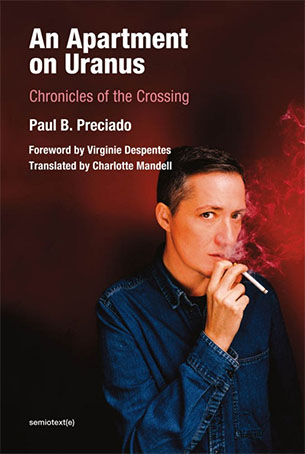

Paul B. Preciado: The Bullet

Homosexuality is a silent sniper who plants a bullet in children’s hearts in school playgrounds, he aims without caring if they’re the kids of yuppies, agnostics or diehard Catholics. Its hand doesn’t tremble, neither in the schools of the sixth arrondissement nor in working-class neighborhoods. It shoots with the same precision in the streets of Chicago, the villages of Italy, or the suburbs of Johannesburg. Homosexuality is a sniper blind as love, bursting forth like laughter, as gentle as a pet. And if it tires of using children as targets, it shoots a volley of stray bullets that will lodge themselves in the hearts of a farmer, a taxi driver, a rapper, a postwoman on her rounds… the last bullet reached an 80-year-old woman during her sleep.

Transsexuality is a silent sniper who plants a bullet in the chests of children standing in front of a mirror or counting their steps on their way to school. It doesn’t care if they were born from artificial insemination or Catholic coitus. It doesn’t ask itself if they come from single-parent families or if Dad wore blue and Mum dressed in pink. It trembles neither from the cold of Sochi nor from the heat of Cartagena. It opens fire on both Israel and Palestine alike. Transsexuality is a sniper blind as laughter, bursting forth like love, as gentle and tolerant as pets are. From time to time, it aims at a teacher in the provinces or at a family man, and then, boom.

For those who have the courage to look straight at the wound, the bullet becomes the key to a world they had seen nothing of before. The curtains part, the “matrix” breaks apart. But among those who carry the bullet in their chests, some decide to live as if they felt nothing.

Others compensate for the weight of the bullet by acting like Don Juan or like a princess. Doctors and the churches promise to extract the bullet. They say that in Ecuador, a new Evangelical clinic opens every day, to re-educate homosexuals and transsexuals. The lightning-strikes of faith become electric shocks. But no one has ever figured out how to get the bullet out. Neither Mormons nor Castrists. You can bury it more deeply in the chest, but you can never remove it. Your bullet is your guardian angel: it will always be by your side.

I was three years old when I felt the weight of the bullet for the first time. I knew I was carrying it when I heard my father call two foreign girls walking hand-in-hand in the street “disgusting, dirty dykes.” My chest started to burn. That night, without knowing why, I fantasized for the first time that I was escaping my city and that I was leaving for another country. The days that followed were days of fear, and shame.

It is not hard to imagine that among the adults who are taking part in the current angry demonstrations that some of them bear, embedded in their plexus, a red-hot bullet. By simple statistical deduction, and knowing the virtuosity of snipers, I know that some of the demonstrators’ children already carry the bullet in their heart. I don’t know how many they are, or how old they are, but I know that some of them have chests that burn.

That night, without knowing why, I fantasized for the first time that I was escaping my city and that I was leaving for another country.

They are carrying banners that have been placed in their hands, which say “Hands Off Our Stereotypes.” But they know that they’ll never be equal to these stereotypes. Their parents shout that LGBT groups should never venture into schools, but these children know that they’re the ones who bear the LGBT bullet. At night, as when I was a child, they go to bed with the shame of being the only ones to know that they are a disappointment to their parents, they go to sleep with the fear that their parents will abandon them if they find out, or would prefer it if they died. And perhaps they dream, as I did before them, that they are running away to a strange land, in which children who bear the bullet are welcome. And I want to say to these children: life is wonderful, we are waiting for you, there are many of us here, we have all been hit by the bullet, we are lovers with chests wide open. You are not alone.

— Paris, 15 February 2014