Telling Stories in Virtual Reality: In Conversation With Laurie Anderson (2018)

The following interview was taped on May 1, 2018, and published in Performing Arts Journal Vol. 40, Issue 3.

As a performer, visual artist, composer, poet, and filmmaker, Laurie Anderson has been at the forefront in using technology in the arts since the beginning of her career more than four decades ago. Works such as “United States I-V” (1983), “The Nerve Bible” (1995), “Homeland” (2008), “Delusion” (2010), and “Habeas Corpus” (2015) variously encompass storytelling, invented instruments, animation, installation, film and electronic media, and music.

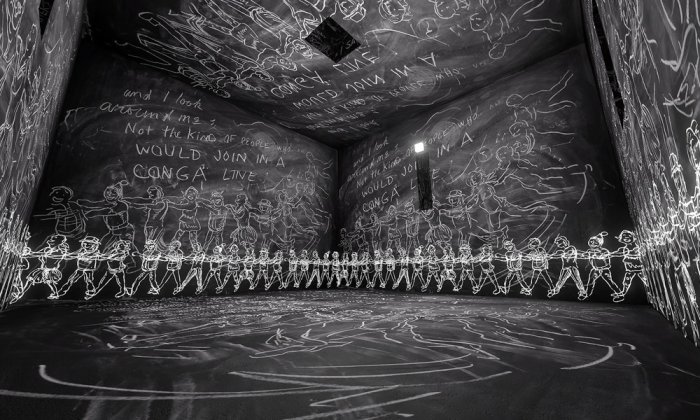

In 2002, Anderson became the first artist-in-residence at NASA, reflecting her long-time interest in science and outer space. Her recent activity includes “Landfall,” a collaboration with the Kronos Quartet; a new book, “All the Things I Lost in the Flood”; and worldwide exhibitions and artist residencies, the latest at Home of the Arts, Gold Coast, Australia. Her new virtual reality work, “Chalkroom” (made with Hsin-Chien Huang) is on view through 2018 at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts, along with another VR piece for headphones, “Aloft,” and her large-scale drawings “Lolabelle in the Bardo.”

Bonnie Marranca: It’s a long arc from the magnetic tape on the violin bow in the 1970s to the virtual reality of “Chalkroom.” How much does your work evolve in relation to available technologies?

Laurie Anderson: I tend to gravitate towards new things just to try them out, see how they work. And if they can do something that I’m interested in, I’ll try working with them. If they can’t, I try not to do it just for the sake of doing something new. The glitzy box has some appeal to me, I have to admit. But when I first started working with VR when my collaborator asked me to do it, I said, “No, I don’t want to do it.” Because it’s such an unpleasant visual language. It’s bright, flat, it’s also very oriented to gaming structures. I thought, I have no interest in this. Keeping score has never been my forte. I said, “Not really, unless, I can make it very homemade and very dusty and full of stuff.” We kind of invented a language that’s a very atmospheric visual language. That made it possible for me to work in it.

BM: How did you and the Chinese media artist Hsin-Chien Huang start working together on the piece?

LA: He was my collaborator on “Puppet Motel” in the mid-nineties.

BM: Oh, I’ve got that piece.

LA: It is not playable on anything anymore, but anyway. It was in the mid-nineties. There was a company called Voyager, and that was Bob Stein’s company. He basically decided to publish the electronic work of artists. We’d been waiting for that. He began to do the work of Bill Viola and a bunch of other video artists. It didn’t take off because people didn’t want to have that at home. That was a bet that just didn’t pay off. But, in the meantime, I did this CD-ROM. Same thing. It just didn’t happen in that world. But we had a really wonderful time making “Puppet Motel,” and then we also made some other things in the late nineties. We’ve worked together every once in a while over the last few years.

BM: Did you collaborate while in different cities? Were you working on different aspects of the technology and the drawing?

LA: Well, he came to New York and we did things here in the 1990s. Now, we work on Skype, which is a really wonderful way to work on ideas. Once in a while, he comes here, or I come there. So, it’s a really nice collaboration, you know. We get a lot done.

BM: In my mind, I had usually identified the virtual reality experience as the flat, cold screen of video gaming, which didn’t interest me. But I thought “Chalkroom” was a more appealing experience because it was all hand-drawn and the rooms were filled with light and your voice and music. In a way, it’s virtual reality but using the oldest of forms, writing and drawing.

LA: Exactly. I didn’t like that visual language, and that’s why I invented this other way to do it. The fact that it’s media is unimportant, you know, in many ways. The most important thing is that these different elements conspire to tell a story.

“I don’t really worry about the philosophical implications of it. I think that would be for somebody else to worry about.”

BM: What are the philosophical or political implications of an experience where the spectator is also the performer, where the writing is constantly erased in the medium of chalk, and where the walls are always collapsing? In a way, one can never really complete a story or come to the end of the experience because everything is always in the process of becoming.

LA: I don’t really worry about the philosophical implications of it. I think that would be for somebody else to worry about. I just try to make really good stories in various media. I don’t really care what the philosophical implications are. I mean, not that that’s not an important question, but it’s not important to me.

BM: What has been the response of spectators at MASS MoCA, where I saw the work, and in other places it’s been installed?

LA: It’s very popular. It’s also been very popular in film festivals. So, it is something that people really respond to.

BM: It won the Venice Film Festival Award for the Best Media Work in 2017.

LA: I think we’re going to put another piece in Venice this year as well. Also, we’re doing something in the Louisiana Museum in the fall about the moon, which I’m really looking forward to.

BM: I know that Danish museum very well. It’s one of my favorite museums in Europe.

LA: That’s my favorite museum in the whole world. So great.

BM: ls there a certain kind of spectator that enjoys this work or that the work might require?

LA: No. I think nine-year-old boys are good at this kind of thing. I think museumgoers and film festivalgoers are getting more used to VR, so they’re getting better at learning the language.

BM: When I experienced the work at MASS MoCA, the first thing I saw was that I was in the clouds, and that made me a bit scared because I felt I was falling. But then I got comfortable after a while with the headset and the goggles and the handheld device. It takes a little time figuring out how to work the device well enough.

LA: It’s a very clunky medium, let’s face it, with the goggles that are too heavy. We did a fifteen-minute cutoff because we think it’s too exhausting for most people to do more than fifteen minutes, although a lot of people do it for a lot longer time. But we tend to make it doable for people. Some people want to bail immediately. It’s just not for them. They get dizzy. It’s not pleasant. So, that’s cool. I mean, I’m not worried about that. It really is a bit of a learning curve.

BM: I stayed in for twenty minutes. I didn’t feel comfortable enough to walk around, but I was very comfortable swiveling in the chair and looking at all the rooms, and eventually drawing, but it was an exhausting experience. Just trying to hold the headset on or trying to grasp being within the VR experience. Is there a beginning and an end?

LA: No, of course, there really isn’t, you know. There’s a little bit of a passive beginning in both things, but then it leaves the viewer to make some choices. In the next work that we’re doing, we’re not giving people as much free rein because I want to make sure it has a bit more of a story structure. I was thinking I would probably be going the other way, but as it turns out, I want to restrict things a bit and give it more structure.

BM: Is that the kind of discovery you made in the piece in terms of narrative strategies?

LA: Yeah.

BM: Next to “Chalkroom” is an exhibit of several of your large drawings, “Lollabelle in the Bardo.” A few years ago, PAJ published your drawings from the performance piece “Delusion.” I’m wondering how you feel about drawing now? How did chalk come to be such a prominent tool in your work?

LA: I love drawing and I love the physicality of doing it. For me, it’s quite a bit like making music, playing the violin. It has a very similar feel to it.

BM: I love drawing, too. I think of it like writing, in a way. I love performance connected to drawing. In “Chalkroom,” even though a lot of the language is words broken apart and there are letters coming at you in all directions, and all the walls are written on, and it’s still an engaging environment. Given where we are in our era and what your interests are — I saw your Town Hall performance in the fall, which had a lot of political commentary — is “Chalkroom” somewhat of a utopian project for you, or going in that direction?

LA: What do you mean, “utopian?”

BM: Is it a new way what we’re more and more going to experience as the world or experience as art?

LA: I don’t know if that has to do with utopia. Do you? It’s a new medium. I don’t know if it’s utopian at all. For me, utopia has something very built-in about a certain kind of optimism about the future. This doesn’t relate to that question, really.

BM: I asked you about utopia because in virtual reality you can create other worlds.

LA: You can do that in painting, you can do that in books. In the moon project that we’re working on now, we’re viewing the moon in all of those aspects of possible dumping ground and possible dream space, just watching different scenarios play out.

BM: You’ve always been interested in science. You were a resident artist at NASA. Where do you think this moon project will go?

LA: Don’t know. Don’t know. I try not to talk too much about what I’m working on.

BM: “Chalkroom” seems to be a very contemporary manifestation of what has been thought of as intermedia. The way it had been envisioned in the 1960s, as the future of art. Do you see yourself extending drawing, writing, storytelling, and music elements, and can virtual reality point the way to a new kind of music and performance form?

LA: Yes, I think it can. But we’ll see. To me, the most important thing is that it’s about disembodiment. I find that in many, many art forms, starting with a novel that you get lost in, starting with a drawing you can get lost in. You can get lost in VR or you can also not get lost in VR. There’s a lot of VR that is very mundane. It just says, “Here you are at the border.” Or, “Here you are in a car lot.” That can also be great as a documentary, but it doesn’t have too much to do with utopia.

BM: MASS MoCA has offered you a home for fifteen years. It has such huge spaces and so many buildings.

LA: Crazy, isn’t it?

BM: Does that encourage you to work on a larger scale?

LA: Not necessarily. It does encourage me to try to come up with more things. I’m not really particularly in that world of exhibitions. Once in a while, I come into the world of galleries and museums. Generally, I’m more interested in music and film and performance. I’m more from the world of theatre, although I’m not a big fan of theatre, I have to say. Anyway, that aside, that’s where I’m normally working.

BM: It’s interesting that even now you have that ambiguity. What is it about theatre that causes you to feel that way?

LA: It was just the way that I like to do theatre, which is not about scripts particularly, and not about stories. I’ve gotten more interested in plays lately, but generally I haven’t been attracted to plays. I was just, I suppose, using a very narrow definition of theatre, and I could have just as easily said, “Well, I like working in dark places, where plays also take place.” Which maybe would’ve been a better way to put it.

BM: I’m curious. You said you’ve gotten interested in plays. Which plays? What kind of plays?

LA: Oh, I mean, just over the years. As a young artist, I might not have gone to a Shakespeare play. Now, I would very, very happily go to one. And the work of contemporary people as well. I found that I’ve gotten over my grudge against theatre.

“I understand that art isn’t real, already. But I thought that the real world was real.”

BM: How do you feel at this time of your life and what do you think is important to do now? Perhaps I can ask it in a different way: Has virtual reality changed your relationship to reality?

LA: I think Donald Trump changed my relationship to reality more than virtual reality did. The second people started chanting “Lock her up,” my sense of reality shifted in a major way. I wish I had more distance and I wish I could just see, “This is really an insane person trying to get attention.” He’s very, very good at what he does. Sometimes I’m kind of lured into his world, even though I recognize it as one of attention-seeking and deeply, deeply disconnected from reality. I still get fooled by it. So, I try not to see it as a disintegrating phase, the last phase of our system. But I would have to say I’m more influenced by his vocabulary of fake news than I am by any art concept of what’s real and what’s not real, or what’s virtual and what’s not virtual, because those things I understand. I understand that art isn’t real, already. But I thought that the real world was real. Silly me, you know?

Bonnie Marranca is Editor and Publisher of PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art.