Our Obsession with Hypocrisy Is Making Things Worse

You hypocrite.

These words hit people hard. They sting. Your pulse may quicken upon seeing them.

This aversion has deep roots. For many people, disgust of hypocrisy is part of the cultural fabric that weaves together their beliefs, judgments, and decisions. Religion provides an obvious starting point. In the Bible, Jesus rails repeatedly against the hypocritical Pharisees. Dante’s “Inferno” shows vividly what their fate could be: Hypocrites are banished to the second-lowest circle of Hell, together with “everything that fits / The definition of sheer filth.” There, they are forced to trudge around wearing cloaks that have dazzling gold on the outside, but which are lined with crushing lead within, making them as deceptive as their wearers.

Philosophers have also given hypocrisy a hard time, from Plato onwards. His “Republic” defines the “perfectly unjust man” as someone who has “secured for himself the greatest reputation for justice… while committing the greatest wrongs.” The 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau hated hypocrisy with an unnerving intensity, writing:

“The vile and groveling soul of the hypocrite is like a corpse, without fire, or warmth, or vitality left. I appeal to experience. Great villains have been known to return into themselves, end their life wholesomely, and die saved. But no one has ever known a hypocrite becoming a good man.”

Surprisingly, modern philosophers are not much more restrained. Hannah Arendt admits that “only crime and the criminal, it is true, confront us with the perplexity of radical evil; but only the hypocrite is really rotten to the core.” Judith Shklar thinks that we see hypocrisy as “the only unforgivable sin” remaining today.

Yet it is Sigmund Freud who offers perhaps the most haunting evaluation of hypocrisy — and why it’s so deeply woven into the fabric of society. In his not-so-cheery 1915 title “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death,” which came out in response to the horrors of World War I, he wonders how such a sea of slaughter could explode so quickly, and how these impulses were contained in peacetime.

Freud theorizes that human nature consists of “instinctual impulses” that fulfill certain needs. These may be cruel and violent ones that involve us taking what we want, when we want it. But these impulses are neither good nor bad in themselves — we just end up labeling them as so, based on the needs and demands of society. What civilization does is suppress these instincts by instilling principles. In Freud’s view, we want to kill someone who humiliates us, but religious teaching (or the fear of punishment) holds us back. Society, he believes, keeps tightening moral standards and taking us away from our primal impulses. But we can’t suppress them entirely; they are ready to “break through to satisfaction at any suitable opportunity.”

Society makes acting against our “true” impulses the price of harmony and (relative) safety. This is the hypocrisy at the core of civilization. Here’s how Freud puts it all together:

“Anyone thus compelled to act continually in accordance with precepts which are not the expression of his instinctual inclinations, is living, psychologically speaking, beyond his means, and may objectively be described as a hypocrite, whether he is clearly aware of the incongruity or not. It is undeniable that our contemporary civilization favors the production of this form of hypocrisy to an extraordinary extent. One might venture to say that it is built up on such hypocrisy…”

For Freud, war shows what happens if some of the checks on our instincts are removed. In this view, hypocrisy is not just a necessary byproduct of civilization; it’s what makes civilization possible in the first place.

Today, rather than believing — like Freud — that society depends on hypocrisy, most people probably think that society is profoundly harmed by it. Indeed, our hatred of hypocrisy seems almost compulsive. We are conditioned to see it everywhere; our judgments form quickly and intuitively.

The problem, however, is that we often take our accusations of hypocrisy too far; the cure becomes poisonous at too large a dose.

The uncomfortable truth, which we know at some level, is that societies work better if we can tolerate some forms of hypocrisy. Sometimes our hypocrisies are just an expression of our humanity, of flawed yet decent attempts to navigate a complex world. Sometimes they’re the only way of coping with inescapable conflicts that would otherwise tear us apart. And often they allow compromises that get us to a better place overall, even though we’d prefer not to admit it.

Instead, our drive to seek and destroy all hypocrisy has created a trap — and it’s closing around us rapidly. There are two main ways that the trap works.

First, our drive to kill hypocrisy breeds more hypocrisy.

When calling out hypocrisy, at least part of our desire is to feel good about ourselves. The accusations make us feel superior, and that’s satisfying. But often we tell ourselves — and others — that we are motivated purely by principles, by a quest to crush injustice.

In other words, a gap emerges between our pristine self-image and our mixed motives. We feel better about ourselves than we deserve to. We fall into a self-satisfied certainty that pushes for rigid, inhuman standards of consistency for others that we don’t — and can’t — live up to ourselves. Our criticism of hypocrisy ends up bending back into hypocrisy itself.

The problem, however, is that we often take our accusations of hypocrisy too far; the cure becomes poisonous at too large a dose.

You can see traces of this risk even in clear-cut cases like Partygate. The people who gathered outside the house of Boris Johnson’s leading adviser to shout “Hypocrite!” were not following social distancing rules themselves. The leader of the opposition, Johnson’s main accuser, found his own beer-drinking under scrutiny. While eight in 10 people said that they were following COVID regulations “all” or “nearly all” of the time, only one in 10 thought that others were. It seems likely that they were lenient when judging their own actions but harsh when judging others.

The other danger is that we exhaust the concept of hypocrisy by overusing accusations, so they start to lose their power.

When people see the label hypocrisy applied to the slightest inconsistencies, they start to think that it’s just another term of abuse. Accusations are no longer about uncovering truth and maintaining trust — they’ve become endless and therefore meaningless. And if we empty hypocrisy of meaning, we empty our principles of meaning as well. That takes us closer to a bleak and cynical world where no one cares about being called a hypocrite because they can get what they want regardless.

This is the hypocrisy trap. Taking accusations too far can actually create more hypocrisy — or exhaust the force of accusations altogether. Our desire to crush hypocrisy completely can only backfire.

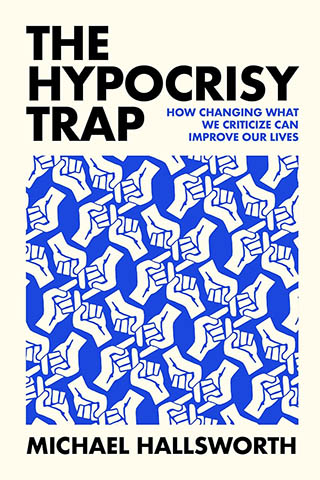

I’m not excusing or encouraging hypocrisy in general. Being consistent with our principles matters, and my book “The Hypocrisy Trap” offers new ways of achieving that goal. But to avoid the trap, we also need to be more selective about what kinds of hypocrisy we go after. We need a guide for which kinds we target and which we tolerate (as hard as that can be). That way, we can suck the poisonous parts of hypocrisy out of our societies without making accusations toxic through overuse.

In the book, I offer three main ways to address hypocrisy healthily in our politics, businesses, and relationships. Some of these ways will feel counterintuitive, and some will be controversial.

The first path is to adopt new ways to increase our own consistency. They are practical fixes, such as redesigning our workplaces or changing how we make commitments. We can make ourselves more likely to stick to our claims and principles, thereby reducing our hypocrisy.

The second path is to reduce the risk of accusations. Maybe the first route fails, and we can’t find a way to be more consistent. In that case, we can still use our new insights to anticipate and avoid what will make people angry. Politicians can show how they are making reasonable compromises; companies can spark minimal irritation when discussing their good deeds. If accusations are out of control, we need at least some defensive options.

The third path is to change our views about hypocrisy. We need a guide for when to call out hypocrisy and when to tolerate it. We need to ease off on accusing people or companies who are genuinely aiming for something better but are failing to achieve their goals. And why we need to let some harmless strutting go by, even if it makes us feel sick.

But once you recognize that complete consistency is unrealistic, what matters is the reaction.

To be sure, some kinds of hypocrisy are poisonous. We can spot and target the ones that are heavy with injustice that causes us harm. For instance, there is the particular danger of “double-standards hypocrisy,” where we judge ourselves or members of groups we are in differently from others while still paying lip service to the idea that everyone should be treated the same. Like the way politicians who thought COVID-19 restrictions were for other people, not them.

Double standards can become patterns of thought that self-reinforce and intensify. As they spread throughout society, they begin to close off paths to tolerance and reconciliation. It is a short journey from denying common ground with another group to denying their humanity altogether.

Many of the societies I have in mind are Western democracies. They prize the ideal of the consistent, self-contained individual, placed on an equal footing with others under the rule of law, which means they are particularly bothered by hypocrisy. Other cultures are more accepting of the need to vary one’s views across social contexts. Maybe we shouldn’t expect so much consistency from ourselves; maybe rethinking hypocrisy can also help us reassess our ideas of the self.

But once you recognize that complete consistency is unrealistic, what matters is the reaction. How do we reject cynicism, hold onto ideals, and continue striving to narrow the gap between aspirations and reality? How do we avoid self-righteously setting others up for failure? And how can we do this while also nailing the hypocrisy that harms us all?

Michael Hallsworth is a leading figure in applying behavioral science to real-world challenges. For the last 20 years, he has been an official and an adviser for governments around the world. He built a 250-person consultancy business and has held positions at Princeton University, Columbia University, Imperial College London, and the University of Pennsylvania. Michael has published several books, including “The Hypocrisy Trap,” from which the article is adapted.