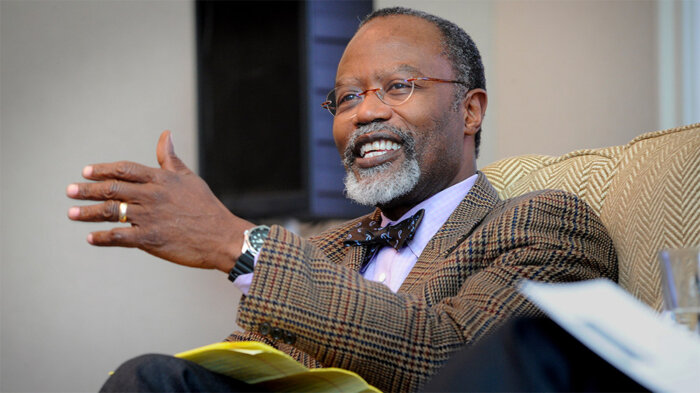

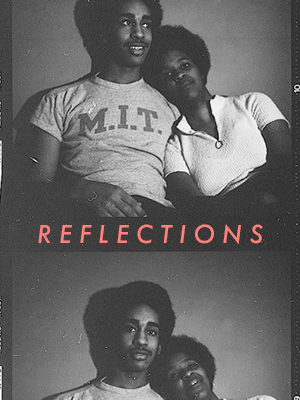

Phillip Clay: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT

Edited and excerpted from an oral history interview conducted by Clarence G. Williams with Phillip L. Clay in Cambridge, Massachusetts on January 23, 1996.

I was born and grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, and I was there through high school. I had sort of a regular segregated high school and a regular life. My clearest early ambitions were that I would go to some of the places I read about in magazines. That was during the late ’50s and early ’60s. I graduated from high school in 1964.

Our high school was, by the then standards of segregated education, a very good high school. It had a college preparatory track, and students were identified for that track in the sixth grade. They were then directed toward elementary schools that featured the advanced academic programs, starting in the sixth or seventh grade. Then, in high school, I was on a track that emphasized college preparation. I had geometry, chemistry, trig, biology, extra semesters of history, and foreign language.We had lots of activities. I was active in student council and various service organizations. In junior high, in the ninth grade, I was active in drama. I also sang in the Glee Club, until my voice changed. I had a part-time job, starting at about fifteen or sixteen. I worked a couple afternoons a week and on Saturdays. I think as I went through high school, I became progressively more active. I made honor society and student body president.

One of the good things about our high school was that students who graduated from the school tended to come back the day before holidays and during vacation periods. I think they sort of came back to say hello, but they also came back and told us stories about college. We got a kind of informal college recruitment and orientation from these students who were one or two years ahead of us. I knew about a number of places. I hadn’t been to any of them, but I knew about them. College recruiters started coming. I recall college recruiters from Harvard coming, and I was most unimpressed. I think it was a professor of English, and I think he must have been passing through. I don’t know how he’d be passing through Wilmington, but I do recall his coming and describing Harvard. We had older brothers of classmates who had gone to Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania, as well as to some smaller schools like Providence College, for example, and Brown.

I started looking at catalogues, and I was very struck by Macalester College in Minnesota. Their catalogue was very impressive. I really liked that catalogue. But I think as I got closer to it being a reality, I was much more influenced by what I thought was the campus to be at for the civil rights movement. This is 1963 that I’m talking about. The choice really came down to the University in Chapel Hill or Howard. A friend of mine had an older brother who was at Chapel Hill. I recall going there one weekend and the theme broke out a couple times. When I came back, I said, “This is where I’m going to go.” I decided to go to Chapel Hill and I was there through my undergraduate years.

What are a few of the significant things that you think about as far as being an undergraduate student at a predominantly white institution like the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, during the years that you were there? What things do you recall as significant relative to your education?

Well, actually, I had this very good school and I had a good education, but I don’t remember much about the classroom stuff. It was just an exciting time to be in college. I recall spending an awful lot of time participating in what was going on.These activities included continuing efforts in the civil rights movement. I was active in the Chapel Hill chapter of the NAACP. I became active in recruitment. I started a program called Carolina Talent Search. The university wasn’t in the mood to recruit black students. There were nine or ten of us in the freshman class.

How large was the class?

Twenty-four hundred.

And there were ten of you?

We were the first double-digit class of black students. In the previous year, there had been one or two or three. There was one student in law school, one student in the medical school. So ours was the first double-digit class. The classes became progressively more colorful as the years went on, but I think when I left, there were still fewer than a hundred out of thirteen thousand.

So I was active in that. I was active in sort of national policy issues. We had a group called the Carolina Political Union. It was a very old group. Chapel Hill was an old university, so they measured things in decades or even hundreds of years. The Carolina Political Union was a small group that met with distinguished visitors, dealing with policy and publications. I recall sitting in those meetings with the likes of the head of the John Birch Society, Hubert Humphrey, Ted Kennedy, and Mike Mansfield, who was Senate majority leader at the time. These would be people who, in addition to their public speech, would then sit down with a group of students. We were the group of students. I recall many of those meetings. We would meet twice a month.

We operated from the basement. I did a show once a week, basically played Nina Simone. I would play anything you wanted to hear, as long as it was Nina Simone.

I wrote for the campus newspaper briefly; I was a columnist for about a semester. I was a DJ on one of these sorts of electrical radio stations. It was a dormitory complex, and I’m not sure what these stations were called, but they didn’t go on the air, they ran through the electrical circuit. Everybody in the dorm could pick up this radio station. We operated from the basement. I did a show once a week, basically played Nina Simone. I would play anything you wanted to hear, as long as it was Nina Simone. It wasn’t one hundred percent Nina, but it was probably fifty percent now that I think about it.

I’m a big proponent of hers, too.

I was involved in a number of these activities. I went to class and I was a reasonably good student, but it was always clear to me that college was much too important to spend all your time in class.

That was a very exciting time to be in school.

That’s when I started carrying a calendar book in my pocket. It wasn’t to keep up with my classes — I knew when they were. It was all these other things that I wanted to be involved in.

That was like the mid-’60s?

We’re talking ’64 to ’68. I graduated college in 1968.

That was a very pivotal period during the civil rights movement, really. Could you talk a little bit about that time?

Let me just say a little bit more about being a student. I don’t want anybody to have the impression that I was one of these people who ran from event to event and never went to class. I had a number of very good faculty members. In fact, the way the first two years were arranged the whole second floor of the administration building was basically advising. They would have two dozen professors who would sit up there during office hours, and they would do advising. From the very beginning, I had a very good advisor. I never took a course from him, even though he was in my major. He basically talked and listened and was very supportive, which at that time was something I didn’t expect. I expected that we’d have to wrestle with these guys — either around the issue of race, because there clearly were people who weren’t exactly happy to see any black students show up, or with those who were tripping over each other trying to recruit new ones. But he wasn’t political in a sense. I think he was just a very good advisor, sort of helped me figure out this thing called the curriculum and so forth.

Then when I became a major in sociology, I had another good advisor who I did take classes from and who became my honors advisor. I worked with what is very similar to UROP. There it was only for honors students. To do honors, you had to do a project under faculty supervision. We had an NSF grant, which meant you worked over two summers and worked with a group of students in the department. He was my advisor, he was my thesis advisor, and I took a couple of his classes. So it was a very good thing.

One of the things I had hated about high school was physics. So I said to myself that I would never go to a college that required you to take physics.

I took some other courses that had nothing to do with my major. I took sub-Saharan politics, for example, because that was the period when Africa was breaking free. This was a way to get some history and current events at the same time. One of the things I had hated about high school was physics. So I said to myself that I would never go to a college that required you to take physics. I took zoology, which is fine. The only problem was that it was one of those courses designed to weed out people who wanted to be doctors from people who could possibly be a doctor. It was an overall good education.

You spoke of role models, and you mentioned some. Are there any other people you can think of who had an influence on you at that point?

No, there were no role models that I can think of. There were upperclassmen whom I admired. One is Mel Watt, who’s now the congressman from the Charlotte area. Mel Watt was a year ahead of me. He was one of those guys who were dead serious. I mean, every other hall they could be throwing water, screaming, playing loud music, but from 7 to 11, you didn’t make any noise on his end of the hall. He was dead serious. Then there was another guy who is now a cardiologist, who was also a year ahead of me. He was the same kind of guy, but he was deceptive. I mean, he would play basketball all afternoon and he would sweat as much as the next guy. Everybody else would go to sleep about 10 o’clock, and he would go to the library and stay there until it closed. Everybody would say, “I’m going away for the weekend,” and Charlie would say, “I’m going away too.” He went home to study organic chemistry, while everybody else was at a party. They couldn’t understand how he would get all A’s, while they would be struggling with a B and maybe not even that.

I wouldn’t say that they were role models, except in the sense that you could be serious and have fun, and be a good student. They both were very active in some of these same activities that I was active in. But when it came time to study, they disappeared and studied. Others, they played. I opted to follow the guys who studied.

After your undergraduate schooling, how did you get to MIT?

I had to decide, “What am I going to do with this education?” I ruled out all of the traditional professions. I actually think I came to college wanting to be a lawyer, but the more I saw of the legal curriculum, the less I thought I’d be interested in it. So I didn’t go to law school. I didn’t want to go to social work, or any of the other old professions. I don’t know how I got turned on to city planning, but I took a couple of courses in it, and it seemed to be the right way to go. I sort of minored in city planning.

When it came time to go to graduate school, I went to professors there and said, “What are the best schools in city planning?” They said MIT, Harvard, Berkeley, North Carolina, Penn. I ruled out Berkeley, because I really didn’t want to go to California. Penn didn’t strike me. So I applied to North Carolina, Harvard, and MIT. I came up to visit. I visited Harvard, visited MIT, and let them know that I would go to MIT if I were admitted. The rest is history.

When you think back, talk a little bit about your experience at the Institute. You have a student aspect as well as a professional aspect. As a black student coming into the graduate program, what are some significant things you could point out about that experience? Then talk a little bit about your experience so far as a professor.

Well, we have to back up for a moment. You recall in 1966 that the war heated up very much. The issue from ’66 on was how you avoid the draft. During that time, the way you avoided the draft was to be a good student—that is, make two points, whatever it was, on a four-point system.

The next year, which would have been my first year of graduate school, I spent basically trying to jump through every tiny crack in the Selective Service law I could find. I was ultimately not successful.

That wasn’t an issue for me, but it became an issue the day after I graduated. I think I graduated May 30, or something like that, and I got a letter from my draft board on June 7. The next year, which would have been my first year of graduate school, I spent basically trying to jump through every tiny crack in the Selective Service law I could find. I was ultimately not successful. I was offered a number of ways out, which would have worked, but I didn’t take them. One was to go to Canada.

And you didn’t want to go there.

I said, “If I go to Canada, I’ll have to stay there for the indefinite future.” You couldn’t even come home to visit, because the FBI would be waiting for you at the door. So I ruled out Canada. You could, if you were a father, get a fatherhood deferment — an exemption, actually. But I wasn’t a father. Here I was twenty-two years old. I didn’t have a steady girlfriend, much less a kid, but somebody did offer marriage and adoption. All of this year, I was trying to find a loophole. I could have said “I do” and signed up as a father, but I said, “No, I don’t think I want to do that either.” I could have gotten out as a teacher, but here I was as a student. We tried that route. I recall getting two or three deans to sign something and try to force that off on the draft board. They didn’t buy that. I tried medical, but there wasn’t anything wrong with me. I had fallen and hurt my back a couple of years before, and some doctor found some little minor abnormality in the twenty-third vertebra or something, but the draft board wasn’t impressed by that.

Ultimately, I was drafted at the end of the first year. A lot of that first year, my extracurricular activity was reading the Selective Service law and figuring out what I could do to avoid the service. I found the first year to be a good year academically, but I certainly was distracted. I had gone through a period of being a black student at a white university, so MIT was nothing compared to Chapel Hill. People were saying that there were white folks who were against you. I said, “Of course there are, what’s new?” There had been incidents at Chapel Hill. There weren’t any violent incidents, but there were a number of events that occurred three or four times a year that reminded you. Dr. King was killed the spring of my senior year, and that produced a bitter period. We had some fraternity pranks.

Dr. King was killed the spring of my senior year, and that produced a bitter period.

We had campus elections. Student government was serious business in Chapel Hill. There were some people who were extremely serious about it. Students disciplined each other, and so participating in student politics was real business. This stuff here at MIT in The Tech is not newspaper-worthy. I was in Texas yesterday and read the Texas Daily — or the Daily Texan — and that reminded me of our student paper. It was a full paper that talked about the business of being a student, students participating in government, student factions. It was a real sort of community. Chapel Hill was a highly self-regulated community.

All of that was quite interesting. You had to be about taking care of business in those days at a place like Chapel Hill. The few of us there would get together from time to time and go in and see the chancellor. You didn’t call them “demands” in those days; we just sort of suggested that they ought to look for some black students to join us. We were sort of lonely. The chancellor was a nice old gentleman. He would listen to us and say, “Thank you very much for coming by.” We had a dean who was more contentious. As I think back on it, one of our strategies was basically to stir him up, because every time we stirred him up he said something stupid. That was the best kind of campaign that we could get going within the administration — stir up the dean to say something stupid, everybody would be embarrassed, it would be in the newspaper, and we would say, “See?”

Was this the dean of students?

The dean of student affairs. Then there was a dean of men and a dean of women. I recall that in one meeting we were talking about fraternity discrimination. None of the fraternities would accept us. We may as well not even bother to go to rush. We went to complain about that. I don’t think I would have joined even if they had said, “Come on in,” but I just wanted to make the point that it should be my choice, not theirs. We went to see the dean about that, and he said, “You know, I understand what you mean, but you have to understand discrimination. I was a Methodist at a Baptist college. The Baptists said the Methodists were going to hell, and I could have let that upset me, but I didn’t.” And we looked at each other, “Why is he talking about Methodists and Baptists?”

I also remember that in a way we were obliged to look out for each other. I recall some of my brothers who weren’t all that conscientious. I’d go to them, get them out of bed and say, “You have an exam tomorrow. You can’t be in bed at 8 o’clock, so get up.” I’m sure students do that for each other now, but then it was survival. Like the dean said, one out of every three of us is going to flunk out of here, so let it be some of those guys, not us. We can’t afford to lose anybody.

Like the dean said, one out of every three of us is going to flunk out of here, so let it be some of those guys, not us. We can’t afford to lose anybody.

Tell me a little bit about your move into the MIT arena. Talk a little about the significant events that have happened to you. I think you were clearly one of the first blacks to get a Ph.D. here in your department, and also certainly the first to move into the faculty ranks. Talk a little bit about the black experience in that regard.

There was very strong faculty support from the very beginning. The faculty who were there, and who were around most of my time at MIT up to now, were Bernie Frieden, Langley Keyes, Lloyd Rodwin. Ralph Gakenheimer had been an assistant professor at Chapel Hill. I took a course under him. When I left Chapel Hill, he left and came here, and I came here. So there were those four plus three others who were well outside of my field. Lisa Peattie, Aaron Fleisher, and Kevin Lynch were the main faculty. All of those people, especially Langley and Bernie and Lloyd, were always very supportive from day one. They never said, during my first year or second year or whatever, “We’re grooming you for a faculty position,” but they were supportive in several things that I can remember in particular. Bernie was my advisor, from the first day through the Ph.D., and he always gave me suggestions about how to take the next step. He always asked in advance about how I was dealing with choice, about making sure I knew about choices and offering to advise me on making those choices. On a number of occasions he provided support, both in ways that I know and in ways I’ll probably never know. Later I would get support as a junior faculty. Someone would call me up and I’d say, “How do they know me?” Because somebody had to tell them! I’m not even sure my name was in the catalogue at that point.

And that has happened throughout. While Bernie was never department head, he was head of the Joint Center for Urban Studies and was certainly supportive in that regard. I had a Joint Center fellowship, I had an RA at the Joint Center. When Lloyd and Langley were department heads, they made sure that I wasn’t without resources — not the kind of resources you have to leave MIT to get, but the kind of resources that are within MIT. So I was an RA, a TA, and I had a Joint Summer Fellowship when I reached the dissertation stage. And then when it came time to consider faculty positions, they made it clear that I was welcome to consider it, that they would welcome my interest. They understood that I might actually look elsewhere. I did briefly, but not seriously. When I indicated that I would be willing, they advised me on the steps that I had to go through.

At some point, I don’t remember exactly when, the die was cast. I finished my dissertation in February ’75, and I would go downstairs to the Personnel Office and join the faculty. It was quite ordinary. Lots of people in the department did that. It wasn’t as though this was anything special. This was the same time that Larry Susskind was joining the faculty. I think Larry was Class of ’73 or ’74. Larry Bacow was the same year, I think, although he was not at MIT. He was down the street at Harvard. They both joined the same year. I may have been spring. I may have been February and he was July, but I think we both have 1975 as our starting date. And there were a couple of other people I can’t remember. That continued through promotion, the Joint Center position, the advice on sabbatical.

What continued?

The support, from these same people. And then there were other people who joined the faculty who also supported me. In fact, I can’t think of anybody who was outright negative. Now they may have been negative behind my back, but they certainly weren’t negative in the sense of throwing out roadblocks or tricking me or giving me bad advice or leading me off on tangents.

What do you like best about your experience at MIT so far, and what do you like the least?

Compared to other places I know, MIT is unpretentious. I liked that from the very beginning, from the time I came here to interview. People talk to you. They didn’t sort of indulge you or wonder why you were here. When you told them why you were here, they said, “Okay.” They may not like it, they may not agree with it, but they say “Okay, that’s why you’re here.” I think the impression that other places give is that faculty is some kind of an aristocratic calling, that you’re sort of born into an academic life, that you don’t achieve it, or that you can’t earn it. It’s sort of like a calling. The decision is which field you’re in, what’s your style, and that sort of thing, whereas I have very much the sense that MIT is an engineering place. These are people who like to solve problems. While I may not like all the problems they try to solve, or all of their solutions, there is a common strain through most faculty like that, and I find that comfortable. As long as you don’t assume that people are going to agree with you, and as long as they stay out of your way, then I would be comfortable.

You’re very unusual as a black professor here, as you know.

Maybe those other guys aren’t usual.

Let me tell you why I say that. First of all, you are a first in several categories. If I start with one that sticks out in my mind more than anything else, it’s that you are the first black to be the head of an academic department here at this institution. When you look at that, I think it’s important that you say something about that for students and young, black faculty members coming in. I mean, how do you do that?

Basically, to be a department head here you first have to be more or less trusted by a broad cross-section of your department. While department heads have considerable power, they don’t have absolute power. They have to sort of knowhow to read people, how to figure out how to get the most out of the situation that they can, and to motivate other people to be collegial. I think I have the reputation for being able to do that. I never tended to pick favorites, or establish a position and refuse to talk about it, or operate deceptively, or have my personal agenda so tied into what I do that you can’t tell me from what I’m doing for the department. I’ve always tended to segregate my personal agenda from my faculty agenda. That’s always been comfortable because as long as they are separated, then I can do in each one what I want to do and not have to worry about how it’s going to appear in the other segment.

Not all faculty members are willing to do that. There are some faculty members who are good colleagues, but when they say something, you have to sit down and say, “From under which hat does that come? Is that Professor X, the teacher, Professor X, the administrator, Professor X, the consultant, Professor X, the friend of these people over here, Professor X, the advocate of –ism?” You don’t know which hat it’s coming from under. I don’t think I present myself that way, and therefore I’m more likely to be trusted. Now that doesn’t mean people agree with me. When I was department head, I would regularly get letters telling me what a terrible job I’m doing and how the department is going to hell in a hand-basket, and that I was leading them there, and the only redemption was such and such. And I said, “Oh yeah, this is about time. It’s been thirteen days since I had one of these letters from this person.” So I just put it down, and in a week I send them a note saying, “Thank you very much for your suggestions. I liked point no. 1.” End of memo.

You also have moved into a really new position, again I believe a first, as associate provost. In my memory, I don’t recall any black being associate provost here. Again, although it’s still early, how would you describe your experience so far in that kind of role? You’ve seen it from several angles now.

Actually, it’s a continuation, although it’s different in the sense that you’re not frontline. In the department, you have the budget. Somebody can suggest something and you can say, “No, no way.” As associate provost, you can’t do that, because you basically operate at the instruction of the provost. I want to say no, but I feel I have to say no on Joel Moses’ authority, or Chuck Vest’s authority. Or I have to say, “We’ll look into it.” That is, the answer is no, but I’m not going to tell you no right now. I’m going to just go back and double-check, and then I’ll have them tell you no, or I’ll come back and tell you no, having cleared it. That’s different, and that requires you to slow down a bit. But most of the job isn’t about saying no, the job is about getting people to say yes. Which is actually what a department head does too, except you have both the carrot and the stick.

Now, there is a part of the job where people who don’t know me have to figure out, well, who is this guy? My style generally is not to give them an emotional resumé. You watch, and then you’ll see. But I’m not going to threaten or promise or tell you everything about me in a way that allows you to figure it out, because I don’t know whether you’re somebody who wants to understand or you are just trying to figure out how to frustrate what I’m doing.

I wonder where you learned all this stuff.

I sort of take it as it comes.

You’ve indicated particularly where a lot of your mentors and role models and supporters came from. Is there anything else you can say about the sort of support you have received from senior people here at the Institute?

Again, I can’t think of anybody who to my knowledge has put up a roadblock. I can also think of people whom I’ve gone to for advice. Over the years, there were people who were outside of that mentoring, outside of the sort of informal mentoring group in the department — people like Frank Jones and Willard Johnson and you, and others to whom I’ve gone and talked about things while they were on my mind, or when I’ve made up my mind, or while I’m thinking or trying to make a choice. I think that’s been useful for a couple reasons. One, I’ve gotten valuable information. And most people have been willing to share, that is to tell me, “Gee, it’s a bad idea, and if you decide to do it anyway, here are the things that you should watch out for.” Or, “It’s a terrible idea, but if you do it this way, then that might make it a little more palatable or acceptable or beneficial or whatever.”

That’s always been good, and I very much value seeking advice. That’s actually a style that works well for an administrator, because sometimes in asking for advice you’re basically asking people to join you. They’re a little less adversarial about things. It has two benefits — it helps me gauge and it sort of gets a generally positive reaction.

When you think about your experience here, what kind of advice would you give a young Phil Clay coming into the area you’ve experienced here?

One, build your network on the outside. Ultimately, you get ahead at MIT because of people outside of MIT. The other piece of advice is to get to know people inside of MIT. This was a piece of advice I got a long time ago. Because I’m naturally shy, those were periods when I did things that I really didn’t want to do, that I didn’t feel particularly comfortable doing. But from every source that I got information, I realized I had to do it. I would call people and invite myself to meetings.

Build your network on the outside. Ultimately, you get ahead at MIT because of people outside of MIT.

I remember the first book I wrote, I heard there was going to be a working meeting at a foundation in Washington to talk about this subject. Of course, I hadn’t been invited. But somebody with whom I was corresponding had been invited, so I got enough information from them about where it was and who was arranging and so forth. I remember calling the person up and inviting myself to the meeting, saying I was going to be in Washington and I was working on this project that had funding from the National Endowment of the Arts or whatever it was, and would very much appreciate the opportunity to share some of my work with other people at the meeting such as So-and-So, and So-and-So, and So-and-So — none of whom I knew, but I’d heard they were going to be at the meeting. I’m sure the person said, “Oh, this sounds like somebody we ought to have, even though I don’t know who the guy is.” So I got an invitation, I showed up, and there were two or three people there who became people who would read my work and knew what I was doing and so forth. I felt very uncomfortable doing it. I’m sure I was wet with sweat when I got off the phone. But I had a great sense of accomplishment to get myself an invitation to a key meeting.

There are a couple of situations on campus that weren’t quite like that because it wasn’t as urgent. This was a one-day, one-time meeting. At MIT I probably waited six months longer, but you have to do it. I recall one minority faculty member who did not get tenure and who had been advised many times to do just that. There was a faculty seminar both at Harvard and MIT on his research, and he was told, “You’ve got to go.”The entree was made. He wasn’t grabbed by the hand and led into the seminar, and had his name put on the schedule, but everything short of that. He never did it because I don’t think he felt comfortable. Of course, those seminars weren’t going to reach out and say, “Ooh, who’s out there that we don’t know about? They should come to our seminar.” I remember when the case was discussed, the question was, “He won’t make it because he hasn’t connected with the people who he would have to, to get through MIT, to say nothing about the outside.”

That’s excellent advice. On the flip side, what would you suggest to the Institute in terms of improving the experience of blacks coming to MIT?

Well, it’s tricky because we can in retrospect say what ought to happen, and we can assign somebody to do it. For example, we could say, “Clarence, you’re assigned to work with So-and- So. You should call XYZ seminar up and make sure he gets on the program for next spring.” And you can tell the guy next spring, “We want you to present at that seminar.” Now, for both you and that person, that’s unusual. That might be viewed as, “Gee, I don’t know whether this guy’s any good. I don’t want to stake my reputation dragging him over there.” Or that guy would say, “Well, I’m not ready. I don’t want to embarrass myself by going to that seminar presenting.” And if anything happens, then everybody feels like, “Gee, we caused it.” Or if it happens, and some of these seminars can blow you away — it could be a job seminar or a regular seminar — “Gee, that’s the worst paper I’ve ever heard! That’s a stupid idea!”

And you can blow somebody away. So nobody wants to take the risk of either introducing a new person into that situation, or a new person saying, “I’m ready to go,” and then being chewed alive.

What you’re saying is that basically a lot of it has to happen through intuition of the person getting advice as to what you ought to do, and then sitting back and seeing whether that person would do it or not.

That is, each person has to make a baby step toward an ideal relationship — not a big step. For example, maybe this person can’t go to the economics seminar and make a presentation because he isn’t ready. Maybe he ought to have a presentation within this department. Or maybe he will present it at a professional conference where there’s a mix of academics and professionals and the standards aren’t quite as high. Give him some experience making a presentation. Let him be criticized by some people who don’t matter as much at this point.

So there are any number of questions, but the issue is that there’s a risk-taking which you’re asking people to do, and there’s a chance that if you ask them to take a risk and they blow it, they blame you. They say they weren’t ready because they weren’t warned that Professor X likes to chop up assistant professors and spit them out. We know they’re out there. You never know when they’re going to show up. And sometimes it’s a graduate student.

You can be the best XYZ there is, but if you aren’t connected to this person or that person, if you don’t help build a program in a lab and a research program, the question is going to be — Well, what contribution did he make?

I remember going through hiring a couple of years ago. I think at one point the Ph.D. student said, “Let’s see who we can go chew up today.” They would come in and the faculty would ask these softball questions. Then a graduate student would raise his or her hand and ask a very good question, but it was clear that that’s the kind of question that stretches this person, makes them embarrassed. They didn’t come prepared for that question, and it was clear. Of course, the graduate students sit back and sort of look smug.

Finally, over the twenty years that we have been here, we have not had much progress in terms of increasing the black presence, say, in any large dimension on the faculty. What do you think of your experience in what you’ve seen? What do you think are the issues there and what kinds of things would you suggest that we as an institution can utilize?

The decisions about who joins the faculty are typically made by a small group within the department. Departments will form a search committee, and it’s in that committee that they basically shape the job and select the person to fill it. In those cases where there are potential candidates, increasingly we have the situation where the job is so narrowly defined that it’s hard even if you find someone who generally meets the requirements. Put another way, if the biology department goes out to look for, say, a neurobiologist as opposed to a biologist, some- times in the past we would say, “We have found a very good biologist, we’ll hire him.” But then they come and they don’t fit the expectations for who is to be hired at that time. I could think of a number of cases where people have come and they’ve been very good, except they weren’t very good from the point of view of some narrow interest within the department, either at that time or subsequently. I can also think of cases where people have sort of unfairly been denied the opportunity to be the best they could because whatever they can do wasn’t valued at that time.

That’s a very steep mountain climb. I think, as we cut the faculty, there will be more and more positions like this.There was a time when we went out and hired, when we were looking for the best person available, with combinations of things listing several fields. So we went out and looked for someone in housing, environment, or transportation. Now we’re likely to go out looking for someone interested in environmental policy in developing countries, which means you have a double filter. You’ve got to have an environmental background and you want to or have experience in applying it to developing countries. I think the hill is actually getting steeper, and the question is — is there a way to turn that around in the environment we’re coming into now?

So you’re saying that it’s becoming more specialized.

Yes.

Which makes it more difficult to get blacks who could fit into these pigeonholes.

Yes. It used to be that you could go into a meeting and someone would say, “Well, there’s a black student graduating from UCLA in such-and- such,” and the only question was — is such-and- such a reasonable field at MIT? If the answer was yes, then you would pursue the person. Now, the question is — “Well, we’re looking for someone in X, and this person’s in Y. We can’t really consider them. Even if we do, then we wind up in some cases doing them a disservice because we bring them here and nobody’s interested in that.” And sometimes the leader of the opposition is the faculty in the area who would hope to get somebody in that slot.

So the person has a very slim chance of being able to make it, even if you brought the person here.

Well, okay. There’s a solution to it, and one is that you do a bit more forward hiring in departments where you know there are going to be retirements or vacancies. Then you can hire not because you need the person now, but you think you’ll need them in five years. And you tolerate a bit of duplication. Give the person a smaller teaching load, more research time during that period. Have them co-teach to sort of get up to speed in the area. We’ll have to do inventive things like that.

Is there anything that you think you’d like to talk about, over this long period of experience you’ve had here, that we haven’t gone through?

I think that it would be a bad idea for someone to come into a faculty position without full knowledge of the circumstances here. More than most places, this is an entrepreneurial, interdisciplinary place. You can be the best XYZ there is, but if you aren’t connected to this person or that person, if you don’t help build a program in a lab and a research program, the question is going to be — Well, what contribution did he make? You may be very good, but what have you done for the program, the department, whatever? By building those relationships inside and outside of MIT, you get a chance. Even if you don’t get tenure at MIT, you’ll get tenure somewhere else, and be just fine.

Because of connections.

That’s right.