Ten Tips for Cultivating Creativity, From the Director of the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at MIT

There’s a common misconception that the best way to encourage children’s creativity is simply to get out of the way and let them be creative. Although it’s certainly true that children are naturally curious and inquisitive, they need support to develop their creative capacities and reach their full creative potential.

Supporting children’s development is always a balancing act: how much structure, how much freedom; when to step in, when to step back; when to show, when to tell, when to ask, when to listen.

In putting together this list, I decided to combine tips for parents and teachers, because I think the core issues for cultivating creativity are the same, whether you’re in the home or in the classroom. The key challenge is not how to “teach creativity” to children, but rather how to create a fertile environment in which their creativity will take root, grow, and flourish.

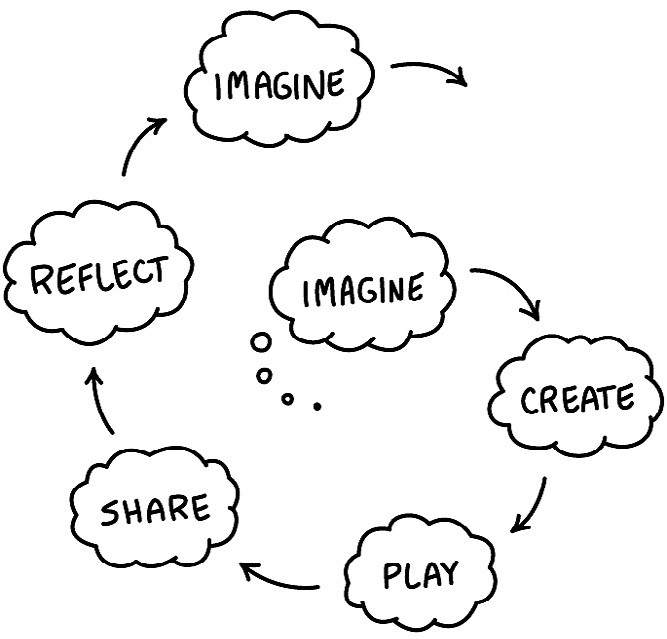

The list is organized around the five components of what I call the Creative Learning Spiral, a process that encourages children to imagine what they want to do, create projects through playing with tools and materials, share ideas and creations with others, and reflect on their experiences.

For each of the five components, I’ve suggested two tips. That’s a total of 10 tips. Of course, these tips are just a very small subset of all of the things you might ask and do to cultivate children’s creativity. View them as a representative sample, and come up with more of your own.

IMAGINE:

1) Show examples to spark ideas

A blank page, a blank canvas, and a blank screen can be intimidating. A collection of examples can help spark the imagination. When we run Scratch workshops, we always start by showing sample projects — to give a sense of what’s possible (inspirational projects) and to provide ideas on how to get started (starter projects). We show a diverse range of projects, in hopes of connecting with the interests and passions of workshop participants. Of course, there’s a risk that children will simply mimic or copy the examples that they see. That’s OK as a start, but only as a start. Encourage them to change or modify the examples. Suggest that they insert their own voice or add their own personal touch. What might they do differently? How can they add their own style, connect to their own interests? How can they make it their own?

2) Encourage messing around

Most people assume that imagination takes place in the head, but the hands are just as important. To help children generate ideas for projects, we often encourage them to start messing around with materials. As children play with LEGO bricks or tinker with craft materials, new ideas emerge. What started as an aimless activity becomes the beginning of an extended project. We’ll sometimes organize mini hands-on activities to get children started. For example, we’ll ask children to put a few LEGO bricks together, then pass the structure to a friend to add a few more, then continue back and forth. After a few iterations, children often have new ideas for things they want to build.

CREATE:

3) Provide a wide variety of materials

Children are deeply influenced by the toys, tools, and materials in the world around them. To engage children in creative activities, make sure they have access to a broad diversity of materials for drawing, building, and crafting. New technologies, like robotics kits and 3-D printers, can expand the range of what children create, but don’t overlook traditional materials. A Computer Clubhouse coordinator was embarrassed to admit to me that her members were making their own dolls with “nylons, newspapers, and bird seed,” without any advanced technology, but I thought their projects were great. Different materials are good for different things. LEGO bricks and popsicle sticks are good for making skeletons, felt and fabric are good for making skins, and Scratch is good for making things that move and interact. Pens and markers are good for drawing, and glue guns and duct tape are good for holding things together. The greater the diversity of materials, the greater the opportunity for creative projects.

4) Embrace all types of making

Different children are interested in different types of making. Some enjoy making houses and castles with LEGO bricks. Some enjoy making games and animations with Scratch. Others enjoy making jewelry or soapbox race cars or desserts — or miniature golf courses. Writing a poem or a short story is a type of making, too. Children can learn about the creative design process through all of these activities. Help children find the type of making that resonates for them. Even better: Encourage children to engage in multiple types of making. That way, they’ll get an even deeper understanding of the creative design process.

PLAY:

5) Emphasize process, not product

Throughout this book, I’ve emphasized the importance of making things. Indeed, many of the best learning experiences happen when people are actively engaged in making things. But that doesn’t mean we should put all our attention on the things that are made. Even more important is the process through which things are made. As children work on projects, highlight the process, not just the final product. Ask children about their strategies and their sources of inspiration. Encourage experimentation by honoring failed experiments as much as successful ones. Allocate times for children to share the intermediate stages of their projects and discuss what they plan to do next and why.

6) Extend time for projects

It takes time for children to work on creative projects, especially if they’re constantly tinkering, experimenting, and exploring new ideas (as we hope they will). Trying to squeeze projects into the constraints of a standard 50-minute school period — or even a few 50-minute periods over the course of a week — undermines the whole idea of working on projects. It discourages risk-taking and experimentation, and it puts a priority on efficiently getting to the “right” answer within the allotted time. For an incremental change, schedule double periods for projects. For a more dramatic change, set aside particular days or weeks (or even months) when students work on nothing but projects in school. In the meantime, support after-school programs and community centers where children have larger blocks of time to work on projects.

SHARE:

7) Play the role of matchmaker

Many children want to share ideas and collaborate on projects, but they’re not sure how. You can play the role of matchmaker, helping children find others to work with, whether in the physical world or the online world. At Computer Clubhouses, the staff and mentors spend a lot of their time connecting Clubhouse members with one another. Sometimes, they bring together members with similar interests — for example, a shared interest in Japanese manga or a shared interest in 3-D modeling. Other times, they bring together members with complementary interests — for example, connecting members with interests in art and robotics so that they can work together on interactive sculptures. In the Scratch online community, we have organized month-long Collab Camps to help Scratchers find others to work with — and also to learn strategies for collaborating effectively.

8) Get involved as a collaborator

Parents and mentors sometimes get too involved in children’s creative projects, telling children what to do or grabbing the keyboard to show them how to fix a problem. Other parents and mentors don’t get involved at all. There is a sweet spot in between, where adults and children form true collaborations on projects. When both sides are committed to working together, everyone has a lot to gain. A great example is Ricarose Roque’s Family Creative Learning initiative, in which parents and children work together on projects at local community centers over five sessions. By the end of the experience, parents and children have new respect for one another’s abilities, and relationships are strengthened.

REFLECT:

9) Ask (authentic) questions

It’s great for children to immerse themselves in projects, but it’s also important for them to step back to reflect on what’s happening. You can encourage children to reflect by asking them questions about their projects. I often start by asking: “How did you come up with the idea for this project?” It’s an authentic question: I really want to know! The question prompts them to reflect on what motivated and inspired them. Another of my favorite questions: “What’s been most surprising to you?” This question pushes them away from just describing the project and toward reflecting on their experience. If something goes wrong with a project, I’ll often ask: “What did you want it to do?” In describing what they were trying to do, they often recognize where they went wrong, without any further input from me.

10) Share your own reflections

Most parents and teachers are reluctant to talk with children about their own thinking processes. Perhaps they don’t want to expose that they’re sometimes confused or unsure in their thinking. But talking with children about your own thinking process is the best gift you could give them. It’s important for children to know that thinking is hard work for everyone — for adults as well as children. And it’s useful for children to hear your strategies for working on projects and thinking through problems. By hearing your reflections, children will be more open to reflecting on their own thinking, and they’ll have a better model of how to do it. Imagine the children in your life as creative thinking apprentices; you’re helping them learn to become creative thinkers by demonstrating and discussing how you do it.

Mitchel Resnick is Professor of Learning Research at the MIT Media Lab. His research group develops the Scratch programming software and online community, the world’s largest coding platform for kids. He has worked closely with the LEGO company on educational ideas and products, such as the LEGO Mindstorms robotics kits, and he co-founded the Computer Clubhouse project, an international network of after-school learning centers for youth from low-income communities. He is the author of “Lifelong Kindergarten,” from which this article is excerpted.