The Objects That Hold Our Histories

In Harriet Jacobs’s “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” (1861), she describes a tool, a gimlet, that was left in a crawlspace in her grandmother’s house where she found refuge from enslavement for seven years. She says:

One day I hit my head against something, and found it was a gimlet. My uncle had left it sticking there when he made the trapdoor. I was as rejoiced as Robinson Crusoe could have been in finding such a treasure. It put a lucky thought into my head. I said to myself, “Now I will have some light. Now I will see my children.” I did not dare to begin my work during the daytime, for fear of attracting attention. But I groped round; and having found the side next the street, where I could frequently see my children, I stuck the gimlet in and waited for evening. I bored three rows of holes, one above another; then I bored out the interstices between. I thus succeeded in making one hole about an inch long and an inch broad. I sat by it till late into the night, to enjoy the little whiff of air that floated in. In the morning, I watched for my children.

Until I read Jacobs’s account of her time in that cramped interstitial space, I had exclusively known a gimlet to be an elegant cocktail. But when I read her chapter “The Loophole of Retreat,” I learned that a gimlet is also a small T-shaped tool with a screw tip for boring holes. Jacobs used a gimlet to bring light and air into the garret where she was being hidden for her protection. The space was only nine feet by seven feet, and “the highest part was three feet high, and sloped down abruptly to the loose board floor.” With the gimlet, Jacobs created the holes through which she could observe her children.

This tool seems perfect in size and function for many things. I started thinking, wouldn’t it be wise to carry a gimlet everywhere one goes? Wouldn’t it be a good intention for a Black woman to walk around with a gimlet sewn in the hem of a sleeve or, depending on its size, tucked like a $20 bill just inside her bra?

Perhaps one should not only consider carrying an actual gimlet, but also to have a metaphorical gimlet at one’s disposal, a little something for those times when matters feel precarious and unsafe.

Imagine that for a second. Think about a time when you were experiencing darkness and you needed light to shine your way. Imagine being able to access your little gimlet in those moments or in those spaces when and where you need to retreat, you need a retreat. You could reach for your gimlet and, like Jacobs, you could bore three rows of holes, one above another, and you could, amid your situation, quietly, unbeknownst to anyone, succeed in making at least one hole about an inch long and inch broad to enjoy a breath of fresh air.

I have been thinking about narratives, like Jacobs’s, or stories as paths for self-determination, and about memory as medicine.

With that in mind, let me introduce you to Eadie Mae Jackson, also known as my mother or my maker. She was born in 1938 in rural Mississippi to my grandmother, who had the same name. So, I guess my mother could be called Eadie Jr., but instead they call her “Sweet,” or as my cousins say, “Ain’t Sweet.”

Every day when she rises, she washes her face, first with warm water, and then with cold water. Immediately after, she applies red lipstick. She then presses and rubs her thin lips together, while making smacking sounds to ensure she has them covered. Then, she puts a dab of red lipstick on each cheek and smooths the dot of color across her high cheekbones to make blush. She pulls out her pocket mirror, holds it up to her face to look at herself, lets out a little chuckle, and says, just above a whisper, “Umph, you a bad bitch. Look at God.”

My mother has always been a woman about town. As she has aged, her various illnesses have required her to use a wheelchair. This has not kept her from, in her words, “running the streets.” From rolling up on conversations at the corner spot or showing up for Sunday service at Union Springs Missionary Baptist Church to attending funerals for friends and catching public transportation to far-afield neighborhoods for bingo games, this woman harnesses little to no respect for fear.

These last few years have delivered significant health challenges and life changes to my mother’s doorstep. As a result, she has gone from enacting her lipstick ritual and using her electric wheelchair to traverse the city to needing around-the-clock care. This major shift has come under the cover of dementia and therefore is accompanied by bouts of stress, frustration, anger, joy, and unbridled happiness.

My mother and I speak every day. While our conversations are textured and detailed, for the most part they have become very repetitive, like the hook to a song we both know that is on constant rotation. As her condition evolves, I have noticed that, for her, time is elastic. I have learned that people with dementia can lose their sense of duration and their ability to comprehend how much time has passed. Because of this, she is often experiencing what is called time shifting, meaning that she is living at an earlier time in her life and she is talking to me as if I were there with her — only I may not have been there. This time shifting leads to disorientation and confusion, affecting how she understands the world around her.

For the last few months, our conversations have been mainly shaped by her short-term memories, but there are those watershed moments when she shares detailed accounts of experiences, real, reconstructed, or imagined. Those moments seem to have been buried deep in her personal archives. Sometimes her words are gentle and full of tender loving care, like when she says, “You know God gave you to me,” as if God walked up to her and handed her a beautifully wrapped gift box and I was inside. Then there are days when she is beside herself with anger, screaming with frustration for being misunderstood or for not being able to do what she is accustomed to doing.

I was recently rereading Audre Lorde’s “Eye to Eye: Black Women, Hatred and Anger.” She writes:

Every Black woman in America lives her life somewhere along a wide curve of ancient and unexpressed angers. My Black woman’s anger is a molten pond at the core of me, my most fiercely guarded secret. I know how much of my life as a wonderful feeling woman is laced through with this net of rage. It is an electric thread woven into every emotional tapestry upon which to set the essentials of my life — a boiling hot spring likely to erupt at any point, leaping out of my consciousness like a fire on the landscape. How to train that anger with accuracy rather than deny it has been one of the major tasks of my life.

When I revisited this text, I realized that my mother’s condition could be an effect of dementia or an outcome of her Black womanhood. In any case, Lorde helped me understand that I should not be dismissive of my mother’s narratives, but instead embrace and explore the potential accuracy with which she is telling her stories. It is in these moments of complete frustration, when I am witnessing my mother relive her life’s script, that I wish I had a gimlet to give her.

We recently packed up her apartment. In doing so, I paid attention to how she had covered the walls with images, items, and objects that are of interest or importance to her, including pictures of our family, her friends, Michael Jackson, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Reverend Ike, and President Barack Obama. There were awards, articles, and honors of mine from years past. There were plastic flowers, obituaries, Kama Sutra poses, knickknacks, and exercise instructions. When I stood back and looked at the walls, I realized her apartment was an installation.

It is in these moments of complete frustration, when I am witnessing my mother relive her life’s script, that I wish I had a gimlet to give her.

I felt like I was in her memories, in her hopes and aspirations. I was in her loophole of retreat. Those objects, these things are her gimlet. They are the tools that she used to bore holes through the opaque and inconsiderate slippage called dementia. Each of those objects that she brought to those walls allows her access to life as she once knew it, or how she hoped it would be. They are the holes that grant her access to air and light.

As someone whose work is about making museums meaningful, functional, and bound up in the everyday lives of people, I am moved by my mother’s deep and incisive understanding of how to make lives relevant through “things.” This is a powerful way to approach why we make things like objects and why we have museums in the first place.

My mother — my maker, Eadie Jackson, Sweet — recently experienced her 84th rotation around the sun. While celebrating, she told us stories, so I told her about Jacobs and the seven years she spent in her loophole of retreat.

She said, and I quote: “Seven years, what? She spent seven years in that tiny little space watching her kids play?”

I said, “Among other things, yes.”

And then she said, in the most complimentary way, “Umph . . . now that’s a bad bitch.”

To which I replied, “Do you think she wore red lipstick?”

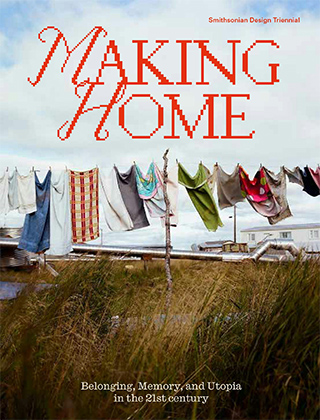

Sandra Jackson-Dumont is a curator, author, educator, administrator, and public advocate for reimagining the role of art museums in society. She served as director and CEO of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art from 2020 to 2025. This essay is excerpted from the collection “Making Home: Belonging, Memory, and Utopia in the 21st Century,” edited by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León, and Michelle Joan Wilkinson.

A version of this essay was first developed and presented at Simone Leigh’s Loophole of Retreat in Venice, Italy, October 8, 2022.