The Ghost Bird’s Last Song: How a 1935 Recording Became a Symbol of Hope and Controversy

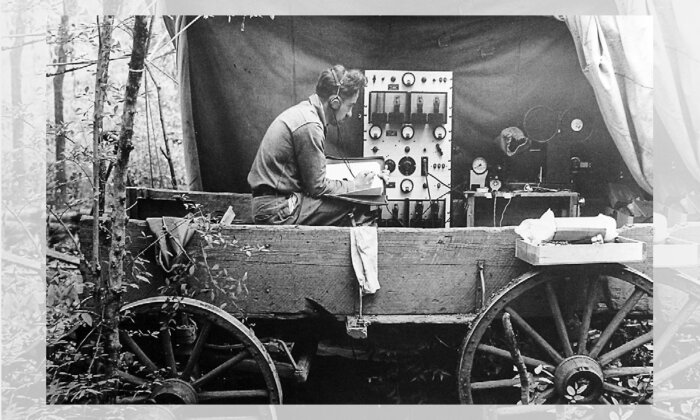

On April 9, 1935, a group of five ornithologists perched on a trunk deep in the heart of the “Singer Refuge,” an area of swampland near Tallulah, Louisiana. The party had stopped during a 15,000-mile round-trip expedition from Upstate New York to study and collect the voices of American birds.

Funded by a former Wall Street investment banker turned ornithologist, Albert Brand, and supported by the American Museum of Natural History and Cornell University, the party planned to document the lives of birds on the brink of extinction. Reports had reached them that the crowning glory of American birdlife, the elusive ivory-billed woodpecker, had been spotted in these marshes. Somewhat more than a decade earlier, the head of the expedition, leading field ornithologist Arthur A. “Doc” Allen, had witnessed a pair of ivorybills singing, but by now advancing loggers and trigger-happy collectors among his fellow ornithologists had made such sights increasingly unusual.

For several days, the party had waded through flooded bayous and muddy virgin forest. When they finally discovered a nest, they hauled in two truckloads of equipment to record the birds’ behavior on photographic plates and sound recording disks.

They had been perfecting their technique in the woods around the Cornell campus for some years, but this kind of wilderness — remote, dirty, and humid — put it to a harsh test. Sitting in their improvised studio for a week, bent over field notes and eavesdropping on the woodpeckers’ calls through earphones, they created a set of recordings that would be the species’ first and only ones. By midcentury, sightings had become extremely rare and the bird was generally presumed extinct.

As the only acoustic reference point for the ivory-billed woodpecker, the 1935 recording now assumed a key role in assessing the evidence for the bird’s alleged rediscovery.

That changed 70 years later, almost to the day, when the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology and the Nature Conservancy jointly published a paper in Science announcing the rediscovery of the species nicknamed “ghost bird.”

Their evidence included a number of sightings and some grainy video material. But with visibility severely limited in the densely forested tracts of Arkansas and Louisiana, the researchers gave special prominence to a series of brief recordings that captured what sounded like the birds’ distinctive double-knock drum and nasal tooting calls. As the only acoustic reference point for the ivory-billed woodpecker, the historic sound recordings of 1935 now assumed a key role in assessing the evidence for the bird’s alleged rediscovery. Mounting new expeditions, the search teams used the recordings to train volunteers and help analysts verify new registrations of possible ivorybills, aided by a programmed pattern-recognition algorithm that scanned hours of automated recordings.

Much was at stake in the validation of these claims of rediscovery, and not just for the ornithologists and academic institutions whose hard-earned reputations were knitted into the evidence they endorsed. Over the course of the 20th century, the ivory-billed woodpecker had become a veritable icon of the American wilderness. A year after the historic sound recordings had been made, the influential American conservationist Aldo Leopold (1936) declared this “Lord God Bird” and “King of Woodpeckers” an inextricable part of the American pioneer tradition, representing a vanishing inner frontier fundamental to the American national character.

A symbol of loss, its presumptive rediscovery also promised a second chance for nature conservation; incontrovertible confirmation of the species’ continued existence would allow conservationists and policymakers to put forward a concrete case for the legal protection and preservation of a large area of land in the southeastern states. The audio, both historic and new, effectively accentuated this emblematic value.

Bird vocalizations have been powerful icons in conservation discourse, nourishing hope and affect from Rachel Carson’s “silent spring” back to the late 19th-century environmental movements that rallied middle-class bird enthusiasts to the cause of wildlife protection. In this discourse, birds’ calls and song served to suggest rapprochement with the natural world and to make the impact of human activity on ecology tangible. Tapping into this symbolism, the specter of an ivorybill calling from across the brink of possible extinction carried deep into the popular imagination.

But however strong its symbolic currency, the recorded evidence also caused a rift in the ornithological community. A vocal group of skeptical ornithologists considered the new recordings too faint, too brief, or too masked by noise to permit conclusive proof of the bird’s existence. They countered the visual and acoustic evidence with their own analyses, mobilizing amplitude displays and audiospectrograms to suggest that the recorded sounds could also be explained by nearby traffic, gunfire, other bird species with similar calls, or even other observers who were mimicking the famous “kent” calls with instrument mouthpieces or broadcasting the historic Cornell recordings in an attempt to provoke a response from hidden woodpeckers. A highly charged trial of testimonials and rebuttals ensued, buttressed by a series of lengthy, expensive, and much-publicized search expeditions. But although ornithologists continue to roam the Singer Refuge today, their searches have not yielded the incontrovertible proof many had hoped for. As the controversy faded from public view, it left the ivory-billed woodpecker suspended between survival and extinction.

What does it take for an ephemeral sound, a faint cry, to be registered under the unsympathetic circumstances of field research, and to be recognized as an object of scientific evidence? How did sound recording come to be considered an authoritative and reliable way of studying wildlife, and why does it continue to be contested nonetheless? And how did the very act of recording animal voices in their own environment change how scientists, and ultimately the public at large, came to listen to them?

My book “Listening in the Field” draws out answers to these questions by tracing a history of the practice of sound recording in the field and its role in the development of birdsong biology. Turning to the analog era of recording between 1880 and 1980, it reconstructs the material and cultural conditions that have allowed sound registrations of wildlife and birds in particular to be crafted, appreciated, and contested — as objects of both scientific investigation and popular fascination.

The practice of recording birdsong took shape at a peculiar intersection of turn-of-the-20th-century popular entertainment, pedagogy, and field ornithology. But in the course of that century, ornithologists, taxonomists, ecologists, and ethologists transformed what had originated as a naturalist fascination with the music-like attractions of living birds into a scientific approach to the study of animal life. In the wake of their discipline’s specialization, biologists of diverse plumage turned to new media and communication technologies to capture and measure sounds for their own specific purposes.

Taxonomists have used sound recordings to investigate species relations, alongside more traditional markers of distinction such as feather coloration or anatomy, resulting in the discovery of new species. Ecologists have deployed sound recording and analysis as a method for tracking, monitoring, and counting species where conventional techniques fail — in hard-to-survey areas such as densely forested tracts or during nightly migrations. Ethologists have developed sound recording into a technique for investigating various aspects of birds’ singing behavior, as an index of how birds learn, inherit, or vary their songs or — by playing back sounds to elicit a vocal reaction — their social functions.

By midcentury, such diverse work had begun to converge in a new interdisciplinary field under the heading of “biological acoustics,” which elevated advanced techniques of acoustic analysis to the status of a methodology for exploring fundamental mechanisms of instinct, behavior, and evolution. Scientists’ investigations were further supported by sound archives across North America, Europe, and elsewhere, which collectively made hundreds of thousands of recordings available for bioacoustic research, analogous to the collections of physical specimens such as eggs, skins, or mounted exemplars that exist in other branches of natural history investigation. In several respects, then, sound recordings became the standard tool to document, study, and preserve the vocal behavior of birds.

But as the ivory-billed woodpecker’s vexed appearances suggest, even in the 21st century the evidentiary value of recorded sound has remained far from undisputed. In fact, the controversy punctuates a far more messy and ruptured history of methodological innovation, in which the fervent instrumentalization of new media technologies in wildlife research gave rise to a long-running and pervasive debate among field biologists regarding the conditions of fieldwork, the calibration of sensory judgment, the epistemic qualities of sound and listening, and so ultimately, the nature of scientific evidence.

In the course of their academic professionalization, ornithologists had learned to trust the tangible presence of captured specimens or — enabled by technologies for extending and disciplining observation, such as binoculars and field guides — a visual identification or observation by peers that could be trusted to be reliable. Sound problematized these evidencing practices. Ornithologists typically relied on auditory cues to guide their work in the field, for instance, when they listened to locate a potential specimen in the field. But transforming such (often tacit) intuitions into a category of proof required a new kind of private experience to be made accessible to a collective of scholars.

For listening to be crafted into a form of scientific observation and data collection, new techniques of description and evidencing had to be contrived, new ways devised for listeners to learn and to convey their findings, and new routines cultivated for calibrating and assessing the reliability of their audition. It also required listeners to define what exactly they were listening to. New sound technologies occasioned and, at least at first glance, also seemed to resolve such questions. But as “Listening in the Field” shows, they actually greatly complicated such issues. For although sound recording technologies promised to relieve listeners by registering, calibrating, and preserving sound for them, they also compelled scientists to engage with a set of practices that were never exclusively scientific nor originally theirs to define.

For sure, many early recording devices had originated as experimental or documentary tools, yet in most cases this scientific use had long been eclipsed by the cultural and commercial appeal of recorded music. It is easy to imagine ornithologists’ attraction to a technological medium whose promise was anchored in a discourse of fidelity and the possibility to transport sound reliably across time and space. But that promise had been defined as much by the needs of advertising, mass communication, and military applications, as by scientific aspirations. When biologists turned to record birdsong in the field, they thus appropriated a class of media technologies whose conditions of use had crystallized within settings as diverse as musical composition, nature teaching, radio broadcasting, gramophone entertainment, hobby electronics, and Cold War surveillance.

It is this tension — between sound recording as a cultural practice and its appropriation as a distinctively scientific technique, between sound as a form of evidence and its cultural existence — that propels the story in my book. In redefining sound recording into a methodology of scientific investigation, these biologists could not avoid grappling with those various conditions of use.

Sound recordings were actively collected, processed, and exchanged with a broader set of purposes in mind than an exclusive use as scientific evidence.

First, making sound recording work in the field required specific resources and expertise that had accumulated over time in these existing milieus, such as infrastructure, equipment, funding opportunities, and networks of communication, along with specialized “sonic skills” — listening skills and techniques to make effective use of the equipment. Second, even as scientific objects, recordings of animal vocalizations retained a broad-ranging commercial, artistic, educational, and sometimes even military appeal. Finally, vernacular meanings and practices of recording continued to pattern how people heard and appreciated recorded sound. Hence, materially, socially, or discursively, sound recording never existed exclusively as scientific practice. Nor was it, however, meant to. In developing and legitimizing sound recording as a scientific technique, scientists used these conditions to their benefit.

When and where sound recording thrived, it did so precisely because ornithologists sought to exploit these links and often managed to repurpose sound recordings beyond the direct circle of their peers who were invested in birdsong. Sound recordings were actively collected, processed, and exchanged with a broader set of purposes in mind than an exclusive use as scientific evidence; as wildlife sound gramophone recordings, radio broadcasts, movie soundtracks, musical compositions, or didactic resources, they traveled back and forth between scientific and popular domains. It is this entanglement of purposes that has helped tie together a broad-based community of listeners in the field, but it has also led them to listen to these recordings and their natural environment in very different ways. As a result, sound recordings have not only documented birdsong but also influenced the very act of listening itself, fostering divergent interpretations and meanings across scientific and popular audiences. Their circulation has blurred the boundaries between disciplines, transforming birdsong from mere data into a shared cultural and ecological experience.

Joeri Bruyninckx teaches in the Department of Technology and Society Studies at Maastricht University. He is the author of “Listening in the Field: Recording and the Science of Birdsong,” from which this article is excerpted.