Long Live the Wonderful and Ridiculous Electronic Signature Pad

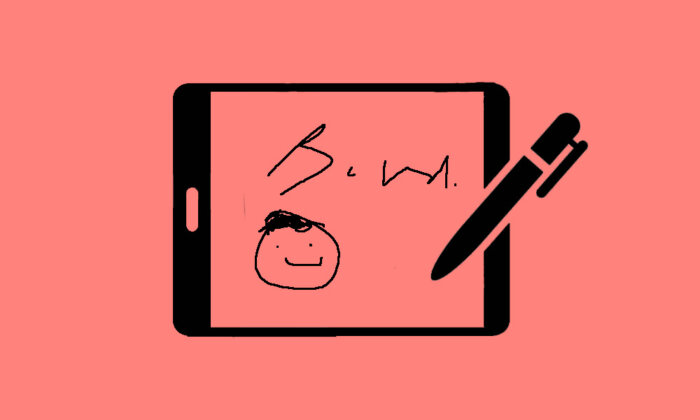

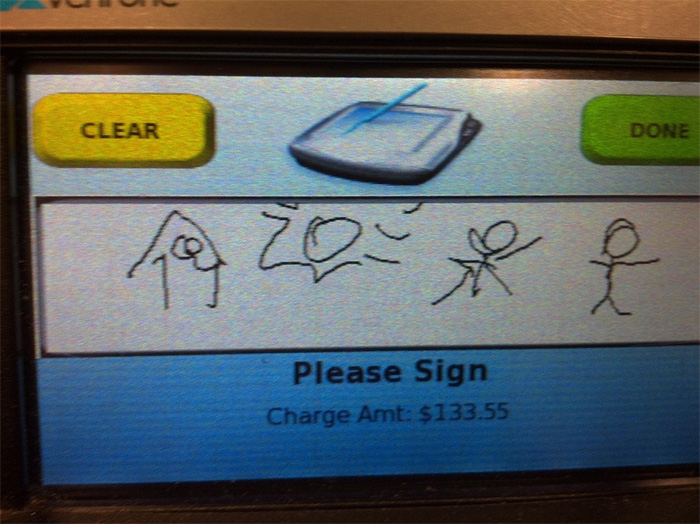

Before it disappears, consider the electronic signature pad, sometimes called the “signature capture pad” (one wonders if there’s a ransom to be paid to release the signature). Signature pads are ridiculous and wonderful at the same time. They’re ridiculous because they don’t work as advertised, like most features of our digital life. Who really takes the time to sign carefully, completely, one’s name on such a device?

“Nearly everything about the process of signing one’s name appears to be in place to dissuade the signer from giving it an honest go,” laments one journalist about both signature pads and their paper-world prototype, the credit card receipt. “Signature pads at stores are terribly awkward, credit card receipt signature lines are often far too tiny, and the people accepting our signatures tend not to care about the appearance of what we scribble.”

Author and prankster John Hargrave dedicated a whole chapter of his book “Prank the Monkey” to paper receipt and payment card antics (putting scribbles, designs, and the words “NOT AUTHORIZED” variously on credit cards and receipts alike). Generally his payments were still accepted. A blogger under the pseudonym Rodan Fizex, meanwhile, devoted an entry to his own signature pad art: When confronted with a signature pad at the point of sale, he drew little pictures (“a dude riding a motorcycle,” “The sun setting a house on fire and people running away and one guy is on fire”). No one challenged his signatures, either.

Signature pads are wonderful, on the other hand, because they evoke other wonders — wonders like the money they are authorized to move, and like the person who supposedly authors them and authorizes that movement, even when that author is not required, as is increasingly the case with signatureless transactions. Signature pads didn’t escape the notice of graphic artist Troy Kreiner and his colleagues. Nor should they escape ours, even if they disappear into the dustbin of payment arcana tomorrow alongside the credit card imprinter or charge-a-plate.

In February 2014, Troy wanted to buy a coffee and biscuit. A clerk gave him a shattered iPad, and asked for his signature and a tip. This inspired him and his colleagues, Jan Buchczik and Kyle Laidig, to produce “John Hancock Was the First Person to Die.” John Hancock, apocryphally but not actually, was the first to affix his signature on the U.S. Declaration of Independence — nice and big, so the king could read it. He’d be the first to die, Kreiner and colleagues joke, if only he knew just how degraded our signatures have become. Ironically, his signature was printed on the document, not signed.

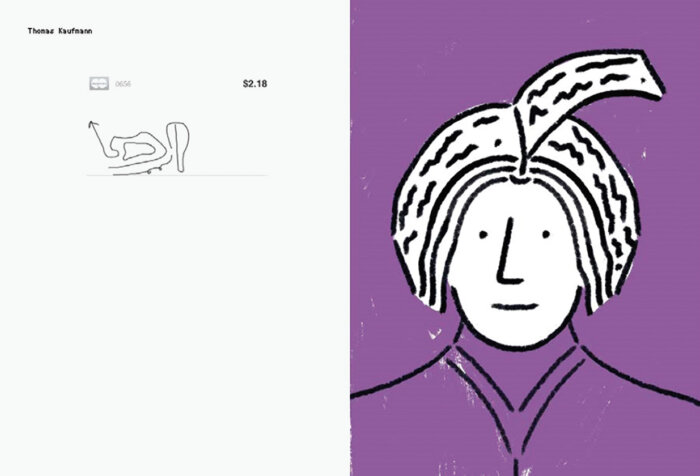

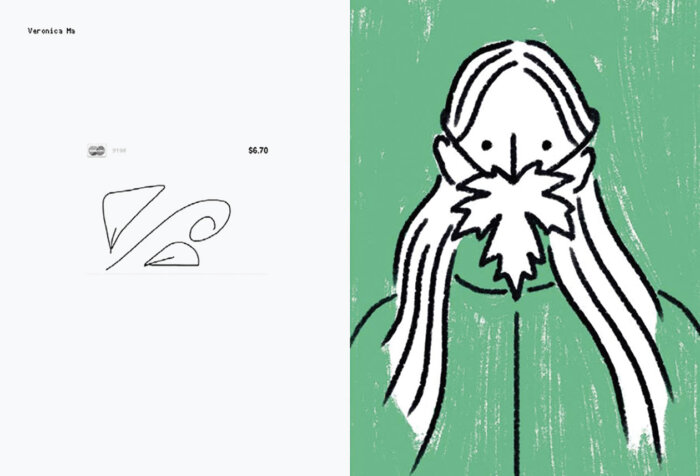

Above: “Thomas Kaufmann.” Below: “Veronica Ma.” Images courtesy of Troy Kreiner.

Nonetheless, in their collaborative work, Kreiner drew made-up signatures as if on an electronic signature pad. Card network logos and prices denominated in U.S. dollars accompany the signatures. Buchczik imagined the people who would have drawn those signatures and created their portraits — imaginary people, like Thomas Kaufmann and Veronica Ma. And Laidig gave them all a place to live, in the pages of a booklet published by Catalogue Paper in London.

There are several sources of legal authority on electronic signatures. The card networks, like Visa and MasterCard, have their own “private network rules.” Both the major card networks have relaxed signature requirements on lower-value transactions and for certain kinds of merchants. As of 2012, you no longer have to sign for Visa purchases under $50. In the United States, the Fair Credit Billing Act sets the maximum liability for the unauthorized use of a credit card at $50. The card networks have gradually been permitting “no signature required” transactions up to this limit, at least for specific categories of merchants where fraud is deemed “low risk” and where increased transaction speed is seen as a benefit to the merchants, like grocery stores. Should a fraudulent transaction occur, it’s just part of the cost of doing business.

For most everyday transactions, you can pay without explicitly authorizing the payment by signing a paper slip or electronic pad. It is as if you are not even there, not even present, with no hand-to-pen required.

Such low-value, low-risk transactions account for over 80 percent of the transactions over the Visa network. For most everyday transactions, therefore, you can pay without explicitly authorizing the payment by signing a paper slip or electronic pad. It is as if you are not even there, not even present, with no hand-to-pen required. The author is no longer required to authorize. That makes the author a kind of wonder, too. Or it kills the author altogether. Hancock was the first person to die, say Kreiner and colleagues. He may well be rolling in his grave.

Most governments have laws on electronic signatures modeled on the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law’s Model Law on Electronic Commerce. Devised in 1996, it allows for almost anything to be considered a signature in a digital environment. It notes that signatures are “intimately linked to the use of paper,” and does so in the context of expressing caution lest its model law unwittingly be linked “to a given state of technical development.” In a world where 3.5 billion people live on less than $2.50 per day, the commission probably has a point, its technological evolutionary determinism aside: Paper still rules.

Remember rock-paper-scissors? Seemingly insubstantial, paper nevertheless always defeats rock. It’s a rule. I always loved that.

Paper similarly still impresses itself around digital signatures. In the United States, the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act, adopted by all but three states, requires that as with a signature on paper, the electronic signature must be “linked or logically associated with the record” signed. The act continues:

In the paper world, it is assumed that the symbol adopted by a party is attached to or located somewhere in the same paper that is intended to be authenticated, e.g., an allonge firmly attached to a promissory note, or the classic signature at the end of a long contract. These tangible manifestations do not exist in the electronic environment, and accordingly, this definition expressly provides that the symbol must in some way be linked to, or connected with, the electronic record being signed.

The analogy to the allonge is worth pausing over. The allonge was the appended sheet containing signatures that would not fit on a promissory note, from the French for a fencing thrust, as the extra page was affixed to the note with a pin or other metal instrument; the violence is perhaps not incidental to the act, as we will see in a moment. In the one dispute over signature pads that I could find in the United States, Labajo v. Best Buy Stores, et al., the main point in contention was that an agreement to subscribe to a magazine was not “logically associated” with the plaintiff’s act of signing.

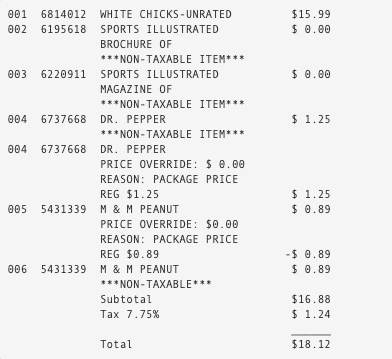

Here’s the scenario. A woman goes into a Best Buy store. She is offered a free trial magazine subscription. She signs a signature pad. Six months later, her payment card gets charged for the automatic renewal of the subscription after the promotional period.

Defendant … alleged that the electronic signature pad used by Plaintiff to complete the transaction notified Plaintiff of the terms of the promotion, but this claim was disputed by Plaintiff. Defendant alleged that the electronic signature pad contained the following language: “Yes! Sign me up for Sports Illustrated’s issue trial offer with automatic renewal. I authorize Best Buy to give my credit or debit card to SI and SI to charge my card for the initial and six month renewal terms.” (Locke Lord Bissell and Liddell 2009, 8)

The court determined that Best Buy needed to produce evidence indicating that the signature on the signature pad was linked or logically associated with the disclosure. But we might ask whether we are anymore linked or logically associated with our signatures on signature pads, or other electronic forms of “signing” documents. This is the question that Kreiner and his colleagues pose, playfully inventing their Kaufmans, Mas, and other characters from signature pad signatures.

In doing so, they are the unwitting inheritors of a minor tradition in American art. In the late 19th century, artists like Otis Kaye, Victor Dubreuil, and Ferdinand Danton Jr. created trompe l’oeil still-life paintings involving breathtakingly accurate images of U.S. legal tender — barrels of banknotes, playful visual puns, and political commentary. Contemporary artist Gayle B. Tate continues this tradition, with his “Time Is Money” series juxtaposing weather-beaten bills pinned to wooden boards while monkeys and Jokers dressed as professors (or vice versa?!) cavort around penciled calculations of profit and loss, watched over by Rich Uncle Pennybags from the Monopoly board game, his face replaced by a clock. These paintings poke fun at the fictions of state underpinned by “fake” money. But don’t be fooled. As many of these paintings explicitly state, while some of these guys were avant la lettre monetarists or are latter-day goldbugs, others were international socialists with a quite different message.

Some of them were also forgers. Danton was, and died in prison and poverty. J.S.G. Boggs drew reproductions of banknotes, obvious fakes, and convinced people to transact with them, with the work of art comprising the whole of the transaction (the bill, receipt, object purchased, change, etc.). Boggs ran afoul of the law in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Forgery brings us back to the signature, of course. In the case of a forged banknote, another artist besides the state is laying claim to the creative potential to make money. In the case of a forged signature, an author besides the person purportedly authorizing a transaction is laying claim to another’s legal persona. Folks on the fringy right in the United States worry about another kind of forgery: the government stealing our signatures and identities — and liberty — by way of signatures. Such people publish ways to subvert signature capture online. At a Target store, press the K and the 8 keys, and the pad will force a paper receipt to be generated. At Vons — a supermarket — hit “Override” and “Enter.”

Some in Silicon Valley laugh off these concerns — although they perhaps share some of the ideology — echoing Malady, and thinking signatures are at best a joke, and at worst an old and costly paper-based inefficiency in this digital age. So just have fun with it and draw whatever you like. Others are hard at work prototyping the use of biometrics to validate signatures captured by signature pads. At least one company touts a service that can supposedly even differentiate people’s sloppy, lazy, pixelated squiggles from one another and link them to specific authors. Your plucky line drawing may authorize your identity after all. A digital signature of a different sort — the hash — is at the core of the operations of the Bitcoin protocol.

The foreclosure crisis coincident with the global financial crisis that began in 2008 taught many former mortgagors a lesson in the technicality of the allonge. The arcana of mortgage paper became newly politicized. Some foreclosed-on homeowners “noticed the signatures of lawyers, notaries, and banking officials appear[ed] to vary” on the reams of documents they received as part of their dealings with brokers and lenders during the foreclosure process. So they created a Web-based depository, WhatSignature.com, “for all consumers who are fighting foreclosure to connect, share and compare signatures, pleadings, and transcripts referencing their personal foreclosure experiences” (the site closed sometime in 2014 but it can still be accessed via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine).

Signatures do matter. That’s why it’s worth capturing them — at the point of sale, in art, satire, and authorizing (sovereign) authority. But they matter for all of these things at once: the commerce and joke, the sovereignty and satire. It is difficult to read Jacques Derrida in the age of the signature pad — and signature pad art — and not smile. Sure, Derrida, Walter Benjamin may have been right, his John Hancock “the sign and seal of divine violence,” its justice beyond, over the horizon of, transcending, the violence of human law. But Hancock would be the first person to die (even though he didn’t actually sign).

Bill Maurer is Dean of the School of Social Sciences at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of, among other books, “How Would You Like to Pay: How Technology Is Changing the Future of Money” and co-editor of “Paid: Tales of Dongles, Checks, and Other Money Stuff,” from which this article is adapted.