The Most Mournful Rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” Ever Performed

In what is arguably one of the greatest renditions of the national anthem performed before a live audience, Whitney Houston emerges on-screen and offers the Super Bowl crowd in Tampa, Florida, her distinctive voice for just under three minutes. The year is 1991, and the United States is 10 days into the Persian Gulf War. Race, sonic registers, and nationalism converge in this performance. It is unlike almost any other rendition then or since. And it has a referent.

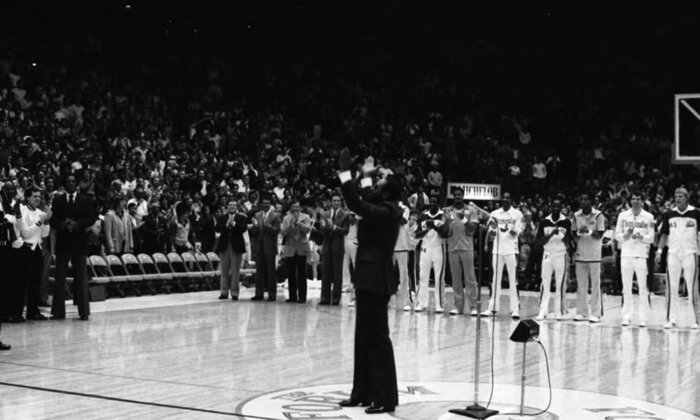

Houston said the only version of “The Star-Spangled Banner” she ever liked was Marvin Gaye’s 1983 performance at the NBA All-Star Game at the Forum in Los Angeles, California.

Dark blue suit and sunglasses — reflective — Gaye is accompanied by a drum beat and keyboard. The previous day’s rehearsal has many NBA executive types concerned. What does he think he is doing? “The mystery,” I. Augustus Durham writes of Marvin Gaye’s melancholic performances, “like the melody, still lingers on.” The performance is one part gospel rendition, one part improvisation, and all R&B swagger and style. It’s worth exploring what Houston found so compelling, so beautiful, that she used it as a guidepost for her own performance at the Super Bowl eight years later.

There is something bluesy in Gaye’s rendition that Houston is eager to recapture, a kind of sonic high and low that mourns even as it celebrates and glimmers with the possibility of freedom. This, I believe, is why Houston and Gaye both extend the note on the word “free,” signaling that this is work not yet done but work that must be done.

Amiri Baraka writes that “it is impossible to say how old the blues is,” and this atemporality haunts black musical performance. “It is native American music,” Baraka continues. “Blues could not exist if the African captives had not become American captives.” Is it possible, in the improvisatory space between an elongated captivity and a relatively short freedom, to represent a desire not yet fulfilled? Robert Hayden’s poem “Frederick Douglass” presents this conundrum of freedom as a temporal ellipsis, rather than a period.

When it is finally ours, this freedom, this liberty, this beautiful

and terrible thing, needful to man as air,

usable as earth; when it belongs at last to all,

when it is truly instinct, brain matter, diastole, systole,

reflex action; when it is finally won; when it is more

than the gaudy mumbo jumbo of politicians:

this man, this Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered. Oh, not with statues’ rhetoric,

not with legends and poems and wreaths of bronze alone,

but with the lives grown out of his life, the lives

fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.

With a repetition of “when,” and “this,” Hayden offers Douglass as a central figure of the nation in its pursuit of freedom and belonging. If there is no final destination for this “freedom,” then all that Douglass fought for, his successes and failures, belong to the nation as well. Because if freedom is “needful to man as air/usable as earth,” any refusal, national or cultural, is an investment in human erasure. It says the country traffics in images of inclusion that will never be fully incorporated, never real, and that this is the great irony of the United States. Its rhetoric of freedom is embedded in the reality of unfreedom.

What did Gaye know, when he sauntered, casually, to the stadium floor in his suit and aviator sunglasses, about what was to come?

What did Gaye know, when he sauntered, casually, to the stadium floor in his suit and aviator sunglasses, about what was to come? For him? For us? What did he sense in the moment, in the moments that followed, about redemption? Forgiveness. Mercy. Time. What did he carry on that day that we could and could not see? How can there be an elegy without clearly discernible loss?

Marvin Gaye’s stunning 1983 rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in Los Angeles was filled with the somber undertones of grief. In its purest R&B deliverance, Gaye’s version recuperates James Baldwin’s “ironic tenacity” of sonic release. To take the national anthem and loosen its war tones, replacing them with the singular voice of collective ecstasy, and all the while deceptively presenting the song as an upbeat groove meant to signal the collective vibration of those in need responding to the call that will get them home.

“I want to walk down the street under the new trees in Detroit, and tell Marvin I understand,” the poet Vievee Francis writes in her poem “Marvin Gaye: Sugar.” Francis continues, “To let his daddy go. / That—trouble don’t last unless you hold on to it. / But that’s not true. / Trouble is always. / He knew that. / You know that.” Francis marks Gaye’s spectacular emergence into the archive of musical exceptionality that he embodied. Stalked by demons and by death, the soft voice meeting the softer face collides into a temporal abyss that failed to measure the possibility of his brilliance without also claiming the right to subsume him entirely.

Marvin Gaye will die, murdered by his father a little over a year after his performance of the national anthem. His soulful plea during his NBA All-Star Game performance will follow him beyond death, and into the reservoir of meaning highlighted by his profound absence. Another one of Francis’s poems, “Marvin Gaye: Mercy,” trails the avenue of meaning left in the inscrutable act that precipitated his end — that the man to whom Gaye owed his life and his name (Gaye is named after his father) would be the one to take that life from him. Francis writes:

Take Marvin Gaye. His father had no mercy. Paranoia does that. Mercy is spat like spinach between the teeth. It slips out in a pee stream. Those without it lose it by adulthood. Flatline. It is replaced by a thin-lipped smile of rage. And with mercy goes empathy. But Marvin wanted mercy so badly from a man who didn’t have it to give, as if all he once had now rested in Marvin. Who wouldn’t be jealous? To see your better self. To hear all that beauty wafting out of every car window sweet as cigarette smoke. I don’t trust those who don’t like the smell. Orthodoxy. That was the gun in his daddy’s hand. It said don’t this and don’t that and the only goodness is to wither on your own vine. But how could a man in the flowering of his life, so much abundance, let it go? He needed. He lost. Lost to the one always praying who should have repented, whose sins (if there are sins) were all there to be seen as that bullet that set aside flesh. I imagine it differently. It soothes me to do so. Marvin spent in his father’s arms after a cruel night. Envy replaced by pride in the son. His own wintry pride displaced by . . . love. See, even you can’t stand such sentiment. So how much harder was it for Mr. Gaye on his high horse. Stomping down the seed.

From “His father had no mercy,” the speaker vessels through Gaye’s personal familial conundrum as the center of gravity in a house of patriarchal refusal. “Who wouldn’t be jealous?,” Francis writes. “To see your better self. To hear all that beauty wafting out of every car window sweet as cigarette smoke.” And just as quickly as smoke wafting up and out of a room with many windows, the residue of the scent remains. The speaker reimagines the death scene “differently” from the known account. “It soothes me to do so.” We are then offered an image of Gaye “spent in his father’s arms after a cruel night. Envy replaced by pride in the son.” If only a momentary reprieve, we take it. Because it allows for the temporary retrieval of this soft-voiced icon gone too soon and all too violently.

While Gaye may not have been making an explicit political statement, he nonetheless understood the power that the combination of his voice and the national anthem would have on his intended audience.

Marvin Gaye does something distinctive in this All-Star performance, so subtle and yet so very profound. You might miss it if you don’t listen to the song multiple times. Gaye’s musical performance takes Shana Redmond’s definition of black anthems as its centerpiece. She writes, “Music is a participatory enterprise that requires certain performative knowledges in order for its political and movement aims to be realized.” While Gaye may not have been making an explicit political statement by performing this song in this way, he nonetheless understood the power that the combination of his voice and the national anthem would have on his intended audience.

He was not wrong about this effect. I wonder, then, if attending to the visual apparatus of American flag imagery, while also listening to its sonic frequencies, can tell us something about the sight and the sound of a possible freedom, that which has yet to arrive?

If we consider the ubiquity of the American flag, its mandates and motifs, the way it signifies on itself as a measure of the U.S. nation-state, what might we uncover about blackness and its boundary markers? Gaye’s rendition alters the lyric “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave,” to the hauntingly possessive “O say does my star-spangled banner yet wave.” An intentional choice that references the way African Americans have existed on the margins of full citizenship.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” is not usually the favored anthem for black Americans. That honor goes to “America,” formally titled “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” The difference is minor but important. Instead of what is essentially a battle song of war (written by Francis Scott Key during the War of 1812), black Americans preferred the gentler patriotism of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” It is perhaps more easily assimilated into the history of African Americans, perhaps more poignant, less bold, but I would argue that the evolution of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” when black performers offer their talents to the song, is one way of envisioning the futurity of that which is beyond nation.

Kimberly Juanita Brown is the inaugural director of the Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life at Dartmouth College where she is also Associate Professor of English and creative writing. She is the author of, among other books, “Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual” and “Black Elegies: Meditations on the Art of Mourning,” from which this article is adapted.