More Notes on Repetition and Our Brains

Last month, we published a widely read story on repetition in painting and photography. Here, the author returns to the theme, extending it into poetry, photography, music, and even the evolutionary roots of why repetition brings us pleasure.

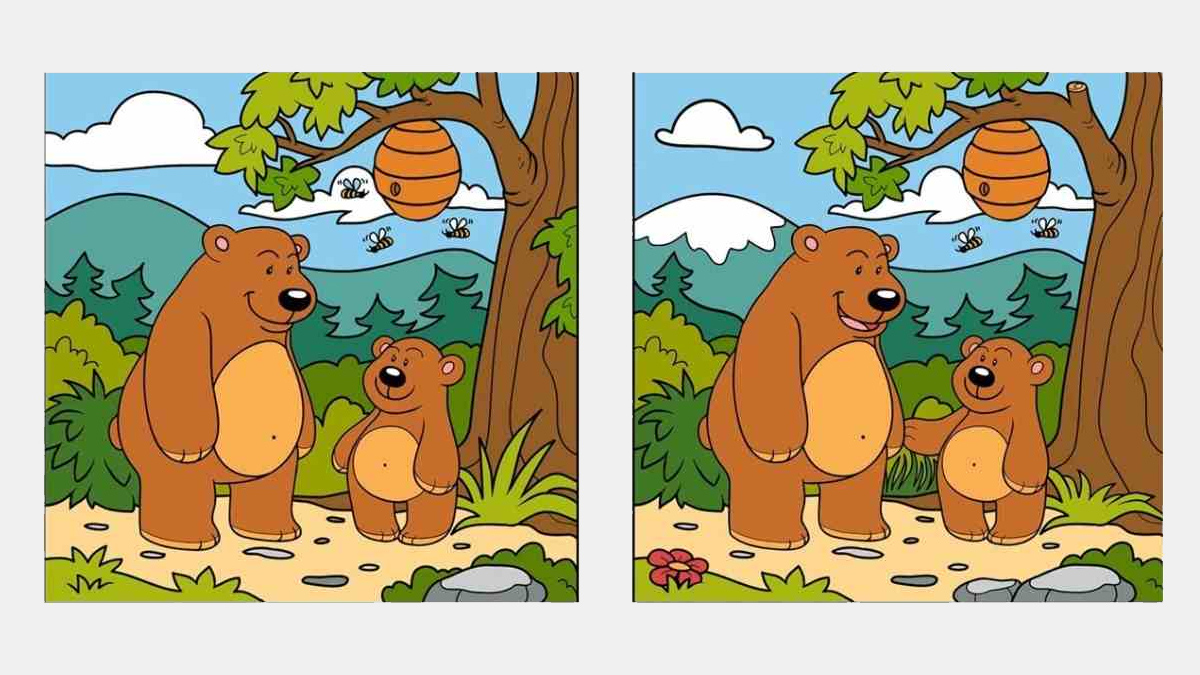

There is a popular game online called Spot the Difference. The idea is to find the differences between two similar images. For example:

The game raises an interesting question: Are the two images repetitions of one another? Well, it depends. If you mean perfectly identical, the answer is no — the game is to find the differences, in this case 12 of them. That’s what makes it fun: discovering the small differences elicits pleasure. But if you mean very much alike, so much so that they could reasonably qualify as repetitions, then the answer is yes. They are, as jazz musicians tuning their instruments often say, “close enough.”

Here is what the noted philosopher and psychologist William James said about “close enough” over a century ago in his book “The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1”:

The perception of likeness is practically very much bound up with that of difference. That is to say, the only differences we note as differences, and estimate quantitatively, and arrange along a scale, are those comparatively limited differences which we find between members of a common genus.…To be found different, things must as a rule have some commensurability, some aspect in common, which suggests the possibility of their being treated in the same way.

When James speaks of “comparatively limited differences,” he is talking about the kind of thing that allows repetitive observations like “This salad is exactly like that one except it has anchovies instead of almonds” or “This house is the same as that one except the door is red, not black.” The evidence shows that human beings are, in fact, hardwired to detect both kinds of repetition: identical (same) and identical but with a “comparatively limited difference” (same/except). It is also true, as evidenced by Spot the Difference, that exercising this ability is pleasurable.

And this is a key to understanding why same/except judgments are ubiquitous in the arts. They invite the audience to make those judgments because doing so introduces pleasure when experiencing the art form.

Here’s an example. English poetry’s use of rhyme goes all the way back to the 10th century and the Old English Rhyming Poem. By rhyme I mean the so-called end-rhyme that you find in couplets like this:

I am searching for a rhyme

To spice this couplet. Let’s say, thyme.

Everyone knows that rhyme and thyme rhyme while rhyme and foot don’t. But what do they know that enables them to make these judgments? They know that rhyme/thyme is a same/except kind of repetition. Here is a highly simplified explanation limited to monosyllables to make the point.

Consider words like rhyme and time as having a front part and a back part:

The boundary is just before the stressed vowel [á]. Deciding that two monosyllables rhyme goes like this:

1) Divide each word into front and back parts.

2) Are the back parts the same?

3) Are the front parts different?

If the answer to (2) and (3) is yes, then the words rhyme.

Except: r / t

Same: -áym / -áym

The test shows that rhyme doesn’t rhyme with foot and not even with rime (as in “hoarfrost”). Since running the same/except test on putative rhyming pairs is fun — a version of Spot the Difference — you might say that when John Milton decided to eschew rhyme in his poetic masterpiece, “Paradise Lost,” he took a lot of the fun out of it. Not all of the fun. He did retain metricality, another form of Spot the Difference.

The same/except distinction is not limited to poetic rhyming. Roni Horn has produced a book that pairs photographs of the same but not quite identical face. Here, too, the pleasure is in detecting the difference.

As a commentator on the web put it, “Horn requires that you look and discover. The ‘identity’ is always different.“

Horn’s photography is an exercise in visual rhyme. We don’t need to go very far to find it in painting as well. Consider Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans.” It consists of 32 identically painted cans of soup displayed in four rows of eight cans each. Here is the first row:

It is a perfect example of same/except repetition. Each can is the same as every other can except for the label. The kind of soup differs. And it goes on for three more rows, each can rhyming with its neighbor: a visual version of end-rhyme.

What about music? Identical repetition occurs all the time. Practically any jazz standard repeats the first eight bars and, after the intervention of a so-called bridge, repeats them again. You find the same thing in Mozart’s “Rondo alla Turca” from his “Piano Sonata No. 11” to name just one famous example.

Same/except repetition is equally common in music. The first two bars of Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll” are rhythmically the same as the third and forth bars. But they are different in pitch: The latter is one step higher. This difference permeates the entire tune. This is music’s counterpart to poetry’s same/except end-rhyme, Roni Horn’s faces, and Andy Warhol’s cans.

I have suggested that artists exploit repetition to introduce pleasure into their works. One might ask: Why is repetition bound to pleasure? The answer begins with the observation that Homo sapiens is not the only creature equipped to make same/except judgments. Even bees do it. This smacks of evolution.

In 1968, the social pychologist Robert Zajonc wrote an article in which he described what he called the Mere Exposure phenomenon:

Mere repeated exposure of the individual to a stimulus object enhances the subject’s attitude toward it.

He saw repetition as a kind of safe environment sensor, something that is essential for a creature driven to live within a cohesive social organization. So long as it keeps firing the environment is labeled “safe.” The glue that makes the label stick is the sense of pleasure it bestows. This place feels good.

As long as our surroundings register sameness, the odds for survival are in our favor.

Zajonc references work that points to infants going from fear to interest as a sound, frightening on first hearing, becomes a matter of interest upon repetition. The idea is that we all come with our own hard-wired self-monitoring baby monitor. As long as our surroundings register sameness, the odds for survival are in our favor. But as soon as a big enough difference is spotted, an internal version of a warning light begins to flash, “Be Careful. Something might be gaining on you.”

So, what has all this got to do with repetition in the arts? I think everything. I think artists repurposed this survival mechanism for their own ends: to ensure that their works elicited pleasure.

Think of it as borrowing from Peter to please Paul.

Samuel Jay Keyser is a theoretical linguist. He is Peter de Florez Emeritus Professor of the Linguistics and Philosophy faculty, and former Associate Provost at MIT. He has authored numerous books, including “The Mental Life of Modernism” and “Play It Again, Sam,” and is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Linguistic Inquiry.