Sky Gazing on Mars

You close your eyes and imagine that you are walking along a flat, dusty plain. All is silent in this place except for the crunching beneath your feet with each step. As you proceed, you sink in just a little as you break through a white crust just below the surface. Purely by accident, you strike a small rock, left undisturbed for eons.

Oops.

Startled at disturbing the quiet, you open your eyes to see the rock flying away, traveling farther, and hanging in the air longer than your earthly senses tell you is reasonable. But with just a third of Earth’s gravity in this place, the logical part of your brain reassures you that this is completely normal.

So, you resume walking, continuing onward, looking for that perfect spot. Somewhere you can lie back and just stare up at the sky for a few minutes. Somewhere you can contemplate this place and the clouds scudding along overhead.

Though it might not seem like it at first, Mars has the most similar surface environment to that of the Earth of nearly any place in our solar system. An exceptionally dry, exceptionally cold environment, to be sure, but something we can recognize on human terms, even if it isn’t a place where we could survive without the protection of a space suit.

Here, overnight snow is not unheard of, although the environmental temperature and pressure range cannot create the liquid water clouds necessary for rainfall. Ice fogs fill many low-lying areas before burning off just after dawn. Sunrise itself is dramatic: a disk one third smaller (but no less bright) than what we are used to at home throws the dusty landscape into stark relief.

Sunrise is dramatic: a disk one-third smaller (but no less bright) than what we are used to at home throws the dusty landscape into stark relief.

You see your spot: a sandy dune that has drifted up against a bench of rock. Over time, the thin winds of this place have pushed and piled the sand up against this obstruction. Sitting down, you settle into a comfortable position and tip your head backward.

Cloud Gazing

Most of the time, what clouds there are on Mars are very faint. But not today. It is aphelion season, when Mars is as far from the warmth of the Sun as it can get in its circuit around our star. With that cold comes a band of clouds made of water ice — cirrus clouds — that stretches around the planet at the equator. Vivid streaks of wispy, painterly shapes cascade across the sky, resembling the tails of horses.

The clouds move horizontally with the winds and seem to fall like icy waterfalls in extreme slow motion. An immense number of cloud particles, born at high altitudes, fall into drier air below. As they approach the surface, they evaporate, becoming smaller and falling slower until they disappear completely; this precipitation is called virga.

But these are not the only forms you see in the sky. From past walks you know that sometimes there are rows of clouds that appear to stretch from horizon to horizon, all traveling together like parallel streets on a map. Sometimes even more complex patterns form. It’s not unusual to see two separate sheets of clouds at different heights moving at different speeds and in different directions. Other times, the patterns interfere, creating a grid-like texture. One of the strangest forms consists of a cloud that seems to appear out of nowhere, then climbs over an invisible hill and disappears as it falls back to the level from which it began. It’s just one more reminder that invisible atmospheric humidity and bright-white cloud particles are just two sides of the same watery coin. When the conditions are right, each can transmute into the other and back again.

The Colors of the Martian Sky

Turning to look toward the Sun, you see a broad and milky brightness on the same side of the sky. Uncountable numbers of dust particles scatter the sun’s light toward you, as if the whole sky was made up of glare from a dusty windshield. That scattering is most efficient in the red, lending the sky a salmon-orange color. On Earth, we see a bright blue sky during the day, and, at sunset, the Sun turns a deep red color along with the sky in the direction the Sun is setting. Mars experiences a mirror version of this.

Why? Dust can scatter all different colors, depending on the size of the dust grains and the amount suspended in the atmosphere. On Mars, the dust particles happen to be a bit bigger than the wavelengths of visible light, and so they tend to scatter a reddish hue. If you couple this red scattering by dust with the fact that the actual amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is small (and therefore doesn’t create a lot of blue light to begin with), the dust-scattered light dominates, and you end up with a pale salmon color during the day.

You glance at the time and realize that you’ve been lying here sky-gazing for hours. It’s time to start moving again. With some reluctance, you fold yourself up and rise to a standing position. But instead of heading directly back the way you came, you decide to loop by an old historical site on your way.

It’s a bit of a climb to where the Curiosity rover came to rest, high in the foothills of Mount Sharp. As you head up the trail, you cover in an hour parts of a course it took this spacecraft years to drive. Here and there you can see the imprints of the wheels. At some point, this will all be roped off and controlled, like any historic site. But for now, you are one of only a few people on Mars, and none would dream of disturbing the soil.

Following those tracks at a safe distance, you eventually come across the spacecraft itself. You circle around the front to get a better look and glance up at the cameras on top of the mast, above your head. The Sun is sinking lower and lower on the horizon. Time to get back home.

Phobos rises in the West, a bright and noticeably potato-shaped moon that starts streaking across the sky to set in the East.

As you travel, the Sun becomes less and less bright. The light rays, passing more steeply through the atmosphere, must run the gauntlet of greater and greater quantities of dust. Often, when this happens on Earth, the disk of the Sun itself becomes a deep red color. But here, with the dust scattering away all the red light to other parts of the sky, the Sun becomes a brilliant blue-white jewel and the sky near the Sun changes color to match.

Just as you reach the habitat, you catch the last rays of the Sun over the crater rim. Phobos rises in the West, a bright and noticeably potato-shaped moon that starts streaking across the sky to set in the East. Just one more example of something hauntingly familiar in this environment, yet subtly different and exotic. As much as you want to stay outside and experience all that the Martian night can show you, you’re keen to get inside. You know that the same dust that caused the spectacular sunset will also make darkness fall much faster on this planet, and the forecast called for temperatures around 200 degrees below zero tonight. So, as the door opens, you slip into the airlock, looking forward to a warm meal with good friends, no less familiar a ritual for taking place here on the dusty plains of another world beneath a cloudy sky.

John Moores is the York Research Chair in Space Exploration at York University. He is an author of nearly 100 academic papers in planetary science and has been a member of the science and operations teams of several space missions, including the Curiosity Rover Mission.

Jesse Rogerson is Assistant Professor at York University. He has over 15 years working in some of Canada’s premier museums and science centres, including the Ontario Science Centre and the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

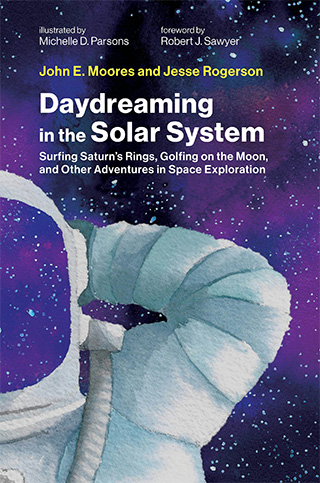

Moores and Rogerson are the authors of “Daydreaming in the Solar System,” from which this article is adapted.