The Media Hijinks of France’s Most Famous Unknown Artist

Fred Forest is fond of calling himself France’s “most famous unknown artist.” There is more than a grain of truth in this little bit of ironic bravado. By a number of measures, Forest should be a major figure in French contemporary art. After all, he is one of the pioneers and most inventive practitioners of video, telecommunication, and web art in France and an unparalleled master in the art of rogue interventions in the press and other mass media. Forest co-founded two noteworthy movements of the 1970s and 1980s, authored five provocative books in French on the social and epistemological relevance of art (or lack thereof) in today’s world, and has participated in major international exhibitions around the world.

Yet, despite these accomplishments, Forest has been largely ignored by the canon-making authorities of contemporary art in his home country throughout the better part of his career. He has never been represented by a major Paris gallery, has no work in the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou’s Musée National d’Art Moderne (MNAM), has never been promoted abroad by the French government as one of the stars of French art, unlike some of his more high-profile contemporaries, and his first retrospective in France did not take place until 2013, when a relatively small but well-designed exhibition called Fred Forest, homme-média no. 1 (Fred Forest, No. 1 Media Man) was held at the Centre des Arts in Enghien-les-Bains, outside Paris.

Nevertheless, Forest remains one of the living French artists most familiar to the general public in his home country. Indeed, his public notoriety and institutional neglect have at least one cause in common: Fred Forest is an incorrigible troublemaker with an uncanny knack for publicity. His penchant for making trouble has goaded certain political and institutional authorities into heavy-handed attempts to suppress his work (including arrests, police investigations, and lawsuits) and has alienated quite a few of the movers and shakers of the French contemporary art establishment — a favorite target of his over the years. Along the way, he’s garnered lots of media coverage and burnished his public persona as a fearless critic of the status quo, a genial prankster, and a visionary who takes art out of the white box and into the public arena of the street, the mass media, and the Internet. Imbued with his trademark over-the-top irony, Forest’s most notable acts of mischief stand out even in a field of contemporary art that is brimming with merry pranksters and agents provocateurs.

150 cm2 de papier journal (150 cm2 of Newspaper)

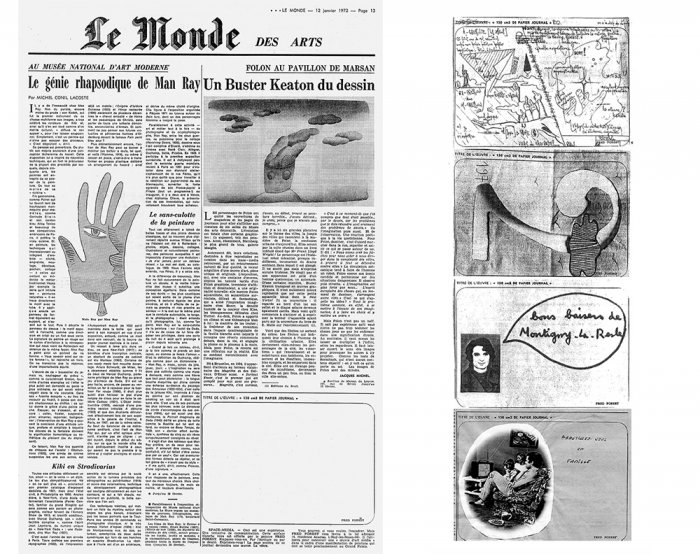

Forest gained his first measure of notoriety in 1972, when he inserted a small blank space in the pages of the prestigious Parisian daily Le Monde called “150 cm2 de papier journal.” Readers were asked to fill in the space with their own artwork, poetry, or commentary and to mail their contributions to Forest for inclusion in an exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris. On one level, this intervention can be seen as something of a practical joke. However, it was motivated by the serious utopian intention of creating a small opening for spontaneous feedback and creative self-expression in a closed system of communication, wherein the flow of information is ostensibly one-way — that is, from sources of power in the media, politics, capitalism, and art to the “masses.” Repeated in varied formats in publications across Europe and abroad over the course of several years as part of his Space-Media project, this emblematic action helped Forest win an early reputation as the man who “pokes holes in the media,” to quote the philosopher Vilém Flusser.

Le m2 artistique (The Artistic Square Meter)

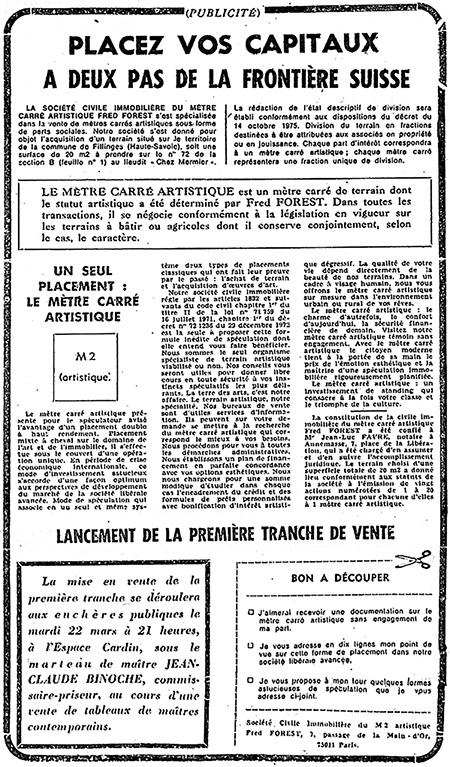

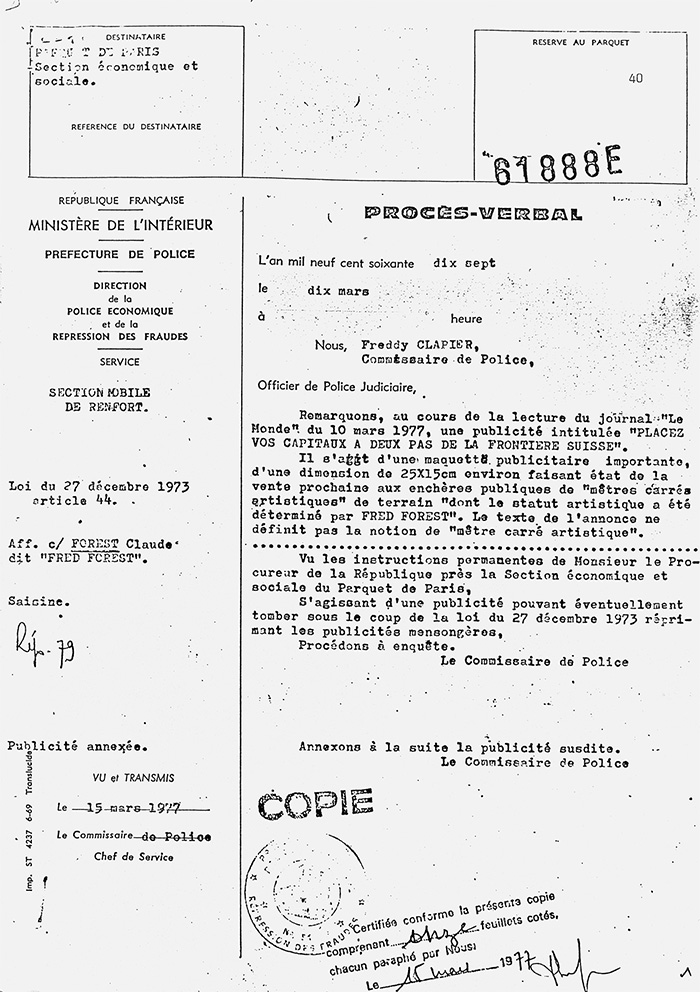

In 1977, Forest created one of the most highly publicized and arguably most potent works of his career when he staged a double parody of the shameless speculation common to the real estate and art markets: “Le m2 artistique” (The Artistic Square Meter). For this action, Forest formed his own real estate development company, through which he purchased a small tract of undeveloped land in the country, near the Swiss border. He subdivided the tract into one hundred tiny parcels, each measuring 1m2 in area, which he officially registered as “artistic square meters” at the local land office. With the complicity of contacts in the press, Forest then placed professional-looking advertisements in several prominent periodicals, announcing the upcoming sale of the first artistic square meter parcel at a public auction under the gavel of contemporary art specialist Jean-Claude Binoche.

Like so many other Forest projects, this intervention thrived on the ambiguity of its status. On the one hand, there was the nominal reference to art — the source of a certain form of legitimacy that Forest leveraged to his benefit (e.g., to obtain free advertising space from sympathetic art-loving contacts in the press) — even though there was yet again only blank space where one might normally expect to find an actual, content-bearing, finished work of some sort. The project’s artistic status was further validated by the initial lot’s inclusion alongside works for sale by recognized figures like Claude Chaissac, Erró, Simon Hantaï, Nikki de Saint-Phalle, Nicolas de Staël, and Victor Vaserely in the bound catalog that was prepared for the announced auction. On the other hand, the project was conspicuously launched in a non-artistic venue (the business pages of a newspaper) and made a point of seeking sources of legitimacy outside the art world—namely, in the real estate market and the press. It simultaneously targeted different audiences (art aficionados, real estate investors, curious newspaper readers), in which it hoped to set off a series of questions. Was it art or a parody of art? Real news or a publicity stunt? A legitimate business venture or a scam?

Given this calculated ambiguity, the project also raised serious questions in the minds of the authorities. The ads aroused the suspicion of both the police fraud division and the syndicate of French notaries, who lodged a formal complaint over the art auctioneer’s alleged infringement on the notaries’ exclusive right to handle real estate transactions. Under suspicion of false advertising (what could be “artistic” about a tiny parcel of undeveloped land in the country?) and the intent to commit real estate fraud, Forest became the subject of a formal police investigation that included a lengthy (and often hilarious) interrogation at police headquarters and the dispatching of gendarmes to inspect the property. Ultimately, the prosecutor’s office issued an injunction prohibiting the sale.

Undeterred by such legal obstacles, Forest instead auctioned off a substitute item, which he took great care to officially bill as “nonartistic”: a square meter of common fabric purchased on the morning of the auction from a neighborhood merchant and trod upon by the people arriving at the auction. This fabric sample cost Forest a mere 59 francs (ten U.S. dollars) but fetched a sale price of 6,500 francs ($1,200) at the auction. In a statement contradicting Forest’s own disclaimer about the nature of the object sold, the renowned art critic and founder of Nouveau Réalisme, Pierre Restany, publicly affirmed the artistic status of the square meter — that is, the substitute item, the original parcel of land, the underlying concept, and the entire operation that had taken place including its legal and media ramifications — at an impromptu press conference held at the conclusion of the auction.

However, Restany’s expert opinion was just a pro forma confirmation of a de facto reality, for it was, as usual, a combination of publicity, art world ritual, and the inflated market value set at auction that formed the real basis for the artistic status of both the actual item sold and the broader project — precisely the point that Forest was trying to make in the first place. Hence, Forest might have lost his legal battle, but he won his artistic wager by parlaying the predictable overreaction of the authorities to something that didn’t fit neatly into the established categories of either real estate or art into lots of publicity, thereby offering an ironic demonstration of the role the latter plays in driving up the market value of art.

L’œuvre perdue (The Lost Work)

Forest touched off another outlandish legal battle over the definition and value of art in 1982 when he discovered that employees of the Musée des Beaux Arts in Lausanne, Switzerland, had accidentally thrown out documents that were part of one of his press projects during routine housekeeping. The project, exhibited in 1978, was “La maison de vos rêves” (The Home of Your Dreams), and the discarded documents in question included hundreds of responses to an invitation to readers published in the Lausanne newspaper in the form of a blank square, similar to the one used for “150 cm2 of Newspaper,” asking them to send in depictions of their idea of a dream house.

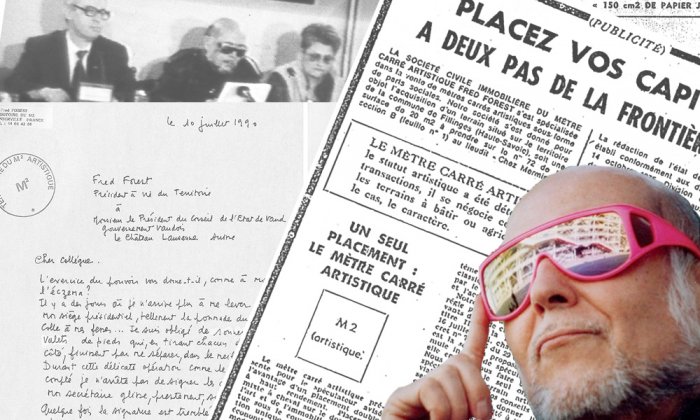

When government officials rescinded a museum offer to compensate Forest for the lost materials on the grounds that neither their artistic status nor Forest’s ownership of them could be firmly established, Forest sued. Following a protracted series of hearings, not only was the Canton of Vaud’s refusal to compensate Forest for his loss validated at the appellate level, but the artist was ordered to pay damages to the Swiss authorities. Forest’s response, in 1990, was to “declare war” on Switzerland — a war waged in the form of a tongue-in-cheek but nonetheless harassing letter-writing campaign targeting a range of public officials and other parties: the president of the state council of Vaud (sent a daily letter over the course of four months); the regional military command, asked to commit resources to a search for the lost items; the local mental health service, asked to treat Forest for the depression caused by his traumatic loss; a manufacturer of organs, asked to donate instruments for a ceremony commemorating the disappearance; and a maker of monuments, asked to create a memorial stele honoring his dearly departed work of art, to be erected in front of the museum in Lausanne. Forest’s brilliant epistolary action/social sculpture, which he called “L’œuvre perdue” (The Lost Work), undertaken in his official capacity as president of the independent Territory of the Square Meter, cheekily tested the limits of his correspondents’ patience, professionalism, and deference to the public to great comic effect and elicited more media attention and discussion than the original press work in question.

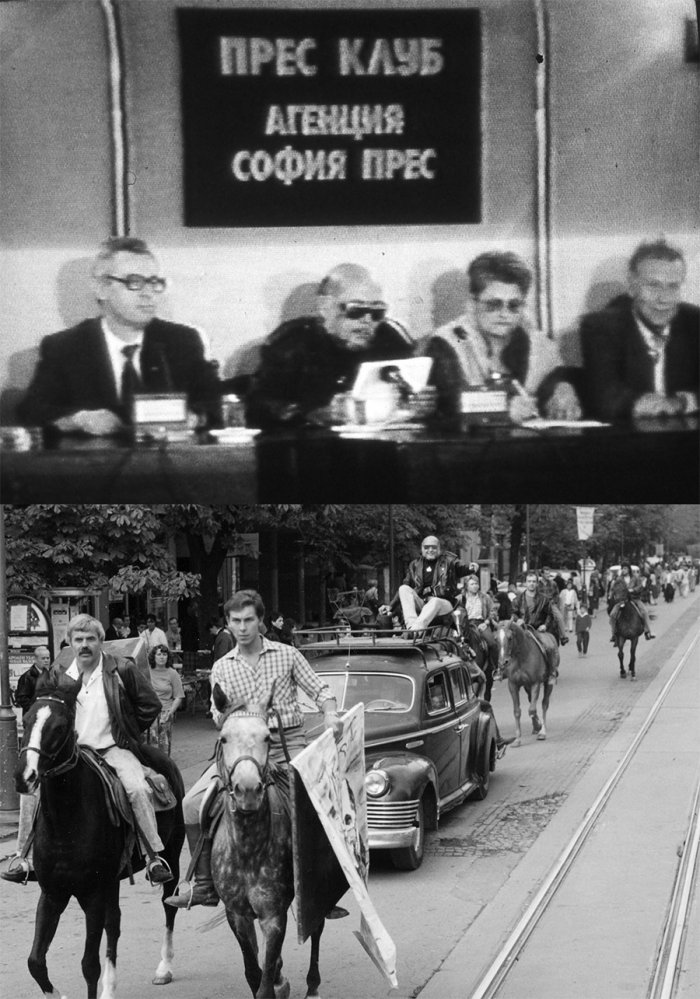

Fred Forest’s campaign for the president of Bulgarian TV

Whereas Swiss authorities might have seen Forest primarily as a nuisance, Bulgarian officials took him more seriously as a threat when in 1991 he donned a pair of fluorescent pink sunglasses and headed for Sofia. There, he waged a surreal public campaign for the presidency of Bulgarian national television, which he promised to make more “utopian and nervous.” With the complicity of a handful of Bulgarian opposition intellectuals and journalists, Forest leveraged his romantic aura as a French artist and the intellectual prestige of his position as a professor at the Sorbonne to gain credibility in the eyes of the local media and public.

The highlight of Forest’s brief stay in the Bulgarian capital was a farcical motorcade through the streets of the city center featuring escorts on horseback bearing gutted television sets and rabbit-ear antennae, a vintage ZIL limousine once used by the former Communist head of state, and Forest wearing his fluorescent pink sunglasses.

Coming weeks before critical parliamentary elections, the unsolicited candidacy of the foreign interloper did not sit well with the rulers of the Balkan nation, which was then still slowly emerging from decades of Stalinism. Surprisingly, however, the sitting president of the Bulgarian broadcasting authority, Oleg Saparev, accepted Forest’s challenge to participate in a televised debate — out of an apparent desire to display his democratic good faith — before quickly reversing course and backing out. The highlight of Forest’s brief stay in the Bulgarian capital was a farcical motorcade through the streets of the city center featuring escorts on horseback bearing gutted television sets and rabbit-ear antennae, a vintage ZIL limousine once used by the former Communist head of state, and Forest wearing his fluorescent pink sunglasses.

Although he had planned to stay in the country longer and even go on a campaign tour in the provinces, Forest hastily left the country soon after the motorcade and a final press conference, having been told that his personal safety in Bulgaria could no longer be guaranteed. As he tells it, Forest performed like a judoka throughout the operation, leveraging the power of the media and using his adversaries’ cumbersome size and characteristically bureaucratic inability to react quickly and decisively against him to gain a brief tactical advantage just long enough to make his point. This is particularly true of Forest’s painfully funny war of nerves with Saparev, who fell into his trap and then backed out when it was too late, having already given Forest far more prestige than he deserved and making himself look ridiculous and cowardly in the process.

In Forest’s best work, he operates in public venues that are conspicuously not artsy, intellectual, and elitist; he turns the controls over to average users, making them responsible for the meaning (or nonsense) conveyed through the hijacked system. Derrick de Kerckhove, an important collaborator of Forest’s in the 1980s, described Forest’s approach as “the inverse of terrorism.” By this, de Kerckhove meant that Forest, like a terrorist, uses information as weapon, counting on the media to amplify the destabilizing effect of sensational events in public space that seem to occur out of nowhere, taking people by surprise and grabbing their heightened attention for a brief time. He uses the predictable overreaction of authorities, an expression of their paranoia and embarrassment, as the second step in a chain reaction of escalating events that he can further exploit. However, unlike a terrorist, Forest causes no real damage, and his intent is not to tear the community apart by mobilizing its basest instincts (fear, the scapegoat mechanism, bigotry, repression, etc.) but to make it stronger by mobilizing its creative energies in a positive way.

Forest’s vision of art is utopian in this way. He is not just a prankster and a hijacker, but also a trespasser and a poacher, two metaphors used by Michel de Certeau, whose writings about popular culture, urban space, and everyday life influenced Forest. For Certeau, the transgressions of the trespasser and the poacher were paradigms for the artful tactics used all the time by ordinary people to fleetingly reclaim the spaces, products, and messages of the dominant culture. These spaces and the objects they contain are rigidly ordered according to the strategic prerogatives, special interests, and ideological a priori of the powerful, as if they were restricted preserves. Instead of overturning the existing order, which is a highly improbable outcome, ordinary people resist more modestly (and furtively) on an everyday basis by cutting corners, tinkering with the things with which they are forced to make do, and dreaming against the grain. This is what Forest does — and asks others to do — when he invites them to join him in trespassing in media space.

Michael Leruth is professor of French & Francophone studies at the College of William and Mary and the author of “Fred Forest’s Utopia: Media Art and Activism,” from which this article is adapted.