Stanisław Lem's Reflections on the Objects of His Childhood Home

We lived in six rooms, yet, with all this space, I didn’t have my own. Next to the kitchen was a room that had a bathroom behind a door painted the same color as the wall, an old couch, an ugly cabinet, and under the window ledge a cupboard where Mother stored food. Then there was a hall, the door to the dining room, my father’s study, and my parents’ bedroom. Special doors led to the off-limits area: the patients’ waiting room and my father’s office. In our apartment I lived everywhere and belonged nowhere.

First I slept with my parents, then on a couch in the dining room. I tried to settle in one place permanently, but somehow it never worked out. When the weather was warm, I would occupy a small concrete balcony off my father’s study. From this outpost I would attack the surrounding buildings, because their smoking chimneys turned into enemy warships. I also liked to be Robinson Crusoe, or, rather, myself, on a desert island. As far back as I can remember, I was intensely interested in eating, so my major concern as a castaway was to secure food — paper cones filled with shelled corn or beans, and, when in season, cherries, whose pits also served as ammunition for small arms or simply to squeeze with your fingers. Sometimes I replenished my supplies with coffee grounds or dessert leftovers stolen from the dinner table. I would surround myself with saucers, bags, and cones, and begin the difficult and perilous life of a hermit. A sinner, even a criminal, I had much to brood over and ponder.

I learned how to break into the middle drawer of my mother’s dining-room cupboard, where she kept the cakes and pies; I would remove the top drawer and with a knife cut off a thin strip from around the edge of the cake so that no one would notice that it was smaller. Then I gathered and ate the pieces, and carefully licked the knife clean to cover my tracks. Sometimes caution struggled with lust within me for the candied fruit the bakers used to embellish their creations. More than once I could not control myself and robbed the crust of the candied orange, lemon, and melon rinds that squeaked so deliciously between my teeth. Thus I made bald spots impossible to conceal. Afterward, I would await the consequences of my act with a mixture of despair and stoic resignation.

The witnesses to my balcony adventures were two oleanders in large wooden tubs, one white and one pink. I lived with them on terms of neutrality; their presence neither pleased nor bothered me. Inside, there were also plants, distant and stunted relatives of the flora of the south: a rusty palm that kept dying but could not give up the ghost entirely, a philodendron with shiny leaves, and a tiny pine, or maybe it was a fir, which once a year produced clusters of fragrant, young, pale-green needles.

In the bedroom were two things that fed my earliest imaginings: the ceiling and a large iron chest. Lying on my back when I was very small, I would look at the ceiling, at its plaster relief of oak leaves and, between the leaves, bumps of acorns. Drifting into sleep, I thought about these acorns. They occupied an important place in my mental life. I wanted to pick them, but not really, as if I understood, even at that age, that the intensity of a wish is more important than its fulfillment. Something of this infant mysticism passed to real, ordinary acorns; removing their caps seemed to me, for years, a portentous thing, a kind of transformation. My attempt to explain how important this was to me — it is probably in vain.

“In the bed in which I slept, my grandparents died.”

In the bed in which I slept, my grandparents died. It was Grandfather who left the iron chest, a large, heavy, useless object, a kind of family strongbox from the days before professional safecrackers, when robbers used nothing more sophisticated than a club or a crowbar. The chest, always placed against the door between my parents’ bedroom and the waiting room, had flexible handles, a flat lid with flowers carved in it, and in the center a square piece which, when pressed on the side in the right way, popped open to reveal a keyhole. Such cunning today seems touchingly naive, but at the time I thought the black chest was the work of a master craftsman. And I was in complete awe of the key itself, as big as my forearm. I had to wait a long time, impatiently, to grow until the moment when, using both hands and superhuman effort, I was able to turn that key in the lock.

I knew of course that there was no treasure in the chest. What lay at the bottom were a few yellowed newspapers, documents, and a wooden box filled with beautiful thousand-mark notes. I played with this money, and with the cheerful blue hundred-ruble notes, too, which were even more beautiful than the marks, whose brownish color brought to mind dingy wallpaper. There was an incomprehensible story behind the money, something that had suddenly taken away its power. If I had not been allowed to do with the notes as I pleased, I might have thought that some of their power — asserted by ciphers, seals, watermarks, and oval portraits of men in crowns and beards — remained in them and was only slumbering. But since I was allowed to play with them, I had contempt for them, as one has contempt for a splendid thing that turns out to be empty of truth. So I could not rely on the notes for excitement, but only on what might take place inside the black chest when it was long locked — and it was almost always locked, with my silent permission, which of course no one asked me for. Yes, in that darkness inside, something could take place. That was why the opening of the chest was a matter of great weight — literally, too, since the lid was tremendously heavy. From three sides came long bars, and you had to lift them and prop them with a series of special levers; otherwise, I was told, and I believed it, the lid, falling, could chop off a head. Which was what you would expect from such a chest. It was not pretty or pleasant; a gloomy, ungainly thing; yet I long relied on its inner strength. It had a row of holes in its bottom, so the chest could be bolted tight to the floor; an excellent idea. But there were no bolts, none needed now. As time passed, the chest was covered with an old rug and thus reduced to the level of everyday household furniture. Humbled, it no longer counted. On occasion I showed one of my friends the key — it could have been the key to the city gates. But the key got lost somewhere.

Beyond the bedroom was my father’s study, which had a big bookcase enclosed in glass, big leather armchairs, and a small round table with curious legs that resembled caryatids, because at the top of each was a little metal head. At the bottom, little bare feet, also metal, stuck out of the wood as if out of a coffin. Which didn’t seem at all grotesque to me, too young to make such associations. I proceeded systematically to gouge out all the heads, one after another, and found that they were hollow bronze. When I tried to put them back, they buckled with every movement of the tabletop.

My father’s desk, covered with green cloth, stood against the wall by itself and was locked, for it held money: real money. On rare occasions the desk would also store more valuable treasure, more valuable from my point of view then — a box of Lardelli chocolates brought all the way from Warsaw, or a box of candied fruit. My father had to fiddle with a cluster of keys before one of those morsels, rationed out like medicine, would finally appear before me. At which point I was torn between opposite desires: I could either consume the delicacy immediately or prolong the anticipation of its consumption as much as possible. As a rule I ate everything at once.

“I believed, not confiding this to anyone, that inanimate objects were no less fallible than people. They, too, could be forgetful.”

Also locked in that desk were two objects of great beauty. One was a tiny wind-up bird in a box inlaid with mother-of-pearl, which they said came from the Eastern Fair and had been on exhibit there, a thing not for sale. My father, seeing how the pearl lid opened when you pressed a miniature key, which revealed another lid, one with a golden checkerboard, and how from there jumped a bird smaller than a fingernail, all iridescent and flapping its wings and poking its beak and flashing its eyes, and how it strutted in a circle and sang — seeing this, he set in motion a whole army of stratagems and connections and finally purchased this jewel for an astronomical sum. The bird was taken out and turned on only rarely — so I wouldn’t get my hands on it, which would surely have meant the end of the little thing. Although I loved and revered it no less than did my father, I could not control myself. For a while there was another bird that stayed in the desk, one less fine, the size of a sparrow, a wind-up that had no musical ability but only pecked the table vigorously when you put it there. I persuaded my father to let me have it longer, and that was its last hour.

There were little knickknacks, too, in my father’s desk. I remember best the eyeglasses no larger than a matchstick, with gold wire frames and ruby lenses, which sat in a gold etui. The less valuable knickknacks were kept in the glass case in the dining room. These were all works of the miniaturizer’s art — a table with chessboard and chessmen fixed in place forever, a chicken coop with chickens, a violin (from which I pulled the strings), and assorted pieces of ivory, furniture, and an egg that opened to reveal a group of figures packed together. Also silver fish constructed of tin segments which allowed for movement, and bronze armchairs, each seat the size of a fingertip, upholstered with the softest satin. Somehow — I do not know how — most of these objects survived the years of my childhood presence.

My father’s study had old, big armchairs, and the narrow but deep crevices between their cushions and backs slowly gathered a variety of objects — coins, a nail file, a spoon, a comb. I labored mightily, straining my fingers and the chairs’ springs, which twanged in pained protest, to retrieve all these, breathing the smell of old leather and glue. Yet it was not such objects that spurred me on but, rather, the vague hope of finding — hatched — objects altogether different and possessing inexplicable qualities. This is why I had to be alone when with quiet fury I set about disturbing those lazy things dark with age. The fact that I found nothing out of the ordinary did not cool my ardor.

But here I should acquaint the reader with the basic principles of the mythology I adhered to then. I believed, not confiding this to anyone, that inanimate objects were no less fallible than people. They, too, could be forgetful. And if you had enough patience, you could catch them by surprise, forcing them to multiply, among other things. Because a penknife kept in a drawer, for example, could forget where it belonged, and you might find it someplace altogether different, between books on a bookshelf, say. The penknife, unable to get back to the drawer in time, would have no choice in such a situation but to duplicate itself, so there would be two of them. I believed that inanimate objects were subject to logic and had to abide by definite rules, and whoever knew those rules could control matter. In an obscure, almost reflexive way I held on to this faith for years — and cannot say I am completely free of it even now.

The library, because it was locked, fascinated me. It contained my father’s medical books, anatomical atlases, and, thanks to his absentmindedness, I was able to inform myself in a systematic and thorough way about the differences between the sexes. But, oddly, I was far more impressed by the volumes on osteology. The blood-red or brick-red plates showing men with their skin peeled off like raw steak disgusted me; the skeletons, on the other hand, were so clean. I don’t know how old I was when I first thumbed through the heavy black quarto tomes with their yellow drawings of skulls, ribs, pelvises, and shins. In any case I had no fear of those corpses, nor did the study of them give me any squeamish pleasure. It was, instead, like going through a catalog of Erector-set parts, where first we see the individual shafts, levers, and wheels, and then on following pages constructions that can be made from them. It is possible that these osteological atlases appealed to my interest in building things, which did not show itself until later. I thumbed through those books conscientiously, and remember some of the illustrations to this day — the bones of the foot, for example, tied together by ligaments drawn in sky blue, probably for contrast.

Since my father was a laryngologist, most of the thick volumes in his library dealt with diseases of the ears, nose, and throat. These organs and their afflictions I privately considered of little importance, a prejudice I did not realize I had until recently. Prominent in the collection was the monumental dozen-volume German Handbuch of otolaryngology. Each volume had no fewer than a thousand glossy pages. There I could look at heads cut open in various ways, innumerable ways, the whole machinery drawn and colored with the utmost precision. I especially loved the pictures of brains, whose different coils were distinguished by every color of the rainbow. Many years later, when in an anatomy lab I saw a real brain for the first time, I was surprised (though of course I knew better) that it was so drab a thing.

“I sat like a rider on the large squeaky leather arm of the armchair, hidden from the door by the doors of the open bookcase, open so I could quickly put the book back in its place.”

Since these anatomical sessions were forbidden, I had to plan them carefully. Such tactical preparation is by no means the privilege only of adults — provided a child is sufficiently motivated. I sat like a rider on the large squeaky leather arm of the armchair, hidden from the door by the doors of the open bookcase, open so I could quickly put the book back in its place. I rested the book against the back of the chair and in that position continued my studying. It is curious, what I thought at the time. I was drawn by the purity and precision of the illustrations. Again, I was to experience disappointment when many years later, as a medical student, I realized that what I had seen in my father’s study were only idealizations, abstractions, of the systems of nerves and muscles. Nor can I recall ever feeling that there was any connection between what I saw in the books and my own body. There was nothing disturbing in those plates — perhaps because of their matter-of-factness, the breaking up into parts, and the fanatical completeness, which showed not only anatomical detail but even the fingers and hooks used to part the cut skin for better viewing. There were other books there also, with illustrations indeed frightful, but too frightful for me to fear them either. These showed wounds of the face, in war: faces without noses, without jaws, without earlobes or eyes, and even faces that were without a face, being only a pair of eyes among scars, with an expression that said nothing to me, for I had nothing with which to compare it. I might have shuddered a little, but only as you shudder listening to a fairy tale. In fairy tales, awful things happen, in fact are expected to happen, and the shudder is desirable and pleasant. And many things in those books were funny: artificial limbs, artificial noses attached to eyeglasses, artificial ears on headbands, little masks that smiled, clever plugs to fill holes in cheeks, and false teeth and palates. All this seemed to me a masquerade grown-ups played, a little mystifying, like so many of their games, but containing nothing bad or shameful. There was only one thing, not a book, that made me uneasy. It lay on one of the shelves, in front of the gilded spines of thick tomes: a bone, a temporal bone removed by surgery of the middle ear, by a mastoidectomy. I knew only that it was a bone, similar in weight and touch to the bones sometimes found at the bottom of a bowl of soup. On the shelf, as if set there on purpose, it alarmed me a little. It had a definite smell, mostly of dust and old books, but with a whiff of something else, sweetish, rotten. Sometimes I would take long sniffs of it to figure out what it was, as if smell was the sense that led me. Then at last I would feel a slight revulsion and put the bone back, making sure it lay exactly in the same place.

The lower shelves were filled with stacks of French paperbacks, frayed, torn, and without covers, as well as some magazines — one was called Uhu and was in German. The fact that I could read titles doesn’t help establish the time of this memory, since I could read from the age of four. I would leaf through the crumbling French novels because they had amusing fin-de-siècle illustrations. The texts must have been spicy, though this is a present-day conclusion, a reconstruction based on memories half-effaced by the passage of time.

On some pages there were ladies in elegant dignified poses, but several pages later the dignity was suddenly replaced by lace underwear, a man escaping through a window and losing his pants while ladies in long black stockings and nothing else were running around the room. I see now that the proximity of these two kinds of books was peculiar, and the way, too, that I leafed through everything, straddling the armchair as I went, without concern or hesitation, from skeletons to erotic nonsense. I accepted, as one accepts the clouds and trees. I was learning about the world, accustoming myself to it, and found nothing dissonant in it.

On the bottom shelf was a metal tube, wider at one end, and in it was a scroll of unusually thick, yellowish paper. Attached to the scroll, a black-and-yellow twisted cord led to a small flat canister that contained something resembling a tiny bright-red pastry with writing in high relief. This was my father’s medical diploma, on parchment, beginning with the enormous, lofty words Summis Auspiciis Imperatoris Ac Regis Francisci Iosephi. The tiny pastry — into which I gingerly tried to sink my teeth once or twice, but no more, because it didn’t taste good — was the grand seal, wax, of the University of Lvov. I knew that the tube contained a diploma because my father told me so, but I had no idea what a diploma was. I was also told not to pull it out of the tube, and that parchment was made from donkey hide, which I didn’t believe. Later I was able to read a few words, though not understanding anything. It was only in my first year of gymnasium, I believe, that I could make sense of those lofty words.

This example of the diploma illustrates the process of the repeated updating of our knowledge of objects and phenomena. I went gradually from level to level, each time learning the next version of the thing, and in this there was nothing remarkable. Everyone knows it — everyone first learned the version of the stork and then the more realistic explanation of his own genesis. The point is that all the earlier versions, even those as patently false as the one with the stork, are not discarded completely. Something of them remains in us; they mesh with succeeding versions and somehow continue to exist — but that is not all. As far as the facts are concerned — say, in the case of my father’s diploma — it is not difficult to determine what the correct version is, the one that counts. It is otherwise with experience. Each experience has its weight, its authority, which does not admit of argument and depends only on itself. And herein lies the problem, for the sole guardian and guarantor of the authenticity of experience is memory. True, you can say that there are “doubtful” experiences, on the order of my fantasizing about the black iron chest. But it is not always possible to make such a categorical judgment.

“Each experience has its weight, its authority, which does not admit of argument and depends only on itself.”

To the side in my father’s bookcase was a row of tightly packed books which I left alone, having found that they had no pictures. I remember the color and weight of some of them, nothing more. I would give a great deal now to know what my father kept there, what he read, but the library was swallowed whole by the chaos of war, and so much happened afterward that I never asked. And thus the child’s version — primitive, false, really no version at all — remains the final one for me, and this applies not only to those books but also to a multitude of things, some of them dramatic, which were played out over my head. Any attempt of mine to reconstruct them, using logic and guesswork, would be a risky enterprise indeed, perhaps a fantasy, moreover a fantasy spun not by a child. So I think I had better not.

The dining room, as I mentioned before, contained, besides the usual set of chairs and a table that opened for larger groups, a very important cupboard, the abode of desserts, with the shelf where Mother kept the “nips,” her specialty. Near the window was a fluffy rug on which I loved to sprawl while reading book — now my own books. But because the act of reading was too passive, too simple, I would rest a chair leg on my calf or knee or foot and with little movements keep the chair at the very brink of falling. Sometimes I would have to stop in midsentence to catch the chair to avoid the noise that would call the household’s attention to me, which I didn’t want. But I’m getting ahead of myself, always a problem in this kind of account.

As far back as I can remember, I was frequently ill. Various quinsies and flus put me in bed, and generally that was a time of great privileges. The whole world revolved around me, and my father asked me in detail how I felt, establishing between us certain passwords and signs which would describe how I felt with incredible precision, to infinitesimal degrees on a scale that didn’t exist. I was also the object of complicated procedures, some not exactly pleasant, such as drinking hot milk with butter. But inhaling vapor was great entertainment. First a large washbasin full of hot water was brought in, and Father would add an oily liquid from a bottle with a worn cork. Then he went to the kitchen, where a cast-iron lid was being heated over the flames. He brought it in, red hot, with a pair of tongs and put it in the basin, and my job was to breathe in the aromatic steam. It was a wonderful spectacle, the furiously boiling water, the hissing cherry-red iron, blackened flakes of it falling off, and in addition I got to float things in the basin, whatever was in reach, a toy duck, a wooden pen box. I hope I did not fake pain I did not feel. There must have been the temptation to do this, since my father could not refuse me anything when I was sick. The bird in the mother-of-pearl box sang for me then, and I was allowed to play with the gold eyeglasses with the ruby lenses, and when my father came home from the hospital, he brought “packies” filled with toys. Illness was certainly profitable. Thanks to a sore throat I got a wooden limousine large enough for me to ride sitting astride its roof. There were illnesses, of course, like the stone in my bladder; the pain and fever from that made all gifts and games inadequate compensation. Yet one way or another I always returned to health.

“When I was well, I would spend a lot of time by myself. I explored our apartment on all fours, since being a beast increased my sense of smell.”

When I was well, I would spend a lot of time by myself. I explored our apartment on all fours, since being a beast increased my sense of smell. So seriously did I take this animal impersonation that I developed thick calluses on my knees, and had them even in the higher grades of elementary school.

It is time now to talk about my nasty side. I ruined all my toys. Possibly my most shameful deed was the destruction of a lovely little music box of shiny wood, in which under a glass lid little golden wheels with spokes turned a brass cylinder that made crystalline music. I was not to enjoy this marvel for long. I got up in the middle of the night, apparently decided, because I didn’t hesitate at all, lifted the glass lid, and peed into the works. I couldn’t explain later to the alarmed household what had prompted this nihilistic act. A Freudian psychologist, I am sure, would have labeled me with some appropriate terminology. In any case, I grieved over the silencing of that music box no less sincerely than many a rapist-murderer has grieved over his freshly slain victim.

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. I had a little miller who, when you wound him up, would carry a sack of flour up a ladder to a storeroom, descend for another, carry it up, and so on, endlessly, because the sacks thrown in the storeroom meanwhile traveled back down to the foot of the ladder. I had a man in a diving suit inside a jar sealed with rubber, which, when pressed, would send the diver deeper into the water. I had birds that pecked, carousels that turned, racing cars, dolls that did somersaults, and I disemboweled them all, without mercy, pulling wheels and springs out from under the bright paint. For my magic lantern made by Pathé, with the enameled French rooster, I had to use a big hammer, and even so the thick lenses resisted its blows for a long time. A mindless, repulsive demon of destruction lived inside me. I don’t know where it came from or what happened to it later.

When I was a little bigger, but only a little bigger, I no longer dared grab instruments of murder and strike — simply, with childhood innocence — because, apparently, I had lost that innocence. Now I looked for various pretexts. For example, that something inside needed fixing, adjusting, examining. A lame story, since I didn’t know how to fix anything, nor did I even make an effort. And yet I felt I had a right to do what I did, and when my mother scolded me once for starting to hammer a nail into the dining-room cupboard in order to set up my toy train, I was resentful for a long time. Only Wicus, a trim little sawdust-filled boy doll with reddish blond hair, was exempt from the sphere of total destruction. I made him clothes and shoes, and he hung around in the apartment afterward, probably up to the war itself. Once, in the rush of an irresistible urge, I began to do him in, but immediately stopped and sewed up the hole in his stomach, or perhaps it was a hand pulled off; I don’t remember. I had long conversations with him, but we never talked about this.

Having no room of my own, I ranged over all the rooms, and slowly grew wilder. I stuck half-eaten candies under the table, where after years they made veritable geological formations of sugar. From my father’s suits pulled out of the closet I built mannequins on sofas and chairs, stuffing their sleeves with rolled paper and filling out the body with whatever lay at hand. When chestnuts were in season, I tried to do something with those beautiful things, which I loved so much I never had enough of them. Even as they spilled from my pockets, I would put more in my underpants. But I found out that chestnuts, deprived of their freedom and kept in a box, quickly lost their wonderful luster and turned dull, wrinkled, ugly. I tore open enough kaleidoscopes to have supplied a whole orphanage, and yet I knew that all they contained was a handful of bits of colored glass.

In the evenings I liked to stand on the balcony and watch the dark street come alive with light. The lamplighter, out of nowhere, silent, appeared, stopped for a moment at each street lamp, raising his rod, and instantly a timid glowworm grew into a blue flame. For a while I wanted to be a lamplighter.

Of the two powers, the two categories that take possession of us when we enter the world (from where?), space is by far the less mysterious. It, too, undergoes transformations, but their nature is simple: all space does is shrink with the passage of years. That is why the dimensions of our apartment slowly dwindled, as did the Jesuit Garden, and the stadium of the Karol Szajnocha II State Gymnasium, where I went for eight years. True, it was easy for me to overlook these changes, because at the same time I was growing more active and independent, venturing into Lvov more and more boldly. The coming together of places familiar to me was hidden by a series of adventures of ever-increasing range. That is why one becomes aware of the reduction only later.

“I thought that tomorrow was above the ceiling, as if on the next floor, and that at night, when everyone was sleeping, it came down.”

Space is, after all, solid, monolithic; it contains no traps or pitfalls. Time, on the other hand, is a hostile element, truly treacherous, I would even say against human nature. First, I had great difficulty, for years, with such concepts as “tomorrow” and “yesterday.” I confess — and I never told this to anyone before — that for a very long time I situated both of them in space. I thought that tomorrow was above the ceiling, as if on the next floor, and that at night, when everyone was sleeping, it came down. I knew of course that on the third floor there was not tomorrow but only a couple who had a grown daughter and a shiny gold box filled with greenish candy that stuck to your fingers. I didn’t really like that candy, which filled my mouth with the chill of eucalyptus, but I enjoyed receiving it, because it was kept in a rolltop desk that roared like a waterfall when it was opened. So I understood that by going upstairs I would not catch tomorrow red-handed, and that yesterday was not below us, because the landlord and his family lived there. Even so, I was somehow convinced that tomorrow was above us and yesterday below — a yesterday that did not dissolve into nonexistence but continued, abandoned, somewhere under my feet.

But these are introductory, and elementary, remarks. I remember the gate, stairs, doors, hallways, and rooms of the house on Brajerowska Street where I was born, and many people, such as the neighbors mentioned, but without faces, because those faces changed, and my memory, ignorant of the inevitability of such change, was helpless, as a photographic plate is helpless with a moving object. Yes, I can visualize my father, but I can see his figure and clothes more clearly than his features, because images from many years are superimposed and I do not know how I want to see him, the man turned completely gray or the still vigorous fifty-year-old. And it is the same with everyone I knew for a long enough time. When the photographs and portraits are lost, our complete defenselessness against time becomes apparent. You may learn of its action early in life, but that is theoretical knowledge and not useful. When I was five, I knew what old and young meant, because there was old butter and a young radish, and I knew a bit about the days of the week and even about years (the twenties were light in color and then grew dark toward 1929), and yet basically I believed in the immutability of the world. Of people especially. Adults had always been adults, and when they used diminutives with each other, I was slightly shocked — it was inappropriate; diminutives were for children. How absurd that one old man should say to another “Stasiek.” So time was for me then a motionless, paralyzed, passive expanse. A great deal took place in it, as in the sea, but time itself remained stationary. Every hour of school was an Atlantic Ocean one had to cross with manful determination; from bell to bell whole eternities passed, fraught with peril, and the summer vacation between June and September was an eon. I describe this unbelievable duration of hours and days as if I had only heard it from someone else and not experienced it myself, because I can now neither picture it nor conceive it. Later, imperceptibly, everything speeded up, and let no one tell me that impressions lie because all clocks measure the same rhythm of passing. My answer is, it is just the opposite: the clocks lie, because physical time has nothing in common with biological time. Physics aside, how does the time of electrons and cogs concern us? It always seemed to me there was some hidden trickery in the comparison, a vile deceit masked by the computational methods that equated all kinds of change. We come into this world trusting that things are as we see them, that what our senses witness is happening, but later it turns out, somehow, that children grow up and grownups start to die.

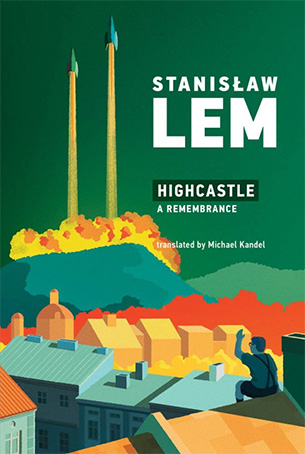

Stanisław Lem (1921–2006), a writer called “worthy of the Nobel Prize” by the New York Times, was an internationally renowned author of novels, short stories, literary criticism, and philosophical essays. His books have been translated into 44 languages and have sold more than 30 million copies. This article is excerpted from Lem’s memoir, “Highcastle: A Remembrance.”