Sublime Disasters

John Chapin, an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, was sleeping in a Chicago hotel on October 8, 1871, when awakened by noises in the hallway. He went to the window, “threw open the blinds, and gazed upon a sheet of flame towering one hundred feet above the top of the hotel.” He hastily packed and fled with the other guests into the street “to gaze into the face of the awful but sublime monster that was pursuing me.” Chapin fled toward the Chicago River, and only then realized that the entire city was on fire and that “no human power could stay its progress.” After he was safely across a bridge, he watched the throngs of people escaping with whatever they could carry. Chapin compared the fire to Niagara Falls. “Everyone knows how inadequate is human language to express the grandeur of Niagara — we can only feel it. And yet Niagara sinks into insignificance before that towering wall of whirling, seething, roaring flame, which swept on, on — devouring the most stately and massive stone buildings as though they had been the cardboard playthings of a child.”

The writing on disasters primarily deals with their causes, destructive forces, and human suffering, as well as discussions of who or what was responsible and how to avoid or mitigate future catastrophes. But there is also a sublime aspect to many disasters, as Chapin understood. Both Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke, 18th-century philosophers who contributed significantly to the philosophical discourse on the sublime, recognized that earthquakes, fires, tornados, hurricanes, and floods fascinate anyone who sees them. They, too, can be sublime.

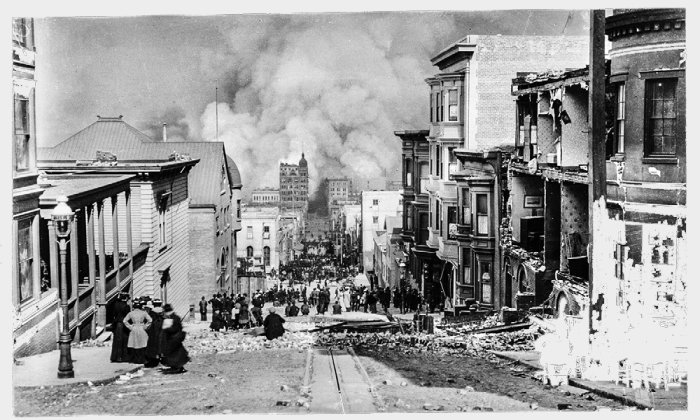

Burke discerned two particular forms of spectacle: dramatic misfortune “before our eyes” and the ruins of historic disasters. Viewing either form of the disastrous sublime, he wrote, “is not an unmixed delight, but blended with no small uneasiness.” This is especially the case when the catastrophe is recent. Disasters call forth immediate pledges of assistance, and this response seems as universal as the sublime itself. In the United States, for example, in 1889, large sums were raised for victims of the Johnstown Flood. Money poured in from American states, Great Britain, Germany, and across Europe all the way to Turkey. A similar outpouring of assistance came to San Francisco after its earthquake and fire of 1906. A century later, when a massive earthquake and tsunami in the Indian Ocean killed an estimated 230,000 people, the public response was unprecedented: More than 10 billion dollars was raised for humanitarian aid and reconstruction efforts.

The sublime response to overwhelming forces can only occur if one is in relative safety and does not fear for one’s life. Like Chapin fleeing his hotel, most of those fleeing the 1871 Chicago fire did not have the margin of safety required to see the conflagration as sublime. But once he was safely across the river, Chapin recognized the fire was an extraordinary spectacle. He was not the only one. William Gallagher, a student at the Chicago Theological Seminary, was awakened by a classmate and told the city was ablaze. When Gallagher went toward the conflagration to help those fleeing with whatever they could carry, he saw few signs of panic. In one prosperous neighborhood, “They were the most philosophical set of people I ever saw. Among those rich people I didn’t see one woman rushing about screaming and [w]ringing her hands. There was no crying or bewailing. The very magnitude of the calamity seemed to overcome all those feelings, and everybody set to work to save what they could.”

Similarly, for some, the San Francisco earthquake evoked less terror than amazement. The Harvard philosopher William James, who was visiting, found it an exciting event. Even when the room was shaking, he reported, “The emotion consisted wholly of glee and admiration.” He later declared he would not have missed it for anything. Many were excited, even ebullient.

One did not need to experience a catastrophe directly to appreciate the disastrous sublime, which was ancient as well as modern.

Kevin Rozario has argued that the “enthusiasm for disasters was . . . a crucial ingredient of the modernizing process.” A “culture of calamity,” he writes in his book of the same title, became an imaginative counterpart to a “social order governed by processes of creative destruction.” Viewing ruins of disaster was part of this process. When viewing the broken walls and isolated columns of Chicago in 1871 and San Francisco in 1906 in the aftermath of disaster, or the flood-smashed remains of Johnstown, reporters almost invariably asserted that the will of the people was unbroken and that a new, improved city would rise from the wreckage. Harper’s Weekly printed a drawing of the first structure erected on the ruins of Chicago: a rough wooden shanty. The sign above the door declared: “All gone but wife, children and energy.” This was not an isolated case of bravado. The city’s boosters declared that the fire created unprecedented opportunities for investment, and the Chicago Tribune editorialized under the headline “Chicago Shall Rise Again.” Some even saw the fire as a purification, preparing the city for a central role on the world’s stage.

Photographs of ruins circulated widely, including those of Richmond, Virginia, at the end of the Civil War; Chicago in 1871; and central Johnstown in 1889 where the flood, writes the historian David McCullough in his book on the disaster, had utterly demolished more than 1,600 buildings, and it was all but impossible even to discern the pattern of the streets. Until the 1880s, professionals took most of the photos, but the democratization of image-making came quickly after that, with the introduction of dry plates, roll film, and Kodak cameras.

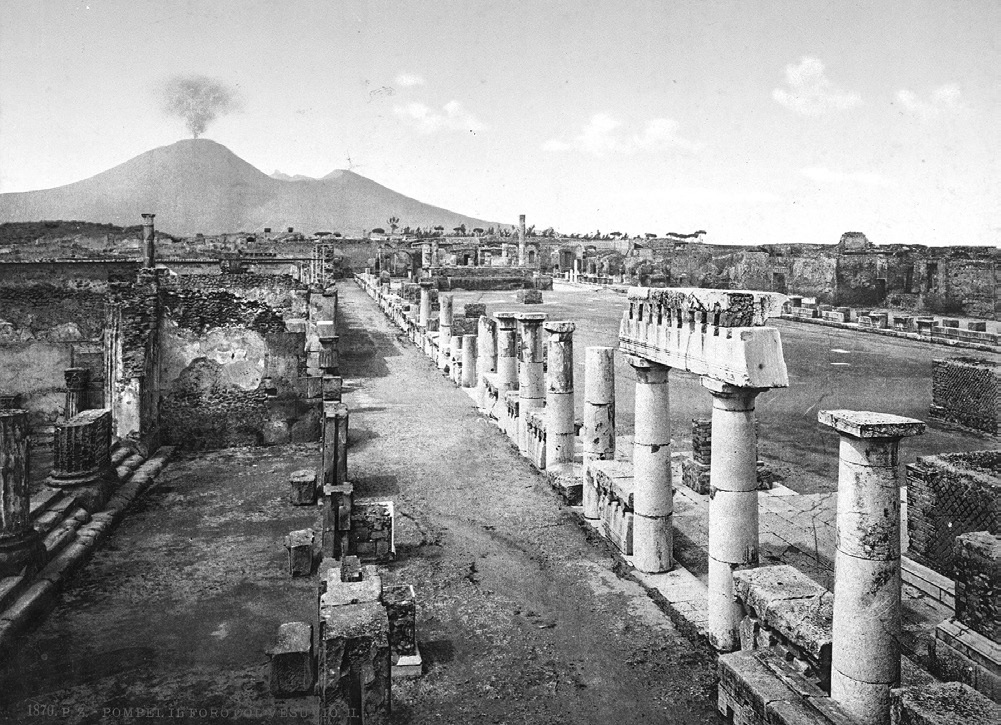

One did not need to experience a catastrophe directly to appreciate the disastrous sublime, which was ancient as well as modern. A prime example is Pompeii, a Roman city buried by a volcanic eruption. In 79 AD a dense cloud of hot pumice, rocks, and fine ashes fell over the city for 18 hours, collapsing roofs and burying the population under 10 feet of debris. The following day, surges of hot gas and pumice swept down the mountain, including two waves of at least 200 degrees Fahrenheit that covered Pompeii with another meter of rubble. No one in the town survived. It remained buried until excavations began between 1748 and 1754. They aroused interest across Europe. One anonymous writer then observed that “empires, however firmly founded, and that cities, however embellished, are like man, subject to mortality, and liable to dissolution. This thought naturally humbles the mind in the dust, and we learn to know our own insignificance, the vanity of our pretensions, and the futility of all earthly glories.” These thoughts on the insignificance of the individual in the larger scheme of history constitute the moral lesson the disastrous sublime was expected to teach. The framework for contemplating Pompeii when its ruins were opened to the public included all the elements necessary to evoke a sublime response: the irresistible dynamic power of nature, a long historical perspective, and the weakness of humanity.

During the 19th century, the tide of tourism grew, stimulated by improved transport, the publication of guides, and the rise of the Thomas Cook agency and other travel bureaus. Those unable to visit Pompeii could see its destruction recreated in dramatic performances. In Britain, the impresario James Pain staged “The Last Days of Pompeii” and then brought it to Manhattan Beach in 1879, well before Coney Island had developed its multiple amusement parks. The sensational effects of Pain’s show filled grandstands that seated 10,000 people, and it ran every summer until 1914, even though the Dreamland amusement park constructed a second show about Pompeii in 1904. Pompeii was regularly destroyed in 30 American cities.

As Burke knew, disasters excite the passions and arouse immediate sympathy. Simulations of disasters were common attractions at world’s fairs and in amusement parks, including some notorious technological failures.

One of the worst was the dam that collapsed and released a wall of water that smashed through the city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, carrying everything in its path to a stone bridge where desperate survivors were trapped amid broken houses and a great accumulation of debris until the whole mass caught fire, adding a deadly conflagration to the devastation of the city upstream. The Johnstown Flood dominated news headlines for a week and was reenacted at amusement parks for a generation. Coney Island, for example, restaged the Johnstown Flood many times a day for several years, according to John Manbeck. After the 1900 Galveston Hurricane killed between 6,000 and 10,000 people and destroyed most of that city, Coney Island also recreated that disaster starting in 1902. This show proved so popular that it was restaged on “The Pike” at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 in a structure built for the purpose that cost $60,000. The Galveston Hurricane was also staged in Boston, Columbus, Indianapolis, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Kansas City.

Crowds paid to see recreations of disastrous floods and fires at amusement parks, and to see staged head-on railroad collisions between steam locomotives. At one such event in 1896 the crash could be “heard for miles and the air was filled with debris. Both engines sprang into the air and held each other by the nose, while the cars piled up behind them. The wreck was perfect. The locomotives remained forming a perfect Y and all the cars were telescoped. The air was filled with steam and hot water and 25,000 people were panic stricken. When the air cleared and the wreck could be seen, a cheer went up from 25,000 throats.”

Crowds paid to see recreations of disastrous floods and fires at amusement parks, and to see staged head-on railroad collisions between steam locomotives.

Lauren Rabinovitz’s “Electric Dreamland” presents the culture of disasters as a part of the coevolution of American amusement parks and cinema. “By 1910,” she writes, “every municipality with a population of more than 20,000 had both amusement parks and motion picture theaters.” The parks and theaters recreated disasters that taught Americans to anticipate and even enjoy dangerous events, such as wrecks, floods, or fires. The disastrous sublime offered by amusement parks was a psychological experience that included not just sights but also sounds, winds, and smells that created a powerful simulation of disaster, viewed in comfortable seating. By comparison, early cinema offered only silent black-and-white images with musical accompaniment.

Temporary toxicity may also be sublime. In Don DeLillo’s “White Noise,” the main characters must evacuate their home because of an airborne toxic event caused by leaking chemicals. There are three stages to this experience. The first is denial that such a thing can be happening at all. Next comes exposure to the event itself — an enormous, toxic black mass. Yet confronting this cloud of death “was also spectacular, part of the grandeur of a sweeping event,” and their “fear was accompanied by a sense of awe that bordered on the religious.” Those who viewed the Great Chicago Fire or who lived through the Great San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906 felt something similar. Like DeLillo’s protagonists, they recognized that it is “possible to be awed by the thing that threatens your life, to see it as a cosmic force, so much larger than yourself, more powerful, created by elemental and willful rhythms.” The experience of a simulated apocalypse or of an anti-landscape is a staple of the film industry. Barry Langford has observed that screened apocalypses “are enjoyable rather than horrifying because they are fantasy: in fact, because the technological capacity to deliver a photo-realist simulation of the end of the world reassures us of technology’s ability to contain by imagining and acting out any threat, however final and non-negotiable.”

There is widespread interest in apocalyptic landscapes. Edward Burtynsky’s photographs of waste and pollution draw crowds to exhibitions. There are tours to Nevada’s atomic testing site, and tourists pay guides to lead them into Chernobyl’s radioactive zone. Some seek only the thrill of viewing a fatal landscape, but others want to intensify their environmental awareness, and they expect their guide to provide an educational experience. The fascination with comprehensive devastation culminates in visits to environments that cannot sustain human life — and these are often portrayed in books and films depicting a near future where most of humanity has been wiped out. Cormac McCarthy’s novel “The Road” is a prominent example. The imagination of future ruins is not new. As the writer Miles Orvell demonstrates in “Empire of Ruins,” it can be traced back at least to the 18th century, including dramatic paintings and photographs as well as fiction, in each case depicting fragments of the present that survive into a dark future. The attraction of this trope seems to be intensifying in the Anthropocene.

The natural sublime of the 18th century understood disasters as a terrible and inscrutable “act of God.” The technological sublime of the modernist period presented engineering works as bulwarks against disaster, like the seawall constructed around Galveston. But what form of the sublime is possible in the Anthropocene?

One can focus too much on spectacular disasters like the bursting dam that destroyed Johnstown, and miss another sort of disaster, when a new megadam slowly inundates a fertile river valley, destroying its ecology and its farming communities. Rob Nixon, in his book “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor,” argues that megadams in India have produced “developmental refugees” who are rendered invisible by the rhetoric of progress, globalization, and hydroelectric modernity. Anthropologist Thayer Scrudder has estimated that during the 20th century large dam projects displaced between 30 and 60 million people. They have been written out of the script of progress and become “uninhabitants.” Dams more than 50 feet high did not exist until the 20th century, when 36,562 were built. Hoover Dam was the exemplar of this movement. It combined “practical purpose and aesthetic ideals by marrying a miraculous feat of American engineering to a sublime spectacle of grandeur,” writes Nixon. These “megadams became places where the transcendentalisms of religion, nation, science, and art would converge.” The grandeur of large dams was connected to the idea of progress in various parts of the world, including communist nations like the Soviet Union, capitalist nations like the United States, or the postcolonial societies of developing nations. These enormous structures became secular temples symbolizing the conquest of nature.

On the one hand, the technological sublime may function as a form of false consciousness, drawing attention away from the devastating effects of large engineering projects. On the other hand, the sublime may also be the intended experience of an artwork that draws attention to global warming or species extinction caused by millions of consumer decisions that collectively have unintended consequences: polluted water supplies, islands of discarded plastic in the world’s oceans, or the melting of polar ice caps. The technological sublime can become an ideological mask hiding disaster, but it can also be transformed in art to call attention to the slow violence of the disastrous sublime.

These quite different possibilities are particularly evident with atomic technologies. Nuclear bombs did not elicit pride in human achievements, but rather, dread. After Hiroshima, there was an uneasy oscillation between fear of a nuclear holocaust and the hope that nuclear power could provide limitless energy. As nuclear weapons proliferated, however, a new conception of infrastructures emerged that saw cities not in terms of the mastery of nature but rather in terms of vulnerability and ruin. Resilience may come from the public’s improvisation to overcome system failures. In an apocalypse, however, there is no safe place where one can experience the sublime. Infrastructure would fail permanently, everyone would be a victim, and there would be no one outside the apocalypse left to help. (In contrast, when viewing the simulations of apocalyptic films, the public are surrogate outsiders, witnessing destruction in safety.)

To the extent that we recognize our complicity, we are horrified, uneasy, and yet attracted when faced with disasters, even more than Burke was centuries ago.

Edmund Burke observed that disasters are often experienced indirectly, through newspapers, art, or other representations, and that is even more true today, when catastrophes are front-page news. It is also still the case, as Kant noted, that all sublime experiences can be divided into encounters with either with dynamic spectacles or overwhelming immensities. The disastrous sublime may be either a directly experienced spectacle such as the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, or a landscape seen long after the fact, such as the ruins of Pompeii. Sublime landscapes are quiet or even silent scenes of death and destruction, such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina or Chernobyl after the nuclear meltdown. In contrast, disastrous sublime spectacles such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, fires, and hurricanes are ephemeral, loud, active, and immediately dangerous. To experience them, one has to be near the volcano when it erupts, on the coast when the hurricane hits, or in the city during the firestorm. The dynamic sublime rivets terrified attention on immediate threats, such as shrieking winds, airborne debris, fire, or unpredictable aftershocks. One stands outside of sublime ruins and gazes at them; but sublime spectacles immerse all the senses and temporarily obliterate both past and future.

Until the 19th century, disasters were generally thought to be “acts of God.” Their awful sublimity was part of an inscrutable destiny. Why some survived and others died seemed a quirk of fate. As humanity’s powers increased, disasters have kept pace in both speed and scale. Technological triumphs such as dams, bridges, or airplanes could become wrecks or ruins, sublime both at their inception and in their demise. During the 20th century, human agency began to be accepted as a partial cause of such disasters. And to the extent that we recognize our complicity, we are horrified, uneasy, and yet attracted when faced with disasters, even more than Burke was centuries ago. The sense of human responsibility for catastrophes intensifies when contemplating the other new forms of sublimity evoked by modern warfare, environmental destruction, and the Anthropocene. The disastrous sublime is part of an evolution in sensibility occurring in tandem with growing human powers and increasingly destructive forces.

David E. Nye is Senior Research Fellow at the University of Minnesota’s Charles Babbage Institute and Professor Emeritus of American Studies at the University of Southern Denmark. Nye is the author of numerous books with the MIT Press, including “American Technological Sublime,” “Conflicted American Landscapes,” and “Seven Sublimes,” from which this article is adapted.