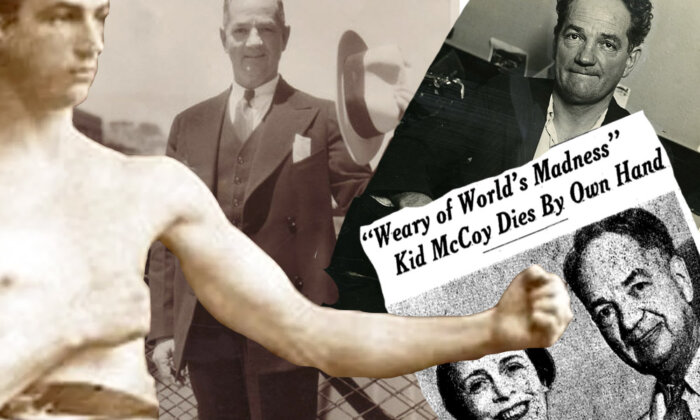

The Many Lives of Norman Selby, the “Real McCoy”

The more adroit we are at carbon copies, the more confused we are about the unique, the original, the Real McCoy.

We don’t even know who the Real McCoy was. Some say it was Elijah McCoy, born in 1843 within a community of African Americans who had escaped to Canada from slavery in the South. Taking ship to Scotland, McCoy apprenticed to a mechanical engineer. Upon his return across the Atlantic, the job he found with the Michigan Central Railroad was as a fireman, stoking the engine, but between 1872 and 1882 he was awarded patents on an automatic engine lubricating device of such reliability that it was known to the industry as “The Real McCoy.” He became a patent consultant to the railroads and moved to Detroit, where after a long life he died alone and penniless in an infirmary in 1929.

Some say it was Bill McCoy, a sailor “with the heart of a mischievous, authority-scorning, rather gallant small boy.” Six-foot-two, he was the Robin Hood of the Bahamas between 1919 and 1924, carrying 175,000 cases of rum across the Caribbean in the hold of his schooner, then selling the liquor on the high seas to rumrunners who smuggled it into Prohibition America, where it would be watered down four-to-one. “His erstwhile associates,” wrote a friend in 1931, “have epitomized his square crookedness in a phrase that has become a part of the nation’s slang: ‘The Real McCoy’ — signifying all that is best and most genuine.”

Still others say the Real McCoy was an American born in 1873 in Moscow, Indiana, and known as Kid McCoy, whose life and death would take in nearly every theme of this book [“The Culture of the Copy].”

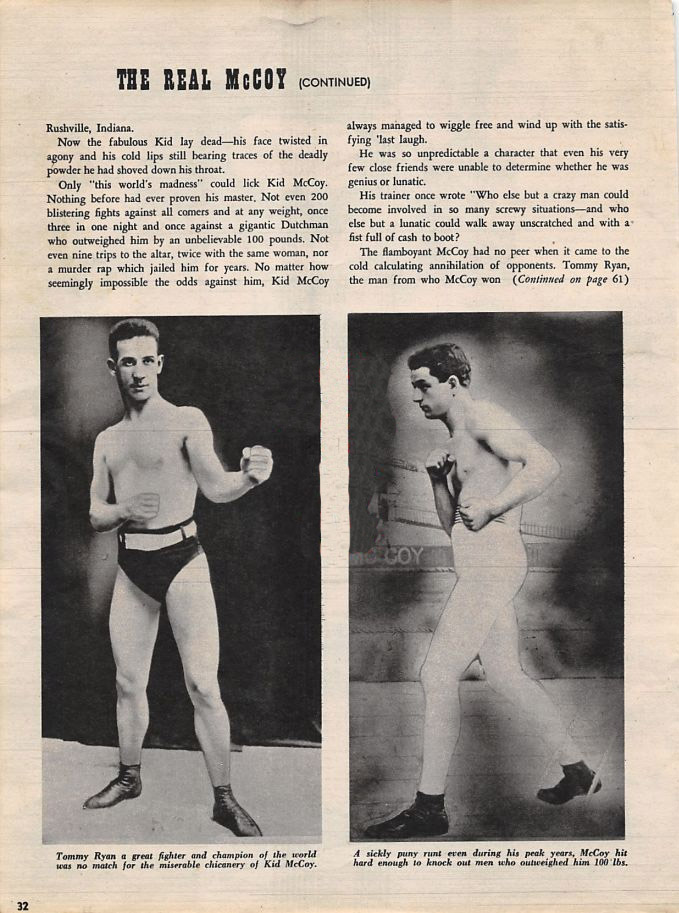

“Kid” was a moniker for gunslingers and boxers. As a boxer, Norman Selby won his first professional bout in Butte, Montana, at the age of seventeen. The next year, 1891, he became Charles McCoy, assuming a surname of renown in his part of Indiana. Throughout the 1890s, McCoy entered the ring about once a month, as a lightweight, a welterweight, then a middleweight, winning with footwork, guile, and a trademark left hook. Fast, strong, 5 feet 10 and three-quarter inches, with an astonishing reach (said the sporting pages) of 76 inches, he would practice for hours jumping sideways and running backwards — for his time, perhaps, “the fastest backward runner in the world.” He won all but six of his 105 recorded bouts and many others, unrecorded or pseudonymous. He thought of himself, like Jim Corbett, as a “scientific fighter.”

Theatrical would be a better word. Corbett himself trod the boards in such melodramas as “Honest Hearts and Willing Hands,” simulating prize fights, and McCoy appeared in “The Pacific Mail.” As underpaid sparring partner to welterweight champion Tommy Ryan, the Kid was rumored to have conned Ryan into thinking that their match in March 1896 was just an exhibition or that he would be a pushover, so the champ entered the ring unprepared for serious fisticuffs. During the intros, Ryan slapped McCoy on the back and yelled to the crowd, “All he knows, I taught him.” But Ryan at 145 and out of training was no match for the crafty Kid at 158 with his backwards running. He was at the Kid’s mercy for much of the fight until KO’d in the 15th.

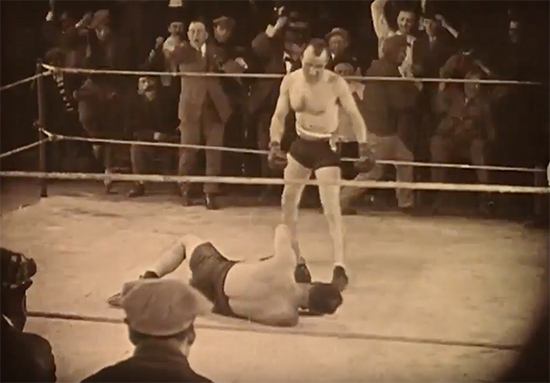

Weeks later McCoy went down at the feet of Joe Choynski, but a timekeeper rang the bell 40 seconds early; McCoy wound up victorious by throwing a punch after the bell of the last round, to cries of “Fraud! Fake! Robbery! Foul!” He divorced his first and obscure wife, an Ohio shop girl, to marry and shortly divorce a more obscure second wife, to court the suffrage lecturer and light-comic actress Julia Woodruff. Acting out a comedy of their own, Julia and the Kid would marry and divorce three times over the next seven years. Along the way, McCoy became as legendary for his wiles as for his “corkscrew” punch, fighting under pseudonyms in the United States, South Africa, and Europe. The Kid, wrote sportswriter Damon Runyon, was “One of the cleverest, craftiest men who ever put on boxing gloves.” With his winnings he bought the bar at Broadway’s Casino Theatre, where men and women alike came to be seen at century’s turn, and where McCoy became a gentleman. The Broadway Magazine suggested that “His manners might well be copied by other prominent men of the ring” — some of the lesser of whom had already been copping his name and reputation. When the Kid met Choynski again in San Francisco in 1899, he was knocked down 16 times but KO’d Choynski in the 20th. The headlines read, “NOW YOU’VE SEEN THE REAL McCOY.”

Had they? Julia accused her on-again off-again husband of “faking” in the ring, of pretending to be on the verge of collapse so as to throw opponents off guard. On August 30th, 1900, at Madison Square Garden, gentleman Kid McCoy, “the shiftiest man in the ring, blocking or evading the fiercest blow in the fistic art,” battled Gentleman Jim Corbett, recently accused of colluding with Tom Sharkey in a match “rehearsed blow for blow.” The hype was hot — it was the Kid’s shot at the heavyweight crown. The New York World newspaper showed McCoy filling out to 168 pounds, swimming and diving, “Bigger and Stronger Than Ever.” During round five, however, the Kid dropped to the mat “and gave an excellent imitation of a man in distress.” Nowhere in evidence had been his corkscrew punch, “an inward twisting of the fist for a distance of six inches or less that shatters bone where it lands and benumbs its victims.” McCoy, it seemed, had taken a dive.

Corbett’s wife told a reporter, “The fight was a fake, and every sporting man in town knows. . . . McCoy did not train, knowing Corbett was to lie down. Half an hour before the fight Corbett refused to lie down and gave the ‘Kid’ the double cross. McCoy was so mad that he would not shake hands.” It was true that McCoy had neglected the conventional bumping of gloves, but he denied the rest. “I fought a bad and a wrong kind of fight,” he explained, “by smothering up and not being the aggressor.” He was unhurt until he “received the hard punch in the stomach, a spot where it does not take a very hard punch to incapacitate one from being able to fight for the few seconds allowed to recover.” Corbett’s wife changed her story: The fight had not been fixed, but she was about to divorce Gentleman Jim and had wanted to get even with him for his infidelities.

Julia, embarrassed by the scandal, sued the Kid for divorce, then thought better of it. They went arm in arm to his health farm near Saratoga, where Julia met a Yale coxswain, with whom she rowed off to Japan. The Kid, a man of fortitude and rodomontade, got hitched in 1903 to actress Indianola Arnold, Dorothy in the stage hit, “The Wizard of Oz;” the Kid also got hitched, as it were, to Lionel Barrymore, an admirer studying McCoy for the part of Kid Garvey in the “The Pug and the Parson,” retitled for propriety’s sake “The Other Girl,” that girl being an heiress Garvey aims to wed. The playwright, Augustus Thomas, could see the resemblance between Barrymore and McCoy from half a block away; it was easy to mistake the one for the other, he wrote, as they chummed the Broadway waters. Barrymore’s success with the part was no less pronounced in 1903–04 than was McCoy’s identification with the play, which he attended nightly to see himself reenacted.

Bankrupt in 1904, the Kid in 1905 married an heiress. By 1906, as Norman Selby, he was head of a firm of diamond dealers and, possibly, smugglers.

Bankrupt in 1904, the Kid in 1905 married an heiress. By 1906, as Norman Selby, he was head of a firm of diamond dealers and, possibly, smugglers. In 1907, he superintended the National Detective Agency. For this, he quickly admitted, he was ill-suited: Although he had read Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe, he found, he told the New Jersey Telegraph, that “Try as I will I cannot detect.” He sold and raced automobiles, was caught speeding. He “dug up a load of ancestors to fill out the bare branches of his family tree” and break into high society, according to the Telegraph, or to make claims upon the $200,000,000 estate of Lord Hume of London, to whom he was “closely related.” He clumsily defeated a novice boxer in 1908, as reported by Vanity Fair, though “sans punch, sans ‘corkscrew,’ sans sneer, sans strength, sans speed, sans science, sans everything that goes to make a boxer.” He invested in rathskellers, traded in jewelry, lost his shirt, and again declared bankruptcy; among his creditors was the Manhattan Press Clipping Bureau, which had kept track of every failure, for he was nothing if not a public man. He sailed to Europe, joked and sparred with Belgian poet Maurice Maeterlinck, then settled in London to run “a physical regeneration establishment” at a fashionable hotel. There too, wrote a reporter at the Washington Star in 1912, “one feels that [McCoy] is constantly posing. At the present time a ten-minute talk with the ex-pugilist is sure to include a little ‘new thought,’ a mixed philosophy culled from a more-or-less complete reading of Hegel, Kant, and Nietzsche, and a sprinkling of his own unique personality.” He was arrested as a jewel smuggler — mistaken identity, apologized the British police. “I am very pleased to be exonerated,” said McCoy. “I never was dishonest in my life.”

“One feels that [McCoy] is constantly posing. At the present time a ten-minute talk with the ex-pugilist is sure to include a little ‘new thought,’ a mixed philosophy culled from a more-or-less complete reading of Hegel, Kant, and Nietzsche, and a sprinkling of his own unique personality.”

1913 and he was back in the States, running an “Auto Bluff” and advising the Chicago News, “Get your bluff in first. That’s a rule of life that applies to motoring as well as to fighting.” 1914 and he was in Los Angeles tending a health farm, which failed despite his philosophy that “Nature’s universal law is: GROW OR GO!” 1916 and he was roving New York again, staging fist-fights for the National Guard and divorcing a fifth — or was it a sixth? — wife. “How can you promise to love a woman all your life?” he asked. “You change; the whole world changes,” he told the Columbus Journal. 1918 and Sergeant Selby of the 71st New York Infantry was discharged on account of his age, about which he had lied. He was 44 and eager for a new career. In film.

Selby had experience: He had collaborated with Corbett in a movie simulation of their infamous bout (they had to send for a newspaper to find out what each of them had done in the fight). Now he would simulate his own life on both sides of the law, playing a cool detective investigating a jewel heist in “The House of Glass.” In 1919, he appeared in D. W. Griffith’s masterpiece, “Broken Blossoms: Or, The Yellow Man and the Girl,” with Richard Barthelmess and Lillian Gish, whose father (in the film) is Battling Burrows, “a gorilla of the jungles of East London,” a brutal prizefighter who KO’s the Kid and beats Gish to death. By 1920 McCoy was living in Hollywood and running with art dealer and gem smuggler Albert Mors. On screen the Kid seconded Buck Jones in what Variety called a “daredevil picture,” “To a Finish” (1921), and burlesqued a gumshoe in “Oathbound” (1922), an undistinguished film “for the cheaper daily change houses.”

His starring role came in 1924. While making his bucks as a gun-toting bodyguard to a shady promoter, he was making his bed as Mr. Shields to the Mrs. Shields of Theresa Mors, divorced from Albert, who called her “a curious mixture of saint and sinner.” Selby called her suicidal; she was mopey after the Feds, going after Albert & Co., seized the ice in her safe deposit boxes as Austrian contraband. On the witness stand in December, before a capacity crowd, Selby sat very still, “like a manikin perched on a ventriloquist’s knee,” according to the New York Times. Then he began to rehearse, gesture by silent-screen gesture, the sad evening of 12 August past. He and Theresa, or Tess, had been in their apartment, drinking Scotch & soda out of a silver loving cup. He made sandwiches. Tess asked him to cut hers into morsels, which he did with a kitchen knife that she abruptly took up, to plunge into her bosom. He struggled with her, wresting the knife away. Somehow she got hold of his pistol. Another struggle. (Here Selby wrestled himself, “stepping about with the agility of a younger Kid McCoy in the throes of a scene of shadow-boxing.”) The gun went off. For a moment he did not know which of them had been shot. When that was obvious, he decided to end it all. He rested Tess on the floor, nestled a photograph of himself in her arms, and lay down beside her.

The jury deliberated for 78 hours before finding the most widely married man in America, the “victor of a hundred prize-ring battles and breaker of a thousand hearts,” guilty of (wo)manslaughter.

Why he didn’t shoot himself, he couldn’t say. He did rise, take a stiff drink, and drive around looking in vain for Albert. Thence to his sister Jennie’s to tell her that Tess was dead and he had nothing more to live for. Next morning, to Mors’s antique shop, intent on revenge. Mors was out, and Selby a little out of his mind. He held at gunpoint the shop manager, the secretary, and several customers, shouting a silent-screen caption, “Nobody ever loved anyone like I loved Tess. I’d go to the electric chair for her.” He asked lawyer Lewis Jones, caught in the act of browsing, to defend him once he bumped off Mors, telling Jones, “Stick around, kid. You’ll see more fun here than you have ever seen in a courtroom in your life.” He stuffed money into the suit of a customer who confessed to carrying no cash, had two other men strip to their shorts, and shot at a fourth who tried to escape. He ordered the porter to “Strike up some music on the phonograph,” according to the San Diego Union, “so these people can pass out to slow music.”

Instead, Mors a no-show, Selby ran to his Ford, sped to the millinery shop owned by Mors’s friends Sam and Anna Schapps (who had called Selby a “love pirate”) and shot them both. Was he mad or remorseful enough to go finally to the nearest cop and hand him the gun — or, as the police swore, was he caught at the scene? The prosecution said that he was angry at having been excluded from the management of Tess’s estate (worth $110,000) — and angry at Albert, who in a letter to Selby’s brother-in-law had threatened Selby, calling him “a moral leper.” The D.A. demonstrated that Theresa had been shot from behind, in cold blood, but he never had Albert testify, and the defense hinted that Mors had been seen running from the scene late that August night. The jury deliberated for 78 hours before finding the most widely married man in America, the “victor of a hundred prize-ring battles and breaker of a thousand hearts,” guilty of (wo)manslaughter. In February there was a second trial, this for assault with a deadly weapon in the three woundings. Convicted, Selby was sentenced to 3–38 years at San Quentin.

A model prisoner, he raised canaries and taught newcomers the ropes. When he was paroled in 1933, Henry Ford appointed Selby director of the guards for the 12,000 company thrift gardens. Off work, he spoke to church groups on the postural and dietary causes of juvenile delinquency and had occasion to save some children from drowning. In 1937, with a full pardon for the murder of Theresa Mors, he pondered a vaudeville tour, then married for a ninth (actually, a 10th) time and lived with his new wife (her fourth marriage) in Detroit. There Norman grew agitated at the news from Europe and depressed about his own efforts to uplift youngsters, which were not going well despite his own use of health suspenders. In April 1940, Nazi troops racing across Denmark, he said he had to go to Chicago on business. He checked into a Detroit hotel, scribbled three suicide notes, and swallowed sleeping pills. One note read, “For the past eight years I have wanted to help humanity, especially the youngsters, who do not know Nature’s laws.” A second, “To all my friends I wish you the best of luck.” The third, perhaps the Real McCoy: “I can no longer endure this world’s madness.”

“He had been a convict, social lion, saloon porter, hero of a short story classic, dishwasher, owner of a New York jewelry store and night club, a bankrupt, film actor, auto racer, confidante of Maurice Maeterlinck and, in recent years, a Ford employee.”

“It had been a daffy world for McCoy,” said Variety in its obit. “He had been a convict, social lion, saloon porter, hero of a short story classic, dishwasher, owner of a New York jewelry store and night club, a bankrupt, film actor, auto racer, confidante of Maurice Maeterlinck and, in recent years, a Ford employee.” It was paradigmatic of his life, and of the fate of Real McCoys this century, that during his second trial, being shuttled from court to county jail, Selby should meet a fan, throw one arm around him, and shake hands warmly, although Charlie Chaplin was in the halls of justice not to wish the Kid luck but to sue an impersonator who had stolen his costume and character. How determinedly had Chaplin fashioned the costume and character? asked the Court. Very determinedly, testified Chaplin, with regard to the costume, but as to the character, “I’m unconscious while I’m acting. I live the role and I am not myself.”

Norman Selby, who lived in the shadow of a Kid, perpetually failed to be himself. That was the reason, he said, for his divorces: “All but one of my wives married Kid McCoy,” he told the Columbus Journal. “The other [the first, Lottie Piehler] married Norman Selby.” His pseudonym overtook the original and became eponymous, which is the way of things, and of people, in our culture of the copy. We admire the unique, then we reproduce it: faithfully, fatuously, faithlessly, fortuitously. Who and which and where may be the Real McCoy, those are uneasy questions. With fancy footwork we may fight rearguard actions to hold the natural at arm’s length from the artificial and keep the one-of-a-kind out of the clinch of the facsimile, but the world we inhabit is close with multiples.

Hillel Schwartz is an American cultural historian, poet, and translator. He is the author of several books, including “Long Days, Last Days,” “Making Noise,” and “The Culture of the Copy,” from which this article is excerpted.