“Tell Me the Story of This Illness, Please”: Eric Cassell on Truly Hearing Patients

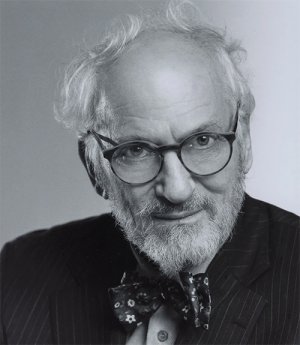

Over three decades ago, the MIT Press was lucky enough to publish a few books by the illustrious physician-writer Eric Cassell. Cassell, who died last month at the age of 93, was a compassionate doctor whose insights, to quote Hastings Center president Mildred Solomon, “have been foundational for many developments in medicine, including the origins of the palliative care movement, patient-centered care, and even disability rights.”

One of those books published by the Press, a groundbreaking two-volume work on doctor-patient communication called “Talking with Patients,” laid the foundation for a humanistic approach to medicine that remained a driving force of Cassell’s work. Combining information drawn from over a thousand hours of tape-recorded conversations between physicians and patients, extensive research into the theories of linguistics, and the personal experiences of his own long career as a clinician, Cassell demonstrates why spoken language is the most important diagnostic and therapeutic tool in medicine. Throughout, he stresses that patients are complex, changing, psychological, social and physical beings whose illnesses are well represented by their own communication.

“I believe there is no other equally effective or realistic manner to approach the study and teaching of communication between doctor and patient in the clinical setting than the use of examples,” writes Cassell in the book’s introduction. “Indeed, the recitation of cases — telling stories — has been a method of teaching aspects of clinical medicine that has survived through the ages because nothing else does the job as well.” The dialogues and accompanying texts featured below are excerpted from the book’s opening chapter.

Eric Cassell’s work, we hope and believe, will continue to inspire healthcare workers for generations to come.

—The Editors

Most students, even most physicians, have never heard someone else take a history from beginning to end. It is sad that even during the period when this crucial technique is being learned, most instructors never listen to their students taking an entire history. The reason usually given for this lapse in teaching is, of course, that the process takes so long. Can you imagine a surgeon saying that surgeons in training are not supervised for a whole operation because it takes too long? Instead of being certain that students fully understand how to carry out this process, one that will be basic to the care of patients for the rest of their lives, we give a couple of “how-to” lectures and let it go at that.

The recitation of cases — telling stories — has been a method of teaching aspects of clinical medicine that has survived through the ages because nothing else does the job as well.

In this chapter you will read many histories and find out what they have in common. The histories appear verbatim, except for two changes. The first is that they have been edited to remove all, or nearly all, the doctors’ questions. What is left is what the patient said before any questions were asked, or what a history would be like if no questions were asked. The second change, for this chapter, is that representations of paralanguage have been removed for ease of reading: the pauses, “urns,” and “uhs” are gone.

Here are the patients’ own words. The first patient is a 54-year-old woman, with thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolus, who was admitted to the hospital as an emergency following this, her first office visit.

All right, tell me the story of this illness, if you would, please.

Well, it started a few weeks ago, I was visiting my sister in Rochester. I wasn’t at home. I was far from home. The first thing that happened was that my eyes swelled up. I’m telling you everything in chronological order. They got kind of black and blue. Now, this has happened before. It’s happened about four times since the beginning of this year. But it seems to be, or so I was told, a contact dermatitis, and possibly unrelated to anything that followed.

Anyway, my sister took me to a friend of hers up there and they seemed to feel that it may have been something I touched or wore and they gave me some Lidex Cream to put on my eye, and then, you know, that hasn’t returned. However, …

But before I was leaving, I think the very next day, still there, I was just sitting at the table and suddenly I got a very bad pain the back of my left leg. About over here. As if maybe a muscle were pulled, or something like that — just ached. A Charlie horse. And then that developed so that within two days I could barely stand on that leg. I thought for a moment maybe it’s something vascular, but my other leg is the bad leg, from the vascular point of view. I had thrombophlebitis in it. That was my good leg.

Anyway, that lasted for about two days and then if l stepped on a stair going up or down, it was very painful. And then that started to subside. But before that subsided, I started getting a sense of pain in two other places. One was abdominally-not cramps really but just a pain, and another was in the middle of the back. I don’t remember which one came first, but the whole procedure has been one thing following another.

I tell you — one thing about the pain. Sometimes I get a spasm, apropos of nothing and it just goes right through. And then last night, for example, I woke up and there’s a spasm, but it seems to be vibrating. The only way I can contain it is by getting into a tub. It’s constricting and —

Right.

And then I had a feeling that it’s going, moving, maybe moving in the direction of the heart.

Right.

And that one —

Isn’t it fearful?

Well, yea — I’m here because last night I really felt fearful.

Mm-hm.

***

What is her chief complaint? A problem with her eyes? Pain in her leg? Chest pain? If you choose chest pain, is it because it is your idea of her chief complaint, or hers? In fact the patient did not give a “chief complaint”; she presented a sequence of events. She is correct when she says, “The whole procedure has been one thing following another.”

Stories, like newspaper reports, have a who, what, where, when, and why.

All histories of illness are stories, and this patient told the physician a story. All stories have certain things in common: they are a series of events that happen to some protagonist in some place over a period of time. Most stories also have reasons: the reason the events described took place. Stories, like newspaper reports, have a who, what, where, when, and why. Here is another story.

Now, tell me the story again, please?

Wednesday evening, we were up at a nice zoo in Tacoma.

Right.

And we went out to a place to have lunch.

Right.

It’s a crazy sandwich place; some kids were running it. And we had lunch, and about three o’clock, two hours after lunch I felt — not cramps exactly but somewhat gripping. Ok, I’ve had a stomach ache for an hour or two before so we walked around and finally I told Judy I wasn’t feeling well, so we go back to the motel. So we go back there then — I’d gone to the bathroom a number of times, two or three times that day. Fine, no problem. And then it seemed to me that the gripping shifted. It wasn’t every minute. It’d go on for a minute or two and then off, minute or two, then it shifted to a lower part.

And the — so I took Super Pectin, a couple teaspoons, tablespoons full, and some Titralac and a couple of Tylenols, ’cause my head was — I guess I was getting scared. And I was very uncomfortable, so we had a heating pad, I put the heating pad on. I got about five to six hours sleep Wednesday night. I had to sleep on my stomach, though. It was the only position I could get comfortable.

Right.

And then, in the morning it persisted. The same thing. A few minutes, then it’ll ease up — but I told you, whatever it was, it worked its way down. But it seems to be centered around here, in the middle of the stomach.

Right.

And it didn’t work its way down. So Thursday morning I spoke to Judy, who said, “The hell with this,” and we caught a flight and, in about eight hours, last night arrived in New York. And this morning, I went to the bathroom just before I came here. It isn’t as bad, but it still occurred even when I was driving in and even for a few seconds in the office.

***

Who are the characters in this story? The narrator is one character. Judy is another. There are the “kids who ran the sandwich place.”

But there is another, much more important character. There is an “it.” The pain is part of the “it,” and so are the other symptoms. “Symptom” is the physician’s name for events that take place because of that character, the “it.” The other unspoken character in this story, to which things are also happening, is the narrator’s body! This is a medical story, an illness story, and illness stories are different from other stories because they almost always have at least two characters to whom things happen. They always have at least a person and that person’s body. It is very important to make the distinction between the person and the person’s body as you hear the history of an illness.

It is essential to distinguish what is occurring in the body from what is happening to the patient, in order to serve the interests of both.

It may be surprising that I seem to be insisting on dividing the person from the body, because I have placed such emphasis on listening to the patient’s personhood and on the contribution of that personhood to the patient’s illness. In fact I do not believe in separating person from body unless it serves a purpose. In history taking, however, it is essential to distinguish what is occurring in the body from what is happening to the patient, in order to serve the interests of both.

This next example displays both the person and the body very distinctly, because the woman is very much a person, and her body is doing some very contrary things.

Two weeks ago, I’m sitting in my office and I start getting these spots in front of my eyes. I couldn’t see anything. I was — you know, nothing. I was just — seeing these little, crazy little spots, which-I’ve had that before, but maybe for a minute, or not even a minute. A couple of seconds or something, I’ll see spots.

So I said, “Well, you know, I’ll stand up, I’ll walk around, it’ll go away. I’ll take out my lenses.” I figured, “It’s the lens —” I wear soft lenses. So I popped out the soft lenses, and the spots didn’t go away so I took a walk and I got as far as the Art Department and I couldn’t well, for one thing I was blind without my lenses and I’m sort of walking like this.

But really it wasn’t just the spots, it was a combination of things. At that point I didn’t really have a headache, I don’t think, I just felt slightly dizzy or something. It was a couple of weeks ago, I don’t remember exactly. But I sat down in there and I was figuring, “Well, what is this?” And I started getting these shooting pains in this side. It was just like all — everywhere. And it just made me a little bit upset. I figured, “Well, I didn’t have anything to eat too much this morning. I’ll go across the street to the Beanery, you know, and get something to eat.”

So I got up from the Art Department and I went down and I was standing on the corner of 52nd Street and Madison Avenue and all of a sudden I just — I guess ’cause I was worried because nothing like this really, I don’t think, ever happened to me — well, I know it didn’t — shooting pains in my head and because I was scared about that, I think this is why this happened, but I felt compelled to hold on to a telametal pole thing, like this, ’cause I started feeling woozy. And then I figured, “Ah, I’m going to get into that place and have some orange juice, and high protein stuff, I’ll feel better.”

Then the light changed and I just — I don’t know what happened. Just sort of, my knees went out from under me. I just fell down and I was carrying my coat, and my coat dropped, so I just went down like this, I got my coat, and I stood up, you know, so that it (I guess) looked to people like I dropped my coat and I just — you know. But really that isn’t what happened. I fell down first.

I go into the place and I say to the guy, “Give me this, this, and this.” And I ordered some stuff and I’m waiting for it — no, I’m sitting there and — it’s sort of getting kind of worse and all of a sudden — and I-I’m-I’m trying to keep sort of in touch. Like I’m saying, “Well, this is all psychosomatic, or something like that. Nothing bad is going to happen.” And then I just sort of freaked out just for a little tiny bit and I just had this horrible image — I had this image that my brains were like bleeding or something. It was very strange. And I just figured, like, “Ah! This is curtains. I’m going to croak. I’m not going to get out of this place!” And I kept thinking, “Isn’t it funny how, I’m sure that people must die of embarrassment. Because I’m in a drugstore, I could have gone — if I was really that scared, I thought I was going to die. I figured, “This must be a hemorrhage or something,” and started thinking of all these things. And I didn’t want to bother the guy in the back to say, “Well, call my doctor,” or something.

And then a little bit after that is — is that I got this headache, like a regular headache, like right in the front, like I’ve had before and it was terrible. But I took some aspirins and stuff, but I was — because I can deal with that. I know what that was. And then it wasn’t until I was OK, I guess. The headache finally went away. It took a couple of hours but the other thing was fine. And I told a friend about this and she said, “Oh! Well, for Christ sake, that was a migraine!” And I thought — I said, “Ah!” (Snap) I mean I didn’t — if l had thought of it when it happened I probably would have felt much better.

***

This story is very clearly told. In one form or another, something like this has happened to all of us. A set of symptoms occur that are very frightening, and then something else happens that clears up the mystery and removes the fear, all in a moment. She is such an articulate patient that we find out not only what happens to her and what she does about it but also her causal thinking. She even describes that most fascinating phenomenon of sick people, that they can “die of embarrassment.” Instead of calling for help, not wanting to bother anyone, people will sit in their car or office and have a heart attack or stroke! She describes these two sets of events — the things — that happen to her and the things that happen to her body (her symptoms) — in a manner that mixes them together. She does not make the distinction between her person and her body, as does the man in the previous example. But it is not necessary that the patient separate body from person in telling the story, only that we do so in hearing it.

Would you have made the diagnosis of migraine headache from the story as told? If you did, you probably have migraine headaches. Do you know what was the matter with the man who returned home from Tacoma? As you probably surmised, he had gastroenteritis. Do we know that because of what he said, or what we (without awareness of our doing it) added to his story as it was told? He gave such sparse information concerning his symptoms that many other diseases could be compatible with those he did describe. If you believe he had food poisoning, it is probably because he mentioned the “crazy sandwich place run by some kids.” In other words, he gave very little concrete evidence on which to base our diagnostic conclusions, providing us instead with his diagnosis, his beliefs about what was the matter and why.

At this point it is quite reasonable to ask what it is that we go after when we make a diagnosis. Is a disease an object like, say, a car? What is gastroenteritis or thromboembolic disease? If l tell you that I have a patient with carcinoma of the breast, you have been told little in terms of taking action. “I have a patient with scirrhous carcinoma of the breast. What should I do?” Before responding, you will need to know the age of the patient, stage of the disease (indeed, a patient may be said to have carcinoma of the breast who had a mastectomy three years earlier and now has no signs of disease), operated or not, size of tumor, number of lymph nodes involved, hormone receptor status, previous treatment, whether the patient lives in a remote area or near a medical center, how much the patient knows about the disease, who I am (surgeon, internist, or oncologist), and more. You cannot even assume the patient is female!

A disease is not a thing, it is a process.

A disease is not a thing, it is a process. A process is characterized by change over time. Events are steps in a process and can be identified in space and time. Just as in a story, events occur over time, so they do in a disease. In other words, not only is the history of an illness a story of events happening to characters through time, but a disease is a story, too. Of course the special name for the story of a disease is its pathophysiology — the unfolding of an abnormal set of events in the body. It might go like this. A person injures the left lower leg, by striking it against something hard. Almost immediately it becomes painful and ecchymotic, but the pain soon subsides.

About 10 days later, another pain develops in the same calf that is different from the original pain, which had by now gone away. The new pain is more achey and sore. Looking down at the leg a day or so later, the person notices that where the ecchymosis had been, there is a place now more swollen and reddish and warm to the touch. After a few more days the ankle is seen to be a bit swollen. Perhaps four days later, while riding in a car, the person gets excruciating pain in the left side of the chest, a little lower than the nipple, which makes breathing very difficult. Within a few more hours the pain is much less severe. But shortness of breath is more prominent, and some staccato coughing accompanies it, occasionally productive of some darkish bloody sputum. By the time the person gets to the emergency room, the pain is gone.

This is the story of thromboembolic disease following an injury. We know, step by step what happened in the body to produce that story. The injury to the vessel wall was followed by the thrombosis, followed by inflammation in the same area, followed by some venous obstruction, after which a piece of thrombus embolized to the lung where infarction took place (the bloody sputum), producing a pleural reaction (thus the pain); as pleural fluid accumulates, the pain goes away. Medical scientists know the story at other levels: macromolecular — involving the clotting process; micromolecular — involving, say, the platelets; the organ level — involving blood vessels and lung. Although we are intensely interested in these other levels, because they provide the basis for our understanding and thus for our actions, we are, at the moment of taking a history, involved only in the whole organism level: How each of the things that happened at every other biological level is reflected in the way the person describes his or her functioning as a whole organism, and that is the on[y level to which we have access while taking a history.

It is a common error for physicians to become confused about which level of human biology we are operating on, at any one time. To reiterate, when taking a history, we are operating only on the whole organism level and are interested only in how malfunctions at any other level are reflected in the functioning of the whole human being! What each physician who cares for patients must develop is the ability to know how dysfunction at other levels — whether it be molecular, cellular, or organ systemic — is expressed at the whole human being level, and just as important, we must learn what a malfunction at the whole human level tells about the state of other levels.

To make the relationship of illness history to pathophysiology even clearer, we should see that there are levels above the whole human that are involved in the story of an illness. It could be that the story of the man from Tacoma starts even before he gets to the restaurant. Pete and Joe are a couple of the “kids” who run the “crazy sandwich place” in Tacoma. Say, a few days before Judy and Jerry went to the restaurant, Pete cut his finger, which became infected. The morning of that day, Pete was making egg salad for the egg salad sandwiches, and Joe told him to put it in the refrigerator and come help out front. Pete forgot to do so (actually he resented Joe always bossing him around), and when Joe returned just before lunch (about five hours later) and saw the egg salad on the counter, he figured Pete had just removed it from the refrigerator, in anticipation of the luncheon rush. Now, Judy and Jerry enter the restaurant and have egg salad sandwiches on whole wheat, and coffee. Six hours later the story of Jerry’s illness starts. These details concerning how staphylococcal food poison is spread are intensely important to not only to epidemiologists, who must concern themselves with social organization and interpersonal relationships, but also to physicians, for whom they provide under standing of the wider contexts of human illness and possible areas in which to take action. But for the physician taking a history the levels of biological systems that are higher than the whole human are only of concern to the degree that they are expressed at the whole organism level.

Eric Cassell (1928–2021) was a distinguished physician, clinical professor, and author who wrote extensively about the intersection of medical practice with ethics, philosophy, and the humanities. This article is excerpted from his two-volume work “Talking with Patients.”