On English Melancholy

Melancholy has an old history. Already around in antiquity, and present in civilizations that each in their own way have thought of themselves as modern, it was long conceived as an illness that afflicted creative types — Aristotle pondered why it was always the thoughtful ones, like poets, artists, and philosophers (himself included), who succumbed. It was associated, too, with the dour presence of Saturn, the sixth ringed planet from the sun, named after the ancient devourer of children. Many will know Dürer’s personification of melancholia. In the woodcut of 1514, she is the one with her head propped up in her hand, picking disinterestedly at her geometry problem while her immediate field of vision is littered with a myriad of interesting subjects waiting to be analyzed. (Is there a certain recognizable angle at which Melencolia cocks her wrist and props her head?) She looks across this landscape but doesn’t really take it in, staring off into the distance, only half invested in what her right hand is doing.

Albrecht Dürer, “Melancolia I,” 1514 / Public Domain

I am told that this saturnine image initiates a strain of melancholy tied to a peculiarly German notion of modernity, culminating in Max Weber’s idea of the “iron cage,” where we are captive to the rules of rationality. For the French, it’s ennui. Closer to boredom, it’s endless, it’s annoying, but at least you kind of look good when you have it.

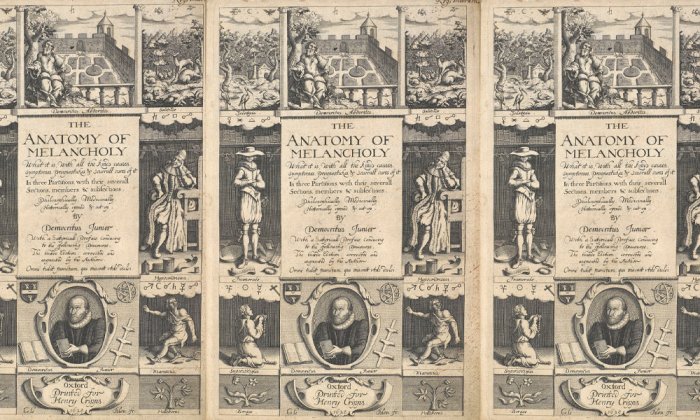

In England, melancholy arrived with the early glimmerings of empire and capitalism. First published in 1621 as a weighty 900-page quarto volume, “The Anatomy of Melancholy” by Robert Burton — clergyman and librarian for life of Christ Church College, Oxford — would balloon further, filling with more and more digressions, dissections, and descriptions of melancholy in five new editions right up to the author’s death in 1640. The 1628 third edition gained a frontispiece engraved by Christian Le Blon, a composite of 10 scenes representing different aspects of melancholy. The image center top depicts Democritus, the ancient Greek materialist philosopher, and below him, and the title in an oval frame, is his epigone, the ruff-collared Democritus Junior (Burton’s pseudonym). The Greek philosopher is pictured sitting under a tree, studying the anatomy of the animals around him for the “seat of black choler,” while “Over his head appears the sky, / And Saturn, Lord of melancholy.” To the right of the title is the Hypochondriac, who adopts the same pose as Dürer’s saturnine figure.

The other figures suffer from melancholy too — afflicted by solitude or jealousy, or victims of love, superstition, madness — but the vignettes in the corners show the cure, in the form of two herbs, borage and hellebore. As many commentators have noted, Burton appears to be possessed of an uncommonly good sense of humor for a self-proclaimed melancholic. (But everyone knows that stand-up comedians can be seriously depressed. Even the image of the sad clown has a long history, stretching at least as far back as the 19th century.) Melancholy was said to be induced by ponderous thinking, and “commerce with others” was proffered as one cure for solitude.

Written decades before the Acts of Union in 1707 sutured England to Scotland and Wales (but not yet Ireland), and before the idea of a unified British Isles had fully ripened, Burton’s voluminous text intimates the full scale of the problems that confronted a man with too much time on his hands. While Burton encouraged work and industry as the means to escape idleness, his continual revisions to the text make it clear that he felt the case on melancholy was far from closed. More pages had to be added. The purported cure of “working through” melancholy (a supplement to the herbal remedy offered in Burton’s frontispiece) could be read in another way, as a glimpse of the encroachment of the world of commerce. While the rise of capital belonged to the Dutch in the 17th century, it would move west to London, which became, according to Giovanni Arrighi’s formulation, the site of the third “systemic cycle of accumulation” in the 18th century.

Burton himself wished the English were more like the Dutch. He claimed his countrymen were a melancholy lot, living “like so many tortoises in our shells, safely defended by an angry sea, as a wall on all sides.” The English as the tortoise people, a people in a half-shell (testudines testa sua inclusi). Totally soft and unprotected on the inside, and hard as a nut on the outside, but most of all wrapped up and protected by its angry sea-wall. The other problem, Burton averred, was that the English were prone to idleness, when everyone knew that industry was the key to a nation’s wealth. If they wanted to be on top of the world, they had to look to the Low Countries, where “Industry is a lodestone to draw all good things; that alone makes countries flourish, cities populous, and will enforce by reason of much manure, which necessarily follows, a barren soil to be fertile and good.”

It’s strange. Once I read that, I could not unread it. I started to find tortoises everywhere, including in a haunting painting attributed to Thomas Black that I chanced upon in Philadelphia. According to the label, the 18th-century still life celebrates an English gentleman’s collection of natural wonders. It’s supposed to reflect a fascination with exotic specimens such as the tortoise, whose nine unfertilized eggs can be seen behind her. But I don’t see fascination: I see pillaging and plunder. Set into a barren mountainside, the tortoise is surrounded by natural wonders that have been artificially extracted from the sea and put on dry land. Surf and turf. This picture is all about shells. Seashells are strewn around, the tortoise has a shell, and the eggs have shells. The eggs are harvested, but never hatch. Isn’t this a melancholy allegory of British capitalism?

Melancholy was closely associated with the theory of sentiment that became a key feature of 18th-century philosophical thought and the abolitionist movement. More recently, it has figured in the work of Ian Baucom and Anne Cheng, who in different but connected ways use the term to tackle the subject of racial capitalism as our common inheritance. The word’s appearance in the title of “Melancholy Wedgwood” strategically and subtly gestures towards this rich academic literature on the term and its political implications, at the same time as it proposes to think of melancholy on more intimate terms: as the very way in which we apprehend Josiah Wedgwood’s ceramics, the way we touch the bodies he made, including that of his own historically conditioned self.

I think this word also provides a contrast to the language of nostalgia to which Wedgwood has colloquially been bound. The widespread cultural currency of nostalgia, once understood as a fatal homesickness, has recently been studied as “an emotional disposition at once historically determinate and one that outlived its own conditions of possibility.” Though melancholia was, like nostalgia, examined as a medical condition, it was also, according to Freudian psychoanalysis, more elusive. Unlike nostalgia, there was no lost home to return to, to stop the sickness. Nor did it follow a clear timeline or chronological progression. Unlike mourning, often personified as a weeping woman, there was no clear beginning, middle, or end, when you could stop weeping for the dead king or your departed kindred once you realized they would never return. And yet, as Cheng has argued, this unhomely quality gives melancholia its political power, as a profoundly disruptive sense of loss that has the capacity to reshape you from both the inside and the outside.

Iris Moon is Associate Curator in the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is coeditor with Richard Taws of “Time, Media, and Visuality in Post-Revolutionary France” (Bloomsbury) and author of “Luxury after the Terror” (Penn State University Press) and “Melancholy Wedgwood,” from which this article is excerpted.