The Surprising Impact of Recessions on Human Health

I first became interested in how changes in the economy impact human health while working on a seemingly unrelated topic — diesel exhaust and lung cancer in truck drivers. I started this research at Harvard as part of the appropriately named study TrIPS, or Trucking Industry Particle Study. At that time, the evidence linking air pollution with diseases like lung cancer was still considered by many to be inconclusive. It was not until 2012 that the International Agency for Research on Cancer definitively linked diesel exhaust with lung cancer by identifying it as a known human carcinogen.

As a postdoctoral research fellow, I was given the daunting task of developing a diesel exposure profile for thousands of truckers to match with lung cancer outcomes and determine whether diesel might have contributed to their deaths. While we had substantial amounts of data and detailed information on diesel exposure in the recent past, there was very little to go on for the vast majority of these truckers’ work histories, many of whom had decades of experience and exposure on the job. So I went searching for variables that might be related to air pollution to help reconstruct past trends on how much dirty air these workers might have been exposed to on the job. As a newly minted economist, I naturally turned to economic data, looking to employment trends in the trucking industry and economy-wide indicators of the business cycle for clues.

As the story goes, the upside of a down economy is that you have less money to do bad things.

I was surprised to learn when I first started digging that economics had a lot to say about the relationship between a bad economy and human health. The most recent cascade of studies began in 2000 when economist Christopher Ruhm published a paper examining the link between mortality, unemployment, and income across the United States. Using more advanced statistical methods than previous studies, Ruhm found strong evidence to support the counterintuitive idea that health actually improves during economic downturns in the form of lower death rates, with the notable exception of deaths by suicide. He argued at the time that reduced employment and income factor into our ability to consume “bads,” products like alcohol, cigarettes, and excess food. Also, physical activity might increase as people walk more to avoid the cost of gasoline and vehicle upkeep or eat less food (or eat out less often), decreasing obesity rates. As the story goes, the upside of a down economy is that you have less money to do bad things!

Although much of the subsequent research on economic downturns and population health from across the globe corroborated Ruhm’s original findings, other economists have reached the opposite conclusion. Study results vary based on how the data is aggregated (individual, county, state etc.). There are also conflicting results depending on the health outcomes observed, including various measures of chronic health and disability compared to the overall mortality rates observed by Ruhm. Some have suggested that the relationship between economic downturns and health has weakened over time and is no longer as relevant as it was in the past. Depending on the circumstances of the particular recession observed, which industries and workers were hurt most, safety net measures in place, and so on, there are ultimately winners and losers in the health outcomes game.

A growing literature around “deaths of despair,” which refer to deaths from drug and alcohol abuse as well as suicides, is drawing attention to the stark reversal of health fortunes among middle-aged non-Hispanic White populations in the United States. In one study, researchers estimate that half a million deaths between 1999 and 2013 among middle-aged White Americans could have been avoided had the mortality rate held constant at its 1998 level. A striking rise in drug overdoses, suicides, and chronic liver conditions related to drug and alcohol abuse represent the lion’s share of the mortality increases; however, this cohort’s lower life expectancy is not mirrored in any other U.S. demographic, age, or ethnicity. Put a bit differently, a White non-Hispanic American between the ages of 45 and 54 today can expect to live a shorter life than their parents.

The steady year-to-year increase in the mortality rate for this age group over more than two decades makes it difficult to attribute deaths of despair to any one specific recession, economic crisis, or labor market trend. Research highlights the potential roots of mortality in the opioid epidemic, accessibility of prescription painkillers, and addiction as well as the physical, mental, and emotional health fallout related to pain, substance abuse, and disability.

But an important clue linking these deaths back to the job market is the role of education as a risk factor: 90 percent of overdoses in the United States occur in people without a college degree. This group is also more likely to experience “serious mental distress” compared to their more educated peers. Further tying deaths of despair to the workplace, a recent report on Massachusetts workers identified physically demanding blue-collar work, low-paying work, high job insecurity, and lack of paid sick leave as risk factors in opioid deaths.

Ninety percent of overdoses in the United States occur in people without a college degree.

As the labor market continues its transition toward a technologically advanced and sophisticated service sector, those without a college degree are left with a shrinking share of the pie. Evidence from the sociology literature has related the increase in deaths of despair and particularly drug overdose deaths with de-unionization efforts at the state level. Inequality in work conditions has been referenced by some as a driving force behind growing health inequities nationwide. Interestingly, the precarity and economic insecurity associated with less-skilled work has been associated with increased physical pain, reduced pain tolerance, and a greater use of pain medication, all of which are important risk factors in opioid drug overdoses. And it turns out that it is not only one’s own job insecurity but also those of your colleagues and peers that can impact stress and stress-related health outcomes. A study of manufacturing workers during the Great Recession showed that work stress was elevated for remaining workers in downsized plants compared to workers at plants without a high number of layoffs.

Despite the sometimes conflicting evidence presented by dueling economists on the recessions and health dynamic, one thing seems clear: Certain groups of people at certain times in history have been better off during recessions. Unemployment is not always a bad thing. No matter how you view it, there is sufficient evidence in the economics literature to justify digging further into the question of what is going on that might improve population health during periods of high unemployment and a bad economy.

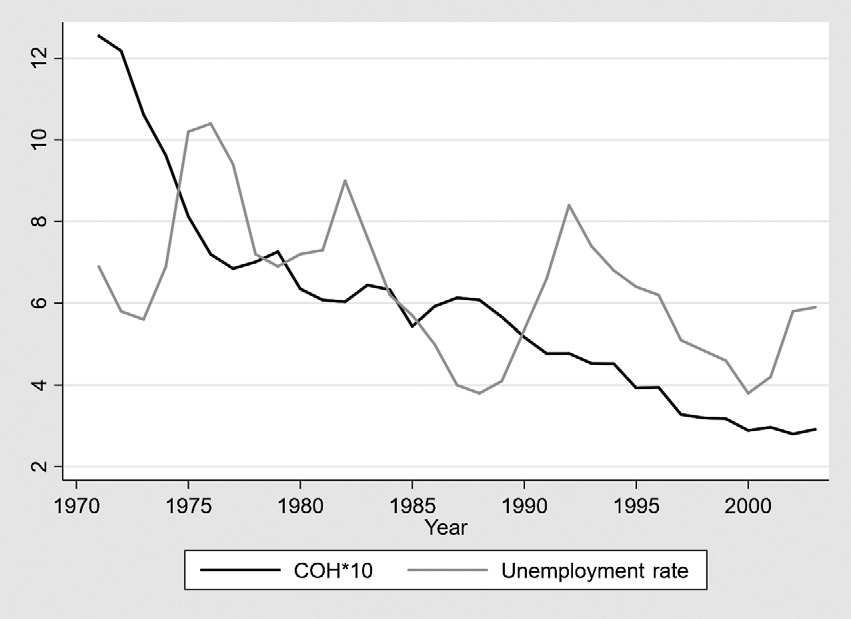

My early research on business cycles and air pollution provided an alternative explanation for improvements to health during economic downturns: When there is less economic activity, there is less air pollution. My work identified that both trucking employment and overall unemployment trends tracked with air pollution at the county level in New Jersey and California, the two states with sufficient historical air pollution data to observe these long-term trends. In California, the size of the unemployment swings observed there during the 1980s and 1990s impacted air pollution concentrations on the order of 10 to 20 percent over that same period. Similar results were observed for New Jersey, where an available marker of diesel pollution (coefficient of haze or COH) tracked closely with economic indicators between 1970 and the mid-1990s. This relationship was particularly noticeable during the major recessionary periods noted in the figure below, where peaks in unemployment were matched with troughs in air pollution.

Reduced exposure to air and other sources of pollution that peak during a roaring economy and wane during a weak one might explain some part of the puzzle of healthier populations during recessions and weaker job markets, but it is certainly not the whole picture. Economists have pointed to a few potential factors, most relying on behavior change and reduced consumption of things that are bad for you like cigarettes and alcohol. The unemployed may also have more time for activities like recreational exercise that are squeezed out by tight work schedules. Of course, there is a counterargument to all of this. Studies also show that stress levels are up during recessions and mental health suffers, and drug and alcohol abuse may rise even when alcohol consumption itself is, on average, down. When there is less money for cigarettes and alcohol, there may also be less money to spend on healthy foods. Depending on the scope, scale, and target industries of any given recession, population health outcomes are likely to vary by individual, industry, and location.

While these factors offer potential explanations for the observed health trends during economic downturns, the complexities of the relationship between economic conditions and population health are far from fully understood. The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have introduced new variables that may have significantly altered this historical relationship. In pre-pandemic times, workers were less likely to switch jobs during periods of economic upheaval. Not so during the immediate aftermath and economic recovery period, where workers quit, retired, and switched jobs at levels deserving of its popular title, The Great Resignation. Understanding the modifying role of increased labor mobility on patterns of recessions and health is a topic worthy of future research. Another potential game changer is that a pandemic-induced recession is unlikely to make people healthier on an aggregate scale since heightened infectious disease risk is the key driver pulling the economy toward the slump in the first place. These are just two caveats that suggest new patterns of human health linked to economic trends may emerge within the altered job market, public health context, and economic landscape of the future. Only time will tell.

Mary Davis is Associate Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, and the author of “Jobs, Health, and the Meaning of Work,” from which this article is adapted.