The Economy of Painting: Reflections on the Value of the Canvas

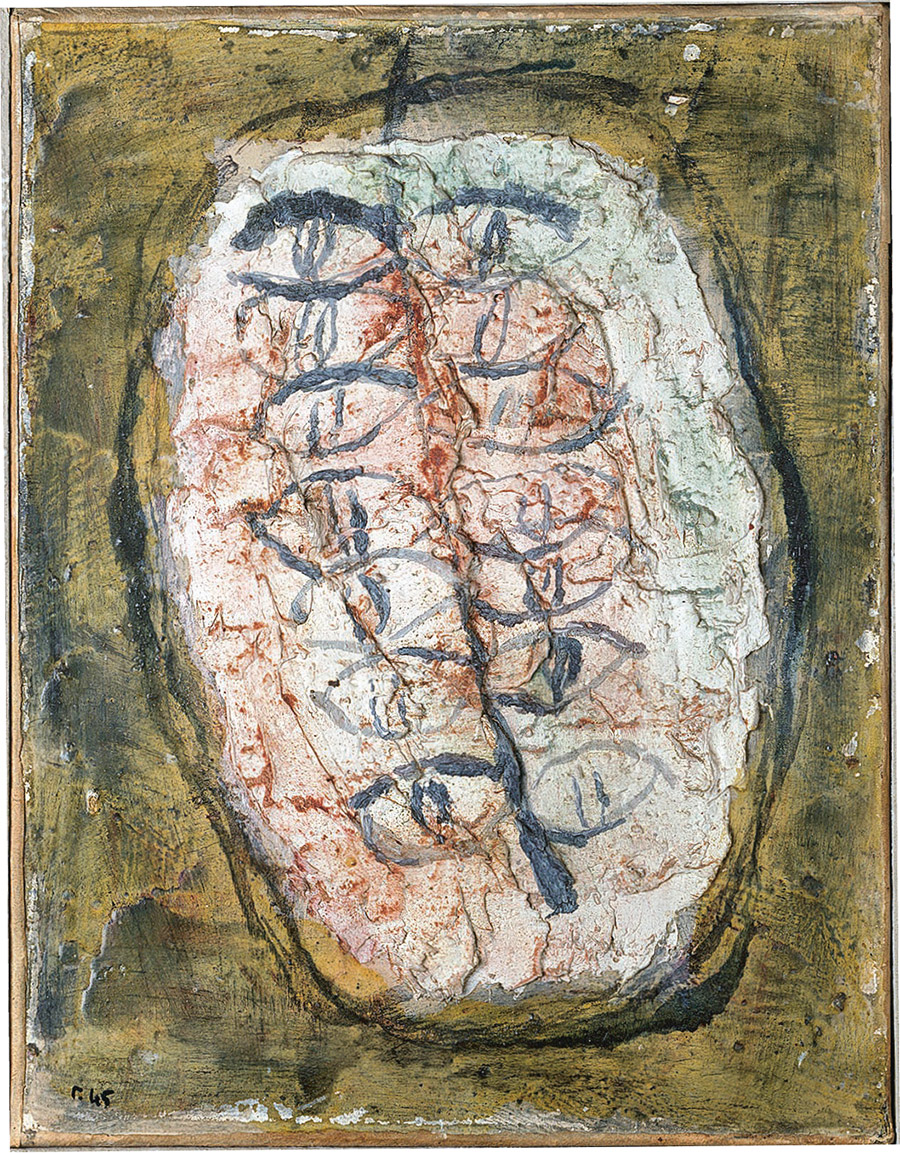

In his notes on Jean Fautrier’s painting series “Hostages” (1943–45), the writer Francis Ponge always mentioned “the painters” in the same breath with “their dealers”: “It would seem that the painters, or their dealers, avidly desire that their pictures occasion words.” The phrasing suggests that the distinction between painters and art dealers is effectively moot, in no small part because their conduct is declared to be identical. They form a kind of community united by a basic mindset, with all their aspirations focused on their pictures.

Ponge’s intuition that painters and their products are intimately involved with commerce (or its representatives, the dealers) can serve as a point of departure for my reflections on the value of painting. Like Ponge, I argue that artists, and especially painters, are inescapably enmeshed in the art trade simply by virtue of their product’s specific value form. In the following, I will show that their work is social to its core, and that artists and painters must therefore be regarded as actors in a capitalist system whose essential objective is the maximization of profits.

What the painters or their dealers wish more than anything, Ponge writes, is that their pictures “occasion words,” that is, that they are written about. In Ponge’s view, this eagerness to be the subject of a textual production is connected to business considerations, which is why it unites painters and dealers. The explicit inclusion of the latter, as the primary commercial actors, identifies the hunger for texts as an exigency also imposed by the market. Of course, Ponge’s essay on Fautrier — it was included in an exhibition catalogue — was apt to enhance the symbolic and market value of the works discussed, an aspect the author made no effort to conceal,1 mentioning not only his fee but also the “one or two of these pictures” he would receive as compensation for his efforts.

Payment in kind — which is to say, in the form of artworks — remains a commonplace practice in the art world today, though it’s rarely talked about. If Ponge was given two paintings by Fautrier as remuneration for his essay, the implication was that he was a direct participant in the speculation on their rising market value, to which his writing was a not inconsiderable contribution. The reflections of a writer who had already made a name for himself no doubt helped establish Fautrier’s pastose “Hostages” pictures with their peculiarly crusty relief-like surfaces as culturally significant and, by extension, symbolically and economically valuable.2 So the formation of value not only involves painters and their products as well as the dealers, but also those recipients who, like Ponge, generate meaning and significance. For a more accurate account of the value form of the painted picture, we will therefore need to combine the production-aesthetic focus on the creative labor and its products with an approach grounded in the aesthetics of reception.

Value Presupposes Commodity Form

It bears emphasis, however, that “value,” in this connection, denotes not a painting’s symbolic value but its “commodity value” — a value that, as Karl Marx argued, is represented and “embodied” exclusively by commodities.3 This value has a thing-like and concrete manifestation, and so it should in principle be identifiable in painted pictures as well: no value without a physical object.4 But the concept of commodity value also implies that, in Marx’s perspective, value attaches only to commodities — to put this central premise of his labor theory of value in the briefest of terms, there’s no value without a commodity. So if works of art, and paintings in particular, are said to be “valuable” in this sense, they must likewise be regarded as commodities. And like the commodity, the painted picture would have to be a good that straddles the distinction between use value, including symbolic value, and economic value.

Payment in kind — which is to say, in the form of artworks — remains a commonplace practice in the art world today, though it’s rarely talked about.

Now commodities, according to Marx, are goods destined for exchange that circulate and change hands. Given their highly mobile quality, paintings would seem to be especially suitable for such transactions: In that sense it might be said that it’s their transportability that predestines them for the commodity form. And in a global economy of the sort that has taken hold in the art world as elsewhere in recent years, paintings circulate more widely than ever. Taken by themselves, they can be regarded as pure products of labor, neither commodities nor values. Yet the moment they’re, say, sold at auction or presented and discussed in the framework of one of the many biennials — which is to say, the moment they’re exchanged for a fee, cash, or symbolic recognition — they’re transmuted into things of value, or in other words, into commodities.

However, we must not identify their commodity value with their price, a common misconception when it comes to ordinary commodities. Marx consistently emphasized the difference between the two: A commodity’s price, he argued, is the monetary name of the labor objectified in it, which is to say, it expresses value in the category of money without itself being that value. It follows that price and value need not match. For Marx, as for Adam Smith before him, value was ultimately based on human labor, but — and this is where Marx diverged from Smith’s conception of value — it had cast off its origin in labor. Smith had declared labor to be the essence of commodity value, but Marx — and that, I believe, is the strong point of his conception of value — disavowed such substantialism. Value, from his perspective, remains related to labor,5 but it has become disassociated from individual labor to become a representation of “human labour in the abstract.”6

Value Is Rooted in Labor and at Once Abstracts from It

Marx defined value as human labor “in its congealed state, when embodied in the form of some object” — a formula that emphasizes its relation to labor as well as the fact that the latter undergoes a transformation: The phrasing “the form of some object” (in German, gegenständliche Form) signals that human labor, in value, is rendered in a thing, which is to say, transmuted into something else. So while value in Marx remains related to concrete human labor, it’s at once also the locus of abstraction from that concrete human labor, it undergoes a metamorphosis into what Marx called “abstract labour.” Abstract labor, Marx wrote, is “undifferentiated human labour” or “labour directly social in its character,” which is to say, a labor stripped of its specific qualities, a universal socially determined labor that comes into being only in the act of exchange. In other words, abstract labor means that different instances of private labor are transformed, in the course of being exchanged for each other, into social labor. What they have in common becomes manifest in the relation of exchange and is represented in their value; the latter abstracts from the concrete individual labor conditions that are invisibly contained in it. This abstract labor in which concrete labor is rendered invisible and made to disappear, Marx argued, constitutes value. So value is difficult to grasp and chimerical and yet necessarily represented in a thing.

Value is difficult to grasp and chimerical and yet necessarily represented in a thing.

This twofold character of Marxian value — that it suggests presence while being premised on the withdrawal of presence — is what makes it an especially suitable tool for the analysis of the value form of works of art and paintings in particular. Engaging with art, one often realizes that the works are not valuable “in themselves.” Their value doesn’t inhere in them; it cannot be located within them. As Marx noted, it’s constitutively relational: It appears in the interrelation between one work, one picture, and another. So with respect to art no less than other commodities, value must be described as a social phenomenon.

The Fetish Character of Painting

The “secret of the commodity form,” Marx wrote, is that it reflects “the social character of men’s labour” back to them as “an objective character stamped upon the product of that labour.” The commodity, in other words, mystifies the labor conditions that produced it — its social dimension — by presenting them as its own intrinsic quality. That’s why, as Marx put it, commodities appear as “independent beings,” and therein lies their “fetishism”: Like fetishes, they’re experienced as quasi-living and self-acting beings because the social character of the labor expended on making them is both rendered invisible in them and perceived as their own nature. Now, the very structure of paintings suggests that they have much in common with this commodity fetish that mystifies its own social dimension. For instance, the canvas tautly stretched over the frame may be described as a firm, smooth, and impenetrable coat that, like the commodity fetish, quite literally covers up its social conditions.

Some recent painterly practices have carried the essential fetishism of painting to extremes. Consider Sarah Morris’s colorful grid paintings in large formats, which foreground their product- and commodity-like qualities. Their extraordinarily glossy and saturated surfaces seem utterly impregnable, an opaque coating that recalls the outer “skin” of lacquered luxury goods such as jewelry boxes or sports cars. As with the commodity fetish, the specific labor that was expended on making these surfaces vanishes from view in contemplating them. They instead function as a kind of mirror of value in which generalized human labor emerges only as a quality that seems inherent in them.

On the other hand, numerous painters of the postwar era have sought to symbolically reveal the concrete conditions in which the painting is made. Take Tagli (“cuts”), for example, the slashed or lacerated canvases by Lucio Fontana, or David Hammons’s work between 2009 and 2011. The selective destruction of the support medium brings what lies “behind” it (the conditions of its production, its social dimension) into play in a variety of figurations. Still, we don’t actually learn anything about these conditions, and so the works only demonstrate again that the painting is a product of labor whose social dimension remains concealed even when the artist strives to uncover it. The painting’s fetish character, it turns out, persists despite the symbolic attempt to dismantle it. Although paintings are structurally analogous to the commodity fetish, they constitute a special kind of commodity.

Painting as a Special Kind of Commodity

Unlike ordinary commodities, paintings are unique material objects, distinguished by their singularity and physical presence. The painting’s uniqueness is directly associated with the singular individuality of its creator, implying a close nexus between person and work that’s authenticated by the signature.7 Its material character can encourage the fantasy that the author’s labor process is immediately contained in it.8 Unlike the commodity fetish, paintings can create the impression that they wear the conditions in which they were created on their bodies as an index of sorts, in the form, for example, of material traces of labor. What’s more, even canvases the painter never actually touched, delegating or mechanizing the process of making the picture, present themselves as “metaphysical indices” by suggesting a spiritual rather than physical connection to their creator.9 So paintings whose production was outsourced nonetheless in a sense contain their author’s initiative. That’s why the painting’s uniqueness as well as specific materiality can spark the precapitalist fantasy that the labor process is, immediately or indirectly, deposited and stored up within it.

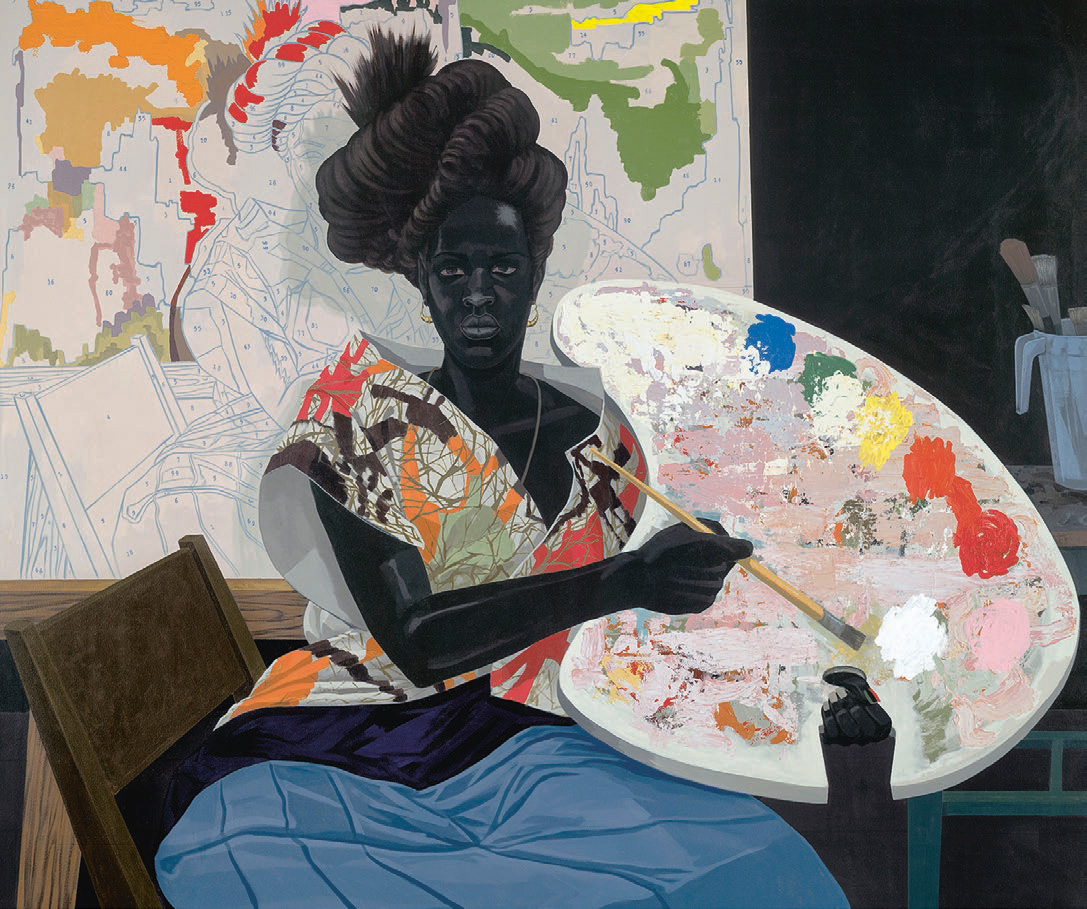

The painter Kerry James Marshall recently found a succinct formula for this twofold character of the painting — it being structurally similar to the commodity fetish while also being unlike any other commodity. In an interview, he described painted pictures as “independent,” echoing Marx’s characterization of the commodity fetish as an “independent being.” This independence, Marshall argued, is highlighted by the comparison with digital images — unlike the latter, they cannot “crash.” They have a durable physical presence that makes them independent also in the sense of not requiring online access or a connection to the power grid.10

Expanding on this description of painted pictures in the categorical framework of the commodity fetish, Marshall added that what makes them special is that they incessantly remind the viewer of the fact that someone made them, which is to say, that physical labor went into them. And this quality of having been made that is apparent in the painting itself, Marshall noted, points to “consciousness,” to thoughts — the consciousness or thoughts, one infers, of the creator. The painted picture’s demonstrative “made-ness” prompts the notion that it’s directly charged with something animate: with its creator’s life. This vitalistic fantasy usually requires a viewer willing to engage in projection, to imagine life into dead matter, an aspect Marshall didn’t mention. Nonetheless, his remarks are a useful reminder that paintings — and this is what sets them apart from ordinary commodities — can nourish the illusion that their value is substantial, and what’s more, that they induce this illusion by virtue of their made-ness.

Painting as a Model Commodity for the Luxury Industry

Painting’s ability to induce the illusion that its value is substantial makes it an ideal commodity, and in recent years the luxury industry has increasingly taken its cue from this ideal: manufacturers have released their industrially produced goods in limited editions to lend them an approximation of the unique work’s aura, or branded them in ways that associate them with an individual author. Both practices aim to make consumers forget the luxury good’s industrial origin and instead establish a mental link to the unique work of art and, more particularly, the singular painting. The most recent testament to the luxury industry’s desire for painting is Louis Vuitton’s “Masters” range of bags (2017), designed by Jeff Koons. Each bag — a version of classic designs of the brand such as the “Neverfull” bag — is printed with a “masterpiece” from the history of painting; the dominant element are the names of the creators (all men) printed in gold letters on top of the images. The monumental lettering not only demonstrates the enormous cultural prestige of painters such as Titian, Rubens, and Van Gogh and excludes women painters from this history once again, but also proves that painting’s products are inextricably bound up with and have in a sense internalized the names of their creators.

Luxury products, in spite of their structural affinity with artworks, can never approximate painting’s special status and intellectual prestige.

The bags make clear that while luxury goods can partake in the enormous symbolic meaning of the “masters,” they can never directly claim that significance for themselves. Final proof of this is the Louis Vuitton logo, which has a strongly reduced presence in the Koons edition. Quite unlike Louis Vuitton’s usual allover branding on its other bags, the logo here seems to yield to the far more significant names of historic painters. Furthermore, the “LV” is combined with another signature, Jeff Koons’s “JK.” Koons, and the paintings he cites, clearly gain the upper hand in this encounter between painting and luxury product, a fact underlined by a reference to Koons’s “signature” work, “Rabbit” (1986), taking the form of a rabbit-shaped tag hanging from a leather strap in matching colors.

The Louis Vuitton brand is here remolded by the Koons brand with his “best of the history of painting” compilation, although allowing itself to be outshone in this way ultimately redounds to Louis Vuitton’s advantage. We can of course point out the common ground that artistic products and luxury goods share as brands: Both depend on an individual authorial name that promises uniqueness, durability, and quality. At the same time, these bags are mass-produced and oddly trashy, reminiscent of souvenirs from a museum shop. Ultimately, in their very trashiness, they supply impressive evidence for the fact that luxury products, in spite of their structural affinity with artworks, can never approximate painting’s special status and intellectual prestige. Although the two classes of products often circulate in the same social sphere, being among the favorite accoutrements of the ultra-rich, paintings remain associated with a claim to symbolic-aesthetic significance buttressed by a long history that luxury products such as Koons’s “Masters” bags aspire to in vain.

Painters Are Not Productive Wage Laborers, but Their Product Implicates Their Labor in Value Formation

The painted picture’s special value form is rooted not only in its manifest made-ness, but also in the intellectual prestige associated with it. The historic privileges that are still accorded to artistic labor, and the painter’s work in particular, likewise inform its value form.

But isn’t it precisely the privileges bound up with creative work that make it incompatible with Marx’s conception of value generation?11 As Marx argued, the productive wage laborer is the sole source of value, including surplus value, which is to say, an excess of labor that goes unremunerated. Although numerous artists, beginning with the historic avant-gardes of the early 20th century, flirted with a working-class habitus — consider, in particular, the Russian Constructivists and the exponents of Minimalism — artists are clearly not wage laborers; unlike the latter, they don’t sell labor power but a resulting product that moreover belongs to them, at least in part, until it circulates, say, in the sphere of art auctions. And even then an artwork remains associated with an artist’s name; he or she is regarded as the sole author and has a monopoly on it.

Still, there are situations in which artistic work does indirectly generate value, as for instance when agents, collectors, or auctioneers make a speculative profit by reselling the artwork. While some of the artist’s labor has been paid for, as when his or her works are sold first, other parts of his or her labor remain invisible and unpaid, especially when profits are made after the artist sells the work. Marx construed profit as deriving from surplus labor, which he defined as unpaid excess labor.

Furthermore, with respect to artistic labor, it’s interesting to note that, in Marx’s view, one and the same kind of labor can be both productive (value-generating) and unproductive (not value-generating) depending on the situation and perspective. In his example, “a singer who sells her song on her own is an unproductive singer. But the same singer, commissioned by an entrepreneur to sing in order to make money for him, is a productive worker,” generating capital. So the same labor can turn out to be productive or unproductive in different constellations. Yet unlike the singer, who sells his or her vocal skills and must be physically present to do so, visual artists, and especially painters, usually make a product that can circulate independently of them (although it’s imaginarily charged with their labor power). And this product — like “all products of art and science, books, paintings, statues, etc.” — does, according to Marx, form part of material production, which is to say, of the totality of relations of production.

In this light, we might say that artists, although they are not productive wage laborers strictly speaking, also remain involved in the generation of value by virtue of their product. And since the painter’s work in particular maintains an imaginary presence in his or her product, the labor is ultimately implicated, by proxy of its product, in the sphere of value formation.

Artistic Work Straddles the Distinction between General and Specific Labor

In the past few years, sociologists have rightly pointed out that the creative and self-determined form of work we typically associate with artists has become the ideal type of labor in general.12 Ostensibly artistic virtues such as creativity, self-reliance, and flexibility are now widely prized in typical working environments. Yet despite this recent convergence between artistic and conventional labor, I would argue that a painter’s decision to engage in self-exploitation by burning the midnight oil still isn’t the same as when a creative worker in an advertising agency puts in overtime. The painter is largely free to set the goals and objectives of his or her work, while the creative worker’s efforts are necessarily geared toward goals and objectives determined by others. The painter owns his or her product, which has a physical existence and is distinguished by its uniqueness. By contrast, the likelihood that the creative worker’s labors ultimately yield a material product is slim, especially in an increasingly digital neoliberal economy. And where the painter’s ideas will be publicly associated with his or her name, the creative worker’s name will be subsumed under the agency’s label. In the creative worker’s perspective, the painter enjoys privileges that he or she can only dream of.

It’s hardly true that nights of boozing and schmoozing or days spent building contacts directly enhance the value of an artist’s work.

It might be argued that, structurally speaking, artists often occupy the social position of the capitalist, for example, when they employ a large team whose unpaid surplus labor they exploit. The artist-entrepreneur model — embodied by Rembrandt, Warhol, Koons, and, most recently, Olafur Eliasson (with few exceptions, an all-male cast) — would suggest as much. Yet even in this scenario the specific quality of artistic work is evident: in comparison to conventional entrepreneurs, these artists are allowed considerable latitude, as their often unorthodox business practices reveal. However much the artist-entrepreneur seems to serve as the matrix for the widely discussed “entrepreneurial self” (Ulrich Bröckling) in the neoliberal economy, he or she can afford to act in ways that would be counterproductive from a strictly economic point of view — in fact, such uneconomic behavior is positively expected of him. In this regard, too, the artist’s work straddles the divide between artistic and general labor rather than unambiguously falling on either side of the distinction. This tension is also reflected by the value form of the product that results from it — its ambiguity between ordinary and special commodity.

Value Also Expresses a Collective Force on the Part of Viewers

To gain a better understanding of the painted picture’s value form, it’s not enough to focus solely on artistic labor and its products. To grasp why different products have different “magnitudes of value,” to use Marx’s term, we must leave the production-aesthetic dimension and turn our attention to the aesthetics of reception, that is, the interaction between art and its viewers. Marx wasn’t interested in the motives of the humans engaging in exchange, in the directions their desires took. In his view, labor time was the measure of the magnitude of value, and as he argued, it was not immediate labor time but only the “socially necessary labour-time,” a sort of quantitative average, that determined that magnitude. With regard to art commodities that claim seems questionable since even works that require no labor time, such as the spontaneously discovered objet trouvé, can have a quantifiable value. Conversely, years spent laboring on a picture doesn’t guarantee that it will attain any magnitude of value. Proposals to expand the conception of labor to include immaterial forms of work, through collaborating or networking, have proved to be insufficient to explain value magnitudes:13 It’s hardly true that nights of boozing and schmoozing or days spent building contacts directly enhance the value of an artist’s work.

On the contrary, nothing suggests that an exhausting social life translates into increased net worth. Value is obviously a function not so much of the totality of an artist’s productive activities as rather of its reception, which is why I agree with the French economist André Orléan that value also must be conceived as the expression of a strong collective receptive force that transcends the individual.14 This force — Orléan calls it affect commun — is invested in certain objects or, in our case, in certain paintings. It operates by way of mimesis, that is, it bends the individuals’ desires toward the objects of the observed or putative desires of others. So the basis of value is a collective imitative desire that confers great value on some things and none at all on others.

It’s important to note that this collective affect doesn’t come from nowhere; it has a long history, has been developed over time by people, and results from social struggles. Artworks can also attract these powerful flows, capturing and distilling them. As a result, the affect commun will invariably navigate toward the artworks. The art world abounds with examples of the mimetic nature of this longing, with numerous collectors chasing after a small set of names. However, the hypostatization of desire implied by Orléan’s affect commun can blind us to the significance of the objects, of what seems to have its origin in them, for the question of value: In a scenario in which desire reigns supreme, no object or picture is especially predestined or entirely unsuitable for the formation of value because of its specific features or of what’s at stake in it at a given moment in history. Desire can fasten on to any object, regardless of how it’s made or what it’s about. Yet as art-world experience shows, it does matter in certain situations what a particular product has to offer, how it intervenes into the formation with which it engages.

So the occasions on which desire is aroused merit scrutiny as well. Still, the trajectory of this collective affective force is not determined solely by the pictures themselves or their allegedly immanent qualities. In the final analysis, value formation also hinges on the narratives — legends and anecdotes, as well as art history and art theory — with which works of art have traditionally been enriched. Such narratives are extrinsic to the works and yet impinge on the core of their being. With their aid, the value of art — in reality a chimera — is lent a semblance of plausibility. The belief in value eagerly seizes on anything that can justify what’s ultimately a precarious construct with no real foundation and lend it an appearance of solidity.

Paintings Are Irreducible to Their Value and Yet Instill the Illusion of a “Life without Negativity”

In closing, I should point out that paintings are more than their value, this excess in turn greatly benefits their value form. In a book on Renaissance painting, Michael Baxandall aptly characterized pictures as “fossils of economic life,” but he also noted that they were such fossils “among other things.” Renaissance paintings represent economic conditions in sedimented form, but to note this is by no means to exhaust them. Baxandall’s studies always evince a keen sense of painting’s economic dimension without reducing it to this aspect.

Similarly, I would argue that paintings must be understood to be things of value, yet things of value of a particular kind, since they foster the (phantasmic) impression that the conditions of their production are directly or indirectly preserved in them. Viewers often project vitalistic fantasies onto paintings, endowing them with human attributes such as authority, self-will, or vigor. These fantasies are vitalistic in that they imagine a life force, or élan vital, that is expressed freely and autonomously without encountering limitations, obstacles, or conflicts. In other words, these fantasies hold out the promise of a “life without negativity,” as Samo Tomšic has put it. “Negativity” is Tomšic’s term for the reality of class struggle, which cuts across the capitalist society and its subjects. Vitalistic fantasies make this reality disappear and replace it with the phantasm of self-willed and autonomous self-realization. They are central to the functioning of capitalism, Tomšicˇ argues, because they can mask the reality of class struggle — the real inequalities, injustices, and relations of exploitation — in favor of the illusion of an unfettered energy. Historically, viewers have often projected just such a self-realizing energy onto paintings, and today, paintings are still a preferred vehicle for these vitalistic fantasies.

When we look at a painting, we are also confronted with dead matter, factual absence, and an author who eludes us.

And yet when we look at a painting, we are also confronted with dead matter, factual absence, and an author who eludes us; a vacancy looms at the heart of the artist’s ghostly virtual presence. Paradoxically, the same materiality that often sparks vitalistic fantasies is also a literal barrier that blocks them: The tangible physical reality of a painting is what resists facile interpretation and cannot be explained away. This irreducibility of the work of art and of the painting in particular, a standing trope in aesthetics since Kant, ultimately contributes to its value form; the more so because the tension between presence and absence, between dead and seemingly animate matter, between commodity fetish and special commodity, cannot be resolved in favor of one side. And anything that defies resolution, that cannot be disambiguated and yet has a durable physical existence, is a source of boundless fascination in an increasingly digital economy.

The focused labor on a material picture we usually associate with painters is in itself a fascinating anachronism in today’s world of social media. Instead of yielding to the ubiquitous distractions or following the ever faster cycle of political or other news online, the painter must be attentive for extended periods of time on a material object he or she manufactures using analogue — or, increasingly, digital — techniques. On a side note, the recourse to digital technology, it seems to me, seeks to assert painting’s contemporary relevance at a time when, simply by virtue of its physicality and the outdated manual craftsmanship associated with it, the conditions of a digital economy threaten to make it obsolete. Painters like Avery Singer and Merlin Carpenter have devised a different way to bridge the gap between their craft and the specific demands of the digital sphere by choosing colors or forms that quote what we might call the Instagram aesthetic. The look of their work is not just an allusion to its online circulation but actually a kind of formal preparation for it: It’s made for the photo blogs on which a growing share of the audience will see it.

In this light, it might be objected that my reflections on value, by taking inspiration from Marx’s theory of labor value, implicitly presuppose the transhistorical validity of his categories. Marx, after all, analyzed industrial society of his time, whereas the paintings whose value form I examine exist in an increasingly digital economy dominated by financial capitalism. But the argument is unconvincing: The industrial society persists, though many aspects of it are now outsourced to so-called low-wage countries. What’s more, the conceptual framework provided by Capital is designed for a theoretical analysis of capitalism’s foundations, not just the observation of a specific phase of capitalism. And since we still live under capitalism, or more precisely, under a particular variant of the capitalist system, I believe it’s entirely legitimate to learn from Marx.

With a view to the influence now wielded by financial institutions, it’s also worth noting that he very much foresaw the growing power of credit.15 The sphere of production, he argued, was closely connected to the circulation of money, and so credit gave the “individual capitalist” absolute control not only over the capital of others, but also over their labor, which is to say, over “social labour.” So the same social labor lies hidden inside financial instruments such as derivatives or options even when they seem utterly disconnected from the real economy.

Unlike the painting, though, the products of the financial industry have thoroughly eclipsed social labor and rendered it invisible. By contrast, the painting’s uniqueness, which points to its singular creator’s specific labor, as well as its materiality (which is read as a trace of that singularity), let it nourish the vitalistic fantasy that the labor of its making is somehow preserved within it. Meanwhile, the same physical presence continually discourages us from indulging in such phantasmic and fallacious inferences. In the end, there is no final answer in how to understand a painting. The fact that the meaning of painting is open-ended, often suspended between different interpretations, also contributes to its value form. As viewers, we return, time and time again, to this thing of value that exceeds its own economic dimension. While painting allows for the fantasy that its value has substance, it also ensures that its value is forever put on hold.

Isabelle Graw is the publisher of the journal Texte zur Kunst, which she cofounded with Stefan Germer (1958–1998) in 1990, and professor of art history and art theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste–Städelschule, Frankfurt am Main. She is the author of several books published by Sternberg Press, including “On the Benefits of Friendship,” “In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017,” “High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture,” and “The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium,” from which this article is excerpted. Her next book, “Fear and Money: A Novel,” will be published in August 2025.

- Unlike today’s art critics, Ponge was recognizably anxious to be transparent about the economic side of his assignment.

- The physical matter accreted on them, Ponge wrote, served “to mask that trace, to bury it,” so that the viewer was “thrown off the track.” The choice of words suggests that the history of Germany’s brutal occupation of France lies buried beneath the surface of these pictures, its presence invisible but palpable.

- Karl Marx, “Commodities and Money,” in Capital, vol. 1, The Process of Production of Capital, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling, ed. Frederick Engels (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1996), 45. Marx’s theory of labor value provides a helpful conceptual scaffold for the attempt to determine the particular value form of the work of art or, in this instance, the painted picture: he explicitly rejected the notion of an “intrinsic” value, which is as popular as ever in the art world and especially in the realm of auctions. Value, Marx argued, must be sought not in a thing itself, but its properties; it expresses a social relation, though one rooted in labor. That’s why Marx allows us to throw the abstract, virtually intangible, and chimerical character of value — including the value of the work of art — into sharp relief without losing sight of its relation to labor.

- That’s why practitioners of immaterial artistic forms such as performance art ensure that their ephemeral appearances leave material traces in the form of props, relics, or documentation. Such concrete physical manifestations are necessary as anchors of value.

- Unlike sociological theories of value — see, most recently, Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre’s “Enrichissement: Une critique de la merchandise” (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, — I follow Marx in insisting on the connection between value and labor, also because it allows for a more accurate understanding of relations of capitalist exploitation. Boltanski and Esquerre define value as a set of justificatory practices that legitimizes or questions prices. Value, in this perspective, is considered solely in relation to price, obscuring the social nexus in which it’s bound up with relations of labor and exploitation

- See Marx, “Commodities and Money,” 51: “But the value of a commodity represents human labour in the abstract, the expenditure of human labour in general.”

- For the manifold implications of the signature, see also Karin Gludovatz, Fährten legen–Spuren lesen: Die Künstlersignatur als poietische Referenz (Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2011)

- Compare the writings of the “new materialists,” who describe matter as energetic, self-acting, and animate. For an introduction, see Susanne Witzgall, “Macht des Materials / Politik der Materialität, in Macht des Materials, Politik der Materialität,” ed. Susanne Witzgall and Kerstin Stakemeier (Zurich: diaphanes, 2014), 13–27.

- For the distinction between “physical” and “metaphysical” indices, see Diedrich Diederichsen, “Art as Commodity,” in “On (Surplus) Value in Art: Reflections” (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008), 42.

- This argument obviously does not apply to digitally generated paintings, a case Marshall does not address.

- See also Merlin Carpenter, “The Outside Can’t Go Outside” (2015); Carpenter strictly distinguishes the artist’s from the wage laborer’s work and likens it instead to the work of an agent who produces a specific kind of value he calls “control value.” This control value is associated with value production and nonetheless specific.

- See most importantly Pierre-Michel Menger, “Portrait de l’artiste en travailleur: Métamorphoses du capitalisme” (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2002); and Ulrich Bröckling, “The Entrepreneurial Self: Fabricating a New Type of Subject,” trans. Steven Black (London: Sage, 2016)

- Diedrich Diederichsen has proposed that we should count the time artists invest in training and in staking out a distinctive position as “socially necessary labour-time” in Marx’s sense; see Diederichsen, On (Surplus) Value, 33. But even if we accept Diederichsen’s extended conception of time and include the artist’s “apprenticeship years” (the time spent at venues such as art academies or bars), it’s hard to see how that explains differences in value. By contrast, Merlin Carpenter has argued that these social activities must not be taken to be value-generating in a strict Marxist sense; see Carpenter, “The Outside Can’t Go Outside.”

- See André Orléan, L’empire de la valeur: refonder l’économie (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2011).

- See Karl Marx, “Division of Profit into Interest and Profit of Enterprise: Interest-Bearing Capital,” in Capital, vol. 3, “The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole,” trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling, ed. Frederick Engels (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1996), 402.