Of Maritime Quarantines, the Third Plague Pandemic, and Hygienic Utopia

In 1901, the S.S. Sénégal, a ship famous for transporting spectators to the first Olympic Games in Athens, made international news. A leisurely cruise, organized by a leading French scientific journal, suddenly took a turn for the worse when it was discovered that a member of the crew had plague. All 174 passengers — including the future President of France, Raymond Poincaré, and film pioneer Léon Gaumont — were isolated in a lazaretto, a quarantine station for maritime travelers, off the Mediterranean coast of France.

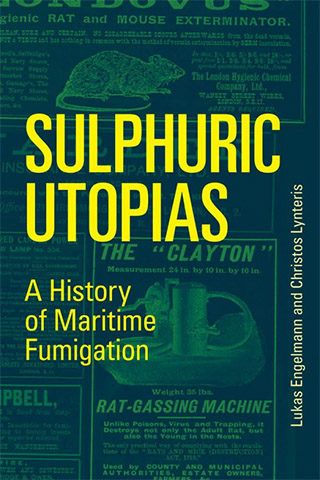

The scandalous event made headlines and galvanized medical opinion regarding the question of the role of the rat in the propagation of plague. Just as importantly, say Lukas Engelmann and Christos Lynteris, the co-authors of “Sulphuric Utopias,” it underscored an ongoing battle between two main principles of disease prevention: fumigation as a cure for both the human body and its environment and quarantine as a barrier method.

We asked Engelmann and Lynteris to tell us more about the significance of this event and its relevance to our current crisis, as well as shed light on the sanitary debates of the 19th century, when the concept of quarantine was pitted against the interests of economy, imperial trade, and emerging global markets. Our exchange is featured below.

The Editors: It was while researching the third plague pandemic that you decided to write “Sulphuric Utopias.” Can you tell us more about that research project? What made that pandemic different from those that followed, including the one we’re currently facing?

The Authors: Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic was a project funded by the European Research Council and based at the University of Cambridge and the University of St Andrews. The project examined the photographic record of the third plague pandemic, which erupted in Hong Kong in 1894 and quickly spread across all inhabited continents, leading to 12 million deaths. This was the first time an epidemic or outbreak was photographed and the project examined how this led to the emergence of epidemic photography as a distinct visual genre and practice. This was a genre distinct from medical photography in that it did not focus on the clinical image of the disease, but sought to establish and demonstrate its transmission pathways, natural reservoirs, social and environmental drivers, as well as the efficiency of a number of epidemic-control practices.

This was the first time an epidemic or outbreak was photographed and the project examined how this led to the emergence of epidemic photography as a distinct visual genre and practice.

The project has shown the importance of epidemic photography in the establishment of modern epidemiology, and in the emergence and development of the notion of the “pandemic,” which was first systematically employed in the context of the third plague pandemic. Even the smallest local outbreak assumed global proportions as it was seen and visualized both as part of the pandemic, and as the potential origin of an even greater pandemic wave, equivalent to the Black Death. This, as well as the fact that this was the first pandemic to be photographed and to be bacteriologically understood, marked the third plague pandemic apart from previous epidemics. The third plague pandemic has left a pervasive legacy, which is often forgotten by those who mistakenly set the origins of modern epidemiology and epidemic control at the 1918 influenza pandemic. It set some of the most persistent foundations of epidemiological reasoning and epidemic control while also defining the way in which pandemics are imagined into the 21st century. To give but one striking example, India’s Covid-19 legislation is no other than the 1897 plague emergency legislation, developed and deployed against the third pandemic.

The Editors: Chapter one examines quarantine, with its roots in the history of the Black Death, as a cause of concern in the sanitary debates of the 19th century. Who was involved in those debates, and what exactly were they debating?

The Authors: In that chapter, we sought to provide a deeper historical background on the two main principles of disease prevention that collide in the late 19th century: fumigation as a cure for both the human body and its environment and quarantine as a barrier method. First, we look at how the use of sulphur for preventative and therapeutic purposes has a history far beyond modernity. In the world of Paracelsian iatrochemical medicine, a branch of medicine based on the theories of the 14th-century physician Paracelsus that provides chemical solutions to diseases, sulphur had a fixed place as a therapeutic substance. The French physician J. C. Gales, for example, developed a fumigation box for patients to be cured of scabies with sulphuric fumes in 1822. We were in particular interested in tracing how this practice was later integrated into ideas of purifying air, cleansing the environment and to act on non-specific pathogenic qualities, which are sometimes referred to as miasma.

Quarantine, as many historians have shown, is in the 19th century deeply connected to the distribution of cholera. The effectiveness and indeed the very sense of quarantine, however, came under a lot of scrutiny. This was partly motivated by conflicting theories about how cholera is distributed. Those believing in the contagious nature of the disease were usually in favor of quarantine, while those adamant to defend cholera as a disease that emanates from the ground were eager opponents of what they described as an outdated and increasingly blunt method. Often, in Europe as well as in the Southern U.S., the latter group found itself well aligned with trade interests.

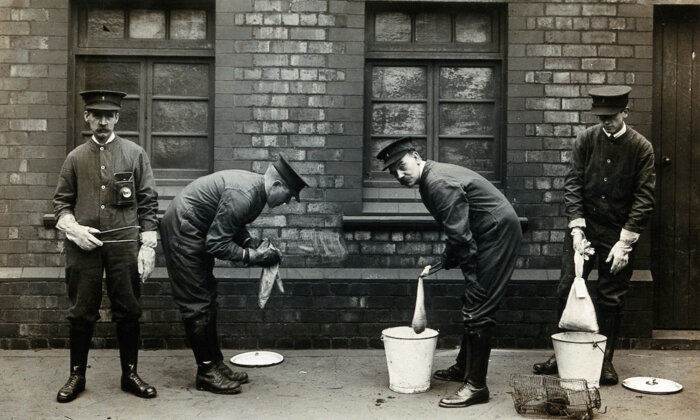

Instead of pitting economy against quarantine, the inventors of fumigation machines sought to abolish the costly practice of quarantine with an apparatus to keep vessels clean and to destroy bacteria, insects, and rodents instantly.

In the later 19th century, the concept of quarantine was basically pitted against the interests of economy, imperial trade, and emerging global markets — a motive that obviously continues to influence global health politics as in the case of Covid-19. The book’s argument begins then with the proposal of a resolution to this conflict in the 1880s. Instead of pitting economy against quarantine, the inventors of fumigation machines sought to abolish the costly practice of quarantine with an apparatus to keep vessels clean and to destroy bacteria, insects, and rodents instantly. The technology was supposed to protect global trade, to safeguard the economy while reliably securing the powerful empires from diseases emerging in the colonies: That’s what we call a sulphuric utopia.

The Editors: There’s a section in the book on what you call the Sénégal incident, a cruise-ship crisis from the early 1900s. The ship had been previously used to transport spectators to the first Olympic Games in Athens, had been in the course of a leisurely cruise when a plague case was discovered in a member of the crew. What’s the significance of this incident, and is it at all relevant to our current crisis?

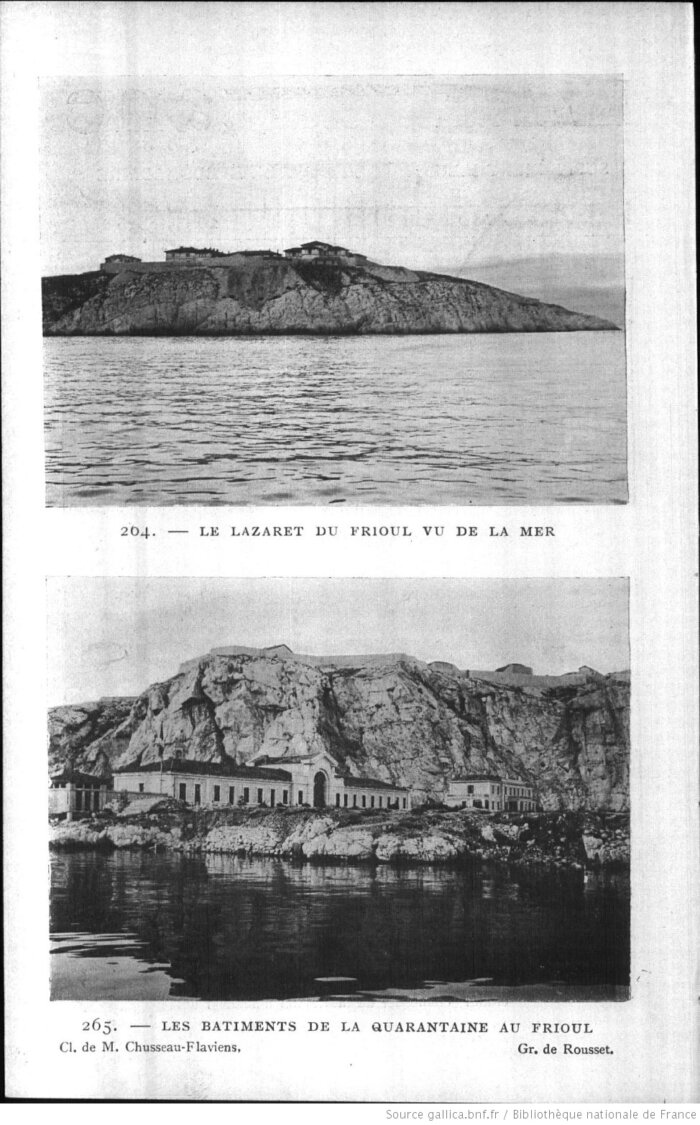

The Authors: The crisis on the S.S. Sénégal was a sensation at the time, not unlike the recent incident of the Diamond Princess. The boat was famous, as it had been used to transport spectators to the first Olympic Games in Athens, and the passengers who became caught up in the 1901 quarantine included leading politicians and celebrities, like the future PM and President of France Raymond Poincaré and the film pioneer Léon Gaumont. When it was discovered on September 16, 1901, that a member of the crew had plague, the boat had to return to Marseille where it was subjected to quarantine in the Frioul lazaretto, a quarantine station for maritime travelers; this made international news.

Over the 10 days of their confinement, the passengers did not seem to be having a bad time at all, with the press at the time featuring photo-reportages of their time in quarantine. They held galas, improvised poems about rats, Gaumont took some marvelous photos, and the architect-poet Jean Bertot even published a diary of his experience of the whole affair.

However, the incident also had a significant effect on maritime sanitation, as it galvanized public opinion on the role of the rat in the propagation of plague. The idea that rats transmitted the dreaded disease, via their fleas, was not new — it had first been established by the Pasteurian doctor Paul-Louis Simond in 1898. However, whereas the third plague pandemic had until then been a colonial problem for France, the Sénégal incident brought the pandemic and its vector home as it were. Doctors as well as the lay public demanded to know if rats hiding in the holds of boats arriving from infected harbors could spread the disease to France, and whether they could even establish plague reservoirs in French harbors. It also led to questions of responsibility and blame: Who should be keeping French ports safe? Navigation companies or port authorities? And above all, it raised questions regarding the best means of deratization. In the book we examine how this fostered ideas and methods of maritime fumigation as an essential part of the defense of Europe against plague.

Lazarettos conjure up a bleak image today, but in reality by the early 20th century they bore little resemblance to the bare-wall sanitary prisons we usually associate with this name.

Coming back to the question of cruise-ships, the Covid-19 crisis unexpectedly offers an illumination of the fact that we lack a vital infrastructure which nobody thought we needed any more: the lazaretto. Lazarettos conjure up a bleak image today, but in reality by the early 20th century they bore little resemblance to the bare-wall sanitary prisons we usually associate with this name. Across the globe, quarantine stations for passengers and ship crews had developed sophisticated systems of separation between infected individuals and contacts, as well as of disinfection, both for passengers and crew and their belongings. Today these stations have been either completely abandoned or transformed to hotels, tourist sites, or in some cases prisons. Could Covid-19 lead to a resumption or re-invention of maritime lazarettos? If key ports possessed modern quarantine stations, led by scientific principles and offering healthcare, comfort, and rights of those confined in them, these could be far superior alternatives to letting people in limbo in infected cruise-ships as we have recently seen in the case of the Zaandam, the Diamond Princess, and others.

Lukas Engelmann is Chancellor’s Fellow in History and Sociology of Biomedicine at the University of Edinburgh.

Christos Lynteris is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of St Andrews. Lyntseris and Engelmann are the the co-authors of “Sulphuric Utopias: A History of Maritime Fumigation“