How the Resistance of Materials Opens the Space of Reverie

Artists and designers expect to be confounded. They expect to be drawn into the unknown, especially at the uncertain early stages of a process. How different this is from those who work with methods to control an outcome. A material-based creative process begins with an action, and it is through such action that materials reveal their capacity to surprise us. These surprises come in many varieties.

For instance, an architecture student of mine tried to find an organizing principle generated from a specific controlled action and chance outcomes. She began with the action of clamping multiple sheets of window glass together and gradually tightening the clamp until the glass broke, which it did in a way that could not have been predicted. Creativity needs to proceed with some kind of resistance to or derailing of intent, presumptions, and preconceptions. In short, creativity must undo that which is known. After all, to be creative is to bring something new into being, not propagate what is already known.

Materials reveal problems and flaws, which are the very things production and craft work very hard to eliminate. For example, the first lenses were highly flawed, full of bubbles that interfered with optics. Subsequent production techniques aimed to eliminate these bubbles. While production techniques have been innovative and brilliant at finding ways to eliminate flaws, the creative process is just as likely to use flaws as agents of resistance or affordance, a kind of springboard to leap to other actions, to launch a conversation with and through material, leading to what previously could not have been imagined. The American furniture maker George Nakashima (1905–1990) is famous for working with boards other makers might consider “imperfect” because of their deep cracks. In fact, those cracks inspired his celebrated butterfly joints, which ultimately led to his signature tables that contrast the raw (and flawed) with the precision and control of those joints.

Materials reveal problems and flaws, which are the very things production and craft work very hard to eliminate.

Mastery of a medium or technique can lead to an instrumental relationship in which tools (or instruments or machines) dominate the exchange between author and work. In a conversational relationship, tools are more subordinated to the author, such as when a painter uses a paintbrush. How, then, can we master tacit knowledge and, with that knowledge, gain a degree of command while remaining open and free within the medium being worked? I think of the woodworker who has deep understanding, who can look at an oak board and know just how that tree grew and which side of the trunk was in the sunlight, and use that knowledge to select the board to make the table that will be straight and warp-free. All that knowhow is goal-oriented and masterful: the woodworker is working technologically — which etymologically can be understood as making logically. The logic of this kind of mastery is like that of good chess players, who have such a depth of knowledge that they understand the interdependence of actions and anticipate consequences far ahead.

The challenge for anyone working creatively is to use one’s mastery to raise new questions and “disregard the rules,” as the Renaissance artists demonstrated with perspective. For example, contemporary Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone has taken large individual timbers and, by carving away everything newer than a certain annular ring, “unearthed” the young tree within, branches included. He has had the sensitivity and freedom to allow the timber to guide him to original work.

In retrospect, it may look easy, but when facing a stubborn material or medium, one that resists our intentions, it is natural to feel a greater degree of difficulty and awkwardness and longing for mastery of the how. “If only I knew how to . . . !” The appeal of achieving a desired result has its place, but if creativity is the making of something from nothing or bringing the new into being, then a goal or result that does not exist cannot be known and thus cannot be aimed for. So how do we proceed? Questions, knowledge, observations, suppositions, and hunches all contribute to framing the situation, to grounding it, regardless of whether an artist is starting a painting or a designer is challenged to design a piece of furniture. The first encounter with any physical medium — pencil dragging on paper, a lump of clay squeezed, a chunk of wood hefted in the hand — starts us on a journey. Thoughts and feelings that come to mind are already entangled with the tacit, embodied knowledge we carry in our bodies, and in the material at hand. This is so natural that it is difficult to notice: We are prone to think our thoughts spring only from our minds.

We are prone to think our thoughts spring only from our minds.

The initial stirring to action, before anything has happened, seems to evoke what is commonly mischaracterized as our imagination. It’s a feeling, a burst of confident anticipation that finds its form in words: “I imagine . . .” or “I’m going to . . .” or the less insistent “I’m interested in . . .” What these declarations share is a strong sense of being unfettered. All is possible within one’s self, one’s “I”: “I imagine,” “I’m going to,” “I’m interested” are all voices of intention, a turning toward, facing the situation, paying attention, focusing energy.

What happens next is action. Hands move; tools are assembled and deployed; media and matter are rubbed, pressed, cut, molded, folded, strung, brushed. In short, all these things are acted on. At this point, training, experience, and skill will carry and propel the work only to a certain point. Knowhow has a trajectory and wants to follow it; however, any creative process demands openness to the unexpected, a responsiveness to the situation at hand, a recognition that what we “have in mind” may not be at all what is beginning to transpire before us.

Every process unfolds in its own unique way through bumps and failures. Forward motion and backtracking are familiar features and essential aspects of creativity. Why? Materials and media have resistance. They resist our efforts to force them to conform to intent. They wreck our plans. They can become the boulder blocking the road. Over the years, I’ve watched hundreds of students arrive at that moment of frustration and boredom, ready to give up. It is truly a remarkable moment: The emotional tenor seems so pessimistic, yet it is a necessary precondition for true insights. Resistance wakens the imagination.

All materials and physical media resist and react to action on them, each in its own profound way. Creativity is birthed in the crucible of resistance. When habitual ways are stymied, when we can no longer proceed, creativity becomes necessary. But first, before you think “what should I do?,” attention must shift to what is actually happening out there, to feeling it.

To empathize, to feel into, is the most intimate way of knowing another, including a material other. The American architect Louis Kahn (1901–1974) expressed this idea when he spoke of asking a brick what it wants to be: “What do you want, brick?” Asking such a question and listening to the answer requires action. The kind of action is less critical than the material’s response — how you strike a bell is less important than listening to the sound it makes. No medium, material, or technique is knowable until it is queried with action.

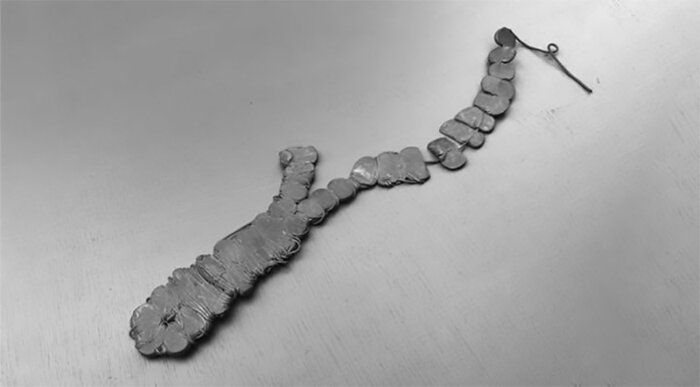

I realized this as a graduate student trying to make a work with two materials, lead and copper. I had tried for weeks to hammer the lead into sheets thin enough to be moved by ambient airflow when made into a mobile, using copper wire for the armature. The results were hopeless: The lead sheets could never be hammered thin enough to lose their clunkiness, and the mobiles I made were absolutely immobile. This dead-end turned out to be a new beginning when I came across a geological testing laboratory on campus with an incredibly powerful press. Winding copper wire around some lead bullets, I could sense the different attributes of the two materials that weren’t visually apparent. And then the press did a magical thing. Under the enormous pressure the copper wire and lead expressed their traits, the lead “flowing” bound by the “stretching” copper. Ordinarily hidden, their respective materiality appeared under the action of the press. From there, the work was propelled.

Material, as that experience illustrates, doesn’t give up insights easily. As much as forceful action reveals, it is initially and in most regards a pretty blunt act, hemmed in by preconceptions of how to act. Eventually, though, something gives — this is where mind and material begin to converse. More often than not, that initial conversation is easily derailed: A satisfying result tends to beget more of the same action that led to that result. This is where intent must exhaust itself and eventually let go.

The process of letting go is challenging. It lies beyond reason. It is guided by feeling, by emotional sensitivity and sensibility — our most vulnerable antennae.

The process of letting go is challenging. It lies beyond reason. It is guided by feeling, by emotional sensitivity and sensibility — our most vulnerable antennae. With time and practice, we may learn to understand eagerness, annoyance, intuition, and digging in our heels as critical guideposts along the creative path, as necessary preparations for arriving at a state of disinterest. As actions beget reactions and interactions, and as intent is confronted with the autonomous behavior of material, “trying too hard” and “want” are natural instincts to match stubbornness (of material) with more of our own stubbornness. New possibilities always drift into view when desire is exhausted — marked by a state of not wanting.

Eventually, the resistance of materials opens the space of reverie, that half-dreaming state in which the imagination can stir and where dispassionate contemplation penetrates far deeper than any overt effort.

Christopher Bardt is a professor of architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he has taught since 1988. He is a founding partner (with Kyna Leski) of 3six0 Architecture in Providence and the author of “Material and Mind,” from which this article is excerpted.