The Wet History of Media in the Bathroom

In the 1980s, as Americans were swept up in a fitness craze and growing obsession with personal wellness, self-betterment projects extended from the outdoors to domestic interiors. Bathrooms in particular got larger and larger (some large enough to do cartwheels in), as did bathtubs and showers. Interior designers promoted renovating one’s bathroom to feature the latest high-tech gadgets and encouraged people to reconceive of these spaces as “luxury spas.” These architectural changes imagined that media practices and hygiene practices could seamlessly coexist. Over time, bathroom culture expanded well beyond basic hygiene.

As Alexander Kira notes in his classic study on bathroom design, activities including “smoking, eating, drinking, reading, watching television, listening to the radio, telephoning, playing, masturbating, and so forth” were treated as increasingly acceptable and normalized. Thus, he writes, “The distinction between what is a primary and what is a secondary activity [in a bathroom] is sometimes blurred by motivations.” He offers the case of a “mother with several small children who takes her favorite magazine with her to read while taking a bath” and explains that it was difficult to sort out whether the bath or the magazine reading held greater importance for that mother. What activities were “allowed” in bathrooms depended on many factors, such as the historical moment, a household’s socioeconomic status, roles played in a household (and number of people in the house), gender norms, architectural features (how many bathrooms and square feet?), and attitudes toward dirt, germs, and filth.

To a large extent, media technology use in bathrooms had long represented a luxury or privilege not afforded to many lower- or middle-class folks. But this wasn’t a sheer affordability matter; as with telephones in the early 1900s, people commonly rejected such devices even when they were available because they treated bathing as a sacred practice separate from everyday life’s hustle and bustle. These social interpretations intersected with (and perhaps even furthered) technical limitations.

While radios were designed for portability in the 1940s and 1950s, manufacturers identified liquids as their one limitation. A 1947 Zenith ad, for instance, proclaimed that “Zenith Portables won’t play under water … but they will play everywhere else!” If the aquatic radio seemed an impossibility when compared to all the places a radio could go, then so too did the bathroom device; it was highly unusual to put radios to use there given the potential for electrocution and the limited space available in most bathrooms away from water elements.

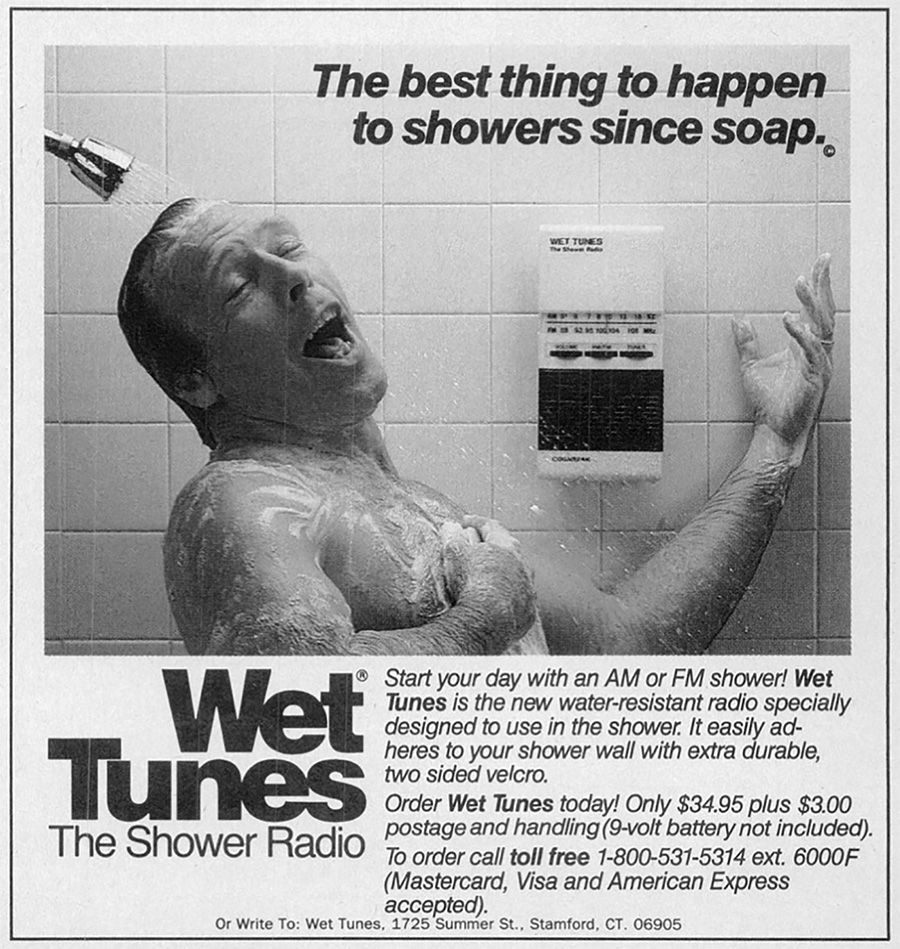

Thus, by the 1970s, products made for bathroom consumption were uncommon novelties, like the Sears, Roebuck and Company radio that could affix to walls or fit on shelves. A similar model made by Windsor, aimed at the “executive,” attached to the bathroom wall via adhesive strips, framing the toilet paper roll. Many of these devices ran on batteries, mitigating the need for cords that previously posed a danger with wetness. Radio manufacturers found a new willing audience among bathers in the mid-1980s, however, amid the cultural turn toward health and fitness. They proposed that bathroom showers could serve as a new media consumption site and that the radio apparatus itself, like the Sports Walkman, could get wet as opposed to merely operating at a safe, splashable distance from water. Targeted particularly at people in their teens to 30s, shower radios were relatively inexpensive (typically between $20 and $35) and featured plastic housings and water-resistant coating for wall-mounted use. Some of the most well-known brands included Wet Tunes by Salton, Soaprano by Biforia USA Inc., and Splash Dance by Pollenex. By 1985, Adweek forecasted that corporations would sell 1.5 million shower radios that year ($30 million in sales), with a projected 1986 increase to 2 million units ($40 million in sales).

These devices grew quickly in popularity due to their low price, plastic construction, and the ways that they reinforced and promoted entertainment as seamlessly meshing with hygienic and fitness cultures. Newspapers, magazines, and department stores featured them as ideal Christmas gifts, and corporations often included them as sweepstakes prizes. They constituted a type of gimmick, which spawned many iterations in the mid-to-late 80s, including Tub-Tunes, Nep-Tunes (meant for the pool), and Hit Tunes. Nevertheless, Lester Gribetz, an executive vice president and general manager of housewares for department store Bloomingdale’s, observed their fleeting trendiness; sales fell in half from one year to the next, once “hot” and then not. Consumers didn’t take such products seriously as a necessity — unlike the battle-ready wristwatch or the impervious camera — but rather they considered them an accessory aimed at a particular demographic who wanted to make the bathing experience more fun.

Shower radios generated interest because they promoted an ideal of the “good” body as a clean one, suturing together washing with media content.

Still, shower radios generated interest because they promoted an ideal of the “good” body as a clean one, suturing together washing with media content. Their advertisements and packaging featured young, white people who looked to be in their 20s having a good time while cleansing themselves, encouraging an active body that didn’t swim or hike but liked to “dance” while bathing. Another recurring theme featured singing or whistling in the shower — a practice common long before these devices’ advent. Consumers’ familiarity with singing in the shower helped to argue that an already existing everyday life routine could easily merge with a water-resistant media technology to allow for carefree consumption. Although shower radios were not pitched primarily as practical technologies, manufacturers did frame shower-listening as a strategy for keeping up with consumption without missing out on sports updates or news content, somewhat akin to uninterrupted timekeeping or disruption-free phone calls. Similarly, Salton promised with its Wet Tunes that “you won’t have to miss a beat” by not hearing “today’s number one hit” on the radio due to bathroom activities, a concern described by bathers more than 40 years earlier.

Notably, this marketing did not employ any militaristic language to describe the music player’s wet encounters. In fact, Splash Dance’s packaging and TV commercials and Wet Tunes’ print ads hardly dealt with liquidity at all. Aside from a mere mention of “water resistant,” the promotions did nothing to stress toughness, ruggedness, or elemental antagonism. Rather, the device plainly affixed to the wall as it received a splash from the showerer’s wet head, an unquestioned media partner. This acclimation differed from the submerged wristwatch (in fish tank, pool, or ocean) because it didn’t construct the media technology or its environs as exotic or dangerous. Conceiving of a splash or spray as trifling and ordinary, the radio’s plastic housing simply carried on. At the same time, the bather in a familiar (and feminized) domestic context did not perform any great tests of her person like the diver, hiker, or swimmer; mundane washing meant business as usual. This perspective fit in with manufacturers’ goals to make music listening routine rather than extraordinary.

If shower radios functioned as inexpensive gimmicks of the moment, then at the other end of the spectrum, bathroom product manufacturers envisioned high-end luxury bathtubs that could incorporate music — as well as many other media and information technologies — into the bathing experience. These all-in-one designs remained far out of reach for the average buyer (and were significantly different from the cheap plastic rope or wall-mounted radios sold at Filene’s or Marshall Field’s department stores), but they represented an imagined future of fully technologized and mediatized bathrooms. American Standard’s $25,000 tub, the Sensorium, promised such an experience, with a keyboard of 22 different controls that allowed one to speak via a telephone or intercom, control a home’s locks, play music, and watch TV. Another product, WaterJet Corporation’s “The Bath Womb,” offered a similar menu of options. Whether such features promised ultimate relaxation, or annoying disruption, proved disputable. Described one reviewer of the tub:

Lean your head against the water pillow, which gives a gentle massage; turn on the stereo system to play soft music over the water-resistant speakers on either side of your head; and start a gentle whirlpool from the nine water jets in the tub.… If you could store food rations in the tub, you might stay weeks. What could possibly shatter such bliss? Again, electronics provide the answer. You glance at the built-in digital clock and realize that you are late for an appointment. But before you can get out of the tub, your boss calls on the waterproof phone to say you will not be paid for three weeks of last year’s vacation time that you didn’t use.

This conflicted account of a hypothetical bath in “The Bath Womb” suggested how media technologies accrued conflicting meaning. On the one hand, soft music provided the necessary context for relaxation in a protected, womb-like space; on the other, the pressures of the clock and phone intruded on the bather’s “bliss,” transforming wellness time into work time. One’s media ideologies — which dictated how people thought about what different media types were for and how they were interpreted — influenced these perceptions. While many agreed in the popular press that “there’s more to [bathrooms] than just keeping clean,” not all could reconcile the introduction of media technologies (especially electric and electronic ones) in these realms when they metaphorically “leaked” other daily life pressures into a seemingly sequestered space. This perspective echoed one from the early 1900s that painted telephones and their ringing as unwelcome intruders on the sanctity of bathing.

Bathing itself could connote many things, including health (cleansing germs), self-care, or sensuality and sexuality, and indeed bathrooms possessed a long and storied history in relation to pornography, sex toys, and illicit scribblings on the walls of public stalls. Thus, what media was “allowed” in bathrooms and how that permission intersected with social norms, gender, and taboo practices suggested the multiplicity of meanings that wetness could provoke.

An iconic scene from the 1990 film “Pretty Woman” reflected this complexity, when a bathing woman became the object of a man’s desire. Featuring Julia Roberts as a likable sex worker taking up with a successful executive (Richard Gere), one scene features Roberts bathing in Gere’s tub full of bubbles while singing enthusiastically to Prince’s song “Kiss” on that famously plastic yellow Sony Sports Walkman with headphones. Lost in the music, she’s unaware of Gere’s prolonged gaze. The music acts as occasion for getting lost in the moment — a kind of double immersion in liquid and media content. Like the shower radio advertising campaign, the film also offered a very different conception of water-resistant media from that of the wartime wristwatch, evoking feminized relaxation and vulnerable (naked) enjoyment instead of armored protection. Where repairers had warned against women bathing while wearing their watches, the film depicted the Walkman unproblematically in terms of its wetness: Though it sat on the edge of the tub, the headphone’s cords dipped unflinchingly in soapy suds. This normalized wetness corresponded with a quite sanitized sexuality that was neither overtly risqué nor threatening, with Roberts’s body covered up with bubbles and her character positively transformed through the course of the film.

“Pretty Woman” positioned the character not as a failed caretaker neglecting her device’s needs, but rather as someone who prioritized her own self-care with the right acoustic accompaniment. But if this scene idealized this wetness, then it also depicted the sex worker caught between two classed and gendered worlds: The Walkman and the bathtub weren’t hers, after all. Singing in the tub with the portable music player helped to habituate Roberts into the hedonistic, swanky lifestyle that a business tycoon could offer a sex worker when she adopted his liquid practices. The acclimated device made her at home in someone else’s wet world and liquid routine. After all, media technologies may have grown more comfortable with water — though certainly not for everyone alike.

Rachel Plotnick is a historian and cultural theorist whose research and teaching focus on information, communication, and media technologies in everyday life. She is the author of “Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing” and “License to Spill: Where Dry Devices Meet Liquid Lives,” from which this article is adapted. An open access edition of “License to Spill” is available for download here.