Roxane Gay: Intentional, Home

When I earned a faculty position at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, I was thrilled. For the previous four years, I had lived in a very small town in eastern Illinois and for the five years before that I had lived in a very small town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. My entire adult life, my geographic circumstances had been dictated by professional urgencies.

In each place, I had an apartment that was mostly fine. I had small circles of wonderful friends. But I had never felt at home — the remoteness, the isolation, and being one of very few people of color made that all but impossible. Lafayette was going to be different, I told myself. With a population of more than 100,000, the town felt positively cosmopolitan. There would be, I hoped, a lot more to do, places to go, the ability to live more than an imitation of life.

Even with all that Lafayette promised, I was determined not to live there but in Indianapolis. It’s not that Indianapolis is paradise, but it is a lovely city. It has a reasonably diverse population. I found a gorgeous, brand-new apartment across from a fancy mall near the interstate. Getting to work would be easy, a straight shot down I-65, less than an hour commute. I was going to have access to shopping and interesting restaurants and interesting people. I would buy my first real adult furniture from a store other than IKEA. Maybe I’d fire up the dating apps and have some measure of a social life. If I was lucky, I would find community. Things were looking up.

I am originally from Omaha, Nebraska, so I am no stranger to living in small towns. But as I’ve gotten older, my tolerance for isolation has diminished. I have spent too many years living in the middle of nowhere. Anything is tolerable for a finite amount of time, but after spending most of my adulthood living and working in the middle of nowhere, I had reached my limit. I didn’t want to have to drive hours to the nearest airport. I didn’t want to have to drive hours or, worse, fly to a city where I can get my hair done. I no longer wanted to feel like an object of curiosity simply by virtue of my race. I was done with quietly seething while tolerating bewildering acts of racism. I was tired of feeling out of place. For too long, I had yearned for something different. I had yearned to feel less like a stranger in a strange land and more like someone who is, finally, home.

It was Central Indiana, a place where people flew the Confederate flag without irony even though Indiana was never a part of the Confederacy.

In the months before my first semester at Purdue started, as I got to know my new colleagues, mostly via email, they were deeply concerned about my living arrangements. The commute would be difficult, they said. And sometimes the Indiana winters were harsh. As a lifelong Midwesterner, I was not worried. An hour’s drive in the middle of nowhere is nothing at all, and after five years in the Upper Peninsula, where it snows more than 300 inches a year, I was confident I could handle any occasional snowfall that blanketed Central Indiana. In truth, I was salivating over the prospect of living in a place with more than 15,000 residents. Eventually, though, I buckled under the pressure, because I am nothing if not a people pleaser — always to my own detriment.

I ended up withdrawing from the lease on my beautiful new dream apartment and losing my deposit. Instead, I rented an apartment in Lafayette in a weird, creepy building with hallways that looked like they once hosted a series of horrifying unsolved murders. The apartments, though, were newly renovated, and it was a small town, so I had a three-bedroom, two-bath apartment with beautiful hardwood floors. My rent was a modest $1,400, and I consoled myself with the knowledge that a livable city was a mere hour away.

Living in Lafayette would be fine. It would be fine. Instead of driving an hour each way to work, I would have a breezy 10-minute commute across the river to West Lafayette. I would, as in the years prior, have large swaths of time to write. I would get to know my colleagues and maybe make some new friends. I would find my people and be more accessible to my students. I would be fine. It would be fine. It only took a few weeks to realize I had made a horrible mistake.

Lafayette was by no means the smallest town I’d ever lived in. It even had some of the creature comforts that make life a little easier without the liabilities of a big city — a multiplex, a Target, a few decent restaurants, a Starbucks with a drive-thru. But it was also Central Indiana, a place where people flew the Confederate flag without irony even though Indiana was never a part of the Confederacy. Because Indiana is an open-carry state, it was not out of the ordinary to see a man walking around in board shorts and a tank top, a gun holstered at his waist.

And then there were the men driving around in oversized pick-up trucks with “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and Ku Klux Klan imagery. Lafayette was inhospitable and lonely. When I left my apartment, I never felt safe. As a somewhat single Black lesbian, I found few local dating prospects. After a very brief foray on e-Harmony, I gave up on the idea that I might meet Ms. Right or even Ms. Right Now. My colleagues were nice enough, but I didn’t feel like I had or was part of a community. It was overwhelming, at almost 40, to feel like I had no future beyond work. I wondered, not for the first time, if I would ever find home, or if I would ever feel home.

One afternoon I watched a large pickup truck with a massive Confederate flag drive back and forth in front of my apartment building. I lay down in bed and stared at the ceiling and thought, I do not have to live like this. I do not want to live like this. I was grateful for my job. I love teaching and working with students, but I was weary of the unbearable compromise professors, particularly in the humanities, must often make — professional security and satisfaction at the expense of personal joy. A good job was enough until it wasn’t. Choosing to forgo living in Indianapolis was, ultimately, a valuable lesson in learning to trust my instincts and learning to allow myself the pleasure of doing what I want, even if it displeases others.

I am not an impulsive person. In general, I accept the way things are and have an annoying but useful ability to surrender to circumstances that feel unchangeable. There was a small glimmer of potential, though. My best friend lived in Los Angeles. One day, I was browsing flights and discovered that there were a few direct flights there every day from Indianapolis. The prices were fairly reasonable, so I bought a ticket, booked a hotel for a week, and flew west. I had no real plan, which was kind of thrilling. And then I did the same thing the next month, and the one after that. Before long, I was spending at least a week a month in LA.

Each time I stepped off the airplane into the grimy chaos of LAX, I felt more human. These sojourns were my first opportunity to spend a significant amount of time in a sprawling megalopolis. At first, I felt like a country mouse. Everything astonished me — the unfathomable and omnipresent traffic; the vibrant street art in bold, beautiful colors; the Mexican food and generally excellent restaurant scene; the museums; the weird little theater companies putting on weird little shows; the farmers markets with produce that didn’t seem real it was so beautiful. There was so much to do all the time. The weather was exceptional all the time. And, of course, there was the ocean — crystalline blue, stretching as far as the eye could see. That’s how I knew I had found a place where I belonged. I am not a beach person, but still I could appreciate the wonder of all that sand and water.

It was a relief to spend so much time in a very liberal place. More people shared my politics than not. There was a sense that the greater good matters. While there was a significant unhoused population, the city (mostly) didn’t try to hide it, and a lot of good people worked tirelessly to help the most vulnerable people in their communities. We are forced to confront inequality every time we leave the house and, frankly, that’s the way it should be until we figure out how to ensure that everyone has a safe, clean home they can afford, no matter what their financial situation is.

I now realize how much I sacrificed for so long, how I whittled myself into someone who could survive anywhere, making myself believe survival was enough.

It was truly life changing having the ability to be intentional about where I spent the majority of my time. After about a year of hotel stays, I rented an apartment downtown and bought a car. I found the local writing community, made new friends, and had a fun but fairly disastrous relationship with a very lovely woman. Three years later, I bought my first house, something I never imagined I would be able to do, especially in an expensive city like Los Angeles, where people with trust funds or mysterious sources of wealth regularly made all-cash offers over the asking price. I was terrified about making such an adult decision. At the time, I didn’t have a partner or kids or even a pet, all the things we tend to associate with home. It was just me, and as I signed 30 years of my life away, I tried to believe just me was enough.

The new house was perfect. I had space for all my books. I could paint the walls whatever color I wanted. I could hang things and not worry about losing a security deposit. In the backyard, there was a wizened old Japanese maple tree with a canopy of fecund branches covering the yard that I would, eventually, drape in sparkly Christmas lights simply because it made me happy.

Every day I see Black people just living their lives. I see all kinds of people, really. I feel more comfortable in my skin, and it’s beautiful to be in a place where difference is both unremarkable and celebrated. I now realize how much I sacrificed for so long, how I whittled myself into someone who could survive anywhere, making myself believe survival was enough. I know I will never again compromise on having a real home.

After I closed on the house and got the keys, I stood in the empty kitchen and looked around at all the bare walls. It was quiet and echoing because there was nothing in it to absorb the sound. I was going to have to fill all that space, which was somewhat daunting, but I also knew, down to the marrow in my bones, that even if I never brought a single thing into my new house, I was already home.

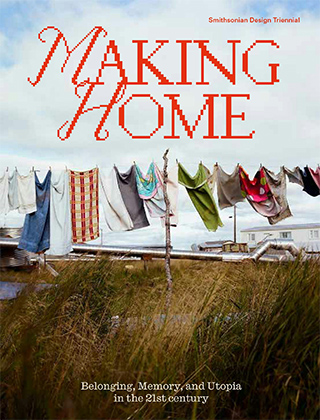

Roxane Gay is a writer, editor, and professor who splits her time between New York and Los Angeles. She is the author of several books including “Bad Feminist” and “Hunger.” This article is excerpted from the volume “Making Home: Belonging, Memory, and Utopia in the 21st Century,” edited by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León, and Michelle Joan Wilkinson.