.

Today, we’re hearing a familiar lament, this time about large language models and other generative AIs. Will writers be replaced? Is human creativity obsolete? Are we all just one good prompt away from becoming irrelevant? The dread is palpable, especially among artists, poets, screenwriters, and others whose livelihoods depend on the ineffable quirks of human originality.

But if the history of photography teaches us anything, it’s this: A new tool doesn’t obliterate old forms. It reshapes and expands the creative landscape.

A new tool doesn’t obliterate old forms. It reshapes and expands the creative landscape.

In fact, I’d like to propose something that sounds almost heretical in certain artistic circles: Prompt engineering, the act of crafting input to coax a desired output from an AI, may soon be regarded as a legitimate artistic medium. In the same way photography became an expressive form in its own right, so too might the process of collaborating with an LLM become a canvas for creativity.

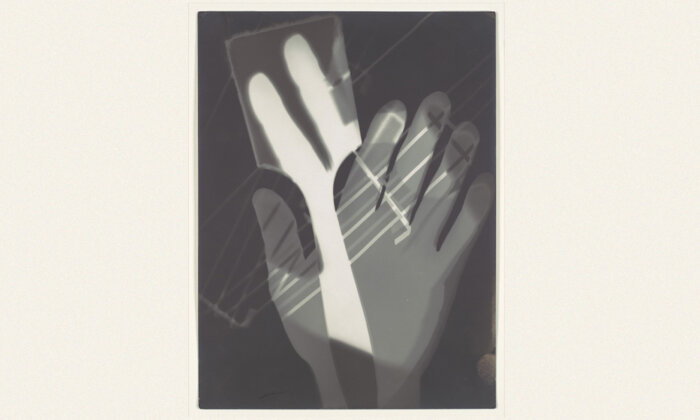

The Tool Is Not the Threat

The panic surrounding generative AI is not unlike early reactions to the camera. In the mid-19th century, many feared that photography would devalue the skill of the painter. The art critic John Ruskin dismissed photography as unworthy of artistic consideration: “Fine art must always be produced by the subtlest of all machines, which is the human hand,” he wrote. “No machine yet contrived, or hereafter contrivable, will ever equal the fine machinery of the human fingers.” But the medium matured. By the early 20th century, photographers like Alfred Stieglitz were producing moody, expressionist images that rivaled painting in emotional resonance. Stieglitz described his artistic process in poetic terms: “In photography is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality.”

The key lesson? The tool may be mechanical, but its use is not.

Today, the artistic prompt typed into a chatbot is itself becoming a form of expression. The difference between a clunky query and an inspired one is as wide as the gap between a finger painting and a Van Gogh. Ask an LLM to “write a poem about sadness,” and you’ll get bland, derivative, sentimental drivel. It takes skill and creativity (not to mention patience and iterative adjustment) to fashion a prompt that will produce something noteworthy — though when it comes to poetry, even that may not help.

Art Is a Collaboration

But artists have always relied on the tools available and often on collaborators. Painters experiment with new brushes, unconventional tools, or materials they didn’t invent. Photographers manipulate lenses and darkroom processes to achieve effects no camera alone could produce. Even Michelangelo had to design scaffolding that allowed him to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a technical solution essential to realizing his vision. Creativity has always been a mix of ingenuity, collaboration, and mastery of tools.

Similarly, most novelists benefit greatly from the contributions of their editors, just as most composers rely on other musicians to realize their creative visions. Creativity isn’t a solo act; it’s a dance between vision and medium. Prompt engineering is simply the choreography: choosing the steps, setting the pace, knowing when to lead and when to follow. As artist and AI collaborator Refik Anadol says, “This is pure collaboration , imagination with a machine.”

In this light, prompt engineering starts to look a lot less like automation and a lot more like improvisational jazz. It’s iterative. It’s expressive. It rewards playfulness and surprise.

New Medium, New Muse

Let’s revisit our exploration of the decades immediately after photography was invented, when artists stopped trying to compete with the camera and started doing what the camera couldn’t. Impressionism emerged, then Cubism, then Surrealism. Painters weren’t replaced; they were liberated. Similarly, as generative AI becomes more capable, human artists are already adapting by doing what machines can’t: embracing ambiguity, making conceptual leaps, using irony and humor with devastating precision.

As generative AI becomes more capable, human artists are adapting by doing what machines can’t: embracing ambiguity, making conceptual leaps, using irony and humor with devastating precision.

At the same time, some artists are leaning in. The world’s first AI art museum, dubbed “dataland,” will open next year. Poets publish hybrid works, disclosing the prompts that they used like chefs listing ingredients. Musicians like Holly Herndon are using AI models trained on their own voices to create harmonies that they could never sing solo.

Even this article was written with a healthy amount of AI assistance. AI helped me track down and verify quotes, suggested examples, edited my prose, and even proposed prose that I edited and incorporated into my argument. After repeated rounds of back-and-forth editing, it would be difficult to disentangle which parts of this article were written by AI and which were written by me. Indeed, doing so would be both quixotic and pointless, like debating whether the spellcheckers that caught and fixed my typos deserve authorship credit. I could not have written this article without AI assistance – my art history knowledge isn’t deep enough – and AI could not have written it without the impetus of the prompts I crafted to guide its output. The result is something neither of us could have created alone. AI opened up opportunities for expression that would not have existed in its absence. That, too, is a kind of art.

Let’s Not Fear the Future (Again)

Yes, there are legitimate concerns with the relationship between art and generative AI: labor displacement, plagiarism, deepfakes, algorithmic bias. These are serious issues that deserve serious regulation. But they are problems of governance, not intrinsic arguments against the medium itself. Just as the printing press enabled both Proust and propaganda, the camera both snapshots and surveillance, so too will AI produce both garbage and greatness. The answer is not to halt its use, but to elevate its practice.

The truth is, we’ve been here before. When film was invented, some thought that it would mark the death of theater. Instead, it led to productions that would probably never have been created for the stage, such as “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Lion King.” And those, in turn, inspired popular stage versions, reinvigorating Broadway. We can respect the old tools without fearing the new ones. And we can embrace the idea that human creativity isn’t solely defined by what we make entirely on our own, but by how we shape and are shaped by the tools we use.

If history is any guide, the prompt engineer of today may be the Picasso of tomorrow, except instead of brush and canvas, their medium will be language and logic, suggestion and subversion, a series of well-placed words and an eye for surprise.

Danny Oppenheimer is a professor at Carnegie Mellon University with a joint appointment in the psychology department and the department of decision sciences. He is the author of “Democracy Despite Itself.“