Flow Alone Won’t Make You a Writer

My favorite quotation about writing comes from Thomas Mann:

A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.

That’s counterintuitive. If you’re a professional writer, then writing should be easier for you, right? But creativity research shows that successful creativity is effortful. Flow is enjoyable but it’s not enough.

You probably write more than you realize. A Microsoft study found that the average worker receives 117 emails a day and 153 chats a day. If you add up all of your typing at the end of the day, you’d be surprised at how many words you’re writing on a regular basis. This writing is goal-driven. You ask someone for information; you apply for a job; you update your LinkedIn profile; you collaborate on a project team. It’s part of your job.

But I want to talk about writing without a purpose, writing that you don’t do for your paycheck. This includes poetry, short stories, or fan fiction. Maybe you keep a daily journal. This writing doesn’t have a goal; you do it for its own sake. Psychologists call this intrinsic motivation, and it often leads to what my doctoral advisor Mike Csikszentmihalyi called the flow state.

In flow, you realize your fullest creative potential. You lose track of time. You’re not distracted by little things around you. Flow is like a drug. Once you’ve experienced it, you want it again. This is why people write without a clear purpose: to experience flow. It’s a stark contrast to writing for a job, where the motivation comes from external rewards — what psychologists call extrinsic motivation.

The flow state is a challenge to behaviorism, because you keep doing a task without any visible reward.

Intrinsic motivation poses a challenge to behaviorist theory. Csikszentmihalyi and other flow theorists were humanists, not behaviorists. In behaviorist theory, human action is an iterative cycle with three steps: take an action, receive either positive or negative feedback to that action, and modify your behavior to increase the likelihood of future rewards. It’s a theory built on extrinsic motivation. The flow state is a challenge to behaviorism, because you keep doing a task without any visible reward. The task is so satisfying that you might do it even when it might not be to your material advantage. This is why people choose to be starving artists rather than relatively successful middle managers. It’s why I left my high-paying job in New York international banking to become a poor doctoral student. I’ve never regretted it, and I’m often in flow when I write.

But in fact, flow often leads to success (however you define it). Paradoxically, when you stop responding to external rewards, you sometimes become more successful. Research shows that acting from intrinsic motivation often leads to greater success, especially if creativity is your goal. The most famous creatives describe being in the flow state as they work. Rigorous scientific studies show that new breakthrough ideas tend to emerge from a flow state. That’s especially true with problem–finding creativity, when you discover a new problem to solve, or you approach an existing problem in a surprising new way.

I’m a creativity researcher and a flow theorist. So you might be surprised to hear me say that flow isn’t enough.

People love the concept of flow because everyone wants to be told, “do what you love and the money will follow.” Mike’s 1990 book sold over a million copies. Flow is a variant of “trust yourself” and “defy the crowd” and “pursue your own dream.” And, yes, it’s true that the flow state often leads to greater success. But flow isn’t enough. The most successful creative people combine flow with hard work.

I’ve published 20 books, each the result of intense dedication and hard work. But I also experienced a lot of flow. I often lost track of time and became completely absorbed, sometimes to my wife’s dismay. But for me, periods of flow are interspersed with equally long periods of revising, editing, and fact-checking. Everybody loves the flow stage of writing but most people don’t like the hard work stage. That’s Thomas Mann’s point: To be a successful writer, you have to work hard. Creativity research has shown that the most successful creatives love the tiny tasks that others find tedious.

I was inspired to write this essay after reading Klara Feenstra’s recent New York Times article, “Writing a Novel.” Feenstra starts her essay by describing the flow state as a form of escapism:

When I first started writing my silly little novel, it was a desperate attempt to escape the demands of “real life.” I wrote and wrote, falling into a delirious state, the I.V. drip of my imagination funneling uninhibited into what I was sure was the next “Middlemarch.”

This is why many people start to write. But she soon realized that flow wasn’t enough:

I had an impulse to set the book in Zalipie, Poland, but I knew nothing about Zalipe. I wanted my protagonist to have a lucrative career and had heard “underwriting” was a solid profession. But what was an underwriter and how do you become one? While we’re at it, what’s the plot of this novel? Suddenly there were all these tasks to be completed, so many that I had to start a spreadsheet to keep track.

A spreadsheet? That doesn’t sound like flow at all. Is updating a spreadsheet “writing”? Or does this hard work prevent her from writing? Feenstra realized that, in fact, this is writing. It’s why Thomas Mann said that writing is harder for writers. I love what Feenstra says next:

I didn’t so much “flex my creative muscles” as slog through an unpaid internship to myself.

Writing a novel isn’t quick. It’s not easy. Feenstra took years to generate the first draft, and then she realized she was only on the first step of a tall ladder:

Several manic years passed like this: I wrote, rewrote, researched, revised, took workshops, added characters, deleted them. And finally, one day, I had a book.

But soon she realized that she still didn’t have a finished novel. That is, it had not reached its full potential; it was not fully realized. It wasn’t ready to be released into the world. There was still plenty of work ahead — surprises, emergence, more spreadsheets. Creativity research shows that this is always the case. A truly successful creative process is wandering, exploratory, and iterative. I call it the zig zag path. The best creative works emerge from the process; they don’t jump out of your subconscious onto the page. Yes, you need to put stuff on the page to get the process started. But, after that, creativity becomes a dialogue between you and the evolving work.

A truly successful creative process is wandering, exploratory, and iterative.

When Feenstra was finally done, she realized:

The novel I ended up with is nothing like the one I started.

But this hard work wasn’t all toil and misery. Feenstra gets in the flow state even while she’s doing the revising, editing, and all of the other “not inspirational / not subconscious” stuff. This happens to me, too. It’s not the same kind of flow as when the words just come out of the I.V. to your soul, but I find it intrinsically motivating. Feenstra discovered that

Being in the flow state of writing had always given me a druglike joy, but reworking a novel over and over, feeling sweaty and frustrated and stuck and then getting unstuck — this kind of grown-up work was thrilling. So I’ve come to honor the procedural graft of it all.

Flow isn’t enough. Creativity can be a form of meditation, and that’s wonderful and affirming. Flow is a great reason to write. But what separates the successful writers is that they know how to enlist flow in a longer, wandering process of creating. As Feenstra writes, “Writing my book delivered me the unglamorous yet oddly comforting realization that work is work; that there is no magic trick out of reality.”

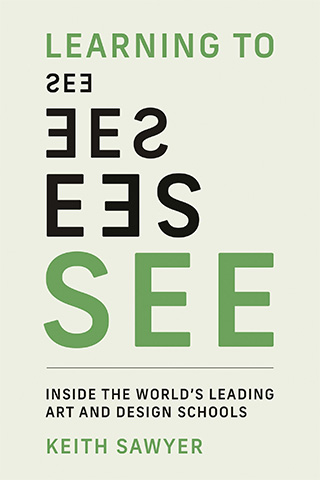

Keith Sawyer is one of the world’s leading creativity researchers. He has published 20 books, including “Group Genius,” “Zig Zag,” and, most recently, “Learning to See.” Sawyer is the Morgan Distinguished Professor in Educational Innovations at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A version of this article first appeared on Sawyer’s Substack, The Science of Creativity.