Susan Sontag: A Critic at the Crossroads of Culture

In the late 1960s, very few critics penetrated American middle-class homes like mine, maybe Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, Lionel Trilling, one or two others, but Susan Sontag managed to be among them.

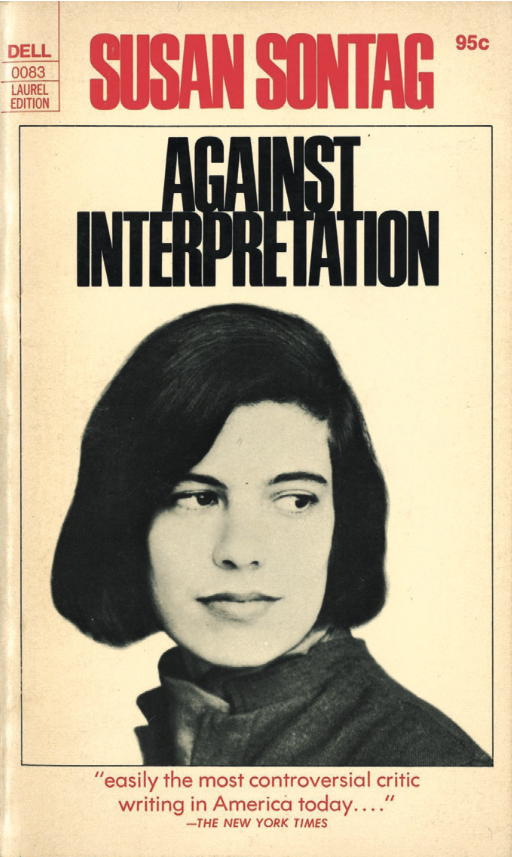

Through a forceful combination of intellect and style, her books found a way into suburban dens where young rebels were in hiding, longing for an artistic culture that might somehow match the political upheaval of the time. Like other restless kids born in the Eisenhower years, I first encountered Sontag through her photograph on “Against Interpretation” (1966), showing a striking woman with short hair swept aside and intense gaze directed elsewhere (it was taken by her friend Peter Hujar). So this, I thought, is what a New York intellectual looks like.

Austere like her prose and engaged like her subjects, Sontag was my first inkling of avant-garde culture, my initial point of access to an edgy alternative to the Anglophonic modernism — Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Joyce — that represented high literature. Her European protagonists — Lukács, Sartre, Camus, Leiris, Artaud, Weil, Sarraute, Pavese, Cioran, Ionesco, Godard, Bresson, Resnais, Bergman — were exotic to me, and the notion that philosophers, writers, and filmmakers could be political was even more so. I didn’t understand the many differences among these figures, but I sensed a shared posture, one that pointed to a way around the given terms of American culture, mass versus elite, and American politics, liberal versus conservative. I, too, wanted to be against. If Sontag could cross over to my living room, maybe I could cross over to her New York downtown (which even then I took to be the name of an elective affinity as much as an actual place), and I was hardly alone in wanting to do so.

It was her combination of lucidity and ambition that made Sontag so attractive; hers was a “style of radical will,” and we didn’t understand then that her emphasis on style might also be her limitation. Certainly, it prepared her critical success, which left Sontag, like other prominent women of her generation, somewhat unmoved by feminist critiques: smart and “serious” (her preferred term of approval) knew no gender for her. As is often remarked, Sontag was a popularizer, but only in part, and if she invented terms that later became clichés, isn’t that what significant critics often do? (Two phrases that qualify in this respect are her plea for “an erotics of art” and her definition of camp as dandyism “in the age of mass culture.”)

So this, I thought, is what a New York intellectual looks like.

A more fitting appellation for Sontag is guide, which she was from beginning to end. Again, she introduced many of us to the figures discussed in “Against Interpretation” and “Styles of Radical Will” (1969), and later she insisted that her New Yorker readers should at least be acquainted with authors like W. G. Sebald and Alexander Kluge.

However, by the time of “On Photography” (1977), “Illness as Metaphor” (1978), and “Under the Sign of Saturn” (1980), we had gained on her. We had read the same authors, often differently, studied others, and worked alternative lines of thought: the Frankfurt School, the different Marxisms of Althusser and Debord, Lacanian psychoanalysis, feminist film theory, deconstruction, discourse analysis, reception theory, and cultural studies. And we had received our reports from other sources as well — journals like New Left Review, New German Critique, October, and Screen — not from venues like her Commentary, Partisan Review, and the New York Review of Books, which remained mostly indifferent if not hostile to such critical work.

Yet this flourishing of theory also made us more sectarian than Sontag was. From first to last, she was a committed generalist, a “master synthesist,” as the New York Times obituary put it. Although she was “against interpretation” in principle, Sontag was always for it in this sense: She believed deeply in her mission to report to interested laypeople about difficult avant-gardes. Today, both sides of this relationship are less clear than they were then, and this difference makes the time of her rise appear distant. But then that very distance might challenge us to renew the vocation of mediator that she served for so long.

Cover of “Against Interpretation.” Photo: Peter Hujar.

Sontag worked to bridge that gap on her own terms. At the same time, in “Notes on ‘Camp’” (1964) and “One Culture and the New Sensibility” (1965), the two texts that made her name, she insisted that other notorious divides — between avant-garde and kitsch and between high and low culture — had narrowed. It wasn’t easy to explain such matters, and sometimes Sontag showed the strain. Some of her arguments are more declared than demonstrated, with an authority claimed through assertion, though this is true of other commentary as well. (Clement Greenberg was expert at this apodictic sort of address, and many critics in the 1960s and ’70s followed suit.) Here, chosen more or less at random, are the first lines of a few essays from “Against Interpretation” and “Styles of Radical Will”:

“The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory.”

“Most serious thought in our time struggles with the feeling of homelessness.”

“A new mode of didacticism has conquered the arts, is indeed the ‘modern’ element in art.”

“Every era has to reinvent the project of ‘spirituality’ for itself.”

“Ours is a time in which every intellectual or artistic or moral event is absorbed by a predatory embrace of consciousness: historicizing.”

These are large claims, and sometimes they float away or pop like balloons. But in a way, that is what they are — trial balloons — and, often enough, they brought back accurate readings of the weather of the time.

Another vaunted term in the Sontag lexicon is “position.” The rush to position, which sometimes seems endemic to criticism, can end up as a posture unless it’s politically grounded. This isn’t to question her commitment to certain causes, which was evidenced by her controversial trips to Hanoi during the Vietnam War and Sarajevo during the Bosnian War; her consistent support of oppressed writers through PEN; and her courageous statements about AIDS, 9/11, and Abu Ghraib. But it is to query how much of it transformed her own production, which was the crucial test for at least one of her favorites, Walter Benjamin.

A common charge is that her seriousness was a matter of aesthetics or ethics more than politics, precisely a style of radical will. And her most engaged piece, “Trip to Hanoi” (1968), is about her own consciousness more than Vietnam, which becomes the scene of a personal disorientation, even though Sontag is also torturously aware of the Orientalism at play in her text. Sometimes she turned the treatment of a problem, political or aesthetic, into an explanation of herself. Moreover, some of her essays on fellow critics contain worries that sound autobiographical: Am I, like Cioran, not original enough? Like Benjamin, too saturnine? Like Barthes, too seduced by sensibility? In “Remembering Barthes,” her moving homage to the great French critic on his death in 1980, Sontag touches on his “self-absorption” and comments that “his interest in you tended to be your interest in him.” One can’t help but wonder the same about her.

But then “self-absorption” was central to her work, to its interest, even to its strength. Her essential method was to replay her thoughts while reading, to dramatize her struggle toward interpretation, and sometimes her shifts in perspective did lead Sontag to rethink and to write again. She could turn her political ambivalence into critical insight (at least since Baudelaire, many important critics, especially when caught between class identifications, have done as much), and so Sontag made good on what Adorno (a critic she didn’t much engage) once called “a flagrant contradiction” — that “the cultural critic is not happy with civilization, to which alone he owes his discontent.”

Beyond critical insight, however, Sontag attempted to push her ambivalence into “passionate partiality,” as she wrote (echoing Baudelaire on criticism) in her preface to “Against Interpretation.” As she also implies there, criticism remained a literary offshoot for her, and sometimes her writing suggests an updated version of the Bildungsroman. This self-absorption could be excessive (when her book of short stories “I, Etcetera” came out in 1978, one heard the plea “less I, more others”), and sometimes Sontag advanced it in default of other grounds on which to work, as she does here in her 1967 essay on Cioran: “The time of new collective visions may well be over. . . . But the need for individual spiritual counsel has never seemed more acute. Sauve qui peut.” No collective vision, everyone for himself, in 1967?

For Sontag, the embrace of popular culture was a testing of high/low divides, a testing that was avant-gardist, not populist.

For these reasons, I balked when the New York Times obituary claimed that Sontag made “a radical break” with the postwar criticism of New York intellectuals, especially those around Partisan Review. Early on, her fondest dream was to write for that journal. Like most of its contributors, she occupied a cosmopolitan territory associated with the academy but not restricted to it (no university presses for her), and she made a living as an independent critic — not easy then and almost impossible now.

More important, though she might challenge particular judgments of Partisan Review writers, her language of evaluation was largely consistent with theirs. Against interpretation, Sontag remained an interpreter; dismissive of the opposition of form and content, she didn’t deconstruct it but valued style where they had valued “substance.” And her other central terms are all old-school: “condition,” “sensibility,” “temperament,” “taste.” “Taste,” she states in “Notes on ‘Camp,’” “governs every free — as opposed to rote — human response.” For good or bad, no one who has passed through Adorno, Althusser, Lacan, Derrida, or Foucault, let alone Bourdieu, could easily write such a sentence. However opposed in principle to “the Matthew Arnold apparatus,” Sontag also argued for “the best that has been thought and known” in culture, as well as for a necessary connection between the aesthetic and the moral — and what could be more Arnoldian than her “seriousness”?

Certainly, her embrace of popular culture irritated some New York intellectuals, for it seemed to undercut their faith in modernism as high culture. Hence, in part, their enormous resentment of the counterculture of the 1960s, which also derided this belief, and their marked shift from liberalism to neoconservatism over that period. Yet for Sontag, the embrace of popular culture was a testing of high/low divides, a testing that was avant-gardist, not populist. Seriousness was always the criterion, even when it was mocked, as in camp; and sophistication was still the goal, even when it concerned the products of entertainment.

Strong signs of her good standing as a New York intellectual (perhaps Sontag was the last of the kind) were the encomia delivered by the New York Times on her death in December 2004 (no less than four articles), in stark contrast, say, to the smear given to Derrida when he died three months before her. Charles McGrath, former editor of the New York Times Book Review, proclaimed her “the preeminent intellectual of our time,” a valuation that depends, of course, on the definition of “intellectual,” let alone of “our time.” The preeminent critic? On this score, she was overshadowed by Barthes, to name just one. The preeminent theorist? That’s not her category.

She also served as a buffer between the two generations, and she was celebrated in part for this compromise position.

One test of intellectual preeminence is whether young critics continue to engage the work, and Sontag isn’t high on reading lists today. Perhaps she’s too New York or “American,” neither “French” nor systematic enough in her thought, nor “German” or philosophical enough, nor “British” or social-historical enough. She didn’t participate in the great rereadings of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, which did in fact produce a “radical break with traditional postwar criticism.” She also didn’t write much about the great adventures of the sign, the psyche, and sexuality that were so formative to “the preeminent intellectuals of our time.” Nor was identity her thing. Perhaps the strength of her work — the focus on European avant-gardes — now appears as its restriction, but she’s not alone there.

In every cultural interregnum, there are a few figures on whom old and new generations can agree. Mahler was one such composer in fin-de-siècle Vienna. Sontag was one such critic in the latter decades of the last century, indulged by old New York intellectuals as a willful prodigy, yet valued by post-1968 intellectuals as a countercultural voice. As such, she also served as a buffer between the two generations, and she was celebrated in part for this compromise position. In this light, Sontag was less a new model of the intellectual than a transitional figure between the critic and the theorist: between the critic, liberal in culture and politics, with one foot in (memories of) the Old Left and one foot in the studio, and the theorist, radical at least in philosophy, with one foot in (memories of) the New Left and one foot in the academy.

Hal Foster is the Townsend Martin Class of 1917 Professor of Art & Archaeology at Princeton University. He co-edits the journal October and is the author of several books, including “Fail Better,” from which this article is adapted. A version of this essay first appeared in Artforum in 2005 and is reprinted here with permission.