The Extinction Loop

On May 5, 1725, Leendert Hasenbosch, a Dutch soldier and bookkeeper exiled from his ship for engaging in sexual acts with a lower-ranked sailor, became the first known inhabitant of Ascension Island. Stranded with meager supplies — a tent, a cask of water, a musket without bullets, a bale of rice, two buckets, and an old frying pan — he chronicled his struggle for survival in diaries later found by English sailors. His final entries describe him parched, sucking blood directly from the neck of a bird he managed to catch, and draining the bladder from a turtle to drink its urine. Hasenbosch’s body was never found.

Centuries later, the British Crown claimed the island, transforming it into a testing ground for one of the world’s first large geoengineering endeavors — in this case, focused on reshaping ecosystems — led by Joseph Dalton Hooker and Charles Darwin. Imported plants and seeds from Europe, Africa, and South America created a new ecosystem, turning the volcanic landscape into a hub for imperial ambitions. By World War II, Ascension had become a militarized site for radio transmission and a staging point for aircraft. Today, devoid of permanent residents and accessible only by military transport, Ascension serves as a stark reminder of the power structures that have shaped it across centuries. Its legacy lives on in the libertarian fantasies of tech moguls who are reimagining terra nullius — lands claimed as belonging to no one — as experimental sites for their floating cities and colonies on Mars.

The Drowned, Exiled World

One such vision materializes in the Seasteading Institute, venture capitalist Peter Thiel’s libertarian dream, which features sleek white interconnected hexagon-shaped modules, covered with luxury villas emerging from green patches, and yachts docked along the edges. The glossy structure evokes Norman Foster’s design for the circular Apple Park (headquarters of Apple Inc. in Cupertino, California), but is reimagined as a buoyant, floating architecture, heavily reflecting the brutal radiation the sun casts upon a drowned world.

For Thiel, the impending flooded world of climate collapse is not a catastrophe, but raw material for new geo-markets to emerge. He came close to securing the support of the French Polynesian government for a permanent, autonomous Seasteading settlement off the coast of the South Pacific islands. As rising sea levels threaten the islands’ very existence, the prospect of transitioning to floating islands — even if that would mean transferring partial sovereignty to unelected tech entrepreneurs like Thiel — was seen as a tempting option for the future survival of the “French overseas territory.” But Tahiti locals began protesting what they rightfully perceived as “tech colonialism,” and the temporary agreement was discontinued by the French Polynesian government as a result.

Thiel’s floating island phantasm is low on imagination, as it essentially follows the textbook libertarian scripture known as “Atlas Shrugged”

Thiel’s floating island phantasm is low on imagination, as it essentially follows the textbook libertarian scripture known as “Atlas Shrugged,” a novel by Ayn Rand. The 1957 book describes a near future scenario in which the capitalist entrepreneurial class considers itself overtaxed and hyper-regulated by states, undermining their productivity and creativity. Guided by a mysterious figure known as John Galt, the capitalist moguls are persuaded to go on “strike” against what Galt considers “state looters,” by abandoning their companies to build a new “rationalist” capitalist utopia elsewhere, premised on individual sovereignty and the abolition of the (welfare) state.

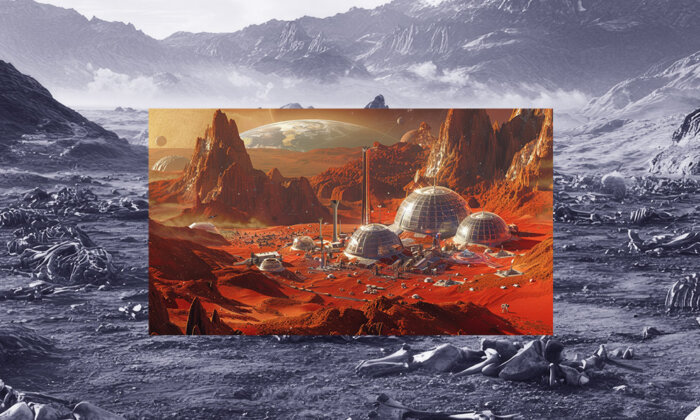

Today, Thiel is far from the only one dreaming of navigating a drowned world, turning the sixth mass extinction into a currency pool for the elite one-tenth of the global 1 percent. Or maybe we should say half of one-tenth of 1 percent. For if half are obsessed with profiting from a drowning Earth, the other half are epitomized by Elon Musk, cofounder of the Space Exploration Technologies Corporation, or “SpaceX,” as well as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who created his own space-faring company, Blue Origin: Their eyes are set on what is to become the terraformed “back-up planet” Mars. In Musk’s words: “We stay on Earth forever and then there will be an inevitable extinction event,” or we can “become a spacefaring civilization, and a multi-planetary species.” For the libertarians, Mars is a “dead planet,” an untapped resource, a fossil waiting to become fuel, just as their colonial ancestors declared vast parts of Earth terra nullius of their own.

In fact, in the agreement that satellite users of the SpaceX subsidiary Starlink have to sign, the 10th clause reads: “For Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.” Referring to Mars as a “free” planet in this context does not mean that either Mars or its future inhabitants will have political agency themselves; rather, it speaks to the proprietary rights of SpaceX to extract and engineer the planet without any governmental or democratic interference. In their terraformed biospheres, the libertarians rule supreme. Extinction is their chance for market expansion, their opportunity to become the world, no matter if it’s a drowned or exiled world. As even then, they can monopolize its ruins.

Designing Extinction

For such projects to move from science fiction and the egos of the ultra-rich to reality, propaganda serves a key role, and an important tool of libertarian climate propaganda is precisely the rendering of this future, making the future visible. The glossy allure of Thiel’s and Musk’s sci-fi inhabitations of drowned and exiled worlds lies in a form of visualization that hides the disasters that enable them to come into being in the first place.

Images of the Seasteading Institute’s floating islands do not evoke the millions of human deaths resulting from a climate shaped by perpetual tsunamis and raging super-fires. Their polished computer models instead function like Apple products, which separate the ruthless reality of the Foxconn factory gulags from the user’s product experience. And so, Thiel’s and Musk’s future renderings show not millions of climate refugees and water wars, but lushly forested floating cities and a greenified Mars where high-tech infrastructures have reduced labor, and the problem of democratic governance is resolved through fully engineered luxury environments responsive to their inhabitants’ every need. The fact that the first Seasteading Institute aimed to host no more than 200 inhabitants, and thus only provides survival residence for the super elite, is of secondary importance to the libertarian allure that “we” could be those chosen ones.

The glossy allure of Thiel’s and Musk’s sci-fi inhabitations lies in a form of visualization that hides the disasters that enable them to come into being in the first place.

Similar to the copycat Randian utopias of Thiel and Musk, libertarian propagandists uncreatively appropriate mainstream science fiction and its CGI arsenal as its main image-rendering machinery. When it comes to the impact of science fiction in shaping our reality and futures, blockbuster Hollywood cinema instantly comes to mind.

The body scan in “Running Man” (1987) is now a structural part of airport life. The electric vehicles in “Gattaca” (1997) are now a Tesla monopoly. Tom Cruise’s use of touch screens in “Minority Report” (2002) prefigured the iPhone and iPad. But this is not an “organic” consequence of major science fiction culture, but rather planned, given that tech-industry and industrial designers product-place technology that they are developing in mainstream science fiction. Thus, viewers and consumers get trained to recognize products that are yet to be launched on the market. Once they are, they become instantly familiar, as the collective imaginary has already been conditioned for their use.

Libertarian climate propaganda has fully appropriated this technique of product-placing the future, for example, in the sci-fi designs of so-called smart city architectures commissioned by Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, owned by parent company Alphabet. In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Schmidt recognized the disaster as an opportunity to pitch his smart city models: high-tech responsive urban environments that turn cities into data architectures. Smart cities are extractive interfaces that harvest information on their citizens’ movements and behaviors, as well as their health, which in the context of the pandemic, responded to an immediate public urgency that could tip city governance in Schmidt’s favor. Place his smart city architecture models next to those of science fiction film designer Syd Mead — who pitched his industrial product designs for decades in films such as “Blade Runner” (1982) and “Tomorrowland” (2015) — and it’s hard not to see the repetition of the same product-placing strategy.

The field of so-called creative industries is an essential component of libertarian climate propaganda, as smart city infrastructures and Mars colonies are pitched not only as consumer-friendly, high-tech, and sustainable solutions for human survival, but also as promises of a certain aesthetic futurism.

Design entrepreneurs like Daan Roosegaarde, who created a glow-in-the-dark “smart highway” of his own, are exemplary for the emerging design forms of our extinction and the aesthetic experience of survival for the Earth’s elites he offers to clients ranging from ING Bank, BMW, and NASA. Roosegaarde’s work “Smog Free Tower” (2015), for example, a sleek 17-meter-high aluminum layered sculpture, provides the illusion of a quick technofix to pull carbon from the air, out of which the “Smog Free Ring” (2017) is made, in which instead of a diamond, there is a condensed black cube of smog particles. Another of his projects, the “Space Waste Lab” (2018), projects green light beams into space, to map the location of an estimated 8 million kilograms of space debris, with the eventual aim of capturing and recycling the polluted trash into new (sellable) products. In all cases, a glossy, sometimes spectacular design product or event is aimed to comfort and encourage us to hand the keys over what remains of our futures to the extinction designer, hoping that the world they promise actually has a place for us.

Following the logics of the libertarian propagandist, Roosegaarde is not concerned with the systems and causes that create pollution but is rather interested in turning pollution into design object merchandise. For him, extinction is not a threat to living worlds, but a design opportunity first and foremost. It is easy to imagine how smog-free towers would litter Thiel’s Seasteading Institute, or how the Space Waste Lab is employed in Musk’s or Bezos’s space colonization programs. Extinction is their shared market. What matters is not what is left for the many, but what services and jewelry are available for the designated trillionaire survivors on their floating cities and Mars settlements. Like the American Dream, the Extinction Dream exists only for the elite’s elite.

The underlying logic of libertarian climate propaganda forms what can be called an “extinction loop”: a self-reinforcing cycle in which libertarians embrace extractive industries that accelerate ecosystem collapse, viewing climate collapse not as a crisis but as a resource. This allows them to construct geoengineered, terraformed, private biospheres under techno-feudalist rule, adorned with extinction design. Their “solutions,” whether carbon-capture or floating infrastructures, are not really solutions, but rather the desirable consequences of the accelerationist planetary disasters they engineered themselves (exemplified in the corporate dystopian cult known as the “Dark Enlightenment.”) In short, extinction is their currency.

Considering the libertarian climate propaganda extinction loop (wherein a false solution to a crisis becomes justification for deepening the crisis itself), there is no contradiction in ruining living worlds by building a predatory energy economy, as this is the point: Libertarian propagation accelerates ungovernability to engineer its own worlds in the old system’s place. The libertarian future, in other words, literally relies on our demise: Just like Leendert Hasenbosch’s bones reside somewhere under the geoengineered biosphere of Ascension Island, the future bones of the many precarious earth workers sent to Mars will be buried under a terraformed world in which they will have no stakes at all.

Bezos’s 2021 press conference, after having just returned from his 11-minute trip to the outer atmosphere in a penis-shaped rocket made by his Blue Origin company, is telling in this regard. Dressed in a blue space uniform topped with a cowboy hat to emphasize his new status as a space pioneer, he stated to the assembled press: “I want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer because you guys paid for all of this.” And work for it they did: uncontracted, banned from unionizing, without social security, forced to pee in bottles and wear diapers to meet production targets in windowless warehouses — all so that their CEO could leave Earth without them.

Jonas Staal is a visual artist and propaganda researcher whose publications include “Propaganda Art in the 21st Century” and “Climate Propagandas,” from which this article is adapted.