The Joys and Sorrows of the Matthew Effect

Timing is everything. In 1996, a committee of British experts turned down the funding request of their colleague Harold Kroto. Two hours later, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced the Nobel Prize for chemistry would go to Robert Curl Jr., Richard Smalley, and Harold Kroto “for changing the way we think in physics and chemistry with their discovery of fullerenes.” The British committee had to backtrack and reverse its decision by giving Kroto the money. Thanks to the recognition from Stockholm, the British chemist was admitted into the exclusive circle of so-called visible scientists: elite researchers whose public recognition accords them almost bulletproof prestige and a reputation that can open just about any door.

The founder of the sociology of sciences, Robert K. Merton, understood this phenomenon and its cumulative effect. He called it the “Matthew effect,” from the Gospel passage that says “For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance; but from him that hath not, shall be taken away even that which he hath.” (Matthew 25:29):

Those who already have visibility and prestige will have privileged access to other resources and opportunities for visibility, and so on

[…] a scientific contribution will have greater visibility in the community of scientists when it is introduced by a scientist of high mark than when it is introduced by a scientist who has not yet made his mark.

In the words of a Nobel laureate in physics, “the world tends to give credit to [already] famous people.”

Analyzing some empirical data, Merton and his students discovered that essays submitted to a scientific journal were more frequently accepted if a Nobel laureate or a particularly well-known researcher were among their authors. Similarly, essays from a scientist were more often cited by their colleagues after they had been awarded a widely known prize such as the Nobel.

As a paradigmatic case, Merton recalls the story of Lord Rayleigh, Nobel laureate for physics in 1904. His name had been accidentally omitted from a manuscript presented to the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The committee turned it down, thinking it was “the work of one of those curious persons called paradoxers.” As soon as the real author was discovered, the manuscript was accepted. Merton considered these mechanisms to be due to the poor “recognition” capacity in science and the rigidity of its allocation system. In the illustrious Académie Française, where only 40 places were available, the “forty-first chair” included the likes of René Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Stendhal, Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola, and Marcel Proust.

Merton considered the Matthew effect to be “dysfunctional for the careers of single scientists, who are penalized during the initial stages of their activity,” but functional for science in general, winnowing the huge quantity of results, publications, and other projects. Furthermore, the names of famous scientists were able to attract the community’s attention to particularly innovative discoveries that would otherwise have struggled to be taken into consideration.

It is difficult — extremely difficult — to become a celebrity scientist. But once acquired, celebrity feeds on itself. To quote Merton: “Once a Nobel laureate, always a Nobel laureate.” Thus, the Nobel Prize is often a prelude to further recognition and benefits.

Einstein summarized his experience with his usual irony: “As punishment for my contempt for authority, destiny has made me an authority.”

The physicist Robert Millikan received 20 honorary university degrees and 16 significant prizes after he was awarded a Nobel; the chemist Harold Urey calculated the financial benefits deriving from his Nobel as “four to five times the sum received for the Prize.” Many British laureates were later offered the title of baronet and commemorated on stamps. Three Italian laureates were nominated as senators for life: Guglielmo Marconi, Rita Levi-Montalcini, and Carlo Rubbia. According to Kary Mullis, Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1993, the prize is a sort of “universal access key”:

Nobody in the world doesn’t understand the weight of the Nobel Prize. Once you have it, there is not a single office in the world that you can’t go into. If I call them and say, I would like to talk to you about something, and I’m so-and-so, the Nobel laureate, they’ll see me at least once. It opens every door.

Hiroshi Amano received approximately 400 requests for conferences per year. After he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 2014 for the invention of light-emitting diodes (LED), the number of invitations increased by 1,000 percent. The Nobel, he claimed, gave him the opportunity to explain the importance of his research for environmental protection and to accelerate its industrial applications.

Some Nobel laureates have tried turning their notoriety to political ends. On January 14, 1992, 104 laureates signed a public appeal for peace in Croatia published by the New York Times. When Salvatore Luria (Nobel Prize for medicine 1969) received a telegram of congratulations from President Richard Nixon, he immediately replied with another telegram asking the president to end the American intervention in Vietnam.

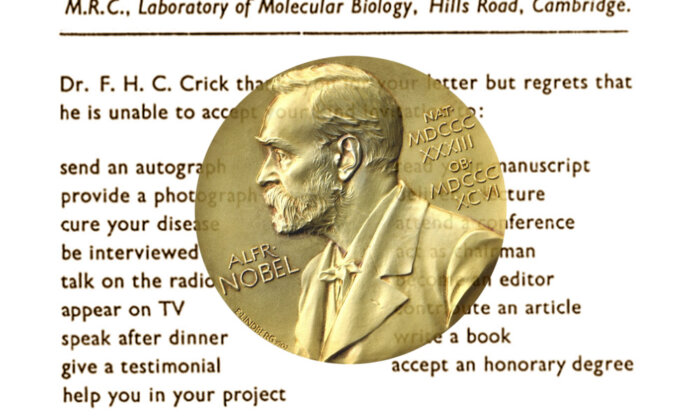

Often Nobel recipients have suffered from their own popularity. “We are swamped by letters and visits from photographers and journalists,” complained Marie Curie in 1903 after her first Nobel for physics (she would be one of the very few to receive a second one, for chemistry). Francis Crick (medicine, 1962, with James Watson, for the discovery of the structure of DNA) drafted a standard form to apologize for being “unable to accept your kind invitation to …” with check boxes for “… deliver a lecture … cure your disease … be interviewed … appear on TV … write a book … accept an honorary degree …”

Einstein summarized his experience with his usual irony: “As punishment for my contempt for authority, destiny has made me an authority.”

Massimiano Bucchi is Professor of Science and Technology in Society at the University of Trento and former editor of Public Understanding of Science. His most recent books include “Newton’s Chicken” and “Geniuses, Heroes, and Saints,” from which this article is excerpted.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Kary Mullis’s Nobel Prize. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, not Physics.