The Hacker Folk Art of Esoteric Coding

I first decided to make my own language when I read an academic paper on the game Minesweeper.

In the signature computer solitaire game of the 1990s, you click on tiles, one at a time, revealing a mine — if you are unlucky — or a safe tile indicating how many mines are nearby. The paper proved that an accidental simulation of a computer lurked in the mechanics of the game, written in the partial knowledge of where mines might be. As each mine is revealed, the locations of others resolve, creating flows through the physical space of the board. These flows combine to simulate logic gates and ultimately perform computation. No one needed this system to exist, it had no purpose, and yet it could represent any algorithm written in the eagerly utilitarian languages of Python or C#.

Commercial and academic languages, each in their own way, aim to minimize the cognitive work needed to understand code’s performance. But this accidental computer showed a radically different path: what a pure code anti-style might look like. It felt like a challenge to see how far one could push the concept of code, reconsider what it is for, what form it can take, and what questions it can ask. Designing a language that similarly broke from computational norms seemed the best way to explore these questions.

I was not the only one interested in the peripheries of language design. A rich hacker culture of esolangs had begun in the early 1990s. The parody language INTERCAL was revived as C-INTERCAL, where one literally pleads with the interpreter to run their cryptic code. The minimalist languages FALSE, brainfuck, and Befunge began as experiments — how small can I make a compiler? what if we could jump to another location in code by pointing to it? — and became systems of thought with their own unique logic, ripe for exploration.

Rarely does an esolanger discover the most interesting possibilities of their language on their own; it is others’ experiments that reveal the nuance and character of a language. The first esolang I fell in love with was Piet, named for Piet Mondrian and so pronounced “Pete.” Piet programs are written as a progression of colors in orthogonally pixelated images resembling mosaics or low-fi graphics. Most programs are immediately recognizable as Piet, with its familiar palette and blocky shapes. Yet others counter this aesthetic, perhaps obscuring the Piet program within a larger image with colors outside the language’s palette, or finding their own style within Piet’s strict rules.

A concept is a general direction, and the idea fills in the specifics of that concept.

This collaborative spirit between programmer and language designer comes naturally to free and open source software culture. The scenario the esolanger creates is explored through the programs others write for it, bringing their own sensibility and logic to the project. This interplay reminded me of the constraint-based writing of Georges Perec and the other Oulipians. I immediately wrote my own language in response to Piet.

I began an interview series with esolangers to learn more of their thinking beyond the technical aspects of the work that tend to dominate esolang discussion, and to document the history of the form. This grew into the blog esoteric.codes, which, for 10 years, considered esolang aesthetics alongside code art and code poetry, encouraging a broader context that connects to other computational art.

I noticed that it was common practice for esolangers to keep a to-do list of languages yet to be implemented. These can often be found in the user pages of the esolangs.org wiki, the central archive of these languages. Some stand alone as concepts that don’t need a working interpreter to express their idea: Simply considering the description gives an experience of the language. It runs in our heads. Others are waiting to be crystallized into definitive sets of rules. Sol LeWitt differentiated between the concept and the idea of a work: A concept is a general direction, and the idea fills in the specifics of that concept. Esolangs, a hacker folk art, developed a parallel to this, created by programmers with little interest in conceptual art but also working in an open-ended, dematerialized form. It is just one way these two practices have developed similar habits and strategies in exploring systems, logic, and irrationality.

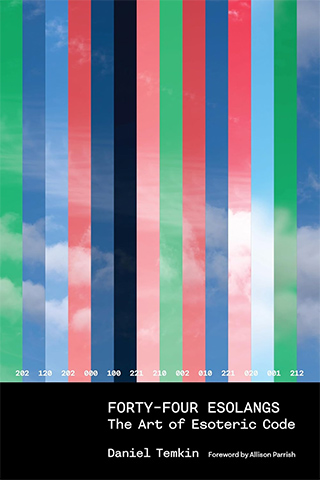

In “Forty-Four Esolangs,” I share 44 esolangs I wrote between 2009 and 2025. Each language is presented first as a Prompt, then as a Realization, mirroring LeWitt’s division of concept and idea. The realization is summarized; full technical definitions or working interpreters are collected at https://danieltemkin.com/esolangs for those who want to experiment further. Sometimes the realization flows naturally from the prompt, but often a single prompt can give rise to many interpretations. Others are left unrealized. This could be because they don’t need implementation, because implementation would lead to logically impossible results, or because their best realization has not yet occurred to me. Mine are not the only possibilities, and I invite readers to interpret the prompts differently.

We write code in idioms and metaphor. Each programming language has two aspects. The syntax — its grammar and lexicon — defines what qualifies as code, splitting texts into those that belong to the language and those that don’t. Its semantics are embodied through a virtual machine providing a set of behaviors the programmer can set in motion. It is a metaphor, as all computers are. The language might make use of familiar abstractions, giving us stacks and memory cells, but it might take the form of a Turing Machine lurking in a solitaire game. It might map easily to the physical box we use to run our code or it might be impossible for our machines to perform.

All the implementations of the languages are open-source and released under the permissive MIT License. Make your own programs, your own implementations, or bring your own vision to them. They are languages, meant to be used.

Daniel Temkin makes photographic and computational art exploring logic and human irrationality. He began interviewing other esolangers and code artists in 2011, creating the blog esoteric.codes. This article is excerpted from his book “Forty-Four Esolangs: The Art of Esoteric Code.”