On Joining and Leaving the Border Patrol

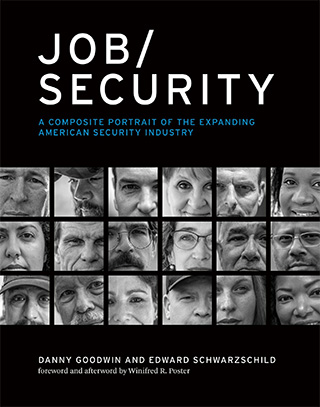

Since 2016, Edward Schwarzschild and Danny Goodwin have been documenting, through photographs and interviews, the lives and experiences of dozens of individuals working in the American security industry. Their subjects range from EMTs and firefighters to veterans of agencies including the CIA, Secret Service, Border Patrol, Marine Corps, Army, Navy, Air Force, FEMA, and TSA. By engaging with personnel at all levels in their career — from former agency leaders to new recruits — they’ve created a composite portrait of an ever-expanding industry, including voices critical of and harmed by the nation’s surveillance infrastructure.

Their book, “Job/Security,” is a culmination of this ongoing project, serving as both a photographic record and an interdisciplinary archive of first-person storytelling. It is intended for anyone seeking to better understand the American security state. Through frank, in-depth interviews and candid photographs, “Job/Security” offers a rare glimpse into the internal complexities of security work and fresh insight into what the encroaching security state is doing to America’s hearts and minds, one worker at time, and to society at large, on an intimately human scale.

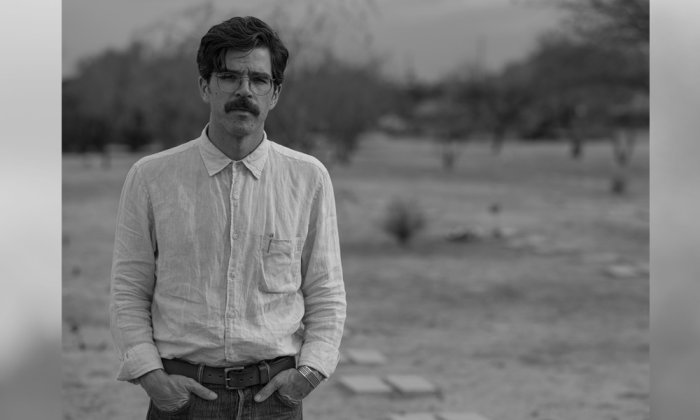

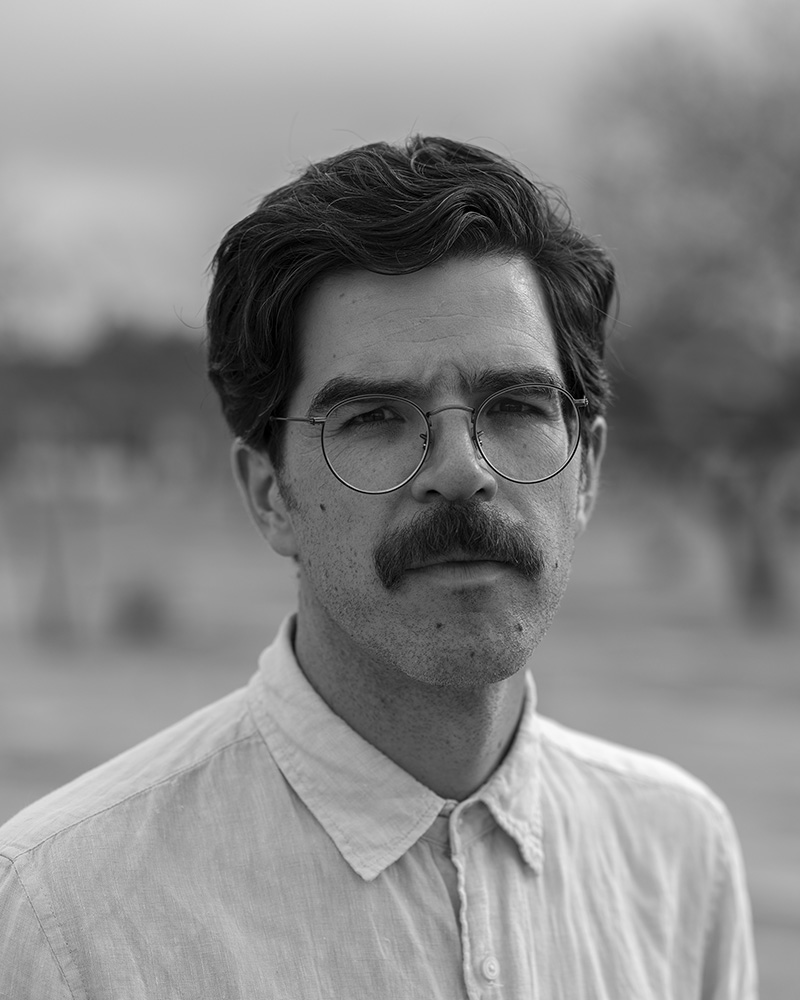

The following transcript of their interview with Francisco Cantú, a former U.S. Border Patrol agent, award-winning author, and professor of creative writing at the University of Arizona, is one of four from the book conducted with former Border Patrol officers (the others include a Patrol Agent and dog handler, a Chief Patrol Agent, and a National Chief). As discussions around immigration and border policy become increasingly polarized, their varied perspectives on what it means to labor on the border are more vital than ever. Schwarzschild and Goodwin’s interview with Cantú took place in December 2021 and has been edited for clarity and length. Throughout the book, the questions of the interviewers were removed in order to create more intimate, uninterrupted personal narratives.

—The Editors

What led me to join the Border Patrol is probably pretty out of the ordinary. It’s a more uncommon path.

I grew up in Arizona. I followed a standard trajectory from high school to undergraduate studies. I decided to study international relations. Then I left home to go to school in D.C., the epicenter of international relations and U.S. diplomacy. For me, growing up in a small town in Arizona, it was such a big shift. I think part of my response to the disorientation of being in a place like that was to turn back towards what I felt I knew a little bit more, or a place and a subject and a topic where I had a little bit of skin in the game. And so, within an international relations degree, I started to focus on U.S. — Mexico relations and border issues.

Studying the border at a place that was so far from the border, through books and studies and research papers and ethnographies, I really had this strange look at the topic and the place. It was like understanding a place that you maybe intuitively know through the eyes of a lot of outside rhetoric, looking at the place as a problem or looking at the place as this question to be answered.

I think my reaction to that when I was coming out of college was that I wanted to go back to Arizona. I knew my interest in the border had only grown. I had studied abroad in Mexico. I had worked at a migration policy institute. I was in this strange situation. When I started to look at how I could go be close to all these issues in a way that was radically different from all the books I’d been reading, I thought, Who’s out on the border day in and day out, 24 hours a day?

I thought about different advocacy jobs or volunteer work. I imagined that those would be weekend trips or that you’d only be out there under certain conditions. And then I was walking around at the university job fair in a huge stadium and going to all these different booths. I remember walking by the Department of Homeland Security booth, the Customs and Border Protection booth, and almost laughingly picking up one of these brochures. That idea weirdly planted itself in my head. I thought, Well, actually, there are very few people who spend more time out in it.

I imagined that I could be a force for good within this agency that I already didn’t agree with, but I sort of accepted as inevitable.

There was a lot of naivete and privilege that went into my thinking at that moment. When I look back on that time, I had this idea as a young person in my early 20s that I could be part of this system. I could step into this system and not partake in the uglier aspects that I knew about and was familiar with. I imagined that I could see and learn, but not be implicated. I imagined that I could be a force for good within this agency that I already didn’t agree with, but I sort of accepted as inevitable. I accepted it as this inevitable part of shaping the reality of the border.

Today, as a writer and a literary critic and thinker, I’m thinking about narrative all the time. And when you look at the narrative of the stories that we grow up with in this country, I think there’s this uniquely American idea that the individual can overcome anything and is the most powerful social unit. We grow up on these stories where one person steps into a system and, against all odds, they’re able to overcome or change it.

As a young person, I had this idea that I could step into this job and that I would learn all of these things and come out with all these answers that nobody else who was a policymaker — or who had written the work I’d been reading in college — had come up with because they’d never done work like that. I imagined I would be able to go on to be this policymaker or this immigration lawyer with a totally different toolbox or bag of tricks.

If I’d gone to a small liberal arts school it might have been different. But the school I went to in D.C. was very oriented around government services jobs. Very oriented around service. The people who came out of my program were angling for State Department jobs, government jobs or research and think tank jobs. That was the abbreviated menu of career options that I think a lot of people like me coming out of a program like that were thinking about.

Now I’ve lived in Tucson for a very long time and I’m involved with so many groups that are doing work on the border, day in and day out, in a completely different capacity. In a moral and ethical capacity. That world just wasn’t as available to me back then. I think that if I had gone to school here, if I had stayed in Arizona, it might have been very different.

I had this foundational, early childhood experience of living in a national park with my mom about an hour and a half or two hours outside of El Paso in west Texas. It was Guadalupe Mountains National Park, one of the least visited national parks in the country. Remote, Chihuahuan desert landscape. We would go to El Paso for shopping. That was the city where we did our urban things. It was an early childhood of being very connected to desert landscapes and caring a lot about the natural world and coming to understand myself in relationship to the outdoors in a big way.

That was early childhood, up until the age of five or six, I think, when we moved away. We moved to central Arizona, an hour and a half north of Phoenix in a small — well, it’s not that small anymore — town called Prescott. My mom got a job with the Forest Service there. It’s a high desert, piñon, juniper, Douglas fir kind of landscape in the middle elevation mountains.

But when I think about the demographics of the place where I grew up . . . now, this is the heart of Arizona’s Trump country. Paul Gosar is our representative. It’s a very white town, where the cowboy myth is larger than life. It’s home of the world’s oldest rodeo.

That was the backdrop to how I grew up. A lot of that sort of mythology. It was an interesting place to grow up in relation to the border because the border was not close like it is here in Tucson. It was not an everyday consideration. It was not a place that people thought about and were involved in on any day-to-day basis. However, it was also not completely foreign or abstract or so distant that it wasn’t at all comprehensible.

My first job was as a busboy in an Italian restaurant. I started in middle school and I kept that job all through high school. Everyone in the back was from the same community in central Mexico, in Guanajuato.

I was growing up in this kind of small, white, cowboy town, and then I started to travel, first in Mexico and then in Europe. Seeing the world beyond this town became this really exciting thing for me as a young person and definitely was kind of the subtext of me choosing to study international relations.

One of the first places I went to when I traveled in Mexico, maybe my freshman year in college, was to the village where all these guys I worked with in the Mexican restaurant were from. I ended up going to the dishwasher’s brother’s wedding. I just happened to be there when he was getting married.

I stepped off the bus like 2,000 miles from where I grew up and I knew somebody and nobody questioned who I was — it was like, Oh, this person works with this other person who left. That was my first experience of seeing the interconnectedness of migrant communities, this living, breathing connection that I think is probably unique to the tail end of the 20th century. There were immediate wire transfers and communication was easier and it still wasn’t so impossible to cross the border in the 80s and the 90s. There was still a more fluid exchange, I think, between a lot of these communities. That was all the stuff maybe swirling behind what became a more academic fascination as I went further into my college years.

I always knew this academic question pointing me into the Border Patrol was uncommon and I think when I talked to friends or family (other than my mom) about the decision, I always did a lot of explaining: Oh, I’m doing it for these reasons and I’m going to find this out. I’m not doing it because I want to protect the country and keep out immigrants or something like that. I don’t believe in that.

Different people bought it or pushed back in different ways. The other people I was going to school with in D.C., they were doing these same kinds of internships at think tanks and government entities. I remember one friend who had an internship at the State Department who was like, There’s this Border Patrol liaison who seems really nice in our office. I’ll ask if you want to talk to that person. That was one of the few people I talked to before applying that was actually from the agency.

We got coffee somewhere in D.C. and had this pretty normal seeming conversation. This person had grown up in Arizona, wasn’t a recruiter or anything, not your typical Border Patrol agent. They were part Asian-American, part Mexican-American. I remember they just talked about, You’ll be outside all the time. You’ll be hiking trails all the time.

And there I was, fascinated by the desert, and having these questions about how do these policies and this enforcement shape our ideas and notion about the landscape? And how has it changed the desert and how is the desert being weaponized in all of these ways? And before those questions were maybe fully formed, it was also just like, Wow, that sounds pretty great to be out in the desert all the time and exploring the outdoors.

I imagined that I would be able to help and have conversations and put people at ease and be a more humanitarian-minded agent.

When I showed up at the Border Patrol Academy, there were lots of guys who’d been in the military or in law enforcement. I signed up in the beginning of 2008, but by the time I showed up at the Academy it was November. This was the tail end of the George W. Bush hiring push and the economy was crashing down. A lot of people who were there were just looking for a good steady job with benefits. There was everybody from 18-year-olds who had only worked at fast food restaurants to early 40s, late 30-year-olds who had run a business for a decade or two before it collapsed because of the economic crisis in 2008.

I remember during the first couple days when we were showing up in Tucson before they sent us to the Academy and they brought us to the station. I remember being with a lot of guys from the Midwest and the East Coast who’d never seen a cactus, never seen a cattle guard. To them this was like the ends of the earth. It was like a purgatory landscape that they were getting sent to patrol at the gates of — you know, like “Game of Thrones.” The wall, or something like that.

I had studied in Mexico. I’d been to different parts of the country where there are traditionally migrant sending communities. I imagined that I would be able to help and have conversations and put people at ease and be a more humanitarian-minded agent.

That idea — yes, it was naïve, but it also wasn’t. It didn’t come out of nowhere. The Border Patrol itself cultivates this idea. There’s a journalist, Debbie Weingarten, who talks about “the militarization of humanitarian aid,” this humanitarian enforcement myth where Border Patrol agents and the Border Patrol in general — especially in the Southwest — talk about the search and rescue component of their work, like We’re the first ones out there who are rescuing people and saving people from the desert and giving them water.

The Border Patrol talks about that a lot and I think that was also something that some of the recruitment literature, or the conversation with that Border Patrol liaison, had given me. Recruiters might see that you’re not a guns and badge kind of a guy and so they pivot to that.

Even once I joined the Border Patrol, I signed up to be trained as an EMT. So, there were these tangible ways in which I was able to prolong my time there and feed this idea that I was doing “good work,” or something good, by providing first aid and doing search and rescue work.

But, of course, all of that comes at the expense of casting into the back of your mind, or not even entertaining the idea, that the reason people need rescuing has completely shifted because of the enforcement policies and the enforcement tactics of the agency. Thirty years ago, people didn’t cross through the middle of the desert. They didn’t make five to 10 to 15-day treks through the most remote parts of the Southwest border because it wasn’t necessary. The whole idea of prevention through deterrence — that wasn’t present in my mind.

Now, I think this idea of being able to feel proud of rescue work as a Border Patrol agent is like being a firefighter and feeling proud about putting out a blaze, but it turns out that blaze was actually started by the fire chief. That’s kind of what it comes down to. These people are there to avoid your presence. They were out there to avoid my presence. So even when I show up and I’m bandaging somebody’s blisters or giving them an IV, bringing them back from a dehydrated state, it’s like, in a very real way, I — or any agent out there — is the reason that that person ended up in that state in the first place.

Still, I would cling to the moments when I was able to come home and feel like I had helped someone. I could cling to those moments as a way to not feel morally implicated or to feel like I was doing something good within the job.

That would happen in my waking life. But all of that would get torn down and torn asunder by dreams and subconscious, unconscious preoccupations. I think that my body, my mind, my spirit knew that was a bunch of bullshit. Or knew that it was this small consolation.

Grappling with that was something that led me to put together “The Line Becomes the River: Dispatches from the Border,” or it led me to do writing in the first place. I think there’s an accumulation in the first part of this book of small encounters, small moments with a different person each time. And a lot of those moments are moments that stuck in my mind because I was having an exchange or a conversation with somebody or “helping” somebody or having someone express gratitude to me. That was always very strange. Because there was this part of you that was like, Wow, that person is thanking me. They feel like I have done something humanitarian to them or helpful to them.

But then you know in the back of your mind that it’s off, that that’s not the whole story. That that’s not where it ends. You’re still sending them back to do it all again.

There were glimmers of wanting to, or trying to, find consolation or some kind of pride in the job. And maybe there were moments. Maybe my hindsight is obscuring moments where I did come home and feel proud. There were definitely moments where you felt exhilarated. A chase and catching a bunch of drugs. It’s easy to imagine that, OK, well, the drug dealers are the bad guys and I’m keeping them out.

You could try to feel good about that for a minute before you realize that the drug war is a bunch of garbage. Even a lot of other agents I worked with realized how silly it was and how small it was.

The Border Patrol instills a military hierarchy from the moment you show up at the Academy. It’s run like a boot camp. They pride themselves on being like a paramilitary police force. They really bill themselves as being somewhere between law enforcement and military.

Your critical question-asking impulses get intentionally broken down during the training process. When I look back at some of these moments when I was observing my colleagues crushing people’s food or slashing water bottles or dumping people’s backpacks out in the desert, that kind of thing. . . . I think I imagined at the moment that by not participating, that that was a moral act or something, just not participating.

But it’s not. You’re completely complicit. You’re wearing a uniform, you’re standing aside while this is happening. A lot of this stuff was happening on my first week in the field. I would see supervisors taking part in this or supervisors literally teaching it and giving the OK. And that hierarchy made it so you didn’t feel like you could speak out or ask questions. I still wonder what would have happened. Would it have been totally futile to speak out?

There are all sorts of moments I didn’t ever write down in my journals. A lot of them are moments that aren’t even in the book. There was this one moment that made it into an op-ed I wrote a few years ago. There was this girl, Jakelin Caal, a 12-year-old girl from Guatemala, who died several years ago. It came out that she was arrested at one of these forwarding operating bases in a remote part of New Mexico and was brought in from the field and detained in this little operating base before agents came to pick up the group that she was apprehended with and take them into the larger station. Probably what happened is that she wasn’t given food and water or any sort of medical attention at the small substation. And so, she died being transported to this bigger station.

I remember reading about that and having this memory return to me of being, again, first or second week in the field, apprehending a group of men in the desert, maybe five people. Bringing them back to the station. I’m a trainee. They could tell that I’m the one that speaks Spanish and they ask me for some water. I say, Oh, yeah, sure.

There was a case of water bottles in the storage room right outside the processing area. I went to bring it into the processing area and my supervisor — my field training agent — sees me walking into the processing area with this case of water bottles and is like, What are you doing?

I said, Oh, these guys asked for water.

She said, They’re fine. Leave it.

I said, I already have the water bottles in my hand. It’s fine. I’ll just go drop it off, don’t worry about it.

And she said, No, that’s an order. Leave it. We need you in the computer room. Come over here right now.

Today I wonder what the fuck could she have possibly done to me if I had said, No, I’m going to give these guys water. Write me up for it. I dare you to write me up for giving these guys water.

Today I wonder what the fuck could she have possibly done to me if I had said, ‘No, I’m going to give these guys water. Write me up for it.’

There are all sorts of ways that they try to get rid of people or push people out. Are you really going to try to push someone out who is saying “No” to those things? There were only a few instances where I ever spoke up, told somebody to shut the fuck up because they were saying something racist. It was always a calculation of, Do I have the rank or social standing to call this person out or try to humiliate them, or something like that.

It’s the culture of the agency. It’s such a toxic culture. It’s such a toxically masculine culture. You don’t show compassion, or talk about feelings. You don’t show weakness. You don’t hesitate or express vulnerability or any of those things.

There were other people. That’s the interesting thing about the Border Patrol. I felt at the time that there were a handful of other like-minded people that I got along with. A lot of the connecting happens through humor or something like that. You develop a sort of dark sense of humor.

There were people who recognized some of the rhetoric and you’re able to poke fun at the idea of, Oh, yeah, we’re fucking heroes because we’re keeping these bundles of schwag marijuana that some middle school kids are going to smoke in their bedroom during a sleepover. You know, like, marijuana? I mean, that was the only thing I ever had a hand in stopping.

Today it’s hard to imagine. Now in Arizona, where I live, marijuana is legal. It’s legal as a recreational drug. You turn 18 and you can buy the stuff. Or maybe it’s 21.

But, at the time, it was absolutely not like that, and there was this idea that I think a lot of people had where it’s like, OK, we understand that these migrants are not criminals. I think there were plenty of people who drew lines that separated the migrants or the people who were coming looking for work from the people who were smuggling drugs. And the drug smugglers are the bad guys and that’s what we’re able to feel good about. That’s where we’re able to believe in this myth that we’re keeping America safe or that we’re standing guard or whatever the hell rhetoric they feed you to make you feel heroic about your job.

But the reality is that the Border Patrol — and this is true for most law enforcement — if you look at the numbers, this is not a dangerous job. These are not violent encounters. The overwhelming majority of your encounters are humanitarian encounters. And if you’re willing to look at it or to have conversations or to think critically, you begin to understand even the people who are smuggling these bales of marijuana through the desert, they’re not hardened criminals. A lot of them are people that struck out on two or three prior attempts to cross the border the normal way with a group and a coyote leading them across. They don’t have any more money to pay for another crossing.

So, you have guys who can’t pay to get across. The smugglers, human traffickers, human trafficking networks are now the same as the drug trafficking networks. That’s a shift that our own drug policies and border enforcement policies have facilitated. Those people will say, “Well, if you carry this bundle of marijuana on your back, we’ll let you cross for free or we’ll give you a discount once you get there.”

You’re not dealing with violent, hardened criminals. You’re not dealing with the smuggling networks. You’re not dealing with El Chapo Guzman out here crossing the desert. These are kids a lot of times, 18-year-old kids or something, who are trying to make a buck leading groups through the desert and bailing the first opportunity they get.

You’re looking at people who are in an extremely precarious situation. The people who are being smuggled, the people who are crossing the border — they’re a lot of times being taken advantage of or victimized — their bodies are being commodified every step of the way. From the moment they leave their doorstep in Central America until even past the time that they arrive, if they successfully arrive. Then they have to pay off the debt they incurred just in order to get to San Francisco or Chicago or wherever they’re trying to go.

There were definitely people I think who saw through that. But I think a lot of people, even people who arrive at or who maybe know the whole time the silly or scary aspects of this work, they might have a family. And they might have a mortgage. And they might not have the option to leave. Or they might not feel like they have the option to leave. Everybody always had the option to leave. But they might not feel like they have the option to leave.

That’s not accidental, either. The Border Patrol, especially in these remote stations like the one where I worked, they know that it’s a hardship for people to be out there. And so, they sweeten the pot. You’re able to climb the ladder quickly. You’re able to get raises quickly. You’re able to promote quickly, especially if you’re out in these “undesirable” stations.

The people who are being smuggled, the people who are crossing the border — their bodies are being commodified every step of the way.

I think there are plenty of people who see the problems, but don’t feel like they have an easy way out. I had a college education. I went into it from the beginning with the idea that it would only be something I would do for four or five years as an extension of my education. I went in with all sorts of privilege. And it was all sorts of privilege that enabled me to so easily leave when I did finally decide to leave.

I imagined I would go into policymaking or that I would become an immigration attorney or something like that. I imagined that I would be coming out of the experience with answers to these intractable questions. I imagined that I was going to get answers to these questions and that I would be uniquely positioned to use those answers in some kind of work or job that I would have afterwards.

But by the time I left the Border Patrol, I think those questions seemed more unanswerable than they had even when I joined. I left with more questions than I came in with. Just the idea that there is an answer to any of this . . . it was obvious that was a fallacy born from afar.

And these problems are also imposed from afar. This border enforcement regime, and the whole way that we think about the border as being problematic, and the whole way we think about this landscape as being hostile — all of that is born from afar or imposed from afar.

Coming out of the Border Patrol — there are several different alternative ways that could have gone. It could have gone in a direction where you just want to get as far away as possible from the place or the subject. I applied for a Fulbright to go to The Netherlands. The Fulbright was to study immigration and asylum seekers in the EU. So it was still connected.

At the end of the day, maybe because of how I grew up, and because of this question of the landscape that was ingrained in me from such a young age because of growing up in the park service, I’ve always felt accountable to this place. Even after I left, leaving the border behind never felt like an option. I was trying to process and make sense of my participation in this violent institution. My complicity. It would be more convenient and easy to leave it behind, but that would also be a continuation of this idea of bottling it all up.

This is all a long way of getting around to my being involved in humanitarian work on the border. Right now, that mostly takes the form of working on projects in detention centers with detained asylum seekers. I don’t know if it’s atonement. There must be an element of that. There must be an element of that subconsciously, implicitly. You know, feeling like it is a way of putting a few weights on the other side of that scale, slowly trying to put in more time and more attention on that side of the scale than I ever did on the other side.

But, really, I think of it now more as a practice. The same way that people think of a religious practice or an intellectual practice or if you practice yoga or meditation or anything like that. It’s just something that you have to show up for daily or weekly or whatever.

This whole system functions by us feeling that the border is far away and that the border is an exceptional, othered landscape that we’re not accountable to. But I live here. It’s a topic, it’s a landscape, that runs through my family. It runs through so many people’s families in this part of the country.

Being involved in some sort of teaching, education, service, volunteer work — I don’t think I’ll ever not do that. I hope I will never not do that as a practice. I don’t know if I believe in this idea of atonement or that idea of balancing the scales. I think that’s probably a false construct. But the idea of it being a practice is much more appealing to me. And of it being about accountability. Being accountable to this place. Being accountable to your life before where you are now. I think we should be accountable to who we were and so that feels important too.

I would really caution anyone to never underestimate these institutions of power that have accumulated their power over the course of centuries. The idea that we can step into them with our own ambitions and our own set of questions and come out scot-free, or the idea that we can change these systems from within — I think that a lot of that is rooted in underestimating those systems and overestimating our power and influence as individuals. I think that the American mythology of the individual is a really toxic one. And I think it’s a myth. I think it’s a complete myth.

What I would tell anybody who’s interested in affecting change is that if you look at history, these institutions rarely, if ever, truly change from the inside. They change in reaction to, most often, intense, sustained people-powered pressure from outside, over the course of many, many, many years or decades.

I think that’s what we are seeing in the last decade with the Black Lives Matter movement and with a lot of the conversations that we’re having about policing in this country, more publicly, more broadly. Not that those conversations are new, because they’re not. But a lot of us are learning about them in ways that we have not before.

The idea that I think a lot of people have after participating in the uprisings in 2020 is like, Oh, why hasn’t this changed? I showed up at my city council meeting. I showed up in the street. I went to these marches. It’s easy to get disillusioned because what has meaningfully changed a year later? Not a lot. Culturally, conversation-wise, a lot has maybe changed. Awareness-wise, maybe a lot has changed. But politically? Policy-wise? Not a lot has changed.

But this is generational work. It’s going to take a long slow shift — a consciousness shift — and sustained involvement and attention. With the border, the biggest thing — and what makes me feel good as a writer — is giving more language to the ways that we think about and talk about the border, enabling people who aren’t from here to have emotional engagement and investment in this place and to be able to think of it the same way that they would think of their home. Or to think about what happens here the same way that they would think about what happens in the next neighborhood over from them.

That seems like the important work moving forward: Not letting the people whose lives are affected by this place be othered. Not letting the place be presented as this dangerous, other-worldly, exceptional landscape, because it’s not. People have been living here in the desert for a very long time and it’s not an inherently violent place. It’s not an inherently hostile place. That comes from what we bring in from the outside.

Francisco Cantú is the author of “The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border.” He teaches at the University of Arizona. This transcript is excerpted from the volume “Job/Security,” a collection of candid interviews and photographs with workers in America’s burgeoning security state.

Edward Schwarzschild is Professor and Director of Creative Writing in the English Department at the University at Albany, SUNY. He is the author of three works of fiction, “In Security,” “The Family Diamond,” and “Responsible Men.” His writing has appeared in the Guardian, the Believer, Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere.

Danny Goodwin is Professor and Chair of the Department of Art and Art History at the University at Albany, SUNY. His photographic, video, and installation work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions and published extensively in the United States and Europe.

Schwarzschild and Goodwin are the co-authors of “Job/Security.”