What the Science Actually Says About Unconscious Decision Making

In order to “get over” the “uncertainty that perplexes us” when we are faced with important, complex decisions, the American politician and polymath Benjamin Franklin advised his friend the British scientist Joseph Priestley thus:

My way is to divide half a sheet of paper by a line into two columns; writing over the one Pro, and over the other Con. Then, during the three or four days consideration, I put down under the different heads short hints of the different motives, that at different times occur to me, for or against the measure … I find at length where the balance lies; and if, after a day or two of further consideration, nothing new that is of importance occurs on either side, I come to a determination accordingly.… And, though the weight of reasons cannot be taken with the precision of algebraic quantities, yet when each is thus considered, separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less liable to make a rash step.

It was July 1772, and Priestley was grappling with whether to accept the offer of becoming Lord Shelburne’s librarian. He reasoned that Shelburne would be an influential patron and that the salary was good. And yet the upheaval involved in leaving his productive and comfortable life in Leeds made it a tough decision. In the end, after almost six months of deliberation, Priestley accepted the offer.

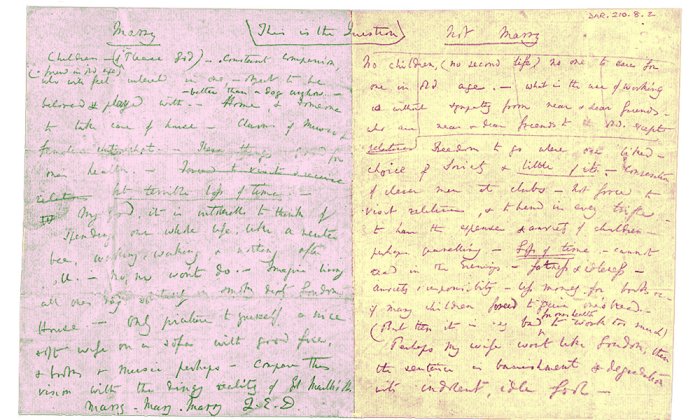

Half a century later, one of the greatest intellects of the modern era was faced with an even more momentous decision. Whether Darwin knew of Franklin’s technique history does not relate, but as the image at the top of the article illustrates, he adopted a similar method. The figure shows a page from Darwin’s journal with two columns headed “Marry” and “Not Marry” separated by the statement, “This is the question.” Below each are various pros, such as companionship in old age, and cons, such as disruption to his work, which entered into Darwin’s cost-benefit analysis of getting hitched. His conclusion (visible at the bottom of the left page): Marry, marry, marry! Q.E.D. Charles and his cousin Emma Wedgwood tied the knot on January 29, 1839, had 10 children, and were married for over 40 years. So at least in terms of family and longevity, getting married appeared to have been a good decision.

Franklin’s advice to Priestley and Darwin’s strategy seem intuitively sensible. When faced with a difficult decision, we should carefully consider the evidence before us, weigh things up, and try to settle on the best course of action. Indeed, the essence of what Franklin called his “moral” or “prudential algebra” is found in many of the formal descriptive and prescriptive approaches to decision making. This advice to rely on explicit, conscious thinking also resonates with our central argument: There is no free lunch when it comes to tricky decisions; you have to do the thinking. The alternative, delegating decisions to the lower reaches of the iceberg and hoping that the unconscious will decide for us, is, we argue, misguided. As we demonstrate throughout “Open Minded,” evidence for the ghost in the machine helping us to decide when to decide is scant; the idea that ripples of activation in our subconscious mind have impacts on our behavior does not bear scrutiny, and evidence for truly unconscious biases seems difficult to find. Moreover, the study of information leakage shows how acutely sensitive we are to the ways in which we are asked to do things.

Evidence for the ghost in the machine helping us to decide when to decide is scant.

And yet a persistent idea in popular conceptions of how the brain and mind work is the notion that thinking can occur outside awareness and that, indeed, harnessing this power of the unconscious brain can lead to better outcomes than striving to think. The argument comes in two guises: that we should go with our gut reaction (blink, or not think) or that we should delegate cognitive activity to an unconscious part of our brain and take a break (sleep on it). Here we explore the evidence for blinking, thinking, and sleeping on it and ask: Is there a “best” way to decide?

Can Too Much Thinking Be a Bad Thing?

A common argument for “going with your gut” or “sleeping on it” is the claim that if we keep deliberating on a decision, we might end up in a kind of analysis paralysis. The idea is that our conscious brain has capacity limitations: It can only hold in mind the magic number of seven (plus or minus two) pieces of information at a time, and thus is hopelessly hobbled when it comes to complex decisions.

A famous experimental example of this too-much-thinking effect involves strawberry jam. The setup was as follows. Participants were brought into a laboratory and were asked to taste five different jams lined up on a table in front of them. After tasting the jams, they were asked to rate how much they liked each one. However, before making the ratings, half of the participants were asked to write down their reasons for liking or disliking each of the jams, while the other half (a control group) listed reasons for a completely unrelated decision: choosing their university major. The experimenters had carefully selected the jams to be representative of a spectrum of quality according to trained experts. The crucial question was whether the participants who were asked to think and provide reasons for their preferences or those who judged without justification ended up with ratings more similar to those of the experts.

The results were intriguing. To obtain a measure of similarity, the experimenters looked at the correlation between the ranks of the students’ ratings and the experts’ ratings. In the control condition, this correlation was a pretty high 0.55 (where 0 is no relationship and 1.0 is a perfect relationship; in psychology, any correlation above about 0.3 is considered informative). But contrary to received wisdom, the correlation between experts and students who had listed their reasons for liking or disliking the jams was only 0.11 — in other words, pretty much no relationship. What happened?

One possibility is that the process of introspecting about why we like a particular jam makes it harder for us to figure out the real reasons because they lie outside our conscious awareness. The suggestion is that although we typically are able to weight relevant information appropriately, for some decisions, it leads to a focus on a subset of reasons that are accessible or plausible (for example, the chunkiness or tartness of the jam) that may not have directly influenced our initial reaction. As a result, this subset of reasons may receive greater (inappropriate) weight than other possible unarticulated reasons, diminishing the quality of the final preference or choice.

One might argue that this suboptimality of introspection only happens when the decision is one that does not lend itself to verbalization. Is it always possible to put into words why something tastes better or worse than something else? Clearly the expert tasters may be able to because they have developed the vocabulary that allows for subtle distinctions. We all marvel at wine connoisseurs for the decorative and inventive language they employ, and expert jam tasters are no different. But even with this factor in mind, there are other features of the jam experiment that should lead us to pause before concluding that thinking leads to suboptimality.

First, it turned out that there was a very high correlation between the liking for each jam expressed in participants’ reasons and their explicit liking rating. So, for example, if a participant reasoned that they really liked the fruitiness of a particular jam, then this was reflected in their subsequent rating. Thus, the participants were internally consistent and could access the proximal bases for their choices even if the reasoning process led them to divert from the “optimal” reasons provided by the experts. This internal consistency may well have been driven by a demand characteristic of the experiment: if participants thought that they might be evaluated for consistency between their reasons and their ratings, then they might have strived to line these up.

A second feature of the experiment was that most of the participants had to taste all five jams first and then provide their reasons, retrospectively, for each one. This delay between tasting and justifying introduces the potential for sensory as well as memory-based interference, which may have pushed people toward relying more on those accessible attributes. Intriguingly, a footnote in the original study lends some weight to this possibility: A few participants in an initial version of the experiment provided their reasons consecutively after tasting each jam, and they showed a stronger correlation with the experts’ rankings. Unfortunately, there were too few participants in this version (only five), and so we cannot draw any strong conclusions from this finding, but the results are certainly suggestive.

The reason for dwelling on the details of this experiment is that the conclusions have gained folkloric status. The jam-tasting study has become synonymous with the idea that “too much thinking is bad,” which in turn leads to the idea that relying on the unconscious mind is good, without always properly considering the evidence. Indeed, the authors, Timothy Wilson and Jonathan Schooler, were more conservative in their original conclusions, stating (in a variation of the famous Socratic advice) that “at least at times, the unexamined choice is worth making.”

This conclusion is fine as far as it goes, but it leaves us hanging in two important ways: We still don’t know which choices require additional reasoned thought, and, even more frustrating, it tells us nothing about where our initial reactions come from. Recall that the ratings provided by participants in the control group lined up pretty well with those of the experts. This overlap might suggest that the experts and the control group participants engaged in similar processes when making their judgments. But what were these processes? If not thinking, evaluation, and attribution, then what? One cannot simply remove the explanation by stating that our reactions bubble up from some inaccessible state. Or perhaps, as we will discover next, you can?

Can NOT Thinking Be Better Than Thinking?

History is replete with examples of dramatic insights or great works of music and literature simply popping into people’s minds. The German chemist August Kekulé had a vision of a snake biting its tail, which supposedly revealed the ring structure of benzene. The French mathematician Henri Poincaré restricted his working hours to allow his unconscious mind to work on tricky math problems in the downtime. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the celebrated English poet, apparently wrote his best-known poem, “Kubla Khan,” while asleep. The melody for “Yesterday,” perhaps the Beatles’ most famous song, came to Paul McCartney in a dream. Sir Paul later claimed that he woke up, fell out of bed (perhaps dragged a comb across his head …), stumbled to his nearby piano, “found out what key I had dreamed it in … and I played it.”

Such accounts, and there are many more, seem miraculous and appear to fly in the face of our claim that there are no murky depths from which fully formed thoughts, ideas, hypotheses, or solutions arise. How can we reconcile these famous examples — which all probably resonate with similar, though probably less momentous, experiences of our own (the crossword clue coming to us in the middle of the night; finally remembering the name of the person we saw on the bus or where we’d put our keys) — with the kind of data we would need to go beyond what are, after all, simply memorable anecdotes? And as the saying goes, the plural of anecdotes is not anecdata.

This point is worth a little further consideration. We hear about the lottery winner who dreamed about the winning numbers, but we never hear from people who dreamed about losing ones. This seems so obvious that it is hardly worth pointing out. What news organization would run a story about the person who dreamed about the wrong lottery numbers? But if we focus only on the surprising, memorable, positive instances, it is difficult to evaluate the claims for miraculous influences. How often did Sir Paul roll out of bed, hammer out some chords, and then think, “Nah, nothing happening there”? We’ll never know. More generally, given the sheer number of times we dream and the myriad contents of those dreams, chance alone will lead some of them to appear consequential. But such statistical flukes should not be the basis for our theories of how the mind works.

The limitations of anecdotal reports — however intuitively plausible they might seem — requires us to reenter the psychology laboratory and look for direct evidence that not thinking about a problem or a decision can actually be beneficial. Dutch social psychologist Ap Dijksterhuis and his colleagues have done exactly that in pursuit of their unconscious thought theory. They claim that being distracted from a decision allows unconscious thought processes to help us achieve a better outcome. The benefits of this process are argued to be strongest when a decision problem is complex — those with multiple options and attributes—because unconscious thought does not suffer from the capacity limitations that hobble conscious thought.

So what are these complex decisions that benefit from a period of unconscious thought? In the lab, researchers have used hypothetical versions of decisions like choosing a new car, an apartment, or a roommate. Take the example of deciding what car to buy. In the standard experimental paradigm, participants are presented with information about three or four fictional cars (for example, a Hatsdun, a Kaiwa) described by 10 or more attributes (mileage, trunk space) and are asked to choose the “best” one. Each car has a different number of good and bad attributes (perhaps the Hatsdun might have good mileage, trunk space, lots of cupholders but a high price). When this information is presented to participants, things get a little odd. Instead of providing the list of attributes in a convenient table, allowing for an easy comparison of options, the information appears sequentially, one at a time in the middle of a computer screen and typically in a random order about the three or four different cars.

The next part is where the experimenters try to mirror the think, blink. or sleep-on-it methods. One group of participants is told that they will be asked about their car choice later, but first they need to solve some anagrams. This period of distraction is claimed to facilitate unconscious thought. In essence, you allow your brain to sleep on the car choice decision for a few minutes (unconscious thought takes care of it for you) while your conscious brain grapples with working out what LOPTI might mean. Those asked to “think” are also told that they will need to choose a car a little later but that they should use the next few minutes to really consider their choice carefully. They have to do this, however, by relying on their memory for the randomly presented car attributes; they are not allowed to review the information. Finally, the “blinkers” are asked for an immediate car choice as soon as the final attribute has disappeared from the screen.

Who makes the best decision? The sleepers, the thinkers, or the blinkers? The answer might come as a surprise: Distraction appears to lead to better choices than either conscious thought or an immediate decision. For example, in one early study published in the highly prestigious journal Science, 60 percent of participants chose the best car after being distracted compared to only 25 percent following conscious deliberation. Proponents of unconscious thought theory explain this surprising pattern of results along the following lines. The bombardment of all 40 pieces of information about the cars (four cars each with 10 attributes) in a random order is simply too much for us to comprehend in a methodical, conscious manner, and so when we are asked for an immediate decision or, worse, forced to cogitate on a loose collection of impressions (Was it the Hatsdun or the Kaiwa that had lots of cupholders?) we fail miserably. Note that a 25 percent choice rate of the best car when there are only four options means that people chose randomly. Unconscious thought is claimed to have increased capacity and superior information weighting relative to conscious thought. Thus, while our attention is held by anagrams, the unconscious acts in the background to organize, weight, and integrate information in an optimal fashion, ready for the answer to bubble up once we are asked.

This kind of explanation is anathema to our argument: nothing can bubble up from the depths of the iceberg because there is no active cognition — of the kind that leads to decisions, judgments, and preferences — occurring below the limen of awareness. So how do we reconcile this apparent advantage for unconscious thought with our central proposal? One route to reconciliation is to explore alternative explanations of the effect that do not require recourse to ill-defined unconscious processes. For example, how do we know that unconscious thought leads specifically to superior weighting of information? In many of the experiments, the importance of attributes, and thus what constitutes the “best” car, is predefined by the experimenter. Often this is done in an implausible manner by, for example, deeming the number of cupholders in a car as important as the fuel economy. With these experimenter-defined weighting schemes, it is impossible to know if the “best” choice is indeed the one favored by all participants. (I might think that cupholders are twice as important as fuel economy; you might think the opposite.)

Studies find that regardless of the mode of thought — conscious, unconscious, or immediate — the majority of participants chose the option predicted by summing up their subjective importance ratings.

In fact, subsequent studies — including one of our own — that asked participants for importance ratings for the attributes (for example, “How important are cupholders for making your decision?”) found that regardless of the mode of thought — conscious, unconscious, or immediate — the majority of participants chose the option predicted by summing up their subjective importance ratings. In other words, I choose what I like (not what the experimenter thinks is best), and it does not matter how you make me think about it.

A second route to reconciling apparent unconscious thought advantages with our perspective is to question the reliability of the whole enterprise. Following the initial high-profile publication of the cars study in Science, a large number of researchers engaged in further investigations to see just how far the deliberation-without-attention idea could go. It is fair to say that the results of these studies were mixed: Many researchers (us included) found that they could not replicate the basic effect — often finding no differences in terms of the choices made by the thinkers, blinkers, and sleepers.

The final nail in the coffin for the theory was a large experiment with almost 400 participants that attempted to determine once and for all the circumstances under which not thinking might be better than thinking. The team, also Dutch (but not involving Dijksterhuis and his colleagues), included a variety of conditions to try to pinpoint the sweet spot for unconscious thought. For example, some previous work had suggested that the distraction task engaged in during the period of not thinking needs to be “just right” in terms of its difficulty — not too hard but not too easy, the idea being that unconscious thought might need a little bit of attention, thereby making lighter distraction tasks more fruitful than taxing ones. Thus, among many other things, this large experiment included groups given either difficult anagrams or an easy word search problem during the distraction period. Did this make any difference to the quality of the decisions? None whatsoever. The bottom line from this study was that regardless of the mode of thought, the type of distraction task, the time for (non)deliberation, the complexity of the decision, the participants’ goal — the list goes on — 60 percent of participants on average chose the “best” option. There was no advantage of unconscious thought. Moreover, a meta-analysis indicated that existing evidence for unconscious thought came from studies with relatively small numbers of participants, thus casting doubt on the reliability of the effect.

Where do these investigations of jam tasters and hypothetical car buyers leave us? Are we any closer to knowing how best to decide? Before answering this question, let’s turn to another source of evidence that might shed some light. The studies we’ve discussed so far have tended to focus on what people do after they’ve been given some information (jams to taste, cars to choose) and have asked how much time they should devote to (not) thinking about the options in front of them. But what about a more fundamental question: How much information do we need in the first place for a good decision? Should we follow Franklin’s advice and keep searching until “nothing new that is of importance occurs on either side” of the ledger, or should we rely on a brief glimpse?

Blink, Don’t Think?

Perhaps the powers of the unconscious are revealed not when our thinking per se is curtailed but when the evidence we have before us is scant and impoverished. Only then do the processes at the bottom of the iceberg come into their own.

“Thin slicing,” proposed by social psychologist Nalini Ambady (and popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his best-seller “Blink”), captures the idea that very brief observations of behavior can give rise to surprisingly accurate inferences. The typical study involves participants watching or listening to brief clips of one or more people about whom they are then asked to make a judgment.

For example, one early study showed participants 10-second clips of 13 college teachers and asked them to rate each teacher on a variety of characteristics (likable, dominant, confident, warm). These ratings were then compared to an assessment of the overall effectiveness of the teacher provided by students who had been taught by the same teacher for an entire semester. Remarkably, these 10-second clips were enough for the observers to get a good sense of the teachers. The ratings for traits like optimism, enthusiasm, and confidence correlated very strongly (more than .70) with the end-of-semester judgments. A subsequent study showed that reducing the slice down to two seconds did not make observers any worse.

For Gladwell, these kinds of demonstrations are evidence of the “ability of our unconscious to find patterns in situations and behaviors.” But is it really the unconscious at work here? Let’s dig a little deeper into the details. In his book, Gladwell discusses (at some length) the work of John Gottman and colleagues on judging the success or otherwise of marriages on the basis of brief videos of couples interacting. A typical video might feature a 15-minute discussion about a couple’s new dog; that is, couples are not directed to talk about their marriage, but the topic they choose might reveal some insights into how things are going. Careful inspection of these videos reveals hints that can apparently predict marriage longevity with high accuracy. But here’s the thing: It is careful inspection, not a mere glimpse or blink. In a telling passage, Gladwell notes that when he tried to judge the success or failure of couples in a set of videos sent to him by Gottman, he did no better than flipping a coin. If the unconscious is so talented at sifting the wheat from the chaff, of doing the organizing and weighting of information, then why was Gladwell such a poor judge?

The answer in part lies in the fact that to become a marriage-longevity whisperer requires knowing what to look for in the videos. Gottman uses his specific affect coding system (SPAFF) to document all of the emotional tics and traits that can be gleaned from the verbal and non-verbal behavior of the couple. Far from an untrained eye viewing a “thin slice,” this coding system is a painstaking attempt to work out the ratio of positive and negative emotions displayed by the couples. Only with this information carefully recorded can one attempt to predict longevity.

What about naive observers like Gladwell? Can they do better without full-blown training on the SPAFF? One study suggests they can, but again, not just from a glimpse. The study (which had only five raters) gave each participant an emotion checklist (not as in depth as the SPAFF but still a pointer as to what to look out for) and then conveniently divided the 10-minute interactions into 30-second segments. Raters watched each segment twice — once to focus on the man’s behavior and once on the woman’s behavior. These pooled ratings were about 80 percent accurate in predicting marriage success. So, yes, with a list of what to look out for and the time to reflect and record the behavior of each member of the couple, raters do appear to pick up some relevant features for predicting marriage longevity. But this hardly sounds like the unconscious finding patterns in situations and behavior.

Nalini Ambady’s study of the college teachers had a similar setup. Participants were told what to look for — whether the teacher is confident, dominant, attentive, and so on — and were given time to record their ratings of each clip before the next one was shown. They also had three attempts at it: three 10-second clips for each teacher. This is not to belittle the results; it is simply to question what role the unconscious plays in their explanation.

In a follow-up to the teacher rating study, reported many years later, Ambady tried to find some more direct evidence for the mechanism underlying the success of thin slicing. She reasoned that if thin slicing reflects nonconscious, automatic processing, then two predictions follow. First, increasing cognitive effort or load while people watched the video clips should not affect performance. Second, encouraging deliberation such as providing reasons for one’s ratings should make people less accurate. The logic here is similar to that of the jams and car choice studies. If thin slicing taps processes outside our awareness, then occupying conscious thought with additional cognitive load won’t make judgments worse; according to Ap Dijksterhuis, they might even improve. And introspecting on why a teacher is effective might lead you to focus on irrelevant details that cloud your judgment.

To test these ideas Ambady compared four separate groups of participants. One group just made a rating of effectiveness; a second had to count backward in 9s from 1,000 while watching the clips; the third group spent one minute listing the reasons for their ratings following each clip; and the final group sat for one minute between seeing the clip and making their rating (this was a control group to assess whether a simple delay — rather than generating reasons — would have an effect). What happened? The raters who had to report their reasons did much worse than the other three groups, but the immediate, distracted, and delayed groups were all about as accurate as each other. There is certainly no evidence from this experiment that being distracted makes you better — so no support for unconscious thought proponents — but in line with the jams study, it seems that introspection can sometimes hurt. Is this then evidence for an unconscious influence? In reflecting on these results, Nalini Ambady concluded, “The present work does suggest that sometimes it is dangerous to think too much — at least while evaluating others in a familiar domain.” This conclusion echoes Wilson and Schooler’s claim that at times, “the unexamined choice is worth making.” The question is, Why?

Is Intuition Unconscious?

The preferred account seems to be that these too-much-thinking effects are consistent with people lacking conscious introspective access into the “true” bases for their attitudes and subsequent choices. But nothing in these experiments necessitates that conclusion. As we’ve seen, the key feature of these studies is that participants who are invited to give elaborate reasons end up with choices that are less aligned with those of someone making an impressionistic choice. While such studies support the idea that preferences are constructed, labile, and influenced by deliberation, they surely do not force the conclusion that some influences on choice lie outside awareness. Moreover, there are precious few studies demonstrating that giving reasons causes people to make objectively worse rather than simply less aligned choices.

Albert Einstein once noted that “intuition is nothing but the outcome of earlier intellectual experience.”

Choices made intuitively and ones accompanied by an analysis of reasons are, we contend, accompanied by awareness of the proximal basis for that choice. The fact that this proximal basis might not be the same in the two cases does not imply that the unexamined choice was mediated by an unconscious process. We discussed this idea of a proximal basis for choice in another chapter of our book when discussing diners on a blind date. Your choice of a garlic dish from a menu is driven by the proximal belief that it is healthy. There may also be some distal influence that causes this proximal belief — your mother told you it’s a good source of antioxidants when you were a child — but that has no bearing on your decision in the moment.

But hold on. Are we having our cake and eating it too? We’ve said that there is no evidence here for influences from the depths of the iceberg, but we are still describing some choices as being made intuitively while others are the product of deliberation. Isn’t intuition simply an unconscious process in a different guise?

No. Herbert Simon, the profoundly influential Nobel Prize–winning economist, computer scientist, and psychologist, famously wrote that intuition is “nothing more and nothing less than recognition.” In a similar vein, Albert Einstein once noted that “intuition is nothing but the outcome of earlier intellectual experience.” In other words, intuition is something we can rely on when we are in a highly familiar domain where we recognize what to do. Some decisions may appear subjectively fast and effortless because they are made on the basis of recognition: The situation provides a cue (for example, no clouds in the sky), the cue gives us access to information stored in memory (rain is unlikely), and the information provides an answer (don’t take an umbrella). When such cues are not so readily apparent or information in memory is either absent or more difficult to access, our decisions shift to become more deliberative. The two extremes are associated with different experiences. Whereas deliberative thought yields awareness of intermediate steps in an inferential chain and of effortful combination of information, intuitive thought lacks awareness of intermediate cognitive steps (because there aren’t any) and does not feel effortful (because the cues trigger the decision). Intuition is, however, characterized by feelings of familiarity and fluency. Again, the simple point is that in neither situation do we need to posit magical unconscious processes producing answers and solutions from thin air (or murky depths).

But what about Paul McCartney and his dream about “Yesterday”? Surely that’s solid (anecdotal) evidence that fully formed solutions can emerge from the unconscious? Well, not really. It turns out that McCartney did not record “Yesterday” for another 18 months after his dream; it took that long to work it up into the classic that it became. It started off being known as “Scrambled Eggs” — with the oh-so-catchy lyric: “Scrambled eggs. Oh my baby how I love your legs.” What came to Paul in his dream (and perhaps to many of those other famous beneficiaries of so-called insight) was not so much the fully fledged song as the suspicion of a good melody.

Thinking, it turns out, can be pretty useful, but we have to bear in mind that focusing closely on the reasons for our choices can cause those choices to change, as in the jams example. Thinking can appear subjectively fast and intuitive or slow and deliberative, but this distinction has no bearing on the involvement of factors outside our awareness. In fact, although the notion of dual systems of thinking has become pervasive, it does more harm than good.

Ben Newell is Professor of Psychology and Deputy Head of the School of Psychology at UNSW Sydney. He has published many articles and book chapters on human judgment and decision making. David Shanks is Professor of Psychology and Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Brain Sciences at University College London. He has published many articles and book chapters on learning, memory, and decision making and is coauthor, with Newell, of “Straight Choices: The Psychology of Decision Making.” Newell and Shanks are also the authors of “Open Minded,” from which this article is excerpted. The entire book can be freely accessed here.