The Clue to the Labyrinth: Francis Bacon and the Decryption of Nature

Even after the scientists have been tested and prepared, and after they wrestle with nature through experiment, the message they receive is still enigmatic. Nature’s message is mysterious even when its text is disclosed. Before Francis Bacon, others had begun to think of nature’s secrets as if they were hidden in code. Bacon’s contribution was to point out that the code may be solvable, something that his contemporaries doubted possible. He even set out a method of solving the code that parallels the techniques of codebreaking used in his time for diplomatic purposes. Though he did not anticipate the power of symbolic mathematics, by invoking the example of codebreaking, he prepared for the later union of mathematics with experimental science.

By the middle ages, thinkers were referring to the “Book of Nature,” meaning that nature and the Book of Scripture both bear divine messages. However, the language in which the Book of Nature was written was hard to determine. In the earlier sources, it seemed that the Book was somehow in a natural, human language, though mysteriously expressed, since the creatures are not “readable” as words or characters. The Book of Scripture offered the prime candidate for the archetypal language. Scripture was the Book of Books, and its study was the touchstone for all interpretation of texts; its enigmas were much pondered, including the famous “writing on the wall” in the Book of Daniel, and pointed to the possibilities of secret writing. In fact, the Hebrew scriptures themselves display several ways to disguise words by substitution, which are among the earliest known ciphers.

Code and ciphers substitute certain symbols (the encrypted text) for the plain text. A cipher operates letter by letter, so that “Science” might be enciphered as “Uelgpeg”; codes work on larger groups of symbols, so “Science” may be encoded as “Sphinx.” The few references to secret communications in ancient sources utilize only the simplest sorts of codes or secret writing; ancient writers thought it amazing that Caesar disguised his dispatches by substituting (say) a by E, b by F, and so forth, a simple cipher now used by children. In medieval times, literacy was so rare that any writing was effectively secret. Islamic-Spanish culture was the source for the later concept of cipher; the Arabic word ṣifr means zero, as in: “he’s only a cipher.” In late medieval France and Italy, there was a fashion for “emblems” or “devices,” hieroglyphic images capable of representing a concept without using words. Many Renaissance scholars tried their hand at these emblems, inventing new hieroglyphs on the model of the ancient Egyptians and thinking further about the possibilities of encoding messages in symbols.

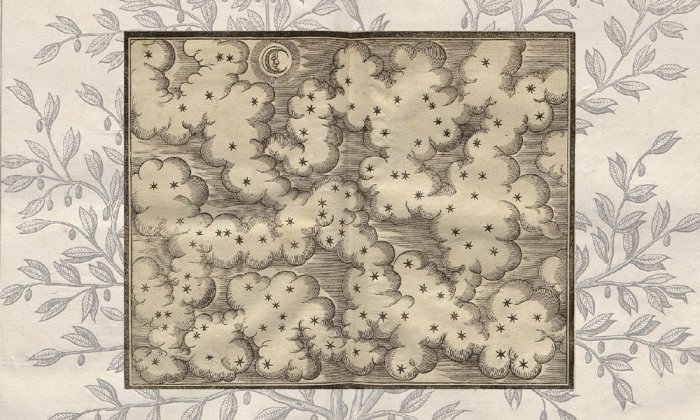

The 16th-century cryptologist Blaise de Vigenère assumed that stars or plants encrypted their divine message in a natural, human language.

Complex cryptography emerged fully during the late middle ages and Renaissance. By Bacon’s time, diplomatic correspondence was routinely enciphered. The intercepted dispatches of foreign powers were opened and, at least in Italy, France, and England, subjected to attempts at cryptanalysis. This modern word denotes the solution of a ciphered text by unauthorized persons; the intended readers “decipher” it. The development of techniques of cryptanalysis was quite late. Its first efflorescence seems to have been in Venice, in the early years of the 16th century, but soon there were master codebreakers elsewhere in Italy and France. Those familiar with sophisticated ciphers began to associate them with the Book of Nature. In 1586, the French diplomat and cryptologist Blaise de Vigenère wrote that “all nature is merely a cipher and a secret writing,” as if this were already a familiar concept. However, Vigenère assumed that stars or plants encrypted their divine message in a natural, human language, on the model of certain ciphers known to him that could hide a given text in musical scores, or in the positions of stars in the sky.

Vigenère denied the possibility of solving the divine cipher through human artifice; not only is the cipher too difficult, but also men are too corrupt. He thought that only through the esoteric Hebrew kabbalah did God permit his elect access to his cipher by providing them with the divine alphabet. They must follow an ancient esoteric tradition strictly, not question or strike out anew. The chosen few may learn ancient mysteries, but must keep the secret from the profane world. Vigenère thought that codebreaking, even of human ciphers, was “a priceless cracking of the brain, and finally a quite inglorious labor.” Despite his knowledge of the practical success of others, Vigenère was sure that codebreaking was futile in all but easy cases.

In fact, there were already available powerful techniques of codebreaking that Vigenère pessimistically ignored. Bacon showed considerable awareness of these new advances in the art of secret writing and had direct contact with its practitioners. His brother, Anthony, spent most of his time on the Continent, in charge of a number of “correspondents,” who acted as spies abroad. In 1586, enciphered letters of Mary Queen of Scots were intercepted and cryptanalyzed, revealing a plot to assassinate Elizabeth, incite a Catholic uprising in England, and bring Mary to the English throne. The revelation of the exact texts of these letters gave evidence of Mary’s complicity and led to her execution in 1587. Cryptanalysis also gave valuable evidence concerning Spanish designs on the English crown.

No one privy to these great events could miss the significance and utility of cryptography, and it surely was not lost on Francis Bacon, then 26 and at the beginning of his parliamentary career. Bacon spoke on the “Great Cause” of Mary’s case as it was deliberated in Parliament. Through Anthony he must have gained further insight into the use of ciphers in more hidden affairs of state. Though Bacon constantly points to the reserved nature of things, he does so in order to disclose those secrets, always excepting divine matters and the secrets of the human heart. As Lord Chancellor, Bacon continually had to decipher King James’s hidden intent, whether expressed in cryptic comments or the elaborate symbolism of the court masques the king cultivated.

Bacon considers ciphers central to the “Art of Transmission,” the general study of discourse and writing. His interest goes beyond common letters and languages; he is interested in Chinese characters, as well as in the sign language of the deaf. Chinese he describes as being formed of ‘‘real characters,’’ which represent things themselves, as do Egyptian hieroglyphics and gestures. These early forms of “transmission” unlocked important possibilities. An ancient tyrant once sent a messenger to a neighboring king; the messenger was to greet the king and then cut down the highest flowers in his garden. The gestures bewildered the messenger, but the cruel message was faithfully conveyed: Kill the nobles. This “transitory Hieroglyph” fulfills some of the requirements of secret communications that Bacon lays down, “that they be easy and not laborious to write; that they be safe, and impossible to be deciphered; and lastly that they be, if possible, such as not to raise suspicion.”

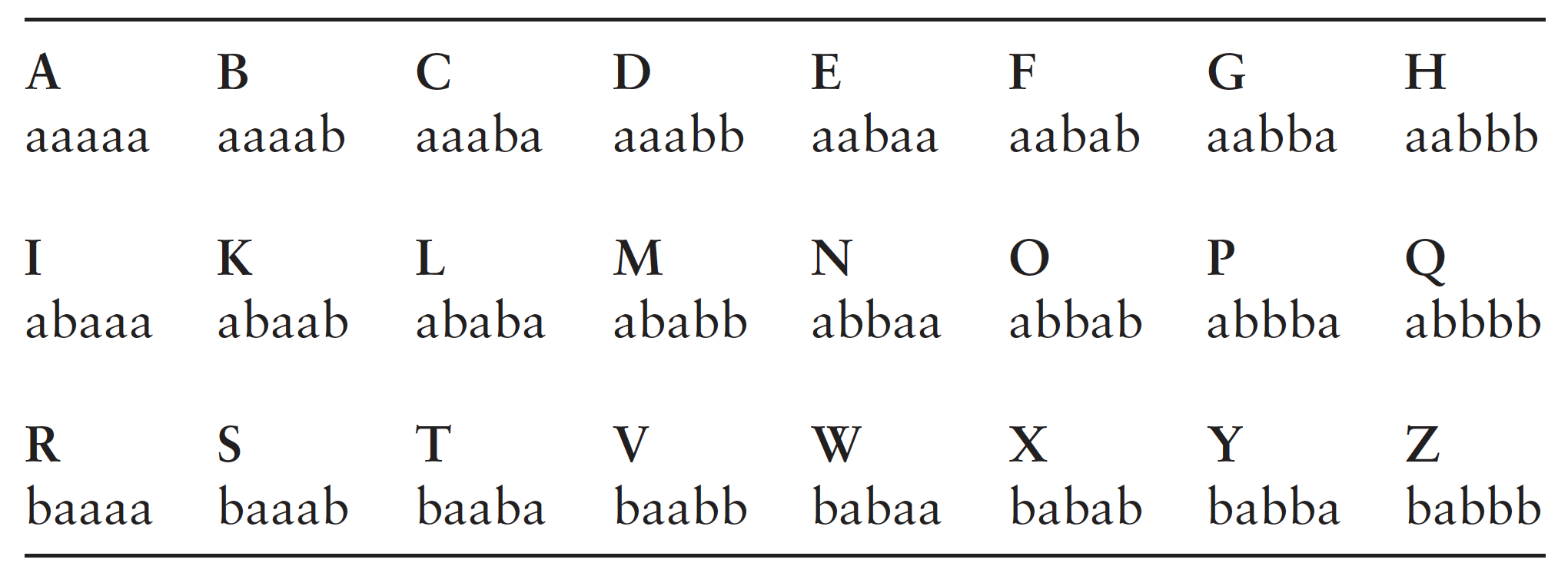

Bacon notes even more powerful ways to transmit and hide a message. As an example, he describes a cipher he devised as a young man, the single discovery for which he claims personal credit. Bacon is proud of this work, “for it has the perfection of a cipher, which is to make anything signify anything.” That is, his cipher will hide any plain text in any cover text, given only that the encrypted text is at least five times longer than the plain. Bacon’s biliteral cipher involves two stages. In the first, he represents the letters of the alphabet in terms of two letters only, arranged in groups of five (see table 1).

Instead of a and b, one could have used any two recognizably different symbols; two different symbols transposed through five different places yield 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 32 different possibilities, enough to include all 24 letters of the English alphabet. Bacon notes that the “differences” need not even be between letters; instead of the letters a and b, one could use two bells of different pitch, or two different gunshots or torch signals. Thus this code is able to remove the letters from language and yet can reconstitute its meaning for the recipient. This feature, which it shares with gestures and “real characters,” already renders it more fit to be a code of things rather than of words alone; it may be a step toward the symbolic code of nature, even though it is invented to serve the conventions of human communication. This code is also binary, like the code widely used for the machine language of computers.

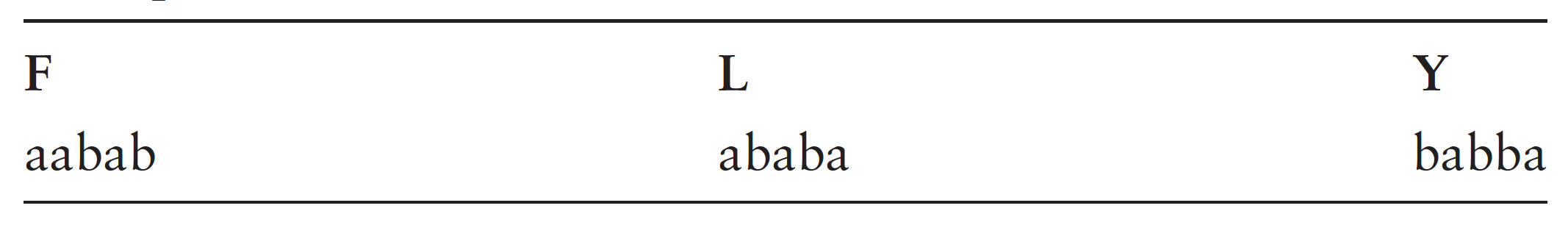

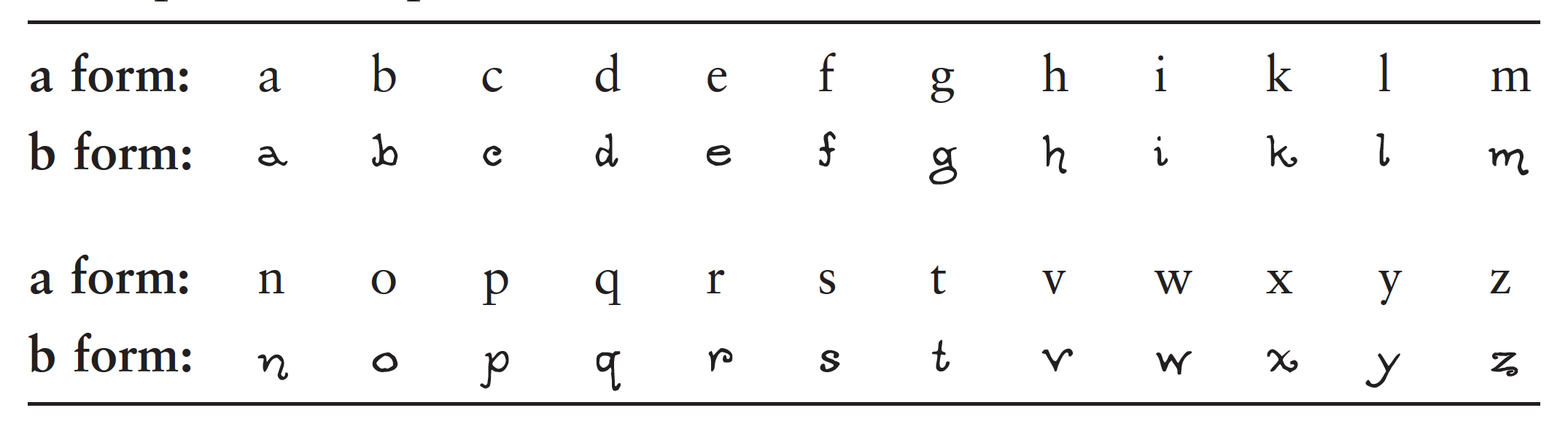

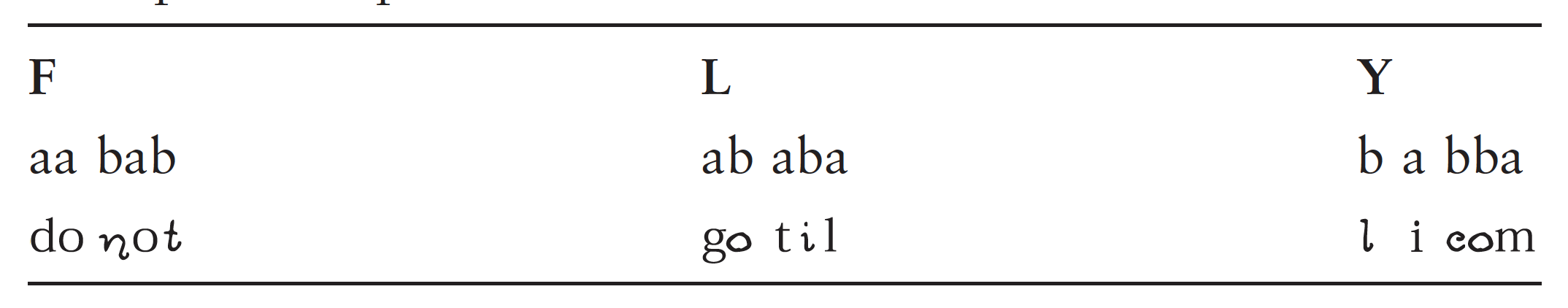

Bacon then embeds this code into a cover text, probably because a stream of “differences,” of gunshots or patterned bell ringing, might excite suspicion, or might be too difficult to convey with sufficient accuracy. Thus Bacon reduces the plain text FLY using the two-letter alphabet (see table 2). He then uses two different ‘‘forms’’ (fonts) of the alphabet, an ‘‘a’’ and a ‘‘b’’ form, similar enough so as not to arouse suspicion and yet different enough to register the difference between the forms (see table 3). Using these two very slightly different alphabets Bacon can then encode the plain text “FLY” into the innocent cover text, “Do not go till I come” (see table 4).

His example relishes the code’s ability to convey just the exact opposite of the plain text in its cover text, not only avoiding suspicion but even misleading the enemy by a text that can mean exactly the opposite of what it seems. Bacon indicates that, if the ancients had used his cipher, they could have escaped detection and fooled their enemies. Despite its cleverness, Bacon’s cipher does not seem to have had any actual usage in the diplomatic practice of his own time, which relied on far simpler devices. His cipher violates his own first rule, that it “be easy and not laborious to write,” for minute variations of typography must be carefully guarded in order to render accurately the two different alphabets required. Bacon seems aware of such objections, for he complains of “the rawness and unskillfulness of secretaries and clerks in the courts of kings,” on account of whom “the greatest matters are commonly trusted to weak and futile ciphers.” He evidently had learned of this practical limitation on cryptographic ingenuity either the hard way himself or through the testimony of others. His publication of the biliteral cipher was a call for greater cryptographic security through stronger ciphers and more skillful clerks. Because of these practical limitations, such improvements were not implemented until several centuries later.

Bacon’s interest in ciphers goes beyond their purely diplomatic use. His cipher suggests a more keen and suspicious reading not only of any given text, but also of any system of “differences,” such as Bacon says may be found in anything seen or heard — that is, anywhere in Nature. This larger goal eclipses the narrower one of improving diplomatic ciphers, for which concealing a new sort of cipher would be the logical step, rather than publishing it. Bacon’s readings of ancient fables are really “decodings.” The outward symbols are “a veil, as it were, of fables,” concealing hidden depths. He remarks that “religion delights in such veils and shadows, and to take them away would be almost to interdict all communion between divinity and humanity,” so deeply are they required for the communion of such diverse and unequal minds. Parables were meant originally not to conceal the meaning, but to make it better understood. For instance, each detail of the Sphinx has a precise analogy with some aspect of Science. Likewise, nature’s enigmatic messages are not perversely obscure; rather, we are too dull and impatient to solve them. His writings teach us an art of interpretation through decoding.

Nature’s enigmatic messages are not perversely obscure, believed Bacon; rather, we are too dull and impatient to solve them.

Bacon did not presume that the book of nature is written in any human language, even veiled by cipher. His crucial insight is that the methodical decryption of nature must grapple with a “language” that requires a whole new order of interpretation. Indeed, Bacon’s yoking of interpretation with nature represents a great shift in understanding. For Aristotle, it is not nature that needs interpretation, but human language. For Bacon, “interpretation is the true and natural work of the mind when freed from impediments.” Those impediments include the radical flaws in human understanding, beset with idols, and the labyrinthine intricacy of the world itself. The ancient labyrinth concealed the Minotaur that devoured Athenian children until Theseus killed it and escaped by means of a thread, or “clue.” Bacon, the author of “The Clue to the Maze,” presents himself as a new Theseus, delivering humanity from the Minotaur of death by scientific secrets wrested from the labyrinth.

Just as Daedalus both built the labyrinth and found its deciphering clue, Bacon calls on science to breach the inmost sanctuary. Salomon’s House is prepared to penetrate the veil over nature through a certain kind of interpretation whose key Bacon calls “induction.” To find this key, Bacon envisaged a symbolic and schematic “alphabet of Nature.” This key is not a fixed structure like a skeleton key, but rather a “key” in the cryptographic sense: a flexible indicator that guides decryption by delineating the structure of the cipher as it emerges. The essential preparation for induction is the exhaustive preparation of “tables and arrangements of instances, in such a method and order that the understanding may be able to deal with them”; Bacon also organizes his “alphabet of Nature” in similar tables. He cannot give full examples; however, he does give an extended attempt at tables regarding the nature of heat, leading to results strikingly like the modern view, in which heat is a form of atomic motion. What is important here are the tables themselves, which are manifold and detailed, going through many possible permutations of the instances, enumerating instances of “essence and presence” or “proximity where the nature of heat is absent” or “exclusion” or “degrees” of heat. These tables resemble the tables used for encipherment and decipherment, though applied here not to a natural language, but to “things themselves.” A cryptanalyst examines the possible correlations between the appearances of certain letters in the cipher text, singly or by pairs or triplets, arranging the results in tabular form. Read negatively, this table also shows which ciphered letters are not correlated with which others. Other tables note the order in which letters are correlated, preceding or following others. Likewise, Bacon’s tables marshal parallel data for heat, citing all known correlations and exclusions.

From the earliest sources on, cryptography had relied on such tabular arrays to give the visible key for the encipherment and, later, decryption. Given Bacon’s detailed knowledge, it seems very likely that either he himself tried his hand at cryptanalysis, saw such work in progress, or heard accounts of it. His posing of a new, more secure cipher shows that he was fully aware of the powers of expert cryptanalysts and, quite likely, of their detailed methods. He certainly sets out his own biliteral cipher in tabular form. The cryptanalyst’s tables are the necessary starting point to break the cipher in a systematic way. After that, certain deeply embedded linguistic features (such as the frequency of the letter “e” in English) can be much more readily brought to light and form the opening wedge to full solution. Bacon’s tables proceed by the same logical categories of inclusion and exclusion, of quantity and correlation, that give the cryptanalyst’s tables their revelatory power. In both cases, the tables are the beginning of reading, with all the interpretative acuity that word suggests. Telling passages in the cipher text must be located and probed; hypotheses need to be formed and tested, even if finally discarded, in order that correct order might finally emerge.

Both cryptanalysis and Bacon’s hunt for the inner forms of nature require imaginative leaps that go beyond merely pedestrian accumulation of data. Although Bacon calls for a science that should be done “as if by machinery,” he is also aware of the importance of the exceptional individual. The Fathers of Salomon’s House are few, yet they rely on many others for the immense work of collecting instances. Only select minds can make the leap from the tables to the unifying insight that completes the work of discovery. Bacon gives images of these singular discoverers in his mythical tales; the solvers of the labyrinth are not to be confounded with their crews and companions, however valuable. The key to the labyrinth is a delicate thread that must be handled with care, for it might break. Bacon thought that true reading of the Book of Nature was reserved to those few who could follow the thread; the rest of humanity — including the wise king of Bensalem — must wait.

Moreover, even the scientists cannot anticipate what is to come; the great discoveries of the past had been quite unexpected. Genuinely new interpretations must “seem harsh and out of tune, much as the mysteries of faith do.” He was wise enough to anticipate that he, too, would be surprised by what was to come. Experience can only be fully appreciated as it emerges, and not before. To read the Book of Nature means to experience it, to experiment with it, even at the risk of destroying old certainties. He envisioned a bridge between symbols, the “alphabet of nature,” and things themselves. In so doing, he discerned a fundamentally new approach to the Book of Nature that transformed the character both of the Book and, finally, of Nature itself.

Peter Pesic, writer, pianist, and scholar, is Director of the Science Institute, Musician-in-Residence, and Tutor Emeritus at St. John’s College, Santa Fe. He is the author of several books, including”Labyrinth,” from which this article is excerpted.