Peggy Guggenheim and the Self-Taught Artist You Probably Never Heard Of

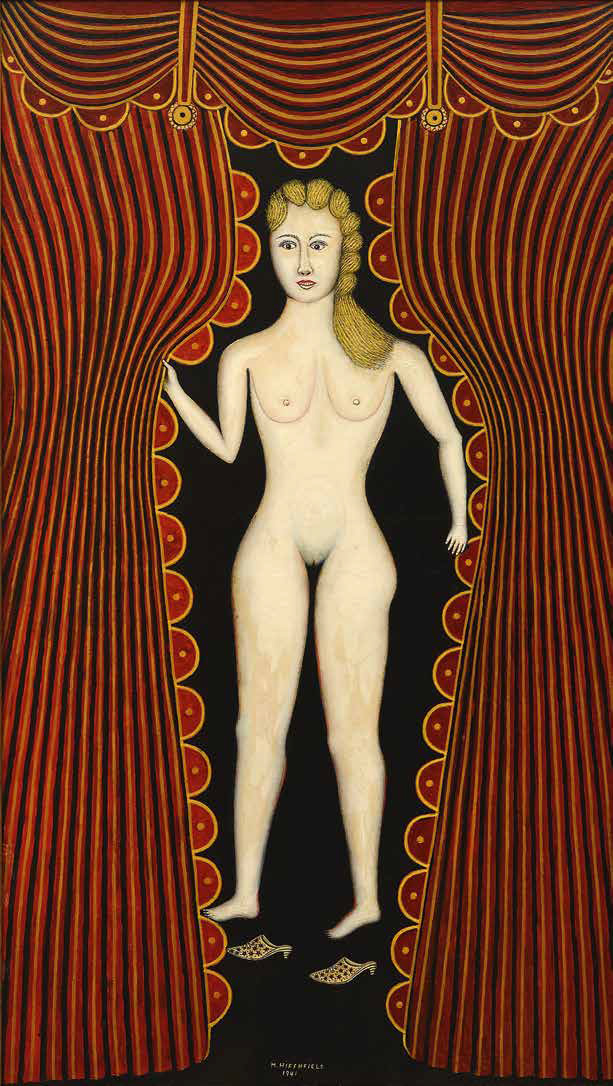

In 1942, the art collector, surrealist fellow-traveler, and bohemian socialite Peggy Guggenheim purchased “Nude at the Window” which she displayed in Hale House, her residence on East 51 Street off Beekman Place in Manhattan. The painting features a frontal nude framed by a theatrical expanse of red curtains striped in black and gold. In a characteristically fantastic repetition, the breasts and nipples of the figure are echoed by the red and gold half-circles edging the curtains. The contours of the nude’s sectioned hairstyle likewise recall the curving outlines of her breasts. A light dusting of pubic hair and a slight indentation suggest genitals. The nude glows against a dark ground, inhabiting a vase-like shape that also suggests, more vaguely, a vaginal form.

Hirshfield’s original title for the painting, “Nude at the Window (Hot Night in July),” suggests an explanation for the figure’s nakedness (relief from a sultry evening) while alluding to the elevated sexual charge — or heat — that energizes the picture. The nude makes no pretense to modesty. Far from covering her body, she opens the curtains to expose it. The heeled shoes near her feet only draw more attention to her nakedness. No other accessories or garments are visible. We are left with the slightly kinky juxtaposition of female nudity, bejeweled slippers, and velvet curtains.

According to an inventory of her collection drawn up for tax purposes in 1942, Guggenheim purchased “Nude at the Window” for $900. That same year, she acquired René Magritte’s “The Key of Dreams” for $75. Two years prior to that, she bought Mondrian’s “Composition” for $160. Given the lack of a significant base of Hirshfield collectors at the time, it is difficult to understand how a little-known self-taught artist commanded more than five times the price of a Mondrian and 12 times that of a now-canonical painting by Magritte.

Given the lack of a significant base of Hirshfield collectors at the time, it is difficult to understand how a little-known self-taught artist commanded more than 12 times that of a now-canonical painting by Magritte.

The sum Guggenheim paid for the painting speaks to the promotional skills and aesthetic intuitions that would make Janis, who opened his own gallery in 1948, one of the most successful art dealers in America. In the words of Alfred Barr, the founding director of MoMA, Janis was “the most brilliant new dealer, in terms of business acumen, to have appeared in New York since the war.”

“Nude at the Window” was the only work by a self-taught artist among the more than 250 paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, collages, and sculptures in Guggenheim’s possession in 1942. Her collection was based firmly in the European (and later, American) avant-garde, which makes her acquisition of Hirshfield’s painting — and the price paid for it — all the more noteworthy.

Though it does not explain the high cost of “Nude at the Window,” Guggenheim would have known that the painting had been celebrated in print within months of its completion in 1941. The celebrator was Breton in the pages of View, a New York-based art and literary journal that promoted surrealism to a largely American audience. In a front-page interview, the newly arrived refugee predicted that “A new spirit will be born from the present war. … As always in such periods when socially human life is almost worthless, I think we must learn to read with and look through the eyes of Eros — Eros who, in time to come, will have the task of reestablishing that equilibrium briefly broken for the benefit of death.” A perspective informed by love and desire would, according to Breton, help counter the nihilism and hopelessness of the war. Elaborating on this possibility, he turns to two American paintings:

Nothing seems to me to face this trial better than two pictures, both chosen as far apart as possible, and outside of surrealism: “New York Movie” by Edward Hopper, and Hirschfield’s [sic] Nude (at the window). The beautiful young woman, lost in a dream beyond the confounding things happening to others, the heavy mythical column, the three lights of “New York Movie,” seem charged with a symbolical significance which seeks away out of the curtained stairway. It is remarkable that it should also be between curtains, the one lifted, the other raised by itself, that Hirschfield’s nude appears in that unique light of a magician’s act which has been so well captured by this artist (the first great mediumistic painter).

“New York Movie” and “Nude at the Window” are, as Breton acknowledges, an unlikely pair. The bold colors and flamboyant patterning of Hirshfield’s painting conjure a space of carnivalesque display — a “magician’s act” — quite removed from the downbeat realism of Hopper’s distracted usherette in a darkened movie auditorium. Neither painting was made by a member of the surrealist movement and both are American rather than European. As such, they departed from Breton’s primary aesthetic focus.

The link drawn between the paintings is the presence of curtains: “It seems to me that in times of grave exterior crisis, this curtain, visible or not, expressing the necessity of passing from one epoch to another, ought to make itself felt in some way in every work capable of facing the perspective of tomorrow.” From Breton’s vantage, the motif of curtains touches upon both the present and the “perspective of tomorrow.” Where Hopper’s usherette is lost in a daydream that “seeks away out of the curtained stairway,” Hirshfield’s nude appears perfectly suited to the lavish curtains that surround her.

Breton ignores the feature that most obviously distinguishes Hirshfield’s female figure from Hopper’s — nudity. Nakedness would, of course, have been unthinkable for Hopper’s usherette at work. The different roles played by the red curtains in each painting follow from the manifest difference between the female bodies on display. The voluminous curtains in Hirshfield’s painting showcase the nude, while the modest drapes in “New York Movie” reveal only an empty gray staircase. The curtained stairway provides a path further into the movie theater, a path of no interest to the usherette, at least at this moment. The curtains in Hirshfield’s painting, by contrast, swirl around the naked figure as though excited by her presence. “Nude at the Window” cannot be separated from the sexual heat it generates. The painting all but demands to be seen “through the eyes of Eros.” Breton pairs two otherwise unrelated paintings — the one suggesting daydream as a momentary escape from workaday life, the other offering a realm of magical pleasure far beyond the quotidian. In juxtaposing the pictures, Breton suggests two paths beyond the deadening and dehumanizing effects of “the present war.”

Keeping Breton’s rapturous account of “Nude at the Window” in mind, listen to the heightened energy with which Janis describes the female figure in the same painting: “Like a dazzling apparition, this ivory pink creature with yellow blonde hair emerges from the mysterious black depths which we know are no more than the interior of a darkened room. The brilliant red drapes striped with black and yellow are gently held aside by one hand, and the other drape responds before it is touched as if she controlled it magically.” Janis’s reverie endows the female nude with qualities both spectral and magical. He evokes, but does not directly acknowledge, the erotic appeal that fuels these qualities. However unspoken at the time, that appeal may have been part of what inspired the purchase of “Nude at the Window” by Guggenheim, a vanguard art collector who was also a sexually audacious woman.

Guggenheim displayed the painting in her double-height living room beside several works by leading avant-garde artists. A sense of the difference Hirshfield’s work posed to the rest of her collection is suggested in a Newman portrait of Ernst seated in an elaborate armchair in the townhouse’s living room. At the left edge of the photograph, a sliver of Wassily Kandinsky’s “Landscape with Red Spots, No. 2” peeks into view. Above it hangs Duchamp’s “Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train,” below which, and largely occluded by the chair, is Picasso’s “Pipe, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc.” The oval painting higher on the wall, next to “Nude at the Window,” is Georges Braque’s “The Clarinet.” The four paintings date from the years 1911 to 1914 and offer a mini-survey of expressionism, dada, and cubism in those years. The only artwork contemporaneous with the Newman photograph is Hirshfield’s flamboyant nude of 1941. The other outliers in the picture — two kachina dolls from Ernst’s extensive collection of Native American artifacts — flank the armchair. The kachina dolls bespeak the surrealist turn to indigenous and tribal objects.

While the other paintings in the photograph appear securely fixed to the wall, “Nude at the Window” seems to have floated away from it and pivoted toward the camera. It is almost as though the painting were suspended in mid-air. “Nude at the Window” is nearly parallel to Ernst and in line with the camera. A closer look reveals that Hirshfield’s painting is hung on a wall adjacent to that shared by the other works.

Like Ernst himself, Hirshfield’s nude is at once embodied and entranced, present yet not quite fixed in place.

The play of light and shadow in the Newman photograph conjures a triangular wedge and a finger-like cylinder above and to the left of Ernst’s head. The wedge is, in fact, some upholstery exposed by a missing piece of the backrest. The apparent finger, which points at “Nude at the Window,” is more difficult to identity. It may be a diagonally oriented pillow, the left edge of which is illuminated by light, the rest obscured in shadow. The trailing cigarette smoke around Ernst’s head summons spectral creatures. “When he was shown the resulting print,” says one recent source, “Ernst was delighted to discover the image of a bird in the smoke clouds, as it chimed with his then current activity of drawing birds, and so seemed to demonstrate the serendipitous and subconscious aspects of surrealism.” “Nude at the Window” plays only a supporting role in Newman’s portrait of Ernst, but it is fully in keeping with the surrealist spirit of the photograph. Like Ernst himself, Hirshfield’s nude is at once embodied and entranced, present yet not quite fixed in place.

Whatever fueled Guggenheim’s interest in “Nude at the Window,” her admiration for it did not endure. In 1945, she sold the painting back to Janis and it remains in his family to this day. There is no record of how much money this transaction involved or precisely when it occurred. It is doubtful that Janis would have initiated it, as he already owned a number of Hirshfield’s paintings and could acquire new ones from the artist for considerably less money than he would have paid Guggenheim. The most intriguing question about this transaction, however, is why it occurred. What was it about “Nude at the Window” that so displeased Guggenheim that, within three years of its acquisition, she no longer wished to possess it?

The two answers that follow are speculative. They are based in pictorial interpretation rather than documentary evidence and in my perception of Guggenheim’s motives given her circumstances at the time. The first relates to a feature of “Nude at the Window” that is revealed when one sees the canvas close up and from an oblique angle. From that vantage point, it becomes clear that the figure’s nose protrudes into three dimensions. The painting’s appendage is not a detail that Guggenheim would have overlooked though it may have gradually become bothersome to her. She believed that the nose with which she was born irreparably marred her appearance. At the age of 22, she hired a cosmetic surgeon in the hopes of reducing its size and bulbousness. The operation was not a success, and Guggenheim felt that it left her worse than before. She had hoped for “a nose ‘tip-tilted like a flower,’” a line she remembered from Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King.” What she got was a nose “more potatoish than ever.” According to one biographer, Guggenheim subsequently “developed an aversion to the very subject. Her nose was something she did not talk about.”

A botched nose job is not a bad description of what the female figure in “Nude at the Window” seems to have undergone. The painting’s owner, as she saw it, suffered a similar affliction.

Hirshfield’s “Nude at the Window” gives “tip-tilted” a rather different association than Guggenheim intended. The tip of the nose is not so much tilted up as poking out and slightly to one side. A botched nose job is not a bad description of what the female figure in “Nude at the Window” seems to have undergone. In gaining material form and dimension, the nose has become an unlovely appendage. The painting’s owner, as she saw it, suffered a similar affliction.

The second reason Guggenheim may have grown to dislike “Nude at the Window” involves a gathering at which she was not present. In fall 1942, a series of photographs was taken in Guggenheim’s townhouse by another European exile, the fashion and portrait photographer Hermann Landshoff. The shoot featured Ernst, Guggenheim’s husband at the time, as well as Duchamp, Breton, and Carrington.

In one photograph, the four artists are joined by “Surrealism and Painting,” Ernst’s canvas featuring a large biomorphic creature with three bird heads and a limb. The creature is likely one of the incarnations of Loplop, Ernst’s avian alter ego. Duchamp and Carrington block the right side of the painting, depriving us of a view of Loplop at work on a geometric composition of black lines and red and yellow orbs against a field of green and blue. Ernst created Loplop’s abstract picture by drilling a hole in the bottom of a tin paint can which he slowly swung over the canvas. The artist dubbed the technique “oscillation.” In a characteristic paradox, Loplop’s seemingly precise, hand-painted abstraction is in fact the result of drippings from a can. The creature’s careful attention to the task of painting — its delicately placed hand and finely bristled brush — is belied by Ernst’s embrace of chance effects.

At the moment the photograph was taken, “Surrealism and Painting” was en route to First Papers of Surrealism where, as Newsweek recorded, it would be ensnared within Duchamp’s web of twine. Breton and Duchamp may well have been at Guggenheim’s home that day to move (or supervise the transport of) the painting a mile west to the Whitelaw Reid Mansion.

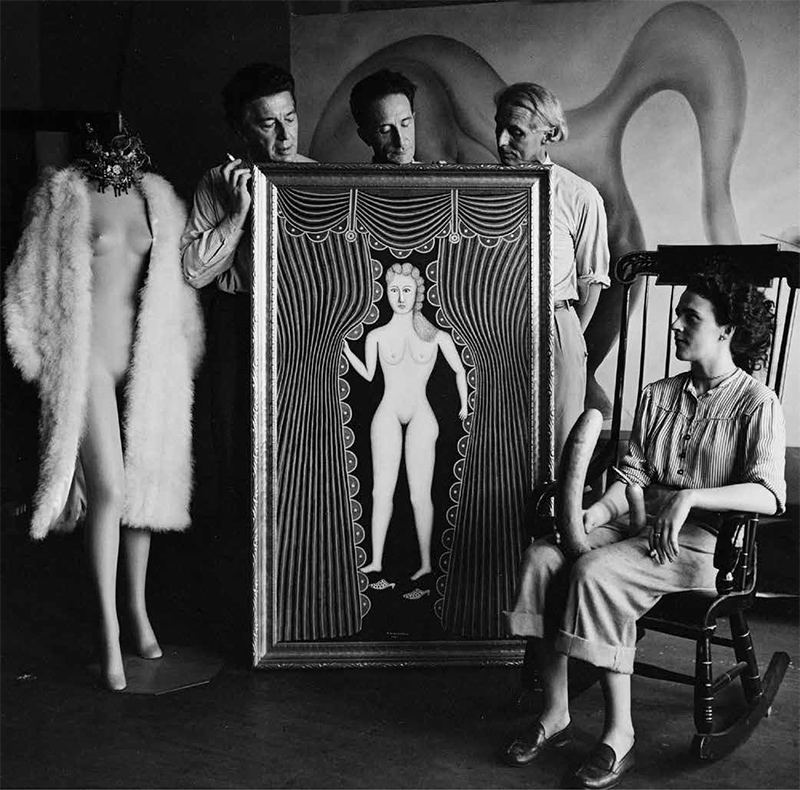

In another photograph from the same shoot, a second painting from Guggenheim’s collection is added to the scene. Ernst, Duchamp, and Breton stand behind “Nude at the Window” and look down at it as though transfixed. To one side of Hirshfield’s painting, Carrington sits in a rocking chair with a large, phallic-shaped gourd between her legs. At the other side stands a headless female mannequin, naked save for a mask and what may be one of Guggenheim’s signature fur coats. The mask, on close examination, appears to be a tangled assembly of studded fabric, rhinestones, velvet, beads, a bracelet, and some tiny twigs and leaves. Although this heterogenous object has been placed at eye level, there is no face for it to cover. The mannequin is headless. In an appropriately absurdist gesture, a mask that is not a mask covers the place where a face should be.

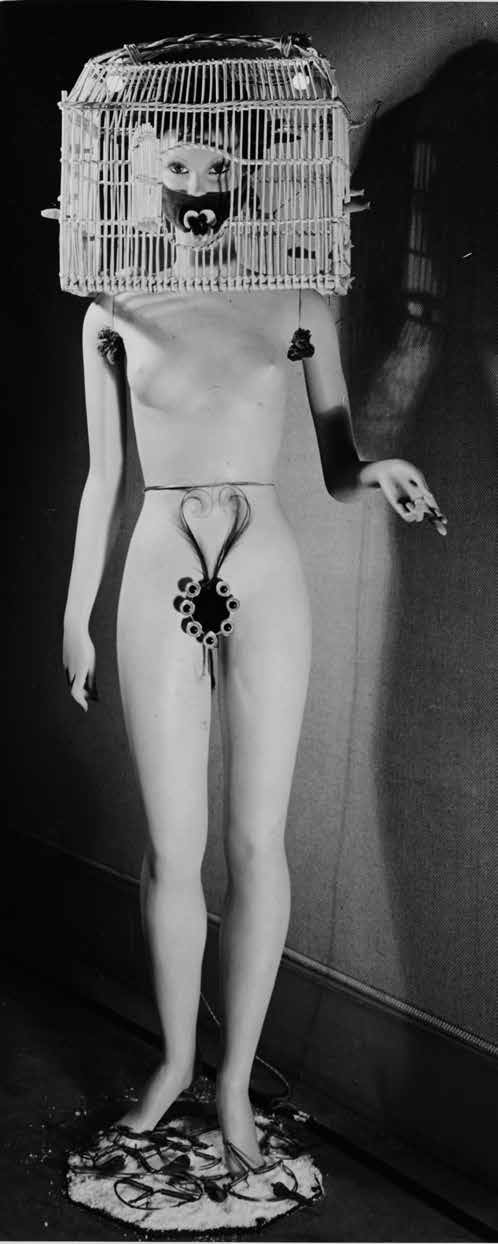

The mannequin in Guggenheim’s townhouse echoes the broader surrealist attraction to such objects. Often costumed with cages, feather, fur, or fetish gear, surrealist mannequins became staging grounds for sexualized subjugation and male fantasy. The most famous expression of this fascination was the hall of mannequins representing “the most beautiful streets of Paris” at the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition. Masson’s contribution, displayed under the street sign “Rue Vivienne,” was a mannequin with its head encased in a bird cage, pansies tucked into its underarms, a peacock-feather G-string, and a tangle of cords at its feet. A small door at the front of the cage has been left open. Far from providing a sense of release, the open door offers a view of the gagged face of the mannequin. The silencing of the female figure is perversely ornamented by a fabric blossom that emerges from the gag.

Breton, Ernst, and Duchamp were extensively involved in the International Surrealist Exhibition that presented the mannequin as a site of both desire and disorientation. In Landshoff’s photograph, the three men stand side by side in the center of the visual field, their bodies largely hidden by the painting on which they focus. The men are presented as viewers of “Nude at the Window” rather than as objects on visual offer in their own right. Three female figures — one molded, one painted, one living — enact various forms of eroticized display. The tableau staged for Landshoff’s camera places Hirshfield’s nude on a continuum with a fetish-strewn mannequin and a sentient woman with a phallic surrogate. Surrealist players and props are drawn into the forcefield of the painting even as the peculiar eroticism of the painting is amplified by its newfound companions.

By the time Guggenheim acquired “Nude at the Window,” her marriage to Ernst was deeply troubled, not least because she believed he was still in love with Carrington, his prior paramour. For this reason among others, her marriage to Ernst descended into rancor and recrimination. The couple divorced not long after this photo shoot. In light of these tensions, the photograph with her husband, his friends, and “Nude at the Window” might be understood as an elaborate joke at Guggenheim’s expense. In her home (and her absence), she is reduced to a headless mannequin to be posed and played with, a bejeweled and naked dummy draped in one of her own furs. Although there is no record that Guggenheim saw any of Landshoff’s photographs, it seems safe to assume that she would not have been amused by the theatrics they record.

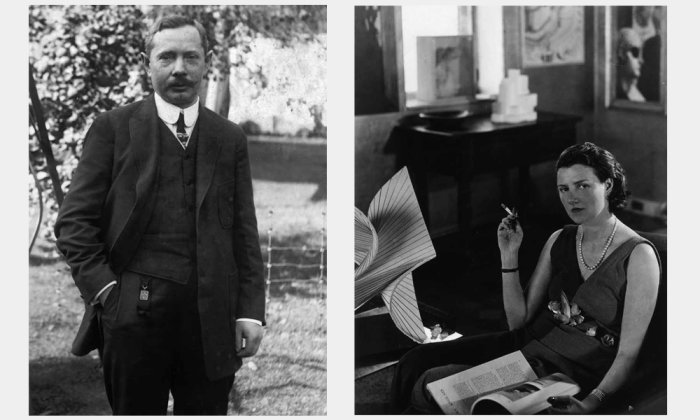

Richard Meyer is Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor in Art History at Stanford University. He is the author of several books, including “What Was Contemporary Art?” and “Master of Two Left Feet,” from which this article is excerpted.